It was shortly after 1 p.m. on Friday January 9th 2015 when a man wrapped in a black down jacket with a fur-lined hood strolled along the pavement outside the Hyper Cacher kosher store at the Porte de Vincennes on the south-east edge of Paris. While he was walking he attached a GoPro camera on his stomach before coming to a halt beside the entrance to the Jewish shop.

He placed on the ground from his shoulder a sports holdall bag he was carrying and rummaged inside it, pushing one automatic rifle to one side and grabbing a second. The curved magazine placed against his thigh, the forefinger of his right hand on the trigger, he strapped the holdall back over his shoulder. Facing the entrance of the kosher store he fired at the figures inside.

Enlargement : Illustration 1

Yohan Cohen, a 20-year-old store employee who was tidying up the chain of trolleys at the entrance, fell to the floor, bawling in pain. He had been shot through the cheek. Coulibaly was then inside the kosher store and fired off more rounds. He again shot Yohan Cohen, who had been shouting to his manager for help, this time in the stomach.

Coulibaly went on to shoot dead three other men before he was himself killed during the police assault on the store at about 5 p.m.

The gun that killed the Yohan Cohen was a VZ-58 assault rifle made by the Czech firm Ceska Zbrojovka. In itself, that firearm sums up the repeated failures, in the name of free movement of goods, of European gun control legislation over a period almost ten years.

Nine media organizations, including Mediapart, grouped together in a journalistic collective called European Investigative Collaborations, set out to trace the history, from its moment of production to the terrorist massacres in Paris in January 2015, of a killer’s gun (see Black Box section bottom of page).

It is estimated that within the European Union (EU) there are 80 million legally-kept firearms. It is however quite easy to divert a gun from its legal usage and turn it into a criminal weapon. The automatic rifle with which Amedy Coulabily shot and murdered Yohan Cohen is one of them. Made more than five decades ago, in 1964, French forensic experts were to find, under successive layers of paint, the stamp of Kol Arms, a gunsmith business situated in what is now Slovakia. Like the vast majority of guns that gave the terrorists the mmeans to commit massacres in Paris in January and November last year, Coulibaly’s VZ-58 was part of a stock of arms from the former Soviet Union satellite countries of Eastern Europe.

Enlargement : Illustration 2

Since the collapse of the Soviet Union, the European authorities have proved incapable over the years of ensuring the destruction or the truly effective disarming of these weapons. That has been a bonanza for the black market and, ultimately, the criminals and terrorists who buy them, as illustrated in the 2005 Andrew Niccol film Lord of War, which was based on the true life story of Russian arms dealer Viktor Bout. According to EU figures, at least 500,000 lost or stolen weapons remain missing among member-states.

The VZ-58 (serial number 63622) which was used by Coulibaly to murder Yohan Cohen was supposed to have been disarmed - made unusable except for firing blanks – in Slovakia in 2014. Such modified weapons are classed as a category “D” weapon in Slovakia, meaning that in can be freely bought by any adult. They can be found in gun shops or bought via the internet for a few hundred euros, delivered by post.

Enlargement : Illustration 3

There are countless examples of this on French police records. During an investigation into an arms dealing ring in the Paris suburbs in 2012, the police came across messages exchanged, using pseudonyms, with hunting and shooters’ websites. The dealers called for offers for weapons they had in stock, illustrated in photos, while occasionally slashing their prices according to the profile of the client or their latest goods. One message announced that “I’ll soon have third-generation Glock 17s”. Rare and much requested Kalashnikov AK-47 automatic rifles sold out quickly. “You’ll have to wait a bit because they sell fast and the one that was here was already booked,” wrote one arms dealer to friend of a jihadist placed in preventive detention in a case involving Amedy Coulibaly and Chérif Kouachi, who with his brother Saïd, carried out the January 2015 shooting massacre at the Paris offices of Charlie Hebdo magazine. “The AKs will be here before Christmas,” wrote another dealer to the same person.

