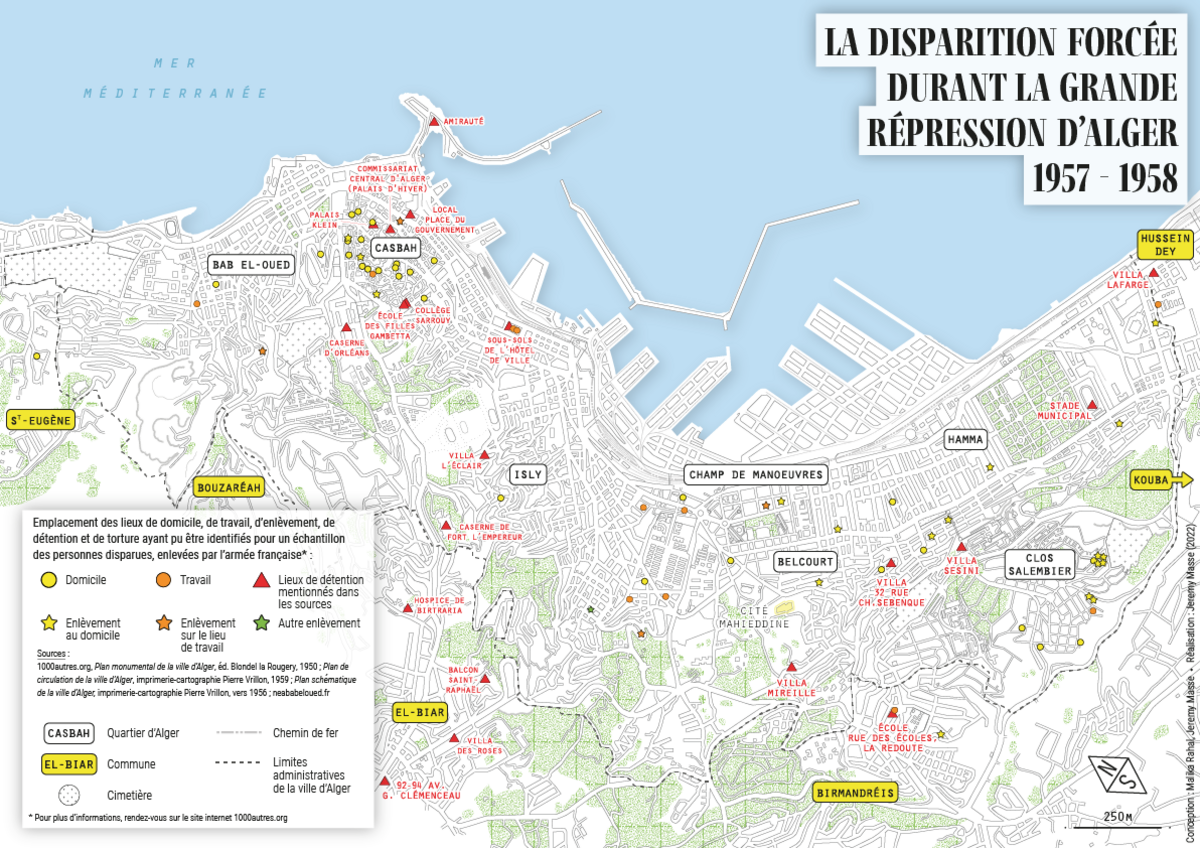

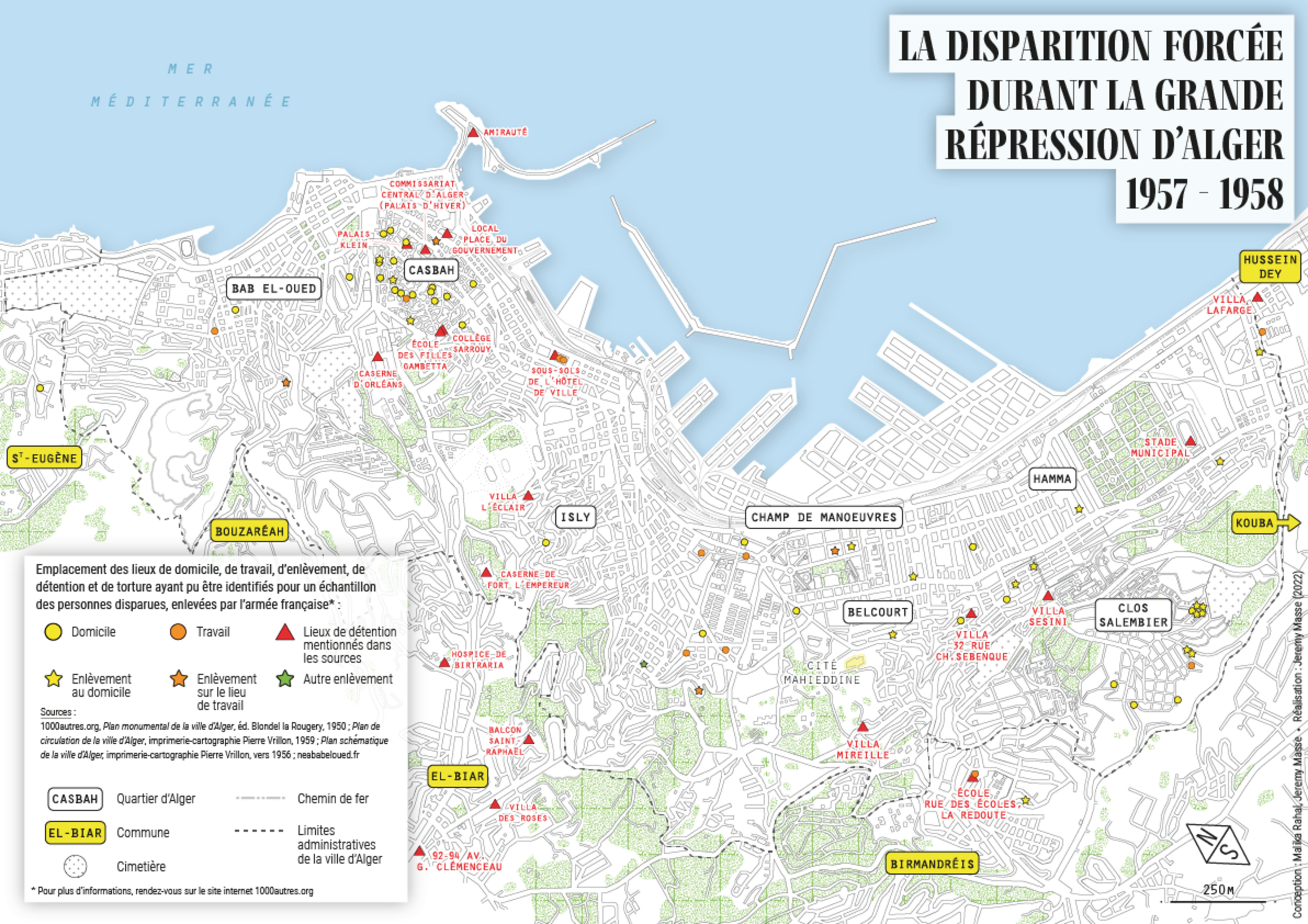

We had been working in Algiers for 15 days, carrying out research for the project Mille autres — Des Maurice Audin par milliers on the series of disappearances of men and women kidnapped by the French army in Algiers in 1957 [during the 1954-1962 Algerian war of independence]. One of the aims of the research was to locate sites which sources had indicated were used for the detention and torture of those who disappeared.

On November 16th 2022, we discovered a place, which several sources had mentioned, where Algerians were secretly detained and tortured, and sometimes killed by the French army. This was the Perrin farm.

Locating the centres used for torture in Algiers and the surrounding region, 60 years after the events, is both complex and uncertain. Some of these places are well known and preserved, such as the Villa Sésini or various French army barracks which have since become barracks for the Algerian army. But many others have, since Algeria gained its independence, been reoccupied, some lived in. There are those that have changed hands on several occasions, and even changed names, since 1962. Others are localised without any certainty.

Yet others have been destroyed, like La Grande Terrasse, a restaurant in what was in colonial times called Saint-Eugène (see map below), a municipality within Algiers now renamed Bologhine. It was requisitioned by French parachutists led by general Jacques Massu, and who used its cellars as torture chambers. That was recently confirmed by several