On Wednesday, December 15th, while the European Trade Union Confederation called for a continent-wide day of action against austerity measures, violent clashes against budget cuts shook the Greek capital Athens. As the rating agency Moody's announced it might downgrade Spain's credit rating, causing the euro to fall, Ireland was adopting its fourth austerity plan in three years.

"In the spring of 2010, fiscal austerity became fashionable," were the disenchanted words of the American Nobel prize winner for economics Paul Krugman on October 21st, following the vast austerity plan unveiled in the United Kingdom. They are the regrets of a confirmed Keynesian, all too aware that the old orthodox economic dogmas are back. After a period of economic stimulus, the moment comes when bills have to be paid.

The sovereign debt crisis in Europe has sparked a mad dash to reduce public spending deficits. To satisfy both the credit rating agencies and investors first Greece, then Ireland, adopted austerity plans of historic proportions. As one, the whole of the euro zone, including France, has adopted the idea of budget cuts. But just what do these billions of euros in savings actually represent? Here, Mediapart's Mathieu Magnaudeix takes a closer look at the figures announced, and examines whether governments had other choices available - and whether the cuts might in fact end up destroying economic growth.

400 billion euros of austerity measures in Europe

A study published in October by the French bank Société Générale estimated that the total amount of spending cuts announced among Europe's national economies, staggered over several years, totalled "more than 350 billion euros". That was before the Irish plan presented at the end of November envisaging some 15 billion euros in cuts. So the total is now close to 400 billion euros all told. It's a considerable sum, but one which in isolation doesn't mean much. To gauge its importance it must be measured against each country's gross domestic product (GDP).

Greece and Ireland are the champions of austerity measures. The first to start the movement at the beginning of 2010 was Greece, which has come up with four successive programmes of tax increases (on VAT, tobacco, alcohol, petrol and the wealthy) and then a huge programme of cuts over three years. This included measures on VAT and fuel again, plus removing annual bonus payments for civil servants and pensioners1. The total is 35 billion euros in savings over three years, the equivalent of 17% of the country's annual GDP.

-------------------------

1: In Greece, civil servants and pensioners have traditionally received two extra months salary or pension a year - known as 13th and 14th month payments - as bonuses.

Ireland is now engaged in its third plan in three years. "Thirty billion euros of savings are planned between 2008 and 2014," estimates Céline Antonin of the French academic economic research centre, the Observatoire français des conjonctures économiques (OFCE). That is 13% of one year's GDP. For both countries these are bitter pills to swallow.

Among the larger nations, the United Kingdom (UK) is the one that has carried out the biggest budgetary blood-letting in terms of GDP; 130 billion euros between now and 2015 (9% of GDP). Then comes Portugal (11 billion over four years, 7%), Spain (50 billion between now and 2013, 5%), Germany (80 billion euros, 4%) and Italy (24 billion over three years, 2%). There is also France which has announced 110 billion euros in savings between now and 2013 (6% of GDP) but which remains imprecise over exactly how it plans to achieve that.

Beyond the figures, all these economic plans seem to have been inspired by the same economic software. Rises in direct taxes are sometimes planned (as in Greece, Italy or France, with a minimal rise in tax on stock options and on the upper rate income tax bracket). However, for the most part "austerity [measures] hit households", says Céline Antonin. A stark illustration of this is in Ireland where the minimum wage has gone down by one euro per hour worked.

An increase in the VAT rate appears almost a requirement of the austerity plans. It has gone up twice this year in Greece and in Portugal, and has been raised in Ireland, the United Kingdom and Spain. This is a measure that is both unfair and risky; though it is paid by everyone it hits the hardest all those on modest incomes, who save little and spend a great deal.

The European Trade Union Confederation, in a recent document on austerity measures, says that beyond public deficit cuts, they are "also about 'disciplining' wages" in that they "weaken collective bargaining systems". In a series of themed documents, the ETUC details the measures that encourage employers to opt out of collective-bargaining agreements in Greece and Spain, and the constant refusal of France to raise its minimum wage.

