On May 8th 2002, in the Pakistani port city of Karachi, 11 French naval engineers were killed when a suicide bomber drove a car packed with explosives into the side of their minibus as they left their hotel. Three Pakistani nationals, including the bomber, also died in the attack which left 12 seriously wounded.

The engineers, employees of the French state-owned naval construction company DCN (now renamed as the DCNS), were in Karachi to help build one of three Agosta 90B submarines sold by France to Pakistan in a deal concluded eight years earlier.

The1994 deal and three other weapons sales contracts signed that year with Saudi Arabia are at the centre of a 13-year French judicial investigation into the engineers’ murders, and a scandal that has become known in France as ‘The Karachi Affair’.

Pakistani authorities blamed the suicide bomb attack as the work of terrorists affiliated to al-Qaeda, a theory publicly endorsed by the French authorities. However, after the appointment in 2007 of Judge Marc Trévidic as head of the French judicial investigation, evidence emerged suggesting that the Karachi killings were carried out in revenge for France’s non-payment of massive secret commissions promised to intermediaries involved in the contract with Pakistan.

Trévidic’s investigations subsequently uncovered evidence of a vast illegal political funding scam in France in which millions of euros were siphoned off from secret kickbacks paid in the deals, and which were rerouted to France for illegal political funding, called retro-commissions. That evidence led to the opening in 2010 of a separate and parallel judicial investigation specifically centred on the illegal retro-commissions.

It found that the proceeds of these, mostly carried in suitcases to France from Swiss banking centre Geneva, was apparently destined to fund the 1995 presidential election campaign of conservative politician Édouard Balladur, who mounted his bid while prime minister, and whose campaign spokesman was his then budget minister, later French president, Nicolas Sarkozy.

