Malta, the tiny Mediterranean island state with a population of about 430,000, is one of the lesser-known tax havens within the European Union. Yet each year, its generous corporation tax deprives other countries, and notably other EU member states, of an estimated 2 billion euros in fiscal revenues.

For almost four months, 49 journalists from 13 media organisations, including Mediapart, have been involved in a joint investigation, under the umbrella of the European Investigative Collaborations (EIC) journalistic collective, into some 150,000 confidential documents which reveal the extent of the tax avoidance, money laundering and corruption that thrives on Malta’s secretive offshore financial structures.

The results of those investigations will be published over the next two weeks by Mediapart and its EIC partners in a series entitled the Malta Files.

The Malta Files are based on two sources of information. One, obtained by German weekly Der Spiegel, consists of thousands of confidential documents including emails, contracts, and accountancy files from a Maltese trust company specialised in company registrations and administration. The second is an Excel spreadsheet, obtained by online investigative magazine The Black Sea, into which is listed all the information filed with the Maltese companies registration office at the date of September 20th 2016, and which concerns 53, 247 firms.

While the company registration office can be accessed by the public, it is impossible to carry out a search of personal names. The EIC, using the spreadsheet, has been able to research the list of the 77,818 people and firms which act as directors or shareholders of Maltese-registered companies, including 1,291 French nationals (but excluding those who are hidden behind frontmen).

The list includes the directors and heads of major companies and multinationals (such as Bouygues, Total, BASF, Ikea), banks such as Reyl and JP Morgan, a famous actor, the founders of a large luxury goods firm, the family of one country’s head-of-state, Isabella dos Santos - the daughter of Angolan president José Eduardo dos Santos, and an Azerbaijan state oil company. Along with these are numerous lesser known individuals, including small businessmen and consultants, dancers and horse-breeders.

Of course, not all those listed are involved in tax fraud. Some appear on the list because they live and work in Malta, while others do business or optimise their tax liabilities in all legality.