Cuts in the public sector - an "easy target", says the ETU - are also popular with governments. Public-sector salaries have been frozen or reduced in Greece, Italy, Portugal, France, Ireland, Bulgaria, Poland, Romania, Estonia and Lithuania, with cuts of up to 50% in Latvia. Jobs are going too; 34,000 are planned to be axed in France in 2011, adding to the 100,000 already gone since 2007; 330,000 in the UK, 250,000 in Romania, 25,000 in Ireland and 15,000 in Germany. The measures are even more radical in the UK; all ministries have to cut their budgets by 25%, and local authority funding has been cut back drastically.

Finally, social benefits and the mechanisms for redistributing wealth have been called into question. The UK is cutting back on benefits for families, housing, schools and the disabled. Germany is lowering payments for the long-term unemployed. Spain is targeting payments for elderly dependants and is freezing pensions - as is Greece. The legal age of retirement has been increased in France, Italy, the United Kingdom and Spain.

Though the banks were at the origin of the financial crisis, they have largely been spared by the austerity measures, apart from taxes announced in France, the UK and Germany. In Ireland the situation is especially striking; if the Irish state had not had to bail out its over-extended banks it would have posted a deficit of just 11% of its GDP, in contrast with the current 32% .

Businesses have escaped the austerity measures too. "The general will is to favour competitiveness and exports," says Céline Antonin. Ireland - where the low tax rate of 12.5% has not been increased - the UK and Portugal are openly gambling on an uncertain return of growth to relaunch the economy.

"Everyone is betting on a recovery of growth through demand from the private sector at the expense of demand in the public sector," says Sylvain Broyer, an economist at investment bank Natixis. The chapter of Keynesian-ism is well and truly closed. But it is a risky gamble, as European economies are closely entwined and none can mount a recover on the backs of others.

Why this wave of austerity?

The well-established background is that the financial crisis of 2008 caused the financial system to falter. Countries opted to save the banks, taking the view that their collapse would cause more damage. Lower revenues were raised by countries because of reduced economic activity. Subsequently, state intervention to save the banks, followed by recovery spending plans, only increased deficits and debts. At the start of 2010, the situation of Greece lit the fuse. "The public guarantees given to the banks were not tenable," explains Sylvain Broyer. "It was a powder keg and it just needed the Greek spark to set fire to the lot."

With the European states slow to react, the institutional fault-lines of the euro zone revealed themselves. The game in which the markets wreaked havoc over the sovereign debts of the weakest nations (Ireland, and perhaps tomorrow Portugal or Spain) could begin. European countries were afraid, fearing a domino effect. Meanwhile the international institutions, with the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) at the forefront, were pushing for "budgetary stabilisation". Agreed in urgent circumstances, the Greek and Irish plans negotiated by the EU and the IMF (International Monetary Fund) were particularly drastic.

Could things have been done differently? European leaders argue there was no choice. Yet, so far, US President Barack Obama has continued to stimulate the economy while the country's Federal Reserve System is busily buying up debt. The reason for this is the haunting memory of 1937: after the New Deal of President Roosevelt, the abrupt stopping of stimulus measures hit economic activity and unemployment sharply increased in 1938.

Europe, meanwhile, is keeping with its usual budgetary orthodoxy, as promoted by the European Commission. The European Central Bank (ECB) only intervenes in extreme emergencies.

For a year now, and influenced in particular by the works of the former IMF chief economist Kenneth Rogoff, the dominant belief in the markets is that an economy's future growth is put in danger at or above a debt ratio equivalent to 90% of GDP. According to a European Commission forecast in September, this ratio "will progress from 79% to 89% in the EU between 2009 and 2011."

To reduce debt there are four solutions. One is inflation; this scenario has been ruled out as the ECB refuses to print money. A second is default; there again this has been excluded - for the time being - because it would put the euro in danger. Number three is growth, but that is very weak, apart from in Germany. That just leaves number four - austerity.