eye witnesses of what went on there, including Roland Bellan, the son of the restaurant’s proprietor. The site was located for us by Mohamed Rebah, a historian who was also a witness of the events. He is one of the contributors to our project and his input has proved essential.

We had to make several attempts to find the Villa Mireille, which at the time of the events in 1957 was located at 51, boulevard Bru (now renamed boulevard of the Martyrs). Those who were tortured there were sometimes ‘fixed up’ before being brought before a judge. They were mostly European detainees, targeted by the colonial violence because of their support for Algerian independence. A neighbour of the site, Rachid Guesmia, who is another precious contributor to our project, was at the time one of the children from the neighbourhood, who believed the building was haunted.

Enlargement : Illustration 1

It was easier to locate the former Sarrouy school, which sits in the Soustara quarter close to the Casbah. In the summer of 1957, it was transformed into a torture centre by the 2e RPC [editor’s note, a French parachute regiment]. Our mapping of the story of the forced disappearances is progressing.

Several former colonial farms also feature in our list of torture centres. On the outskirts of Algiers, they were, variously, lent to the French army during the war by their owners, or were requisitioned. It was on one of the farms, according to French general Paul Aussaresses, that [editor’s note, prominent early leader of the Algerian independence movement] Larbi Ben M’Hidi was assassinated.