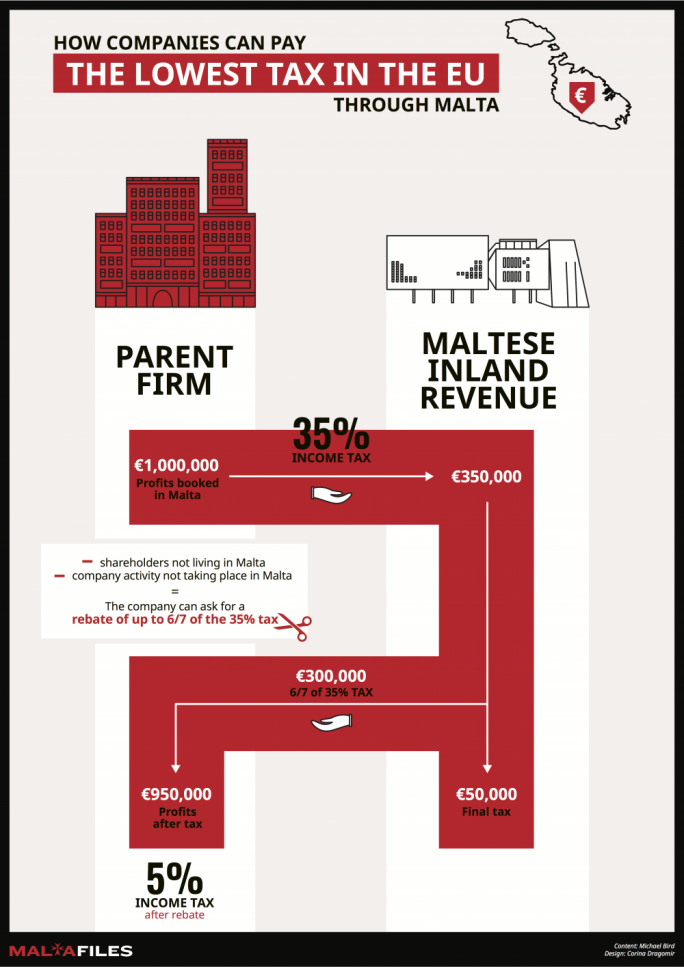

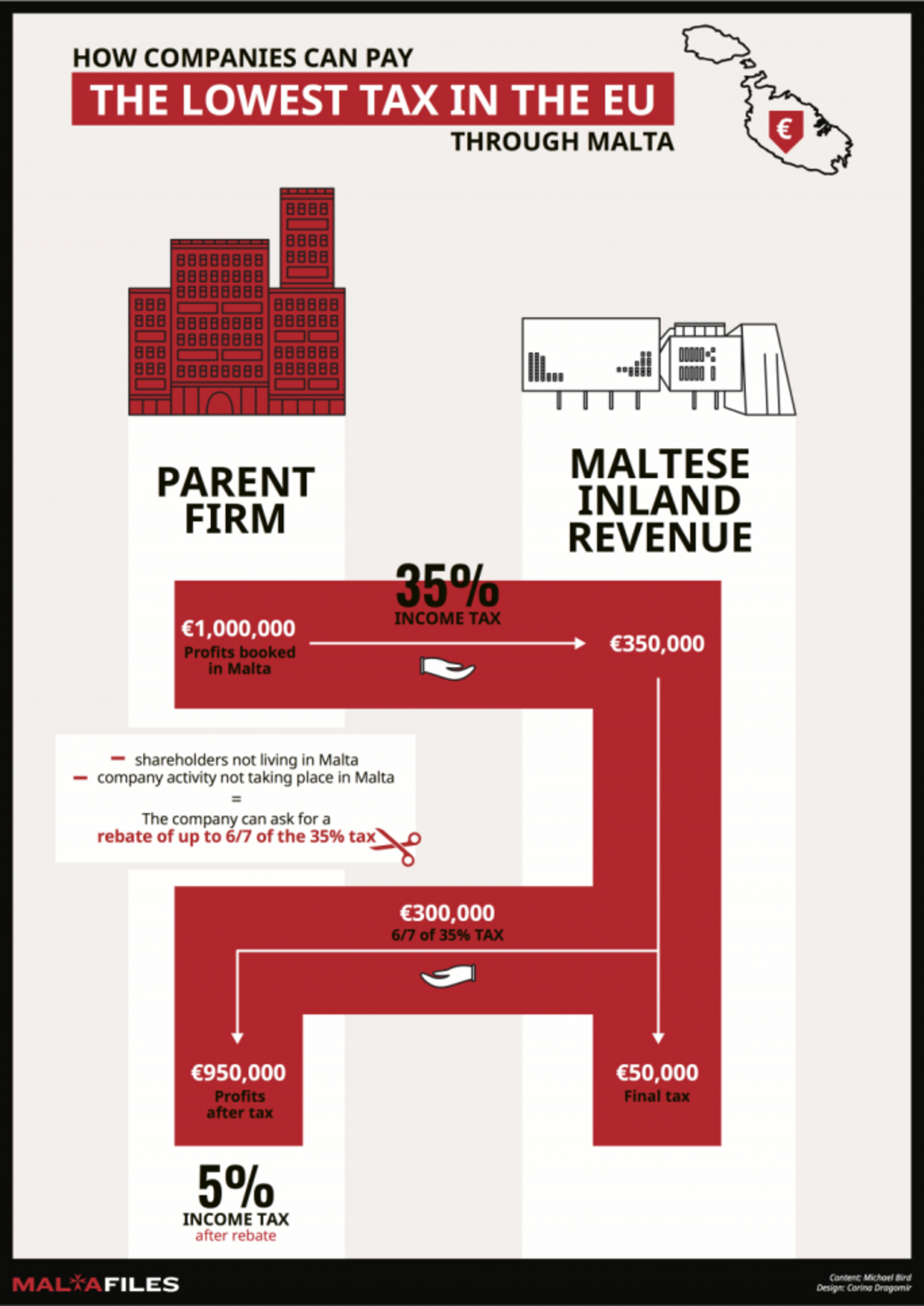

Enlargement : Illustration 2

On May 10th, Norbert Walter-Borjans, the finance minister of the German state (Land) of North Rhine-Westphalia announced in a press release that, through an anonymous source, he had obtained a list of companies registered in Malta and that, "the data reveals how corporations and private persons on the Mediterranean island use company braids to bypass tax in Germany in a big way". The list is the same as that obtained by the EIC.

"This is partially done with legal tricks,” continued Walter-Borjans, “but often also by means of offshore companies, which serve exclusively as tax evasion constructions."

The minister added that he would share the information about what he called "the Panama of Europe" with other countries, which in all logic should include France.

Malta’s finance minister Edward Scicluna took to Twitter in an immediate reaction to Walter-Borjans statement: "Pull another one," he wrote. "Since when the whole Maltese company register of Maltese registered [sic] companies becomes foreign, offshore and German?" Scicluna denied that Malta was in effect a tax haven and claimed the German regional finance minister had exaggerated the importance of the list of companies for political reasons.

Enlargement : Illustration 3

A study published last year by the British NGO Oxfam, in part based on the criteria of a European Commission report on “Structures of Aggressive Tax Planning and Indicators”, identified Malta as being in fourth position among EU member states offering businesses a haven for corporation tax. It came behind the Netherlands, Belgium and Cyprus, but ahead of jointly fifth-placed Luxembourg, Latvia and Hungary.

An investigation published last September by EIC media partner Malta Today reported that every year “up to 2 billion euros that is taxed using Malta's highest rate on on profits generated outside of the island, are wiped clean off the slate by the Maltese taxman so that a ‘trickle’ of 200 million euros in tax receipts is retained in Malta”. The report said that the situation had escalated since 2006, when the write-off was ten times less, meaning that in less than ten years “close to 9.7 billion euros in tax that could have been paid in other countries was wiped off”.