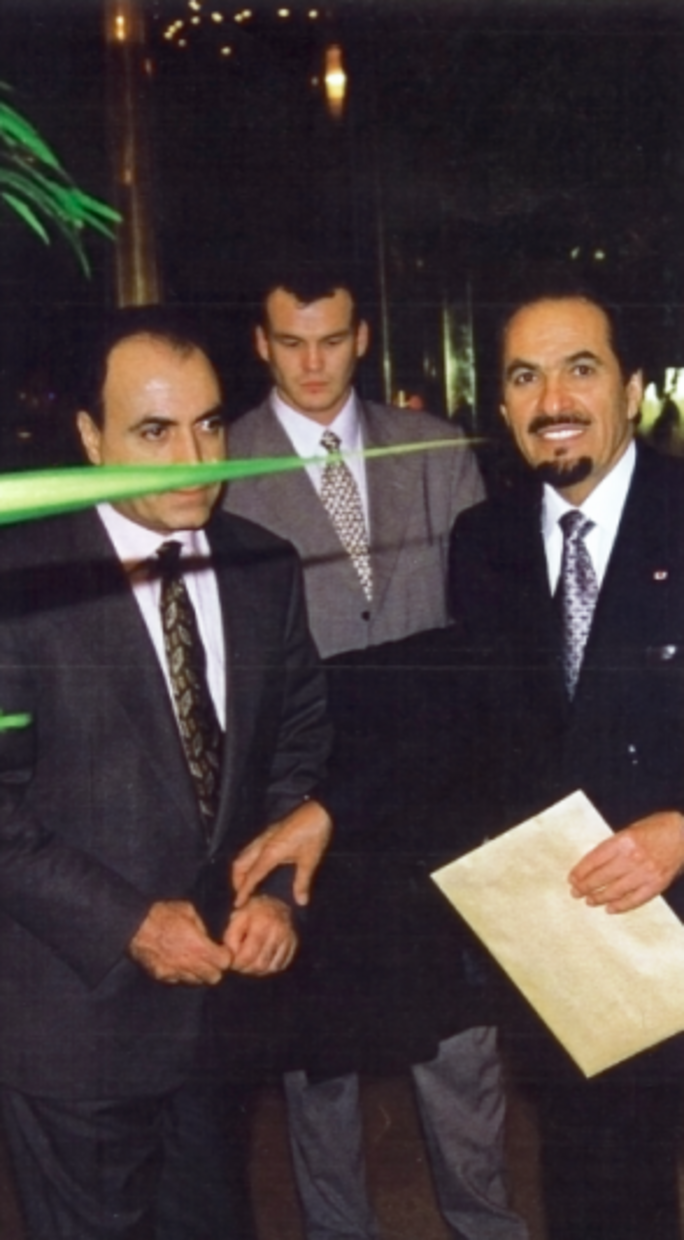

Enlargement : Illustration 1

That investigation was concluded last year when six men were sent for trial, which is to open later this year, on charges relating to the alleged scam. Three of these served as top aides in Balladur’s 1993-1995 government: Nicolas Bazire, who was Balladur’s chief-of-staff and who is now managing director of French luxury goods firm LVMH; Renaud Donnedieu de Vabres, who served as a special advisor to Balladur’s defence minister and who later became culture minister between 2004-2007, and Thierry Gaubert, 63, who served as joint chief-of-staff for Balladur’s budget minister Nicolas Sarkozy.

Also accused are Paris-based arms dealer and businessman Ziad Takieddine, arms dealer Abdul Rahman El Assir and Dominique Castellan, the former head of the DCN’s international sales division.

Balladur mounted his 1995 presidential bid as a rival to the designated candidate of the conservative RPR party (which later became the UMP), Jacques Chirac, who finally won the election. The evidence uncovered in the investigation indicates that the Balladur government imposed intermediaries on the 1994 contracts with Saudi Arabia and Pakistan, siphoning off secret commissions paid to them for the funding of Balladur’s intended, but then still unannounced, bid for the presidency.

Even though France was already assured of winning the contracts, the intermediaries Takieddine and El Assir, together with Saudi businessman Ali bin Musallam - who together formed what was called the ‘K network’ – were to be paid massive sums, of which they also took a cut. “The intervention by this network covered by Nicolas Bazire and Renaud Donnedieu de Vabres, acting in the name of their respective [government] administrations, is a veritable imposture which had a significant cost in the end for the French state,” concluded the Paris public prosecutor’s office when it advised, in May 2014, that the six should stand trial.

Immediately after Jacques Chirac was elected president in 1995, he ordered an end to all still-outstanding payments of commissions to intermediaries that Balladur's government had put in place, key witnesses have told the investigation.

In the continuing investigation into the murders of the engineers in Pakistan, still led by Judge Marc Trévidic, the theory that the attack was an al-Qaeda plot has been dismissed, while a revenge attack organised by those who were left unpaid is considered a more likely motive. Importantly, the bomb blast took place during the French two-round presidential elections in 2002, when Chirac won a second term of office. A recent lead points to the involvement of members of the Pakistani security services.

Enlargement : Illustration 2

For some while Trévedic, who is joined on the case by a second judge, Laurence Le Vert, has concentrated his investigations on the ‘K network’ lynchpin figure of Ali bin Musallam, a former senior adviser to King Fahd of Saudi Arabia who played a key role in organising the system of retro-commissions from the French weapons sales to Saudi Arabia.

It has been established that Musallam, in collaboration with the Balladur government, supervised the system of massive kickbacks paid from weapons sales contracts with Saudi Arabia in 1994: these were codenamed Mouette (refurbishment of the Saudi Arabia’s French-made frigates), Sawari 2 (the sale of two frigates) and Shola/Slbs (for the arming of Saudi frigates).

In the US investigations that followed the September 11 2001 attacks, Musallam, an Ismaili who was born in 1940 in the Saudi Arabian town of Najran and who died in uncertain circumstances in Geneva in 2004, was identified by both the CIA and the Treasury Department as having served as a financier for al-Qaeda.

