Four years after investigations ended, and a year after prosecutors called for the case to be dropped, a French investigating judge has unexpectedly decided to reopen the probe into the massacre at Bisesero in Rwanda in June 1994, according to Mediapart's information. This bloody event is widely seen as being one of the most embarrassing episodes for France during the genocide that was carried out against the Tutsi people.

On June 3rd the judge, Michel Raffray, informed the parties involved that he felt it necessary to “continue the investigation”, following the report by an independent commission on the Rwandan genocide that was presented to President Emmanuel Macron in March 2021. The commission was chaired by historian Vincent Duclert.

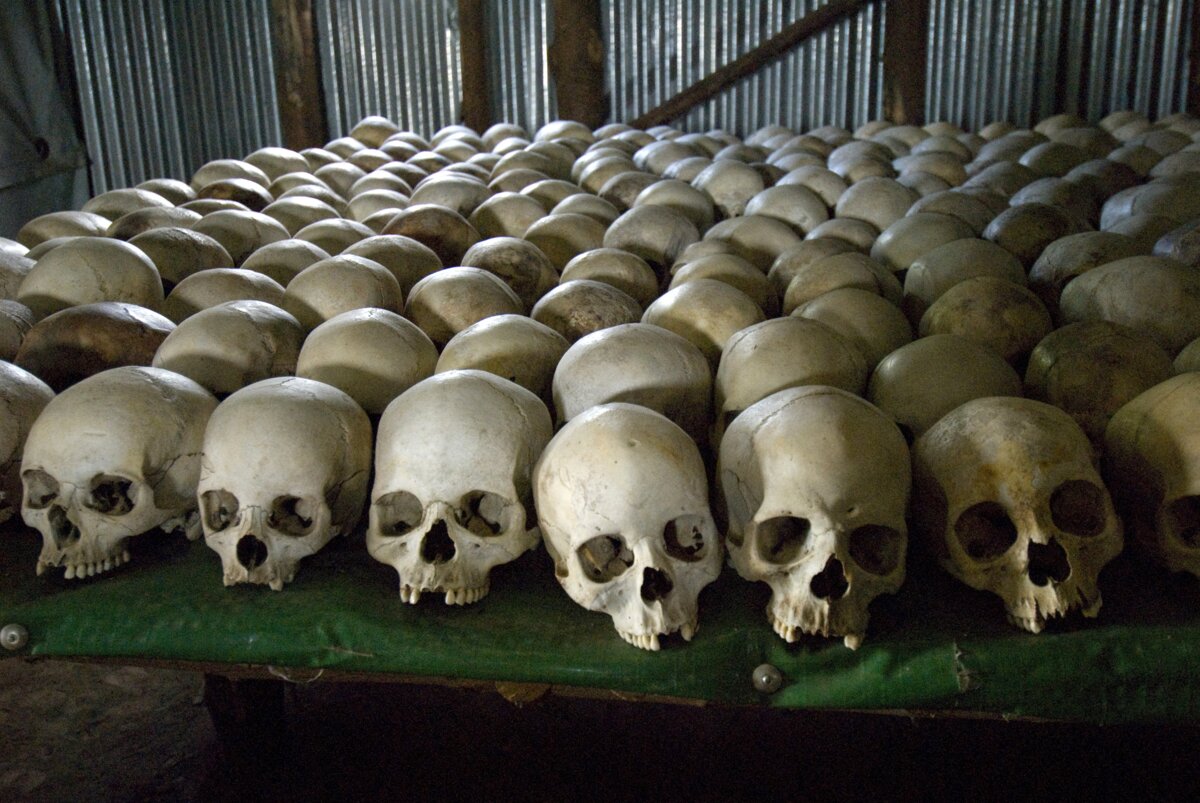

Enlargement : Illustration 1

The Duclert Commission had unprecedented access to official archives and concluded that France bore “serious and overwhelming responsibilities” in relation to the 1994 genocide against the Tutsis in Rwanda which left between 800,000 and a million people dead. At the same time it also said that there was “nothing in the archives that were examined” to show the French state's complicity in events “if by this we mean a willingness to join a genocidal operation...”

Around a thousand Tutsi civilians perished in the Bisesero massacre of late June 1994, systemically murdered by Hutu government troops and militia, and the grim episode is dealt with at length in the Duclert report.

There is a before and after Bisesero.

