Former four-star French army general Jean Varret, 84, whose career spanned more than three decades in France’s armed forces, has for the first time agreed to give his account of the political and military “faults” committed by France in the run-up to the 1994 genocide in Rwanda of mostly Tutsi victims, directed by the Hutu regime in place.

Over a period of 100 days, from April to July 1994, almost one million people – about a tenth of the Rwandan population – were slaughtered in massacres that erupted after several years of civil war between rebels from the minority Tutsi ethnic population and the Hutu regime that was propped up by France.

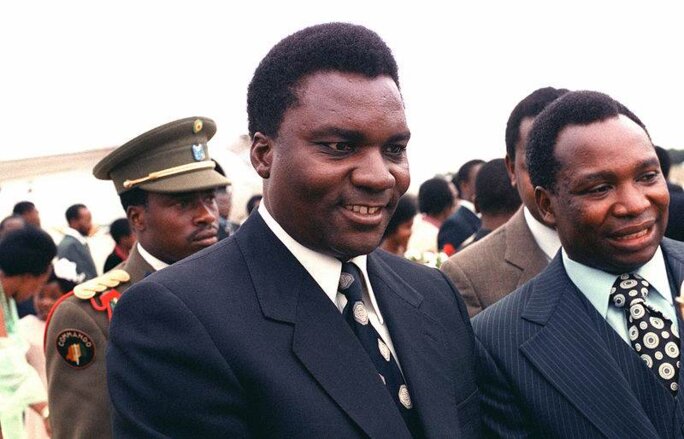

The genocide began after Rwanda’s Hutu president Juvénal Habyarimana was assassinated in a missile attack on his plane on April 6th 1994. The country had been plunged into a civil war beginning in 1990, when the Tutsi-led Rwandan Patriotic Front invaded Rwanda from neighbouring Uganda seeking the overthrow of the Hutsi regime. While a peace agreement was eventually brokered in 1993, the killing of Habyarimana – whose assassins are still not identified – immediately sparked the slaughter.

In the intervening years, France had provided military protection for the Hutu regime, which was officially a cooperation and assistance mission that did not involve direct participation in the conflict. But over the past 25 years, mysteries remain about the true role of Paris in supporting the regime, and its part of responsibility in the horrific events of 1994.

For General Varret, the most senior French army officer to finally speak out about the events in an interview with Mediapart and public broadcaster Radio France, there had been numerous indications of the looming tragedy.

Enlargement : Illustration 1

Varret believes senior officials in the French army and also the presidential office, the Élysée Palace, under the late French socialist president François Mitterrand, were “blinded” by the extremist elements in the then-Rwandan regime. Now, a quarter of a century after those events, the general says the “fault” committed by the upper echelons of both institutions “led to a genocide”.

For Varret, the first warning of the horror to come was in November 1990, when Varret was in the Rwandan capital Kigali after his recent appointment as head of France’s Military Cooperation Mission. One month earlier, the Tutsi rebels of the Rwandan Patriotic Front had reached the outskirts of the capital, and the ruling Hutu regime was facing collapse. While it was temporarily protected by two French parachute units sent on the orders of the Élysée, the senior officers of the Rwandan regime’s armed forces, the FAR, were well aware of their weak position.

At a meeting that November with his Rwandan military counterparts, Varret was handed what they called a “shopping list”. Colonel Pierre-Célestin Rwagafilita, head of the Rwandan gendarmerie, requested the supply of machine guns and mortars to maintain order. Varret refused. “In face of my clear refusal, the head of the gendarmerie announced [editor’s note: to those present] ‘Gentlemen, you can leave, I will remain with the general’,” recalled Varret (see video interview immediately below). “And then he told me, ‘We’re in private conversation, we’ll speak clearly, between military men. I ask you for these weapons because I am going to take part with the army in the elimination of the problem. The problem is very simple: the Tutsis are not very many, we are going to eliminate them’.”

Thus it was that, four years before the genocide, a Rwandan officer explicitly announced the regime’s murderous intentions. It was all the more significant in that Pierre-Célestin Rwagafilita was part of the inner circle of then-Rwandan president Célestin Rwagafilita’s close entourage.

