One of French President François Hollande’s major policy pillars is a reform of the French educational system, with both an overhaul of its organisational structure and the promised creation of 60,000 jobs in a sector in crisis from an annually increasing shortfall of teaching staff.

Beginning earlier this summer, education minister Vincent Peillon has established a programme of nationwide consultative talks, aimed at defining “the school of tomorrow”, with representatives of all parties concerned, from teaching staff and management to pupils’ and parents’ committees. The government hopes to reach a consensus by October on reforms that are due to be put before parliament later this autumn.

The debates were provided with more food for thought this week with the publication of the latest annual international survey of educational systems conducted by the Paris-based Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). The 570-page study is a comparison of the state and performance of educational systems among the OECD’s 34 member countries and also Argentina, Brazil, China, India, Indonesia, Russia, Saudi Arabia and South Africa. Called ‘Education at a glance 2012: OECD indicators’, it contains a number of findings that underline important structural failings in the French education system despite the fact that it benefits from above-average funding.

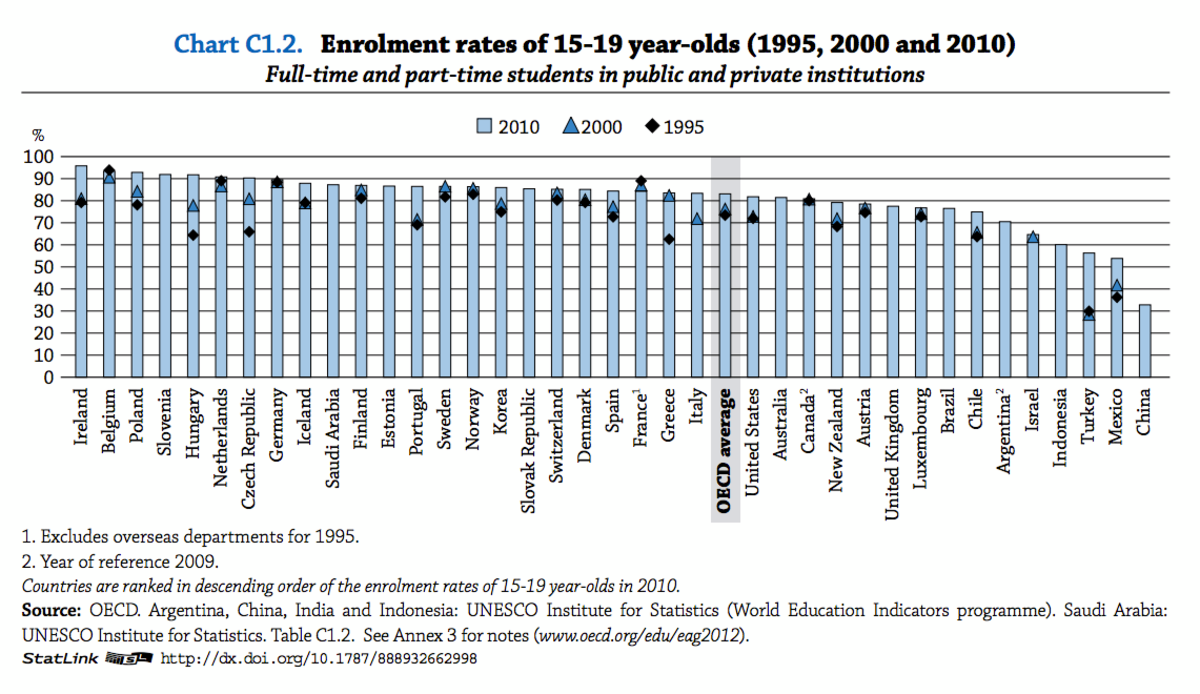

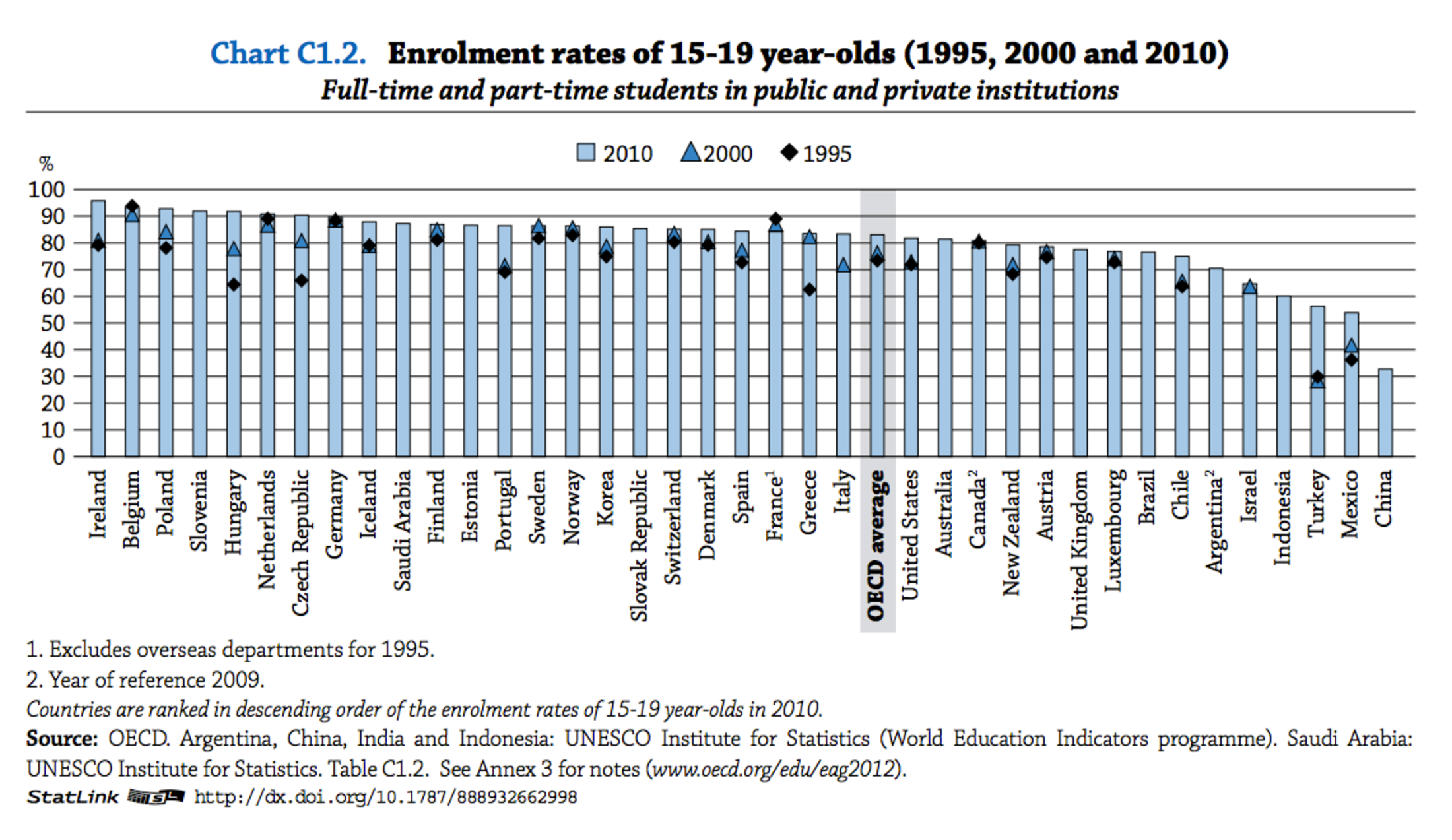

The most significant is the recorded fall in the numbers of 15-19 year-olds enrolled in full-time education and which the OECD described as “preoccupying”. Between 1995 and 2010, the percentage of this age group attending school in France dropped from 89% to 84%.

While the numbers enrolled in 2010 were just above the OECD average (83%), the downward trend in France went counter to what was in fact an overall increase of 10.4% in the numbers of 15-19 year-olds in full-time education among all member countries (see chart below). Furthermore, the 2010 figure of 84% had remained the same since 2008.

Despite this, France spends more per secondary school pupil per year, at 10,696 dollars, than the OECD average of 9,312 dollars, while the proportion of its Gross Domestic Product (GDP) spent on education (6.3% of GDP) is also more than the OECD average (6.2% of GDP).

Enlargement : Illustration 1

OECD education analyst Éric Charbonnier, who presented the report to the French media this week, said the results should be considered alongside those of the OECD’s Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA) 2009 study of the numbers of pupils failing in their studies. In France, the numbers of pupils in difficulty who retake school years and re-sit exams is falling, and some 150,000 leave secondary education every year without any form of diploma. “The system is degrading at the bottom,” Charbonnier commented.

