French rule over Algeria began in 1830 and would end in 1962 after seven years of a ferocious conflict between the pro-independence FLN (National Liberation Front) and the French military, in which hundreds of thousands died, including civilians, and when barbaric acts were committed by both sides. It led to a massive exodus of European, mostly French, settlers, generations of whom had been present in the colony.

In November 1956, General Raoul Salan was appointed as the commander-in-chief of French forces in Algeria, where long-simmering resentment over French colonial rule had erupted into a war of independence two years earlier. He had previously served in the 1946-1954 First Indochina War, which ended in defeat for France and the partition of its former colony of Vietnam.

When General Salan arrived in Algeria to take up his new post in December 1956, what would become known as the Battle of Algiers had already begun. This was when the FLN launched a terrorist and urban warfare campaign in the city against both the French army and the settlers. Alongside reciprocal acts of terrorism by groups of settlers, the army responded with a fierce and brutal crackdown, which included the torture and extra-judicial killings of prisoners.

Historian Fabrice Riceputi is an associate researcher with the Institut d’histoire du temps présent (IHTP), specialised in research into the events of the 1954-1962 Algerian war of independence, and notably the detention, torture and disappearances of detainees practiced by the French army. In his article below, he traces the process with which, after Salan’s arrival in Algeria, the military were ordered to generalise torture during interrogations of prisoners.