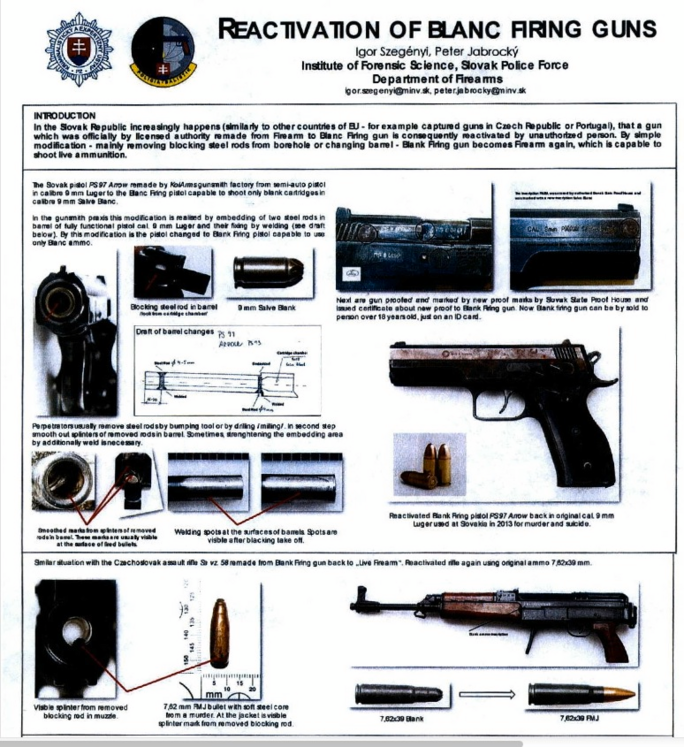

“This procedure is in France completely illegal, but in practice easy,” observed a report by the French police’s Paris forensic laboratory presenting its analysis of Coulibaly’s weapons. For the re-arming of a disarmed weapon is child’s play for someone with proper knowledge. From being made inoffensive, the firearm returns to its killing potential. Despite numerous warnings on the issue, the EU regulations have never taken the danger into account. Not only did the 2008 European directive on arms control ignore the question of disarmed weapons, the European Commission (EC) in 2010 minimised the scope of the problem of what are also called “alarm guns”.

In a report dated July 27th 2010 on the sales of replica firearms, the EC wrote that “reported cases of the illicit conversion of alarm guns and, more generally, the use of replicas with ill intent to intimidate or stage hold-ups must be seen in the context of the relatively high number of alarm guns (or guns which can be used to shoot blanks) in the European Union”. The report demonstrated the EC’s failure to recognise the danger of these weapons, all in the name of the free movement of goods. “Only a few Member States with more restrictive national legislation on replicas sometimes express concerns linked to cross-border movements of replica firearms,” wrote the EC in the report’s conclusions. “In these conditions, there is very little to suggest that European harmonisation of national legislation on replicas would improve the functioning of the internal market by removing barriers to the free movement of goods or by eliminating distortions of competition.” The result is a chronic and dramatic lack of harmonisation of regulations across the continent.

'Abou Omar told me there was no trouble to get arms'

Enlargement : Illustration 4

In the ongoing judicial investigation into the January 2015 terrorist attacks in Paris, the case file includes a document dated September 2013 produced by the firearms department of the Slovak police force’s forensic science service. It presented a graphic explanation (see illustration right) of the dangers with which disarmed weapons - i.e. those that were modified so that they could only fire blanks – can be easily reactivated. In somewhat scratchy English, the introduction to the graphic report says that the business of reactivating neutralized weapons “increasingly happens” in Slovakia but also “other countries of EU”, citing Portugal and the Czech Republic as examples. Indeed, a report by the French police’s forensic science services notes that it was in 2013 that the first reactivated weapons from Slovakia began appearing in France, notably in the Marseille region.

On October 21st 2013, the European Commission published a report entitled “Firearms and the internal security of the EU: protecting citizens and disrupting illegal trafficking”. This time, the Commission appeared to have at last realised the importance of the dangers. “Law enforcement authorities in the EU are concerned that firearms which have been deactivated are being illegally reactivated and sold for criminal purposes, that items such as alarm guns, air weapons and blank-firers are being converted into illegal lethal firearms, and that criminals may very soon exploit 3D printing technologies for assembling home-made weapons or making components to be used for reactivating firearms,” reads the report’s introduction.

But the alarm sounded by the report would result in no legislative changes, and the weapons’ trafficking has continued to prosper from the lack of harmonization of laws of EU member states. Also in 2013, Mediapart met with an arms trafficker specialized in the reactivation of military weapons who said he refused to trade with an institution that deactivated weapons which was based in the town of Saint-Etienne, in south-east France. The reason was that the trafficker’s previous dealings with it showed it applied the strict regulations required in France. “I had loads of changes, invisible to the naked eye, that were carried out,” he said. “They’re virtually impossible to put back into a working [bullet-firing] condition.” But the traffickers have little problem in reactivating weapons bought in Germany or Spain, where the barrels of guns are simply soldered shut. “Some go and buy their weapons in Spain or the former Eastern Bloc countries because their models are easier to re-militarise,” a senior French police source told Mediapart.

Enlargement : Illustration 5

In the summer of 2014, a cache of reactivated weapons from Slovakia – the same as those used by Coulibaly – was discovered in Paris on the sidelines of an investigation into a non-terrorist criminal case. It was around the same period that Coulibaly’s VZ-58 assault rifle was bought over the internet via the website of Slovakian firm AFG Security. The purchase was made by a former French serviceman and far-right militant Claude Hermant, who is based close to the north-east French town of Lille (see Mediapart’s report into his activities here).