On November 16th 2022, we were trying to trace one of these farms, accompanied by archivist and colleague Mohamed Bounaama, who had informed us about it. Located close to his place of work, in the area of the former Laquière farm, at Tixeraïne (a part of Birkhadem, now a suburb of Algiers), it had sometimes been said that the French army used it to detain and torture people. Bounaama accompanied us because a mechanic in the neighbourhood had told him about another torture centre nearby. This was the Lambard (or Lombard, Haouch Lombar) farm.

A simple search on the internet showed that it had recently been included on GoogleMaps, and that it is also called “the Perrin farm”.

That name was intriguing. It sent us back to the case of Ali Boumendjel, a lawyer who was kidnapped on February 9th 1957, tortured and subsequently ‘suicided’ [editor’s note, in reality executed] on March 23rd 1957, and whose story is told in a book by Malika Rahal, co-author of this article. Several sources confirmed that Boumendjel had been taken to the Perrin farm at an unspecified moment during that period. Lawyer Maurice Garçon, a member of the Commission de sauvegarde [editor’s note, a 1957-1963 French commission to investigate human rights abuses by French forces in Algeria], indicated simply that Boumendjel had been at the farm.

Benali Boukort, a former militant with the pro-independence Democratic Union of the Algerian Manifesto and later the Algerian People’s Party, gave an important account on this subject in his memoirs. Arrested on March 2nd 1957 and detained at the Perrin farm (Haouch Perrin), he gave a precise description of the place, which he said was a large wine-producing colonist’s farmhouse and vineyard, and whose installations were used for other purposes than for which they were originally intended.

When kidnapped people were transported there in daylight, they arrived in a covered-over trailer and parked in what he called “a place surrounded by barbed wire and guarded by several parachutists”. After two or three days they were transferred to the empty vinyard wine vats. Such practices existed elsewhere in Algeria; several cases were revealed in 1957 of the deaths by suffocation of dozens of detained Algerians in the containers.

Benali Boukort said Ali Boumendjel had been kept in the place, and held alone in an empty wine vat. In this, his account is corroborated by Boumendjel’s brother-in-law, Abdelmalik Amrani, who was also held on the Perrin farm. After the war, Amrani told his sister, Malika Boumendjel Amrani, and his son Aïssa, that, being held in a vat alongside that in which Boumendjel was placed, he was able to communicate with the lawyer.

During the writing of the book about Ali Boumendjel, it had not been possible to locate the farm, its precise site remaining a mystery. We endeavoured to find it.

The zone is today densely urbanised and absorbed into the agglomeration of Algiers. Local inhabitants recognised the name of the farm as Perrin rather than Lambard, and that it now indicated a neighbourhood. One of them, a young woman, told our colleague Mohamed Bounaama that we should continue along a street to its end. The whole of the street is commonly named “Perrin”.

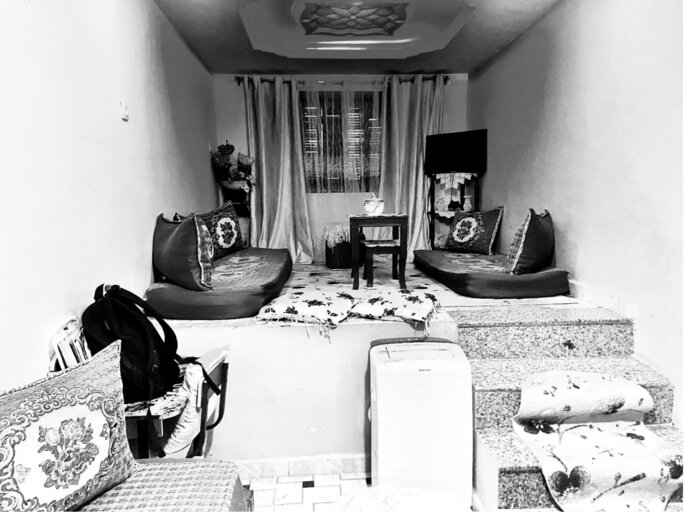

There we entered, through a large gate, a little square planted with trees. The former vast agricultural domain no longer exists. Little alleyways lead off from the square, bordered by small, low-lying houses which, to all evidence, were built after the end of the independence war in 1962. But, facing us, was a villa with a tiled, sloping double-roof, and which stood out against the other, more recent, neighbouring buildings.

Enlargement : Illustration 2

To the right of it was an open gate leading to another tiled-roof structure, which was manifestly a former agricultural building or part of a farmyard. We entered and knocked on the door.