But a mystery still remains: why has Europe decided to act so drastically, at the risk of causing outrage among public opinion?

The answer lies in a re-read of the economic texts that Krugman says have become "fashionable". For the past year several high-profile studies - drawing on economic orthodoxy as if the crisis had changed nothing - have explained that austerity measures can create economic activity.

These studies, written by Alberto Alesina, an Italian economist at Harvard University, experts at the British Treasury and others at the ECB, share broadly common conclusions. Using the examples of Sweden and Canada in the 1990s to support them, they advocate massive and prolonged austerity plans, of major reductions in public spending rather than rises in taxes and, if possible, significant cuts in social benefits. "This theory is what you hear just about everywhere at the moment in European institutions," explains Sylvain Broyer. In fact these are the intellectual foundation of the austerity plans in Europe which are carbon copies of texts that, although they may not seem to, rehabilitate traditional economic theory.

Austerity is heading for disaster, warns French bank Société Générale

The problem is that the past examples cited above have their limitations. In the 1990s, Canada and Sweden benefited from high interest rates and so could cut them, and they devalued their currency - an option that is impossible for the euro. Above all, EU countries, which have engaged in concerted austerity measures, represent together 21% of the world's GDP, and there is potential to stall growth completely. Indeed, the IMF has recently begun shyly distancing itself from the dogma of austerity.

"Austerity will slow down the revival of growth," explains Céline Antonin of the OFCE. "External demand will fall because austerity is happening all across Europe. As for internal consumption, it is doubly slowed down by the measures hitting households and the drastic reduction in public spending." The OFCE has calculated that in 2011 these measures will remove 2.6% of growth in Portugal, 1.9% in Spain, 1.4% in France, 1.1% in Germany and 4.4% in Greece.

In France, a group of economists who have formed the "Appalled Economists" association, are protesting against this striking return to what they call "neo-liberalism" and the "dictatorship of the markets", and are calling for a large-scale, democratic European debate on the matter.

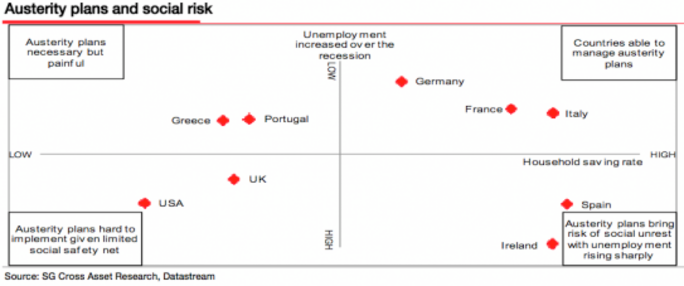

The Keynesians are not the only ones sounding the alarm bell. The French bank Société Générale has analysed the risk of the austerity measures for its investor clients in a report entitled 'All you ever wanted to know about European austerity plans (but were afraid to ask)'. It considers that some of the plans that have been announced are hurtling straight for disaster.

According to this study -available only to the bank's clients but of which extracts are available on the internet (e.g. here) - the measures risk being painful in Greece and in Portugal where the level of savings is low and households have few reserves to fall back on. It is the same story in Ireland and in Spain, where the property markets remain depressed. "The austerity plans are going to provoke a risk of social unrest and unemployment is going to rise rapidly," says economist Daniel Fermon, the study's author.

In the UK, he warns, the welfare state has already been so hammered that the social safety nets risk not being able to absorb the shock. Only Germany, France and Italy, he predicts, appear capable of managing the effects of such measures. But even in those three countries, that view must be regarded with caution because the measures will very harshly affect entire minority groups in society.

"The same formulas have been applied everywhere," laments Céline Antonin. "But we have failed to tackle the structural reasons for the deficits [which are] tax evasion in Greece, low competitiveness in Portugal, the macrocephaly of the banking system in Ireland, the property bubble in Spain."

-------------------------

English version: Michael Streeter