Hermant, who is suspected of trafficking in demilitarised weapons, is a paid informer of the French gendarmerie. In a statement given to the judicial investigation into the January 2015 attacks in Paris, he said he had bought and delivered the weapon - among others found after Coulibaly’s death - as part of a covert infiltration operation on behalf of the gendarmerie. It appears that the trace of the VZ-58 quickly disappeared after it was delivered by Hermant to an intermediary, identified only as Samir L., linked to organised crime. It remains uncertain whether Coulibaly subsequently acquired the assault rifle from the intermediary.

Meanwhile, in June 2014 and six months before the January 2015 terrorist attacks in Paris, the European Commission published the results of a study it had commissioned for “an Impact Assessment on a possible initiative related to improving rules on deactivation, destruction and marking procedures of firearms in the EU, as well as on alarm weapons and replicas.” The study’s authors observed: “The evidence collected during the study pointed out several threats that challenge EU citizens’ security and that need to be addressed, and some legal and administrative obstacles related to the effective and efficient implementation of the EU legislative framework. The result is the definition of a set of recommended actions, aimed at strengthening the understanding of rules to be applied to certain types of weapons, such as alarm weapons and replicas, and at promoting the further harmonization and effective implementation of the current legal framework on deactivation and marking of firearms in the EU.”

Enlargement : Illustration 6

One month before that study was published, in May 2014, The European Commission held a meeting of “a group of experts on firearm trafficking”. According to a report on the meeting obtained by European Investigative Collaborations, the enterprise and industry directorate general were forced to admit that the EC directive on firearms control was “based on the principle of minimum harmonisation”.

Yet even after the January 2015 terrorist attacks against Charlie Hebdo magazine and the Hyper Cacher store, there no significant pan-European change to legislation. In Slovakia, however, a new law was introduced on July 1st 2015 which prohibits the purchase of deactivated weapons over the internet. “A declaration is now required following every purchase of a deactivated weapon, and new technical standards have been introduced to limit the possibility of making them function again,” explained Slovak interior ministry spokesman Petar Lazarov.

Jaroslav Naď, an expert on defence issues with the Slovak Security Policy Institute, an independent research body on security and defence policies, believes that the new measures “reduce the risk of these weapons being used for criminal or terrorist activities”. However, two major legislative flaws persist. One is that no form of permit is required to buy a deactivated weapon, only a formal declaration of the purchase is now necessary. The other is that trading of such weapons via the internet is still allowed for transactions between holders of weapons permits or in the case of persons officially authorized to buy and sell weapons and munitions.

It was not until the November 13th 2015 terrorist attacks in Paris, which left 130 dead and more than 350 wounded, for the European Commission to finally envisage a concrete change to legislation.

In a proposed new directive on “the acquisition and posession of weapons”, presented five days after the November massacres in Paris, it is clearly recognised that “definitions should include more specific references to alarm weapons and other types of arms not yet well defined in the EU regulatory framework”. The text added that the “existing Directive does not include alarm, signalling, live-saving [sic] weapons etc. It is proposed to define common criteria concerning "alarm weapons" in order to prevent their convertibility to real firearms”.

“The risk of convertibility of alarm weapons and other types of blank firing weapons to real firearms is high and constitutes a key recommendation resulting from the Directive's evaluation and other study,” the Commission document states. “According to stakeholder information, convertible alarm weapons imported from third countries can enter the EU territory unhindered due to lack of coherent/common rules.” The Commission also finally recognised that “the risk of alarm weapons and other types of blank firing weapons being converted to real firearms is high, and in some of the terrorist acts converted arms were used”.

In a statement issued on the day the new proposed directive was published, European Commission President Jean-Claude Juncker said: “We are proposing stricter controls on sale and registration of firearms, and stronger rules to irrevocably deactivate weapons. We will also come forward with an Action Plan in the near future to tackle illicit arms trafficking. Organised criminals accessing and trading military grade firearms in Europe cannot and will not be tolerated.”

But no legal change has since been voted through and a European Union spokesman questioned by European Investigative Collaborations was incapable of saying when legislation would be introduced.

“There are lobbyists who are putting pressure on European Parliament members to limit the scope of the future directive on weapons by telling them that the control of acquisition of weapons will hassle honest people, that it won’t stop the terrorists,” said a French police officer who is specialised in arms trafficking, speaking on condition his name was withheld. “The holes in the legislation ‘racket’ have, however, been identified for some while.”

Those engaged in terrorist activity have been happy to explain that getting hold of weapons does not present a problem for them. That was the case of Reda Hame, a jihadist who had returned from Syria, in a statement he gave last August to the French internal security service, the DGSI. “To find weapons, Abou Omar told me that there was no trouble to be supplied with arms and material,” he said. “I only had to ask for what I needed, in France or in Europe. In my opinion, they have networks.”

‘Abou Omar’, referred to by Hame, was the pseudonym used by Abdelhamid Abaaoud, the Belgian-Moroccan Islamic State group militant who coordinated the November 13th attacks in Paris.

-------------------------

- The French version of this article can be found here.

English version by Graham Tearse