-------------------------

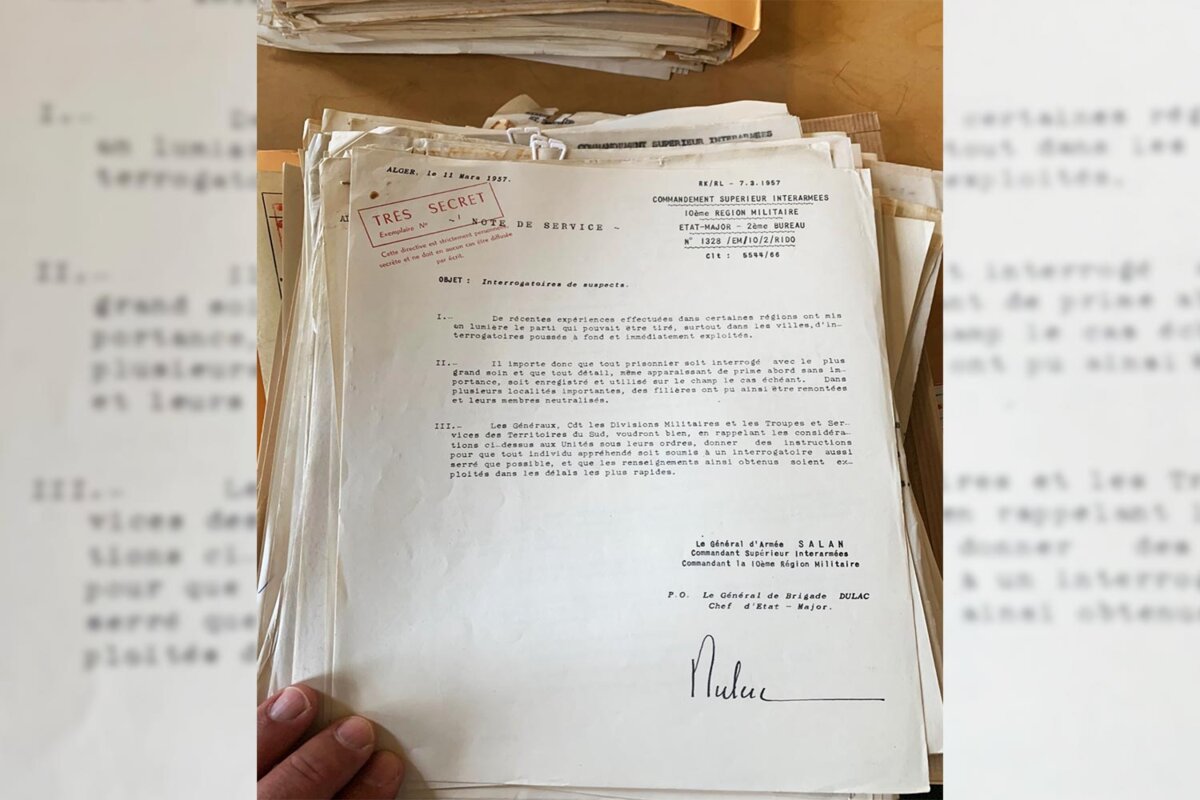

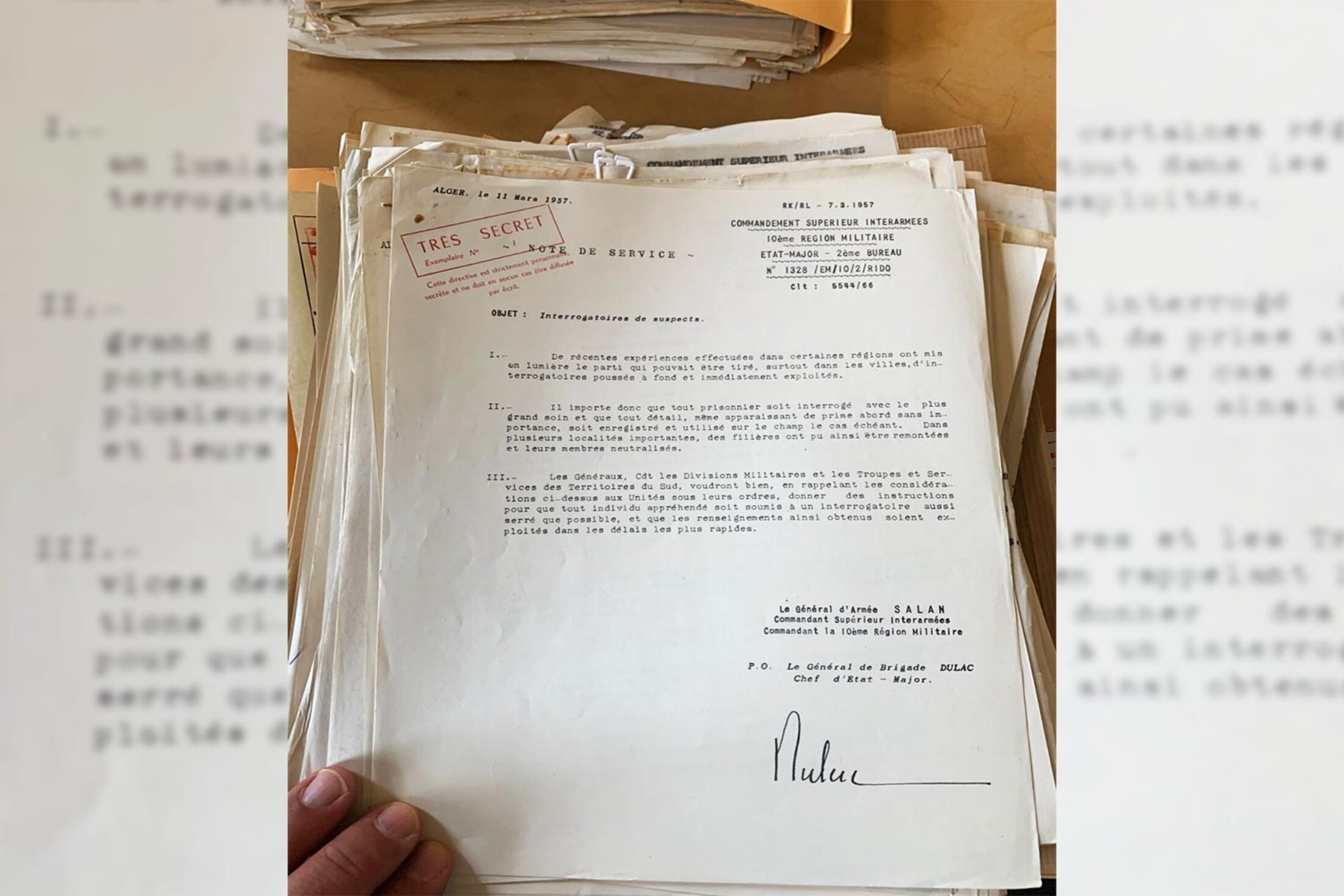

In the French military archives of the Service historique de la Défense (SHD) is a typed note dated March 11th 1957, containing three numbered paragraphs and signed by General Raoul Salan, the commander-in-chief of French forces in Algeria. Entitled “interrogations of suspects”, it was addressed to all commanding officers in the French colony.