On his return to Paris, Varret gave a blunt account of the risk for the civilian population in supporting a regime that appeared obsessed by the threat of a Tutsi ‘fifth column’. His reports were circulated within the defence ministry, and also that of overseas cooperation but, he says, while they were read they were not listened to, notably by those “who occupy key posts”. Varrey personally knew the military chiefs who surrounded the French president, namely General Christian Quesnot, Mitterrand’s military chief-of-staff, his deputy, Colonel Jean-Pierre Huchon, and Admiral Jacques Lanxade, head of the French armed forces.

Varret, a cavalry officer who had been trained at France’s top military academy, Saint-Cyr, knew that he was up against a highly influential group within the armed forces, the marine troops (formerly the ‘colonial troops’), who were commandingly present in overseas operations, and in Africa in particular. Its senior ranks had resented Varret’s appointment as head of the Military Cooperation Mission, which they regarded as their own exclusive preserve. Furthermore, within this inner sanctum nobody was willing to question the opinion of the French president.

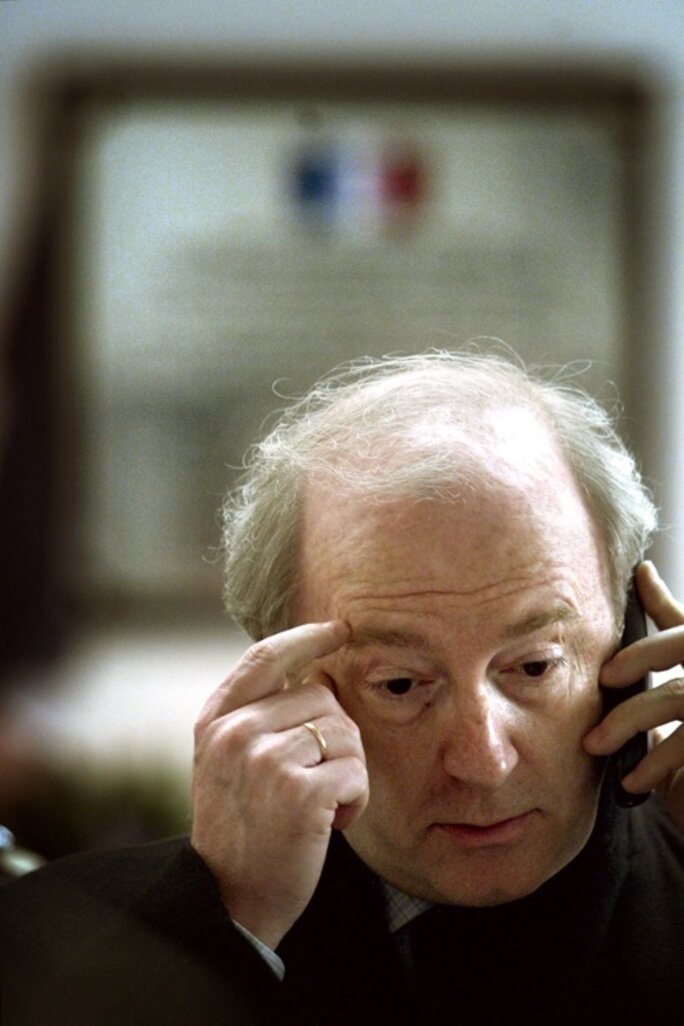

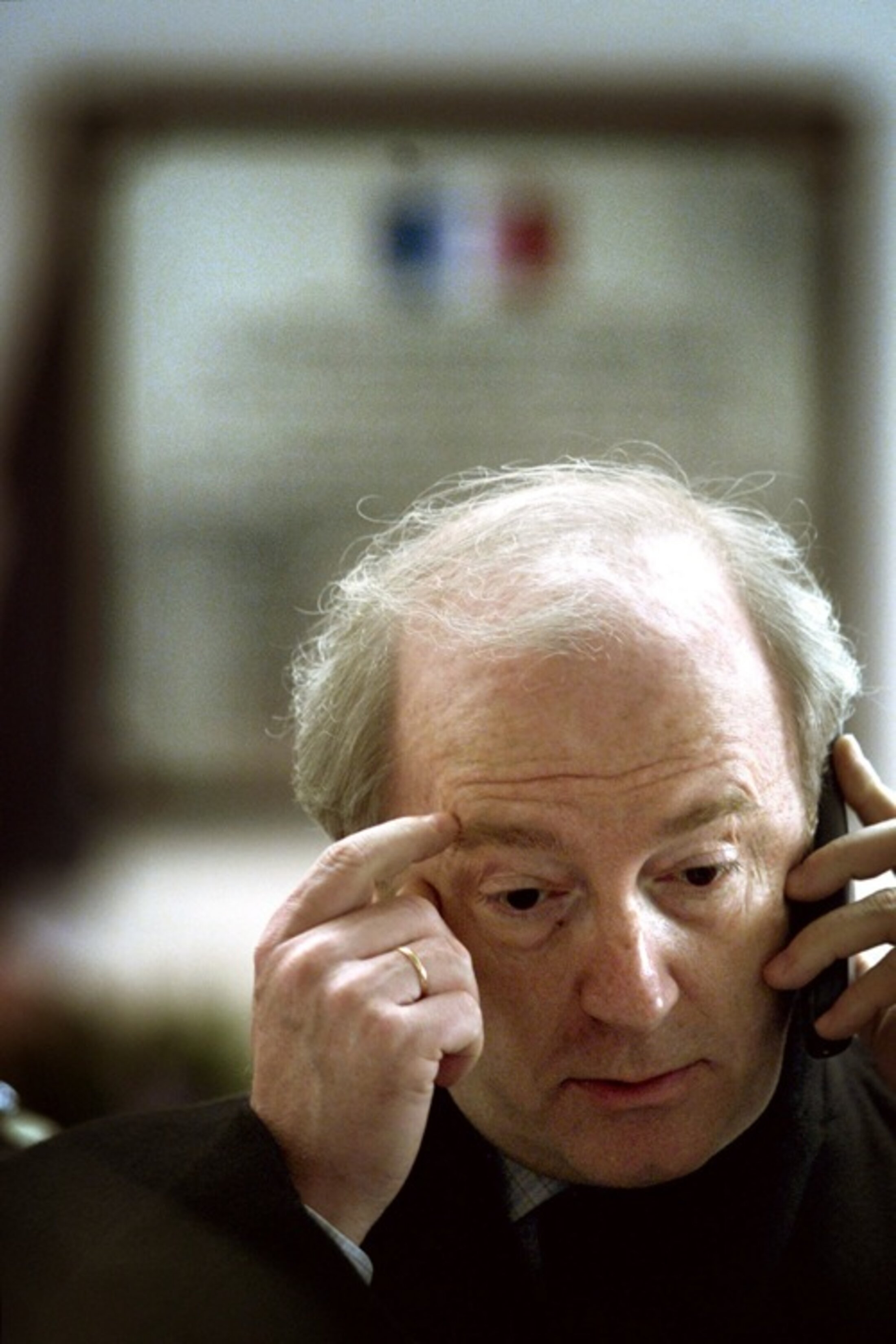

Varret’s serious allegations are refuted by Admiral Jacques Lanxade, who was interviewed at length by Mediapart as part of this investigation. Lanxade was very close to Mitterrand, who he served as the president’s personal military chief of staff, from 1989 to 1991, and from 1991 to 1995 as head of the French armed forces. Lanxade’s version of the events centres on the political choice made by Mitterrand as of the