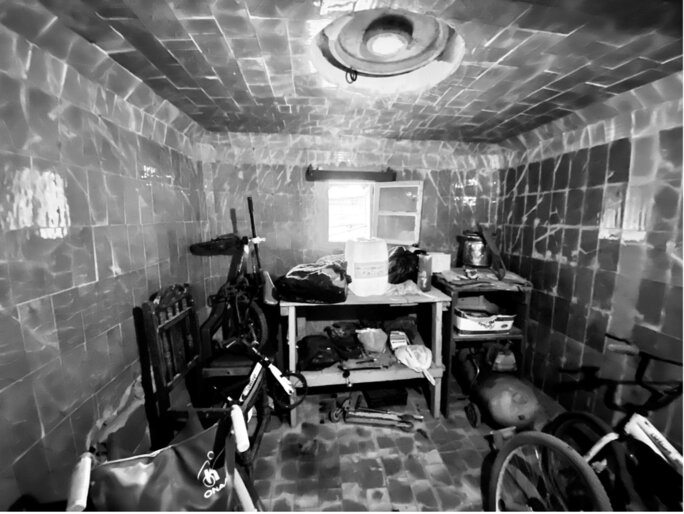

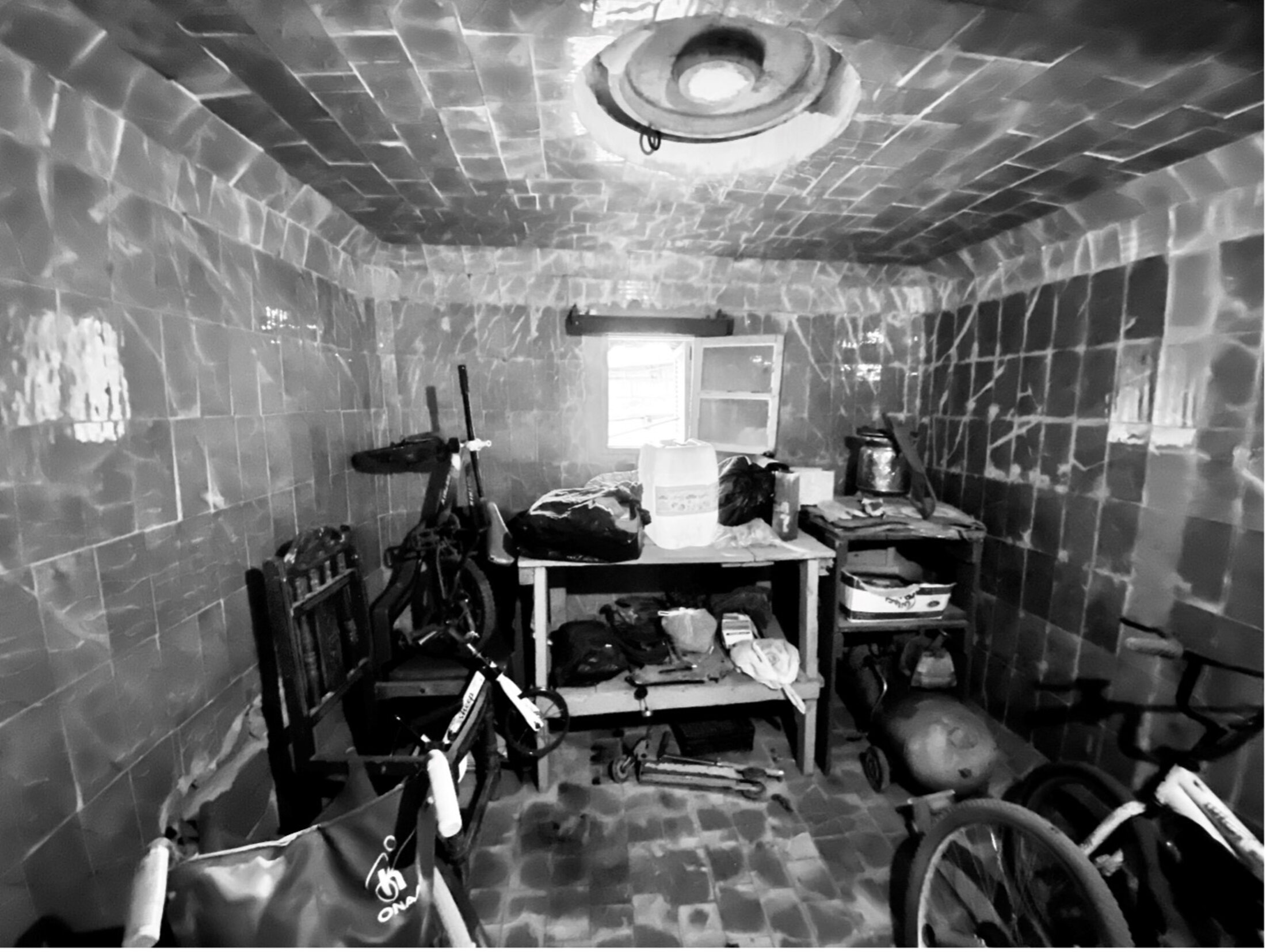

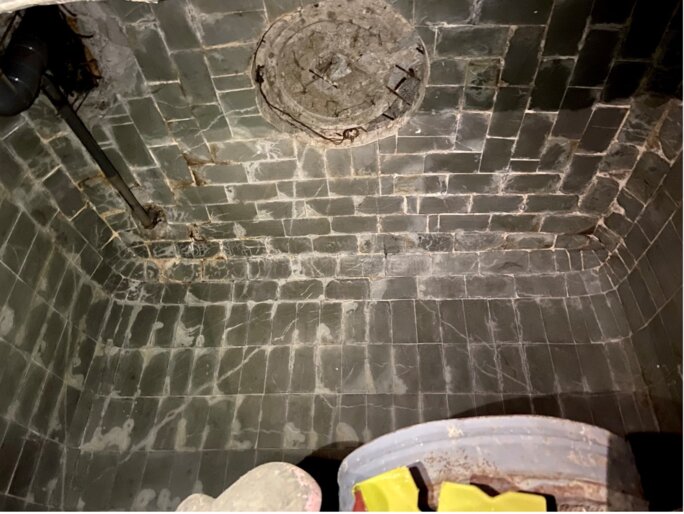

We explained to the man who greeted us that we are historians and were looking for wine vats in which, during the war of independence, mujahideen [editor’s note, the name given to independence militants] were kept. He agreed to show them to us and cordially invited us into what turned out to be his home. We first entered with him into a room of about three or four square metres, entirely covered with grey-green earthenware tiles, and which he used as a storeroom. “It’s there,” he said simply without us at first understanding what to look for.

Enlargement : Illustration 3

When we raised our heads, we got a shock. In the tiled ceiling was what was once circular opening, roughly 60 or 80 centimetres in diameter, now closed by a big ‘cork’ of cement. We realised we were inside a former wine vat, into which the kidnapped detainees were placed or removed via the now cemented hole. It might have been that where Ali Boumendjel or Abdelmalik Amrani were held. The current occupants had simply knocked down parts of the former vats to make doorways between them, and windows to let in light. They serve as a sort of modular lodging inside the farm building.

This unexpected discovery was moving. To have read about the accounts that mentioned these vats, and the asphyxiation of the prisoners dropped into them is one thing. But to find oneself by chance within one of them is quite another. We were facing an archaeological example of the terror that once reigned there, and in our minds we constantly compared what we were seeing with the accounts of our historical sources.