The document detailed:

- "Recent experiences in certain regions have brought to light the benefit that can be had, notably in towns, of thorough interrogations that are immediately made use of.

- It is important that every prisoner is interrogated with the greatest attention, and that every detail, even that which at first glance appears unimportant, be recorded and used immediately if need be. In several important places, networks have in this manner been traced through to the top and their members neutralized.

- Generals, Military Division commanders and the Troops and Services of the Southern Territories, are requested, while reminding units under their orders of the above considerations, to give instructions that any arrested individual be submitted to an interrogation as tight as possible, and that the information thus obtained be used in the fastest time."

This “note” was an imperative instruction sent to all commanding officers who would pass the general’s orders on to their units across Algeria. But they were to do so orally; stamped in red ink on the document were the words “Very secret”, followed by the warning: “This directive is strictly personal and must not in any event be circulated in writing”. That was true of many of the general’s directives, but none were as secret as these instructions.

Enlargement : Illustration 1

The wording was carefully chosen in order to avoid the risk of embarrassing accusations or even, if the French political scene changed shape, prosecution. At the time, torture was considered, as it is today, a crime, largely disapproved of on moral grounds and which reminded many among the French population – some of who openly said as much – of the methods of the Gestapo and the SS during Germany’s wartime occupation of France. Also at that very time, in April 1957, French prime minister Guy Mollet (whose official title then was president of the council of ministers), swore before TV cameras and radio microphones that France, the birthplace of “the rights of man”, was incapable of practising torture.

For the general, linguistic camouflage was the order of the day.

What the general was telling his officers was certainly not that they should “interrogate” suspects who are believed to have information about the nationalist Algerian “rebellion”, for they were always interrogated. What Salan was telling officers in the document was how they should henceforth carry out interrogations everywhere – “thorough” and “as tight as possible”. This amounts to inflicting enough pain on a “suspect” so that their resistance to talking - giving information - is overcome, which is the very definition of torture.