Spy chiefs to be questioned

The French investigation believes it probable that Musallam was the person who most lost out financially from the decision by Chirac, after his election in 1995, to cancel the secret commissions France was still due to pay to intermediaries for the Pakistani and Saudi deals.

When the judges sought information on Musallam from the French domestic intelligence services, they were told that nothing about him was available, while several former intelligence staff have refused to answer their questions on the grounds that their answers would breach defence secrecy laws.

Amid widespread suspicions of a politically-motivated cover-up of evidence in the Karachi affair, shared by the relatives of the murdered engineers and survivors of the attack, the continued refusal to divulge key evidence for reasons of defence secrecy has significantly impaired progress in the case.

Last December 4th, judges Trévidic and Le Vert wrote directly to French interior minister Bernard Cazeneuve. “The invocation [by witnesses] of defence secrecy rules, in the absence of any written document that is formally classified, raises a question of principle,” they wrote. “A witness can decide themselves what, in their opinion, constitutes classified information that they could not transmit to the judge.” They requested that Cazeneuve contact the official commission that oversees the application of defence secrecy rules, the CCSDN, in order that it directly questions, itself, those witnesses who refuse to talk to the judges in the hope that their statements might subsequently be declassified.

The judges, whose move was backed by several civil parties to the case, based their request to Cazeneuve on an article of the law governing defence secrecy rules. This stipulates that “the president of the [CCSDN] Commission can lead all appropriate investigations” and that “the members of the commission are authorised to be acquainted with all classified information within the framework of their mission”.

But despite receiving the interior minister’s support, Trévidic and Le Vert’s request was refused outright by the commission’s president, Évelyne Ratte. “I have the honour of informing you that this proposition, which would have the effect of freeing from their constraints people who are required to respect the secrecy of national defence, is neither envisaged nor allowed by the laws in practice and, in that respect, is not compatible by law with the demands of the criminal proceedings,” Ratte wrote to the judges in a letter dated February 9th 2015.

Lawyer Marie Dosé, who represents several survivors of the Karachi attack, immediately wrote a letter to Ratte in which she complained about the “considerable” setback in establishing the truth caused by Ratte's decision “in a case that has for more than a decade run up against defence secrecy rules”.

“The victims I represent are particularly shocked,” wrote the lawyer. “The Commission that you preside had the opportunity of proving, in a case that is particularly sensitive, that it could at last make use of an investigative power that is envisaged by the [legal] texts which it never uses,” Dosé added.

The following month, judges Trévidic and Le Vert came up with a new plan which has now made French legal history and set an important precedent for the many judicial investigations which are blocked by defence secrecy laws. Most importantly, it may soon allow for a breakthrough in the case.

On March 13th they wrote to Cazeneuve with the proposition that they send individual questionnaires to each of the witnesses who previously refused to testify to them on the grounds of the defence secrecy rules. The witnesses’ replies would be sent directly to the interior minister without being seen by the judges. “Thus the people concerned would have no reason for arguing [that they are bound by] national defence secrecy rules so as not to answer the questions put [to them],” they explained in their letter to the interior minister, who accepted the idea.

The legal approach behind the operation, Mediapart has learnt, is that the interior ministry will officially classify the witnesses’ replies, as soon as they are received, under the protection of defence secrecy rules. The CCSDN will then be asked to give its opinion on whether, or not, the witness statements can be declassified, which in any event is a consultative opinion and not a binding one. For, in the final resort, it is the interior minister who must decide whether or not they can be declassified, and to allow him to do so they must of course first be classified.

Mediapart has learnt that the first of the questionnaires were sent out last week. Among the witnesses concerned are members of the former domestic intelligence service the DST, now called the DGSI. These include former DST head Jean-Jacques Pascal, his deputy Raymond Nart, two former DST directors, Éric Bellemin-Comte and Jean-Jacques Martini, and a DST desk officer who, in statements seen by Mediapart, is only referred to under his alias ‘Verger’.

-------------------------

- This is an extended version, with additional background information, of Fabrice Arfi's original article in French which can be found here.

English version by Graham Tearse