For more than 20 years there have been two opposing versions of events at Bisesero, which were argued out first in the press and then inside judges' chambers after legal proceedings were triggered at the demand of several different civil parties; Rwandan survivor groups, non-governmental organisations and various associations. These include the International League against Racism and Anti-Semitism (LICRA), the International Federation for Human Rights, the Human Rights League, the anti-corruption body Survie and the Rwandan survivors group IBUKA.

On one side there are at least three soldiers from France's United Nations-mandated military mission in Rwanda at the time, Operation Turquoise, as well as several journalist who were present, who insist that the French army general staff were fully aware of what was happening and let the massacre take place. It is claimed they declined to intervene despite alerts that had been given. On the other side, the military top brass insist that they only belatedly discovered what was going on and then provided immediate help to those who escaped the carnage, as they were mandated to do by the UN.

A tricky legal debate

Does the inaction of which the army is accused amount to evidence that it participated in genocide by abstention? It is a tricky legal issue. The judges involved placed five officers from Operation Turquoise, including its commanding officer General Jean-Claude Lafourcade and the head of special operations, Colonel Jacques Rosier, under the status of 'assisted witnesses' in relation to allegations of “complicity in genocide” and “complicity in crimes against humanity”. In other words, the judges considered them to be involved in events relating to the alleged crimes but not sufficiently involved for them to be placed under formal investigation.

Given that no one was placed under formal investigation it had been widely assumed that the probe would end with the judge agreeing that the case be dropped, following calls from prosecutors along similar lines. But then came the Duclert report. The judge commissioned a specialist at the 'crimes against humanity' unit in the Paris court system to write a summary of that report. This was delivered on June 23rd.

That summary quotes the Duclert Commission conclusion that “the findings of political responsibility [editor's note, for the genocide against the Tutsis] introduce institutional responsibility, both civilian and military”. The commission had found evidence of “irregular administrative practices, parallel chains of communication and even command, circumvention of the rules of engagement and legal procedures, acts of intimidation...”

Concerning the Bisesero massacre itself, the Duclert Commission stated that “in the face of the objective of saving the victims of the massacres, Bisesero is both a failure and a tragedy. Even though the collective awareness of the French commanders was gradual, Bisesero was a turning point in the awareness of the genocide. There is a before and after Bisesero.”

In their summary, the Paris courts' specialist in crimes against humanity also pointed out that the commission had highlighted an episode in which soldiers from French special forces, filmed by an army video team, had met a survivor of the Bisesero massacre. In the film these soldiers had shown “very little psychology or even empathy towards a man who is visibly in shock, who has just experienced days of 'manhunt'”.

The Duclert Commission report had continued: “...These elite soldiers seem to give little credence to his testimony, particularly on the responsibility of the Hutu authorities in the genocidal massacres whose effects on the civilian population they have just witnessed first hand.”

The summary report also mentioned another video filmed by the army, whose existence remained unknown to the public until it was revealed by Mediapart in 2018. In this footage Colonel Rosier, head of the special forces unit, is shown to be utterly indifferent to the report from one of his subordinates about the Bisesero massacre and its awful human tragedy.

When Colonel Rosier was questioned about this video in 2015 he told the judges: “...Looking at this scene and knowing myself, I see that I don't catch on, for in all likelihood I don't grasp what he's telling me, my mind is elsewhere, I'm in the process of preparing for my press briefing, lots of things have happened since the day before. You have to understand that I was under pressure. It's true that, seeing this scene again, it seems unbelievable to me that I didn't react to the information.”

There is no indication at this stage that the reopening of the case is the prelude to accusations being made against military personnel in relation to the Bisesero massacre. But for several of the civil parties involved in the case the move justifies a deeper probe into the “centre of power at the time”.

For example, Éric Plouvier, lawyer for the Survie association, believes that the investigation should now extend to the questioning of General Christian Quesnot, who at the time was President François Mitterrand's military chief of staff and who was a dogged supporter of the Hutu government. He also believes that Mitterrand's former chief of staff at the time, Hubert Védrine, should also be questioned.

-------------------------

If you have information of public interest you would like to pass on to Mediapart for investigation you can contact us at this email address: enquete@mediapart.fr. If you wish to send us documents for our scrutiny via our highly secure platform please go to https://www.frenchleaks.fr/ which is presented in both English and French.

-------------------------

- The original French version of this report can be found here.

English version by Michael Streeter