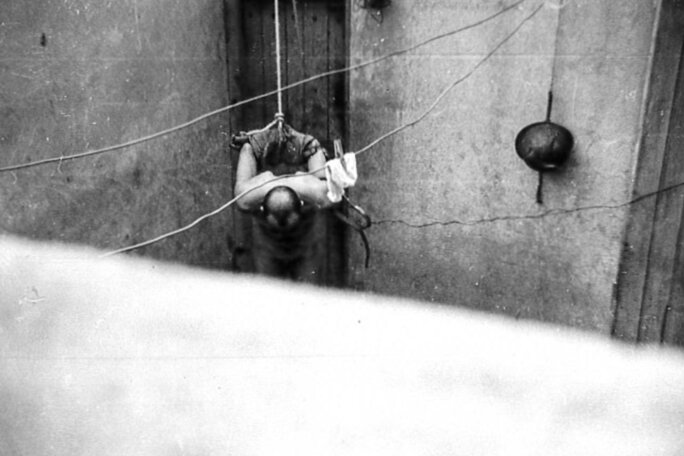

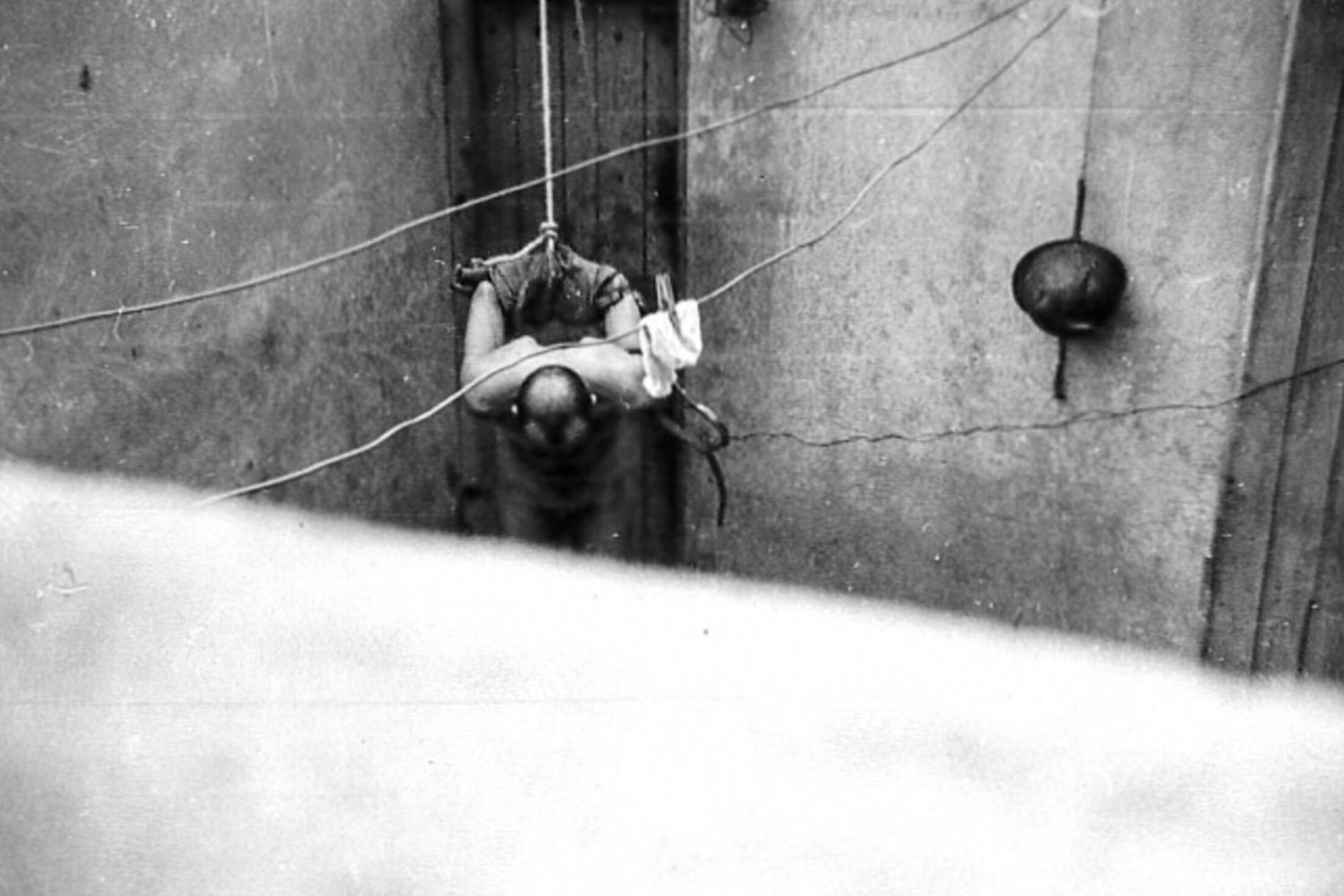

The military personnel to whom he addressed the instructions were already aware of the means to administer torture, which was in use among sections of the French army since the war in Indochina. During interrogations regularly described – as well as “tight” and “thorough” – as “energetic”, “hard”, “with force”, and “muscular”, it was advised that interrogators use electric shocks using portable generators (nicknamed “gégènes” by the French military) and also mock drowning (nicknamed the “baignoire”, from the French for for “bath”), which were techniques that allowed interrogators to increase the suffering of the prisoner while supposedly leaving hardly any traces on their body. But many other forms of torture, crueller still, have been recorded.

Enlargement : Illustration 2

On March 10th 1957, the day before Salan’s circular advising, in thinly disguised terms, on the use of torture, General Jacques Massu, who commanded the 10th Parachute Division, addressed his men with advice of his own on the subject. From early January that year, Massu’s four regiments, sent into Algiers to eradicate the FLN attacks in the city, carried out house raids, arrests and the torture of prisoners, before the FLN campaign was finally defeated in the autumn of 1957. Massu’s March 10th note to his men read: “With the aim of efficiency, persuasion must be used to the maximum,” he wrote. “When that is insufficient, there is reason to apply the methods of coercion about which a specific instruction has detailed the sense and limits.”