beginning of the crisis, in October 1990. “Our role was to ensure that this did not happen,” he told Mediapart, referring to the genocide. “We did not want a destabilisation of Rwanda. So we did three things: a political approach to [president] Habyarimana so that he accepted a democratisation of his country, which he began to do. Then we negotiated and we were very involved in the [August 1993] Arusha Peace Agreement [between the Rwandan regime and the Rwanda Patriotic Front (FPR)]. We also gave support to the regular army of the country to keep out the FPR and so that destabilisation wouldn’t happen.”

“When information like that of Jean Varret arrived, well, it justifies our presence,” Lanxade continued. “Varret was right to say what he did, but one cannot draw from this the conclusion that we had been imprudent.” For Lanxade, the alert by Varret actually showed Mitterrand’s politicy choices were correct. “But what could we do at that moment?” he asked. “We weren’t going to pull out. We were precisely there to prevent what Varret thought was a possible eventuality, through technical cooperation with the gendarmerie, with the Rwandan armed forces. Our intervention was aimed at avoiding the fall of the government and civil war. What should we have done? Leave? But in that case it was immediate civil war.”

Over time, two groups of opinion were to become established on the French side; the ‘doves’, who tried to sound the alarm over the excesses in the Élysée’s strategy, and the ‘hawks’ who, at every new offensive by the FPR, urged for further support to be given to the Rwandan regime’s army. The effect was a hardening of extremist elements among the Rwandan political class.