To be on the site allowed, with years of distance, to better understand the description that Benali Boukort gave in his book. He wrote of similar vats as “little buildings of bricks, with barely two or three metres at the base”. Without doubt, he could not have imagined then that they could later serve as habitations within the city of Algiers, whose agglomeration would invade the rural area surrounding them.

Enlargement : Illustration 4

Boukort recalled that access to the vat was “by a hole of 60 to 70 centimetres” – which we were now looking at. “Some corpulent detainees could not pass through it,” he wrote. “So the paras lifted up the flagstone that served as the lid and dropped them down at the end of a cord that was passed under their armpits. Each vat contained six or seven people. The extreme narrowness did not allow the detainees to lie down. They had to remain constantly crouched, often for 15 days in a row. They only left this uncomfortable and painful position to go for the interrogations.”

We contemplated the spaces, which the doorways had now made airy, to try to imagine seven people in the small surface of the vat, surrounded by thick walls, with a low and curved roof that gives the impression of being in a jar. We passed from one former vat to another. The building has 12 of them, which today are transformed into two distinct habitations.

The grey-green tiles which we at first thought were added recently to improve the comfort of the rooms were in fact original to the farm, and ensured the vats were impermeable in order to protect the wine. It was this protective sealing that made the vats all the more deadly for prisoners. “Sometimes,” wrote Benali Boukort, “according to the mood of a guard, or when the paras were annoyed with a detainee, the opening was obstructed by a sack. Several deaths from asphyxiation were caused this way.”

