At the end of the 1990s, Danish pharmaceutical company Lundbeck faced a serious problem. The patent on its antidepressant drug citalopram would expire in 2003 when it would become a cheaper generic product and which would lead to colossal losses for Lundbeck.

Citalopram was marketed under various brand names across the world: as Seropram in France and much of Europe, as Cipramil in the UK and as Celexa in the US.

Lundbeck therefore planned the launch of a new patented antidepressant, one that would be derived from citalopram but which must be convincingly accepted by medical professionals and health authorities as more effective. In the event, this was escitalopram, sold as Seroplex in France, Cipralex in the UK and as Lexapro in the US.

Enlargement : Illustration 1

With the help of internal documents and witness accounts from former Lundbeck employees and French regulatory committees, Mediapart has been able to establish the history of the controversial drug that allowed the firm, through secret links with official health watchdogs, intense lobbying, the help of allies within ministries and hidden price-fixing agreements, to achieve a turnover for escitalopram in France of more than 1 billion euros over ten years.

Back in the 1990s, US pharmaceuticals company Forest, which had developed citalopram with Lundbeck, suggested to its Danish partner that, in face of the imminent arrival of generic products, a ‘mirror’ drug should be produced.

But Lundbeck began working on an antipsychotic, called sertindol, which finally failed to receive approval from the US Food and Drug Administration, and was withdrawn from European markets in 1998 after it was found to carry a risk of causing sudden death and cardiac arrhythmia.

The flop left Lundbeck withfew other new projects, reviving the idea of launching an ersatz of citalopram. This would be called escitalopram, and Lundbeck would have to engage in a massive campaign to convince the authorities and medical profession of the new benefits of the drug.

In the meantime, a number of pharmaceutical companies in different countries had already begun preparing generics. It was naturally in Lundbeck’s interest that the generic alternative to citalopram should arrive on the market later than sooner, allowing its own branded citalopram a longer life while development of escitalopram continued.

It was German pharmaceutical company Tiefenbacher which had at the time advanced the most of any in developing a generic alternative, and Lundbeck decided to buy-up Tiefenbacher’s Italian subsidiary VIS Farmaceutici, based in Padua, in order to block its marketing. It then led a legal and financial campaign to dissuade other firms from developing generic competitors to its antidepressant blockbuster. In 2010, the European Commission (EC) launched action against Lundbeck for delaying the arrival of a generic alternative to its ageing antidepressant, and in 2013, ten years after the events, it handed the Danish firm a 93.8 million-euro fine for its obstruction (several other pharmaceutical companies were also fined lesser amounts for similar behaviour).

"It is unacceptable that a company pays off its competitors to stay out of its market and delay the entry of cheaper medicines,” said EC Vice-President Joaquín Almunia, in charge of competition policy, when the fine was announced. “Agreements of this type directly harm patients and national health systems, which are already under tight budgetary constraints.”

Lundbeck appealed against the EC sanction and the case is still unresolved. Whatever the final result, the fact remains that the Danish firm succeeded in delaying a generic alternative to its money-spinning drug at the end of its patent.

In 2002, Lundbeck’s new antidepressant escitalopram was given the all clear by the French committee that decides market approval for new drugs, the Commission d’Autorisation de Mise sur le Marché (CAMM), and it was set to launch in the country under the brand name Seroplex. But an all-important issue then for Lundbeck was the decision that would subsequently be taken by the Commission de la Transparence (Transparency Commission), the official scientific board, made up of medical experts, which decides what proportion -if any - of the purchase price of a newly-authorised drug is refunded to patients by the French social security system.

If the Commission decides that a new drug offers no new improvement for healthcare, the drug will be sold at the same price as a generic. If that were the case for Seroplex, it would naturally represent a total failure for Lundbeck, whose previous antidepressant, citalopram, marketed in France as Seropram, was now about to be manufactured as a generic. If, however, the Commission decides the drug presents even only a minor improvement, its over-the-counter price will be partly refunded by the social security system. That allows for a higher sales price and almost guaranteed marketing success.

A former Lundbeck manager, who spoke on condition that his name was withheld, told Mediapart that the new drug, Seroplex, was “in reality a colour copy of the preceding one”, adding that “never did any study show that Seroplex brought any kind of improvement on Seropram”.

The former head of Lundbeck’s French subsidiary, Jacques Bedoret, was hardly more reassuring. “There was no certainty that Seroplex contained an advantage with regard to Seropram,” he said.