Meanwhile, the then French defence minister (1991-1993), Pierre Joxe, was one of the first senior French politicians to warn François Mitterrand of the dangers in offering too strong support to the Habyarimana regime. In a note he sent to the French president dated February 26th 1993, Joxe warned: “The only means of pressure of some strength that is left for us – given that direct intervention is excluded – seems to me to be [raising] the possibility of our disengagement.” Questioned in 2014, Joxe’s former deputy ministerial chief of staff, Louis Gauthier, said: “Pierre Joxe had quite marked reservations about the Élysée’s Africa desk, and towards General Quesnot. There was a parallel cell with which Joxe intended breaking off relations.”

'When a military figure touches politics, they are in the wrong'

Following the victory of the Right in parliamentary majority in elections in France in March 1993, when the socialist Mitterrand was forced to share power with a conservative government, the ‘doves’ gained the upper hand with prime minister Édouard Balladur, He tried to limit the extent of French intervention in Rwanda, but he failed to win every battle over this with Mitterrand. Under the French constitution, the president is the ultimate chief of the armed forces, and Mitterrand exerted this prerogative amid the strongly opposing arguments expressed in the special defence committee meetings.

There was a similar division among the intelligence services, where one of the principal changes wanted by Pierre Joxe paradoxically reinforced the position of the ‘hawks’. Joxe, drawing on the lesson of the intelligence failures during the first Gulf War (August 1990-January 1991), created two new military structures in June 1992. One was the Special Operations Command (COS) which was to regroup into one unit the special forces from all branches of the military, while the other was the Military Intelligence Directorate (DRM) which was to be the eyes and ears of the armed forces chiefs of staff, again bringing together the relevant staff from all sections of the armed forces.

The DRM drew on information from French troops deployed in Rwanda in the framework of the military cooperation mission, and who would take a very similar view of events as those of the officers in the mission, and who largely supported the extremist position of the Habyarimana regime. Meanwhile, the French foreign intelligence services, the DGSE, noted in its reports the dangers of a radicalisation of the Rwanda conflict.

The second warning received by General Jean Varret came at the beginning of 1993, a period that marked a turning point in French policy – which would irremediably adopt a hardline approach. Once again, there was another turn of the wheel in the mechanics that would lead to the genocide. At the beginning of January 1993, a commission of inquiry sent to Rwanda by the International Federation for Human Rights (FIDH) had collected evidence of massacres of ethnic groups committed over previous months. After the commission members had left the country, further mass murders were committed by followers of the extremist Hutu Power supremacist movement which was close to the MRND, the party of president Habyarimana, when about 300 Tutsi were killed in northern Rwanda.

Enlargement : Illustration 3

In reaction, the Tutsi FPR launched attacks on February 8th 1993 against the northern towns of Ruhengeri and Byumba, both political fiefdoms of president Habyarimana, and subsequently continued south to within 30 kilometres of the capital Kigali. Around one million refugees from the fighting amassed around Kigali, trapped between the FPR and the army of the regime.

France reinforced its military positions, sending another detachment of troops, from the 1st marine infantry parachute regiment (1er RPIMa), led by Lieutenant Colonel Didier Tauzin, to bolster the Rwandan regime’s forces. Within 15 days, the Tutsi rebel advance was halted.

It was during this period that General Varret would discover he had been betrayed. “One day, in the Akagera [national] park [situated in north-east Rwanda, close to Tanzania], I inspected the military assistance and training detachment [DAMI] of the 1er RPIMa, which was under my orders,” he recalled. “And then, I discovered that they were involved in interventions that I did not allow, namely that they had been in Uganda, behind enemy lines, to try and collect intelligence on the FPR.” The incursion was a serious breach of orders that French troops were not to become directly involved in the conflict. “So, I learnt that,” continued Varret, “a piece of solid information, and I gave them a rocket. I returned to Paris and three days later I was given a message saying, ‘the DAMI units are no longer under your orders’.” Varret would never discover who was behind the move.

“I took that as a disavowal,” said Varret. “And I recently discussed the matter by phone with Admiral Lanxade, asking him ‘Why was I removed from command of the DAMI?’. His reply was, ‘We had just created the COS and the 1er RPIMa was placed under its orders’. So, it could well be that this lack of confidence was due to the fact that the COS had taken command of units, including those present in Rwanda.”