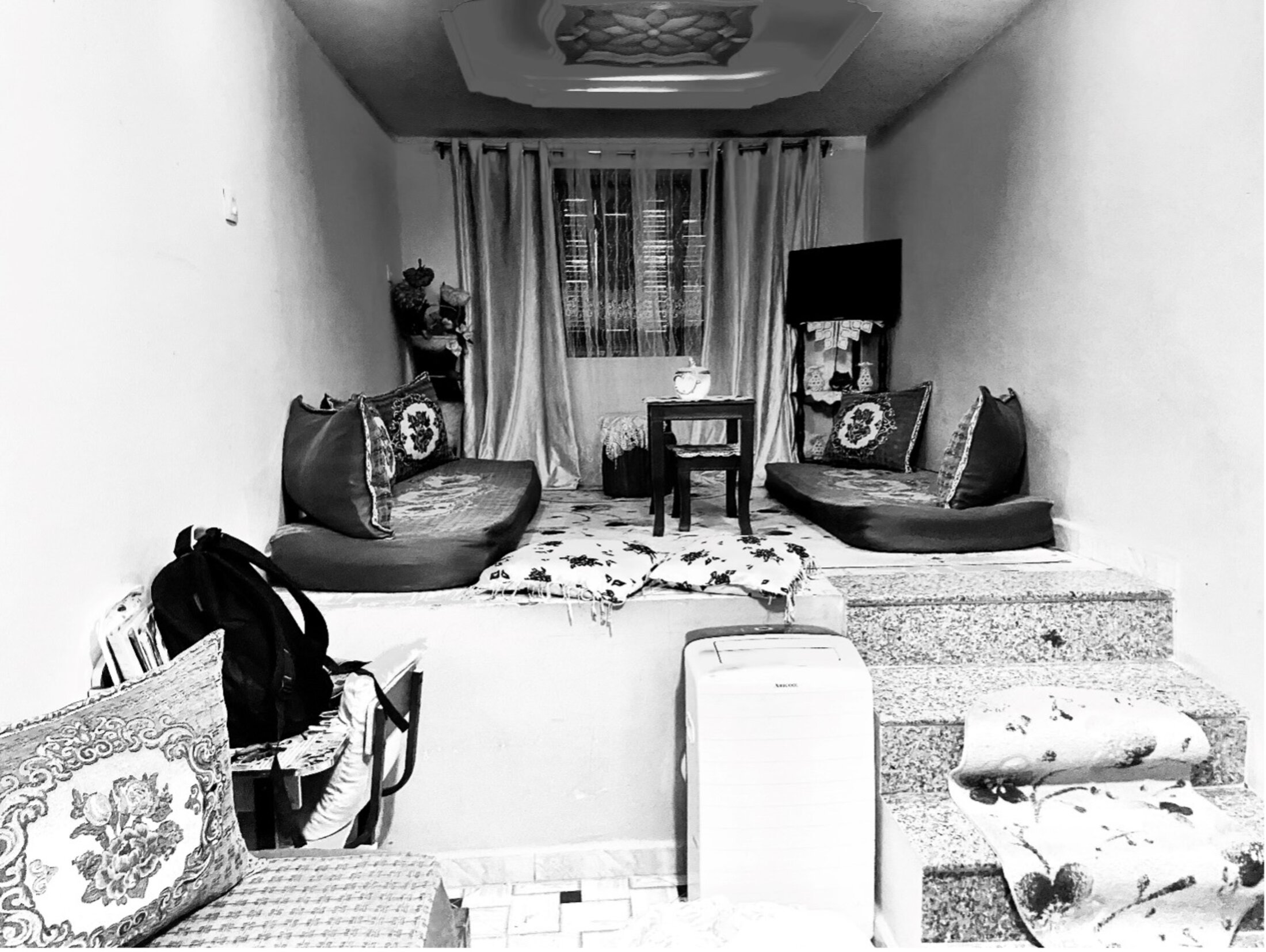

The inhabitants, who moved in during the 1970s, are perfectly aware of what happened in these places. Together with them, we talked about the horrors that took place here during the independence the war, but without any great emotion because it is now part of their daily life. They would like to move elsewhere. The father of the man who guided us might have been able to tell us things, but he is deaf and did not understand the purpose of our visit. He asked Malika Rahal on several occasions whether she was from the government and if she had come to help them be re-housed. His other son lives in the second house made up of the vats, where several of them have been opened up to form large rooms. His living room is created from three vats.

Enlargement : Illustration 5

One vat, at the back of an elevated kitchen, remains unused and is barely accessible. But our guide wanted to show it to us because there is something inside still visible and which has been removed from the other, transformed vats. To get into it, one has to climb onto the kitchen counter and pass through a small opening. On the floor, as he moved aside the objects stored there, he presented four metal rings fixed to the ground.

Enlargement : Illustration 6

According to him, these were to attach prisoners to. They indeed appeared to have been added after the vats were built and when used for storing wine, for the rings would have damaged the impermeable nature of the vats, and would have rusted if covered in wine.

According to him, these were for attaching prisoners. They indeed appeared to have been added after the vats were used for storing wine, for the rings would have damaged the impermeable nature of the vats, and would have rusted if covered in wine.

After we left the habitations, a group of neighbours had gathered back at the small square. We learnt that the names Lambard (or possibly Lombard) and Perrin were those of two successive owners of the domain. Lambard had bought it from an individual called Bouchahma, and Perrin subsequently bought it from Lambard.

Everyone appeared to know what happened here during the war of independence. In the courtyard of the farm building, to the right, were the vats where the prisoners were kept. To the left of the building was where the ‘gardes mobiles’ [editor’s note, a military gendarmerie unit that served as back-up to the regular army] were stationed and where the torture was carried out. We were told that the cries of the prisoners’ could be heard outside. Then, in 1962 or 1963, at the moment Algeria obtained independence, the domain became a self-managed business, like many other colonial farms.