In December 2002, Lundbeck was officially informed by the Transparency Commission that its submission for Seroplex to be classified among medicines refunded to patients by the social security system would be rejected. When the Commission makes such a move, it is then up to the pharmaceutical company concerned to decide either to withdraw its application completely, or to re-present it with further information, such as complimentary studies and research on the effectiveness of its drug. In May 2003, Lundbeck told the Commission that it would submit a new application, which it delivered in June 2004. But once again, the commission decided Seroplex represented no improvement on existing drugs.

This left Lundbeck with the option of beginning an appeal procedure. As Mediapart revealed in March in an article on how regulatory experts were moonlighting for drugs firms (and which prompted the opening of a judicial investigation), the firm was in contact with rheumatologist Renée-Liliane Dreiser, an expert advisor to both the Transparency Commission and the drugs approval body, the CAMM. Doctor Dreiser is at the centre of a small group of influential mutual friends: Gilles Bouvenot, vice-president of the CAMM between 1999 and 2003, and president of the Transparency Committee from 2003 to 2014: Bernard Avouac, president of the Transparency Commission from 1989 to1998: Jean-Pierre Reynier CAMM vice-president from 1994 to 2002 and Christian Jacquot, a member of the CAMM board from 1996 to 2012.

This group of health watchdog members were paid by Lundbeck to advise it on how Seroplex might be given the status of a drug whose purchase price is refunded by the French social security system and they held two discreet meetings altogether, just months apart, in Marseille.

Bouvenot, president of the Transparency Committee from 2003 to 2014, has denied attending such meetings and denied secretly meeting Lundbeck representatives. He said he would save any comments on the matter for the judicial investigation launched after Mediapart’s revelations in March. However, Mediapart has established that he did meet Lundbeck president and CEO Claus Baestrup in discreet circumstances at the Sainte-Marguerite hospital in Marseille. Questioned by Mediapart, Braestrup, who was head of the firm between 2003 and 2008, said he could not remember “the precise reasons for the meeting” because, he said, the two men had held many such encounters.

Neither Avouac, (Transparency Commission president from 1989 to 1998), nor Reynier, (vice-president of the CAMM from 1994-2002), answered Mediapart’s request for an interview about the meetings in Marseille. Jacquot, a member of the CAMM board from 1996-2012), told Mediapart he could not remember the Marseille meetings.

Lundbeck's ally at the health ministry

Lundbeck went about lobbying all of the more than 20 members of the Transparency Commission. The lobbysists hired by the company included Jacques Biyot, now head of the prestigious higher education institution, the Ecole Polytechnique. Another was the psychiatrist and academic Édouard Zarifian, who died in 2007, and who was notably known for having written a report for the French health ministry in 1996 which was critical of the overconsumption of psychotropic drugs, notably antidepressants.

In February 2004, the director of medical affairs at Lundbeck’s French arm sent out an email that contained a document with details of forthcoming meetings with Transparency Commission members. Contacted by Mediapart, she insisted that she had no knowledge of the email and suggested that her email account must have been hacked, adding: “Clearly, I served as a postbox.”

The document attached to the email (see below) illustrated the intensive lobbying with which the Danish firm targeted all the members of the Transparency Commission. Written in English, it contained details of when the firm would meet with each member and set out the strategy of approaching them. Alongside the names of some members were comments on their profiles.

One Commission member, psychiatrist Michel Petit, is described as “known to be unfavourable and stiff & generally unfavourable to industry & contributed heavily to previous negative rulings”. The note advised that he be approached through a “Specific channel”.

Also mentioned in the document was François Lhoste, who represented the economy ministry on the body that fixes the prices of medicines, the CEPS. He was described as “a friend”. Earlier this month Lhoste was removed from his position on the CEPS after Mediapart revealed how he moonlighted as an advisor to French pharmaceuticals company Servier, which notoriously marketed a diabetes drug as a weight-loss product despite its known dangers, causing an estimated 2,000 deaths from cardiac valve damage.

A member of the Transparency Commission, who asked his name to be withheld, told Mediapart that Lundbeck sent Danish statisticians to meet him and convince him that the new antidepressant, Seroplex, was particularly effective for severely depressed patients. The medical professional admitted that they succeeded in winning him over to the argument. “I was taken for a ride,” he said. “Today I regret that choice. I was wrong.” He added that Gilles Bouvenot, the Transparency Commission president was also able to influence the voting. “We said to ourselves we know how we’re supposed to vote”, he said.