In April 1993, France’s overseas cooperation minister, Michel Roussin, newly appointed in France’s conservative government elected one month earlier, a former member of the DGSE, told Varret that he would not be re-assigned for another year as head of the Military Cooperation Mission. Had he just fallen victim to a ‘military lobby’ as he calls them? “The military lobby is a connivance between certain military figures, who did not represent a majority but who had key posts: the [president’s] military chief of staff, the DRM, the armed forces chiefs of staff,” said Varret. “This group, certain figures of which I knew, applied pressure, including to oust me from my responsibilities.”

Did these same military figures push France too far with its engagement in Rwanda? “I think so,” replied Varret. “Not the institution, but certain military figures in key posts went too far, because they didn’t want to take into account the dangers of this policy of support for Habyarimana. Effective support, meaning that there were necessarily breaches. The mission of the cooperation [programme] was to train, equip, but certainly not to take part in combat. And I think this military lobby was more inclined to help with combat.”

Jean Varret knows very well situations of high tension at the summit of institutions and political power. Graduating from the elite Saint-Cyr military academy in 1959, he began his career as an army officer during the war of independence in Algeria, where he served as a parachutist, a “red beret”, spending some two years in mountain combat against the Algerian pro-independence rebels of the National Liberation Front, the FLN. He was against the practice of torture used by the French military in the colony but, in the spring of 1961, he joined the camp of military putschists – high-ranking former French officers – who, opposed to president Charles de Gaulle’s moves to negotiate the abandoning France’s rule over Algeria, launched a failed coup on April 21st that year. “The putsch was stupid,” he says now. “From that unfortunate experience, I returned convinced that, as soon a military figure touches on politics, they are in the wrong. We are technicians, and we should not use our techniques, which are very special – that’s the law of war – to be used to the benefit of politicians. Putschs? Never again.”

Enlargement : Illustration 4

Varret’s account of France’s involvement in Rwanda has an undertone of a mute military putsch inside the state, in which the military took over the power from politicians. The question remains: why was Rwanda the object of such relentless political attention at the Élysée? Asked about this, Varret appeared to dodge the issue. “You’d have to be inside the head of the president and officials of the time,” he said.

At the forefront of the “officials” of the time was Hubert Védrine, secretary general of the Élysée from 1991 to 1995, and later French foreign minister (1997-2002). Vedrine’s post made him something of an information traffic controller, the man who filtered the reports handed to Mitterrand. Varret believes Védrine should be brought to account over the “political and military errors” that were committed regarding Rwanda.

Hubert Védrine did not reply to Mediapart’s request for an interview.

Removed from his job as head of the Military Cooperation Mission in the spring of 1993, Varret turned down the offer he was given by the Élysée to take up a comfortable, sidelined post, and left the army. With the benefit of hindsight, he regards this as a welcome event, for he would never have accepted a role of supporting what he calls “the military lobby” during the crisis that began on April 6th 1994, when president Habyarimana was killed in the missile attack on his Falcon jet as it approached Kigali.

Asked how he would sum up what was a French political fiasco over Rwanda, he said: “Unfortunately, history has proved that it was a fault, more than an error, because it led to a genocide.”

“There was, all the same, a blindness. That’s to say that no civilian or military figure would have wanted a genocide. None. But on the other hand, some didn’t take the danger seriously.”

That “danger” was so disregarded that the first move made by the French army after the shooting down of Habyarimana’s plane was to send a Transall military transport plane to Rwanda, which touched down at Kigali on April 9th 1994, full of weapons destined for the regime’s army. Officially, its mission was uniquely to evacuate European civilians trapped in the country.

-------------------------

If you have information of public interest you would like to pass on to Mediapart for investigation you can contact us at this email address: enquete@mediapart.fr. If you wish to send us documents for our scrutiny via our highly secure platform please go to https://www.frenchleaks.fr/ which is presented in both English and French.

------------------------------------------------------------------------------

David Servenay is an independent journalist regarded as a specialist of the history of the 1994 genocide in Rwanda, about which he has co-authored two books published in France by La Découverte: “Au nom de la France”, guerres secrètes au Rwanda (‘In the name of France’, secret wars in Rwanda, co-authored with Benoît Collombat) and Une guerre noire, enquête sur les origines du génocide rwandais 1959-1994 (A black war, investigation into the origins of the Rwandan genocide 1959-1994, co-authored with Gabriel Périès).

- The French version of this report can be found here.

English version by Graham Tearse