A Mr Lounès, who joined us, said he had been a member of the self-management committee. He recounted that it was in 1962 when, inside the building, sacks were found amid a disorderly collection of items, along with traces of blood. According to him, the farmyard site regained its agricultural use, and workers who had come from far away were the only people to sleep there. He didn’t say whether the vats themselves were again used for wine production.

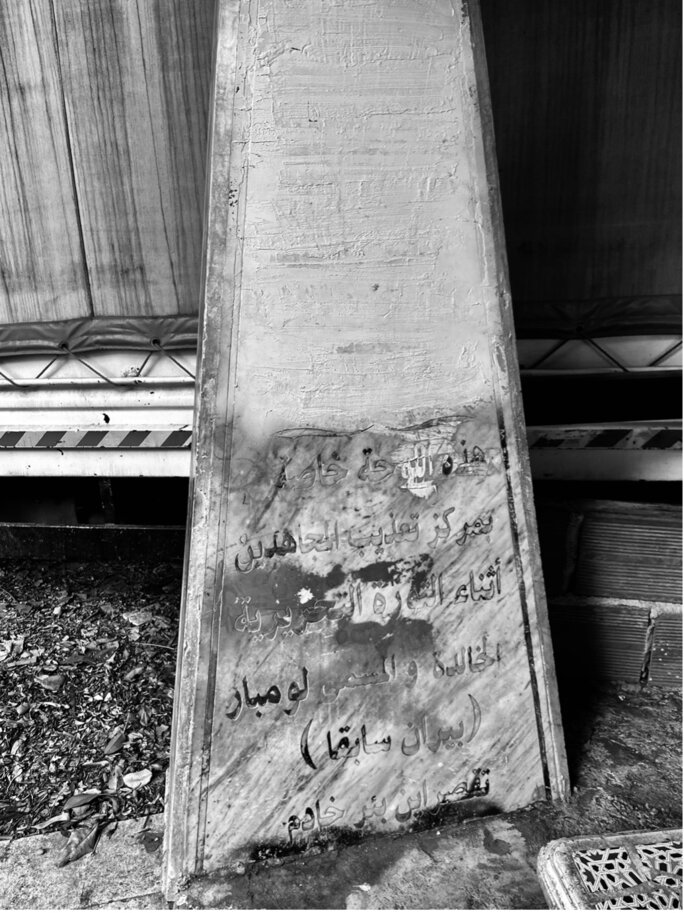

Enlargement : Illustration 7

The group who talked with us showed us a discrete monument which we hadn’t noticed until then. This was an obelisk, of which a part had been repainted in white to cover over a Koranic verse that contained a mistake. But the rest of the text on the obelisk indicated that here was a “centre for the torture of mujahedeen”, and it carried two names; Lombard and Perrin. It appears to have been placed there by the local municipal authorities at the end of the “Black Decade” of the 1990s.

The time came for us to leave.

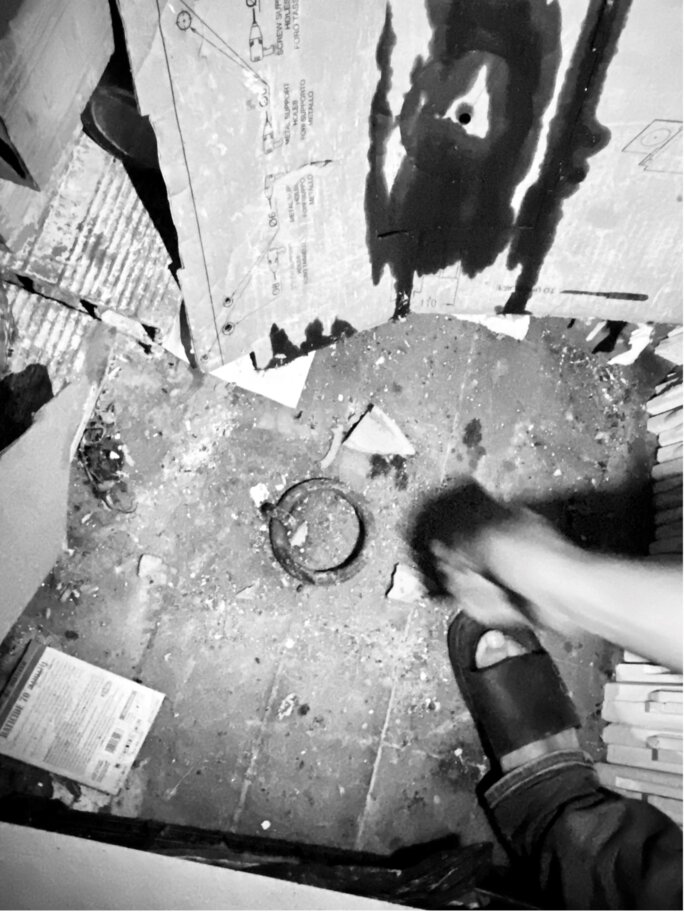

However, we hadn’t finished with the Perrin farm. Someone tapped on the car window. He was another neighbour, who we had thought was absent, and he invited us to visit the villa with the sloping double roof, where in all probability once lived Lombard and, later, Perrin. The man told us his family have lived there since 1963. In the courtyard, he first showed us a single-storey building which he said had once served as “the offices” of the gardes mobiles. Then he opened a large wooden door, which he said dated “from the time”.