The source also spoke of a phone call he received from a member of then-French health minister Philippe Douste-Blazy’s senior staff, Olivier Blin. He said he was told by Blin that the French foreign ministry hoped for a favourable decision for “this medicine made by a small Danish pharmaceutical firm in difficulty”. The source said he was peturbed by the conversation. “A call from the ministry, it means something,” he said. “It’s an authority all the same.”

During this period, Olivier Blin made a lot of calls. According to several members of Doust-Blazy’s ministerial inner cabinet, and also former senior employees of Lundbeck, he put a lot of energy into promoting Seroplex.

Yet Blin, a clinical pharmacologist, had no ministerial brief to involve himself with administrative procedures concerning the approval and evaluation of new drugs. Indeed, the Transparency Commission was created specifically to bar political influence from the matter.

Doust-Blazy’s inner cabinet also included Claude Griscelli, who at the time was a moonlighting advisor to pharmaceutical firms, and Émilie Schällebaum, the minister’s deputy chief-of-staff in charge of relations with parliament, who now works for Lundbeck as its director of communications and public affairs.

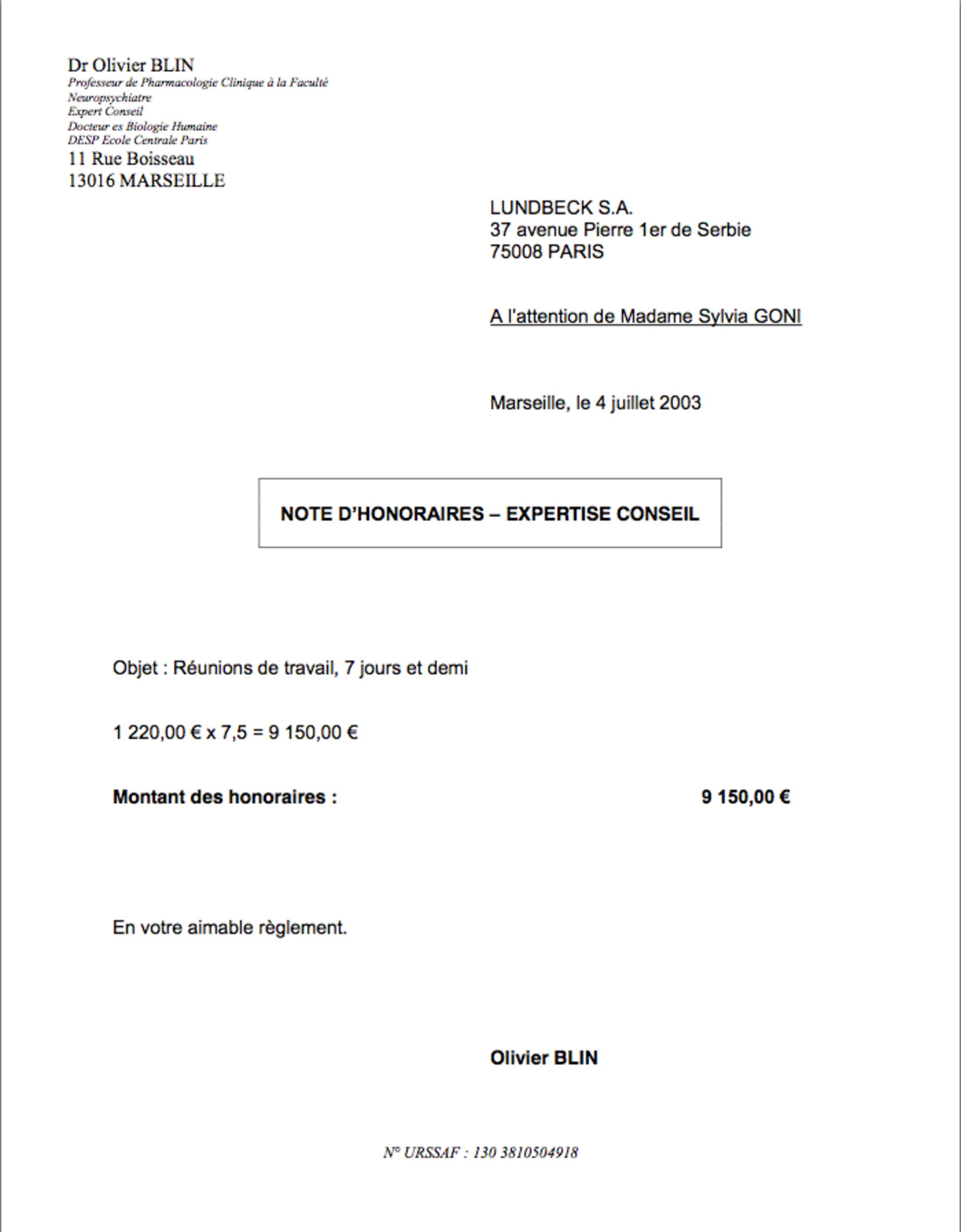

In 2003, just months before joining the health ministry, Olivier Blin, who now works as head of clinical pharmacology and pharma security at the Timone Hospital in Marseille, was commissioned by Lundbeck for a series of studies, including one (see below) which involved Seroplex.

Mediapart has had access to internal documents from Lundbeck which include invoices for his work for the Danish firm (see example below).

Enlargement : Illustration 5

Blin continued to work for Lundbeck after he left the health ministry, where he worked for one year, and which included the writing of scientific articles. Blin told Mediapart he no longer remembers this. “I did not receive a cheque for what I did at the ministry,” he told Mediapart.

“It’s true that I met at least three times with members of Lundbeck at the ministry,” Blin said. “But I never attempted to influence members of the Transparency Commission.” Asked why, in that case, did he on several occasions meet with representatives of the Danish firm, he answered: “I told them that in my opinion, their dossier justified a re-examination, but things stop there. For me, the technical dossier showed up elements that led one to think that this medicine was superior to the preceding one."

"The worst thing is to be dependent upon one pharmaceutical firm," he added. "Now, I never worked with only one laboratory, and everything that I did I always declared.”

Enlargement : Illustration 6