The OECD also found that those who leave school early, either without any diplomas or with minimal qualifications, fair worse on the labour market in France compared to the average results across OECD countries. Among the 15-19 year-old age group no longer enrolled at school, in France 71% are registered as unemployed or have no professional activity, compared with an OECD average of 57%. Among 20-24 year-olds who left school before studying for the school cycle final exams (e.g. the baccalauréat), 25% are unemployed in France compared with an OECD average of 16%.

The report added to the growing debate in France over the need to reorganize school working time, notably for the more than two-month summer holidays to be reduced. France has the shortest school year of any in the OECD, with an official 36 weeks but which is in practice, after deducting the number of bank holidays contained within it, just 35 weeks. Despite this, France has a higher than OECD average number of annual class hours worked (French 7-8 year-olds have 847 hours of classes per year, against an OECD average of 774), producing a dense timetable but which has not produced correspondingly superior educational results. The study pointed out that a shorter school year provided less opportunity to assist pupils in difficulty with their studies.

The report also found that France has a lower number of over 25 year-olds enrolled in higher education than the OECD average. While 4% of 25-29 year-olds are in full time education in France, they number 16% across all OECD countries. France invested significantly more than the OECD average in higher education between 200 and 2009 (a funding increase of 19% in France compared to an OECD average of 15%), and spends an average 14,642 dollars per higher education student per year compared to 13,728 dollars across the OECD. But the numbers of those who obtained a doctorate or PhD across the OECD member states in 2010 was just below the average of all member states, and notably less than in Austria, China, Germany, Finland, Slovakia, the United Kingdom, Sweden and Switzerland.

Meanwhile, France came in first place among OECD countries for the number of 3-4 year-olds enrolled in education, with a score of 100%, just ahead of the Netherlands, while the OECD average is 79%. Teachers in this category in France have an average class of more than 20 infants, compared with an OECD average of 14, and primary school classes per teacher number number an average 18.7 pupils against an OECD average of 15.8. “It’s the quality of the teachers that count more than the size of the class,” cautioned Charbonnier.

Finally, the study found that French primary and secondary school teachers are both younger and earn lower basic salaries (excluding bonuses and overtime) than the OECD average. However, maximum salaries in both categories, obtained after more than 15 years' service, are higher than the average.

-------------------------

English version: Graham Tearse