This led onto about ten steps that descended into a vast and deep cellar, which was lit up through slender openings of around four metres in height. The man showed us several circular imprints, and another that was rectangular, across the floor. He recounted that these were the still visible spots where there had been holes of around 1.5 metres deep, and which had since been filled in by his father.

Enlargement : Illustration 8

Our guide, born after Algeria gained independence, said that before his father had filled-in the holes, he had seen, at the bottom of one of them, a long chain. He detailed that the holes were where prisoners were kept, crouched. He added that the holes were filled with water to heighten the suffering of the detainees. The rectangular hole, which was narrower and deeper, could not allow for a person to crouch, rather they would have necessarily been forced to stand. We wanted to reconstitute precisely how this account came about, whether it was from eye witness reports, or whether it amounted to the suppositions by the family who arrived there at the beginning of independence, and based on what they had known about.

In his own account, Benali Boukort does not mention these holes in the floor. According to him, those detained on the Perrin farm suffered regular torture sessions in which electricity and water were used, as happened in several torture centres. But there also existed a speciality that consisted of causing wounds with a plane [editor’s note, a carpenter’s wood-shaving tool that has a flat side with a sharp blade in it] before covering them with salt.

These torture sessions, called “interrogations” were, wrote Boukort, held “in the presence of gendarmes, agents from the DST [French domestic intelligence] or the Deuxième Bureau [military intelligence]”. Was the plane used in this room? All the objects present raise questions for us, notably the hook in the high ceiling from which hangs a chain. We can’t prevent ourselves from imagining that men could have been tortured here by being suspended from above, as was practiced elsewhere. But how can we find out?

Enlargement : Illustration 9

We know about one man, Mohand Selhi, who was detained and murdered here. According to Benali Boukort, Selhi, who was also kidnapped in 1957 during the nine-month Battle of Algiers, was detained in a vat along with five others. “For 18 days, Selhi was subjected to up to three sessions of torture per day,” wrote Boukort. “One evening, he was executed like the others. Aged 35, he was an engineer for the company Shell.”

Our work into the forced disappearances in what is also called the 1957 “Great Repression in Algiers”, has taught us that, for the families of those who disappeared, the one thing more important than any other is to know where the body is, to be able mark their respects at a precise spot, and to know how they died.

As we left the Perrin farm, we had a number of hypotheses. One was that perhaps the bodies of those who died here were buried close to the house and farmyard, somewhere on the domain. In the detention and torture centres situated in the towns, the French military discretely took the bodies to burial sites far away. At the Perrin farm they could bury the dead on-site, in the old vineyard and the surrounding fields, land which is now entirely covered with small houses.

This surprise visit of the farm, and all our mission of research in Algiers, confirmed that for the local population, the terrible memories of the “great repression” of 1957 are still present, in the form of direct witness accounts and those that have been handed down. Even if one has the sentiment that, over the years, the events are ever more distant, these witness accounts and handed down stories, which historiography has neglected for too long, are still teeming. They provide us with precious information that the colonial archives, by definition, ignore.

They must be collected before they become forgotten and disappear. In a few years’ time, it will no longer be possible to distinguish, as one can still do, between the first-hand witness accounts and the conjectures of the new inhabitants of the sites.

But there is every reason to believe that they who now live in the immediate vicinity of the former centres of detention and torture will continue, as several among them told us, to feel the presence of those who were taken there, and even sometimes imagine a ghost pass by.

-------------------------

Malika Rahal is a historian and director of the Institut d’histoire du temps présent (IHTP), affiliated to France’s National Centre for Scientific Research (CNRS), and is the author of several books about the history of the Algerian independence movement. Secondary school teacher Fabrice Riceputi is an associate researcher with the IHTP, specialised in the history of the late period of French colonial rule in Algeria, and is notably the author of Ici on noya les Algériens (“Here they drowned the Algerians”) about the Paris police massacre of Algerians demonstrating in favour of independence in October 1961.

Their project, Mille autres — Des Maurice Audin par milliers, is dedicated to discovering what happened to the victims of the forced disappearences in Algiers in 1957. It includes a list of the men and women known to be among them, along with a public appeal for information about their fate.

-------------------------

- The original French version of this text can be found here.

English version by Graham Tearse