Philippe Douste-Blazy, who began his career as a cardiologist, is now an Under-Secretary-General of the United Nations, where he has the post of special advisor to the UN Secretary-General on innovative finance for development. Mediapart asked him if he had been involved in promoting Lundbeck’s drug while he was health minister. “Lund what? What nationality is this pharmaceutical firm?" he asked in a surprising display of ignorance regarding the pharmaceutical company.

"I heard about Seroplex for the first time in 2009 or 2010, for a member of my family. I never intervened for this medicine and I never asked anyone to intervene. I didn’t know that Olivier Blin had worked for this pharmaceutical firm.”

Asked to comment on Blin’s meetings with the Danish firm, as well as with others, Douste-Blazy said: “It’s completely abnormal. A [ministerial] cabinet must never meet the firms. It’s truly shameful. At the time, nobody told me anything [about this].”

Winning favours in exchange for industrial plant

In May 2004, the French medical review Prescrire, considered a reference in its field because of its established independence, carried a report on Seroplex in which it argued that the new antidepressant “has no demonstrated advantage” over its predecessor Seropram.

However, in December 2004, the Transparency Commission finally overturned its initial rejection of Seroplex as a refundable drug. Classifying it as an 'ASMR 4', the lowest category of effective new drugs which represent an improvement on existing ones, it agreed that 65% of the over-the-counter price of Seroplex should be refunded by the French social security system in cases where patients suffered “major depressive episodes”. While the purchase price was yet to be established, Seroplex had now past all the main hurdles and the drug was eventually launched on the market in 2005.

Defining the purchase price of a medecine is the remit of the CEPS (Comité économique des produits de santé). Its president, Noël Renaudin, recalled that the approach of the CEPS was always to fix a price similar to comparable medicines on the market. Lundbeck was seeking the highest possible purchase price, not only because of its potential returns in France, which was then the largest market for antidepressants, but also with regard top the fact that many other countries would base their own approval of the price of the drug on the French decision.

A confidential deal was mapped out between the CEPS and Lundbeck under which the latter would be awarded a relatively high over-the-counter price for Seroplex, in return for which the firm would, over a period of three years, pay back a part of its profits from the drug to the social security system. Mediapart has gained access to the document that cemented that deal (see below). In it, estimations were made of how much would be sold, and at what dosages. It allowed for the imposition of a cut in the price of the drug if, after three years, larger volumes of Seroplex were sold than were forecast. The details were never made public.