The “specific instruction” Massu referred to could not be found among the French military archives (the SHD). But Jacques Inrep, who served in the French army as a conscript during the independence war, and who is an outspoken critic of the torture practiced by the army, has said he came across it in a French army office in the town of Batna, north-east Algeria, in 1959. According to him it contained “several graduations” of treatment to be meted out against a prisoner during a “thorough” interrogation.

It was well after the end of the Algerian war of independence that Massu recognised and justified the army’s use of torture, in his book La Vraie Bataille d'Alger (the real Battle of Algiers) published in 1971, although he later publicly expressed his regrets that it was practised.

On March 23rd 1957, it was general Jacques Allard, in command of the French army’s Algiers corps, who relayed the instructions handed down from Massu and Salan in another note, in which he wrote that “the procedures employed in Algiers and which have been proven to be effective” should be generalised.

Three months after the Battle of Algiers began in earnest at the beginning of 1957, the French army generalised the practice of torturing Algerians. While the use of torture had already been regarded as necessary and normal within police stations in Algeria before the start of the independence war, as testified by several official reports cited by French historian Pierre Vidal-Naquet in his 2002 book La Raison d’État, its widespread use during the Algiers crackdown turned it into a “clandestine institution”, to quote Vidal-Naquet. According to he doctrine of the counter-insurrection war adopted by the defence ministry after France’s defeat in Indochina, it was at the heart of military and police action.

The practice of forced disappearances

Another secret directive signed by General Salan, issued in January 1957, advised a method for obtaining information about the activities of the FLN and its armed wing, the National Liberation Army (ALN). This was “the provisional and surprise kidnapping […] of several inhabitants taken at random, or identified as suspects, with the aim of an interrogation”. Thus all Algerians could be considered as targets because they were, to Salan’s thinking, likely to know about rebel activities or are themselves involved in such activities.

The method was already employed in rural zones where the ALN was present, but in 1957 in Algiers it took the form of massive and repeated raids in Muslim neighbourhoods, when thousands of people would be subjected to checks and hundreds held for further interrogation. As General Massu later wrote in his memoirs, the “interrogation centres – in reality torture centres – were multiplied. The clandestine detentions, without witnesses or any civilian control, encouraged the massive use of torture and the practice of summary executions which continued in the colony until the end of the war.

This military and police regime of terror to which Algerian men and women were subjected was very similar to that later established in Argentina, Chile and Syria (the difference being that in Algeria it was in a colonial context). It was only much later, after the recorded and reported events under dictatorships in South America, that “forced disappearances” (also called enforced disappearances) became defined as a crime against humanity under international law.

The responsibility of the French state

It should be underlined that the practice was authorised by the socialist government of prime minister Guy Mollet, and in turn, the French state.

Two years after the beginning of the Algerian insurrection, the French government found itself in a desperate situation and ready to do anything to restore colonial order. It was faced with the growing political and military strength of the FLN (which planned an eight-day general strike against colonial rule), and the anger and fear of European settlers many of who wanted the army to take over political power.

Mollet and his ministers Robert Lacoste, Maurice Bourgès-Maunoury and François Mitterrand, turning their backs to the path of a political solution, agreed to all the demands of the military who made the wild pledge of definitively eradicating Algerian nationalism in Algiers, the showcase city of French Algeria (which would become the capital after independence).

By virtue of a “special powers” law approved by a large majority in parliament in March 1956, the military were given a raft of new powers in Algeria, including that of deciding who was a “suspect” to be detained and interrogated, and exonerating the army from any legal constraint. The government was well aware that this implicitly gave the military a green light for torture and executions.

From that political decision, the numbers of victims, with no distinction made of gender, age or racial origins, would reach tens of thousands up until independence was gained in 1962. Subsequently, soon after the conclusion of the Evian Accords that sealed Algerian independence, the French state, under the presidency of Charles de Gaulle, granted itself by decree an amnesty for those crimes.

-------------------------

- The original French version of this article can be found here.

English version, with some added reporting, by Graham Tearse