Noël Renaudin defended the deal, one of several of the same type concluded during his presidency of the CEPS between 1999 and 2011. “In a second phase we recover the money,” he told Mediapart. “So for us, it’s not a problem, and for the firms the face value is extremely important for the parallel sales. If the price is lower than in Germany, the German bulk-buyers will come to France for supplies, and the parent company won’t be happy. So we find an arrangement […] There was a threat that Lundbeck would sacrifice the French market. Now, at the time Seroplex seemed to us to be a quite interesting product. When you are on the demand side, you look for an arrangement.”

Renaudin also defended the confidentiality of a deal which engaged the French public administration. “Firms don’t want the conventions made public,” he said. “If it was not confidential, nothing more would be possible. It’s like the deliberations at the CEPS. If the deliberations were made public, the members would adopt stances. It would be difficult to reach a consensus.”

But such practices have a heavy cost for the French top-up medical insurance companies (which, according to their offer, pay all or part of the cost of medical treatment remaining after the percentage that is refunded by the social security system), for those many French patients who don’t have such insurance, and for patients in poorer countries, such as Romania or Bulgaria, where the market price of a drug has been aligned to that agreed in France.

By 2007, according to documents seen by Mediapart, the amount Lundbeck paid back to the social security system under the terms of the deal totalled 2 million euros per year. It was also in 2007 that the CEPS demanded that Lundbeck reduce the price of Seroplex, which prompted a new round of negotiations.

At the time, Marie-Laure Pochon had succeeded Jacques Bedoret as head of the Danish firm’s French arm. She commissioned Aquilino Morelle as the firm’s lobbyist with regard to the CEPS members. Morelle, who went on to become a special policy advisor to President François Hollande, was at the time an inspector with France's public service inspectorate, the Inspection générale des affaires sociales (IGAS). He was forced to stand down from his role as presidential advisor after Mediapart last year revealed the conflict of interest between his post at IGAS and the consultancy work he simultaneously carried out for Lundbeck. He was paid 12,500 euros by the firm for placing at its disposition his network of contacts and his own influence.

IGAS has still not announced what, if any, sanctions will be taken against Morelle. A judicial investigation into the affair was closed after it found that he had not committed a criminal offence.

At the end of 2007, Marie-Laure Pochon pledged that Lundbeck would invest in a manufacturing plant in France by buying up its long-term partner in the country, Elaiapharm, based at Sophia-Antipolis, close to Nice. Lundbeck had already raised this possibility during its lobbying for Seroplex in 2004, but the project was later shelved after it had achieved its aim. But Pochon promised that this time the project would go through. In the event, the CEPS agreed the new over-the-counter price for Seroplex which Lunbeck was seeking. “A minister would not have understood that I don’t take the industrial stakes into account,” said Noël Renaudin, who admitted asking the CEPS members to show leniency towards Lundbeck because of the investment pledge.

The new Lundbeck production plant in France opened at Sophia-Antipolis on December 4th 2009, in a ceremony attended by then-industry minister and conservative Member of Parliament for the local constituency, Christian Estrosi. Several months later, Marie-Laure Pochon was given the Légion d’honneur, France’s highest award for civil merit.

At the time, Seroplex was among the ten medicines whose over-the-counter price was most-refunded by the French social security system. Official figures published by the French social security system, and which run up until 2013, show that the turnover for Seroplex since its launch reached 1 billion euros. Meanwhile, the French social security system has paid out 700 million euros in refunds to patients of the purchase price.

The Transparency Commission reviews its decisions on drugs every five years after they were first taken, and in 2013 it reduced Seroplex from category 'ASMR 4', the lowest category of drugs which offer an improvement over others in the same field, to category 'ASMR 5', meaning it offers no improvement at all above other existing antidepressants (see more here). It justified the move - which is a relatively rare one - by the results of a British study which found that the previously claimed advantages of Lundbek’s antidepressant were exagerated and it was in fact of little especial interest for patients.

The patent for Seroplex finally expired in 2014, when escitalopram could be produced as a generic. In preparation for this the Danish firm had developed another antidepressant, called Brintellix. In February this year, the Transparency Commission decided that the drug was not eligible for classification as a medicine whose over-the-counter price is in part refunded by the social security system.

Lundbeck declined Mediapart's invitation to comment on the issues raised in this article.

-------------------------

- The French version of this article can be found here.

English version (abridged) by Graham Tearse