“Malta’s tax refund scheme helps foreign companies and shareholders to avoid paying their fair share of tax where they do business,” said Oxfam’s tax policy expert Susanna Ruiz in an interview with the paper. “These types of aggressive tax planning schemes deprive other countries of valuable tax revenues which they need to pay for vital public services such as healthcare and education.”

Published in January, just as Malta began its six-month term heading the rotating presidency of the EU, a report commissioned by the Green bloc of Members of the European Parliament (MEPs) estimated that, between 2012 and 2015, Malta had helped multinationals to avoid paying 14 billion euros in taxes to other countries.

Malta in fact applies the lowest tax rate on profits of foreign-owned companies than any other country in Europe. The rate is officially 35% (just more than the 33.3% rate applied in France), but a foreign-owned company that pays its shareholders dividends is granted a rebate on its taxes of 85%, resulting in an effective tax rate on foreign earnings of just 5% for offshore companies, lower than Bulgaria (10%) and Ireland (12.5%). This most certainly explains the vast number of so-called “letter-box” companies domiciled on the Mediterranean island state, where the assets of banks and 581 investment funds represent 789% of its Gross Domestic Product (GDP).

Informal alliance of EU tax havens

Malta offers other attractive tax rates, like that applied to owners of boats and planes registered on the island, revenue from trademarks, and profits for gaming firms. The taxes applied to boat owners allows them to escape VAT and to reduce the social charges liable on crew salaries, even if the boats – such as luxury yachts – are generally moored elsewhere than Malta.

“Malta is not only a tax haven,” commented Fabio de Masi, a German MEP with The Left party, part of the European United Left-Nordic Green Left bloc in the European parliament, in an interview with Malta Today. “But experience tells us that the imputation scheme with a generous tax refund is the perfect tool to also launder criminal money.” The truth of that affirmation is illustrated by the evidence that emerges in the Malta Files, even if the confidential documents accessed by the EIC only concern one of the around 30 trust companies operating in Malta.

These tax advisors and suppliers of turnkey company structures have no scruples in ensuring the secrecy of their clients. For a fee of several thousand euros per year, they supply frontmen who play the role of straw directors and shareholders. The most cautious clients can further increase their protection by creating a trust registered in Malta.

Enlargement : Illustration 4

Many of these trust companies were named and shamed in the Panama Papers revelations which detailed how they supplied offshore company structures based in the Central American tax haven. Following the Panama Papers scandal, the European parliament set up a committee to investigate if and where European law had been infringed. The cross-party “committee of enquiry into money laundering, tax avoidance and tax evasion”, called PANA, visited Malta in February to further its investigations. In its subsequent report it detailed the results of its interview with Maltese finance minister Edward Scicluna who, it noted, contested that Malta was a tax haven. “On the question on the reason of the high number of Maltese intermediaries involved in the Panama Papers, he [Scicluna] replied that it is not illegal to give advice,” the report said.

The Panama Papers leaks last year revealed how Keith Schembri, the chief of staff to Malta’s prime minister Joseph Muscat, and then-energy minister Konrad Mizzi set up shell companies in Panama just monthsafter entering office in 2013. Schembri, is still in post, while Mizzi was removed from the energy ministry but remains a minister without portfolio.

The financial sector in Malta employs about 10,000 people and accounts for an annual 257 million euros in tax revenue from offshore companies held by foreigners. During the fact-finding mission of the European parliament’s PANA committee in February, a Maltese Labour Party MP told the panel that Malta’s use of low taxes to entice foreign wealth was a vital source of revenue for the archipelago’s economy, which has no natural resources or industry.

That appraisal meets with a consensus among the successive Christian democrat and social democrat governments. Meanwhile, most MPs also work in the finance sector or as lawyers, and have little incentive to change the situation.

EIC media partner Malta Today had to invoke Malta’s freedom of information laws to obtain information from the finance ministry in its report revealing how 2 billion euros were refunded every year to foreign-held companies. Apparently the substance of the official request was passed on in private to the finance sector lobby, for shortly afterwards by the bi-weekly newspaper was contacted by both a member of staff from PricewaterhouseCoopers and a former associate of Deloitte, two of the world’s four largest accounting firms; they asked Malta Today to refrain from publishing their findings, arguing that the report would undermine Malta’s efforts to contain the European Commission’s pressure on the Mediterranean island state to reform its fiscal policies.

But moves by the US, via the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), together with several large European countries, succeeded in convincing Malta to officially recognise the OECD’s definitions and regulations regarding money laundering and tax evasion, and this year Malta is to begin the automatic exchange of tax-related information on individuals and companies. It has also accepted to reduce the refund offered on company taxes by 2021. Meanwhile, like all EU member states, it is due to implement new EU tax directives by 2019.

But in practice, the path is a long one. In a summary of its meeting with the Maltese tax authorities, the PANA committee reported: “Malta only started last year with spontaneous exchange of information despite the fact that it is encouraged at EU level since 1977; they sent 3 messages and have not received anything so far. To a question on why they never sent spontaneously information, they raised the issue of lack of resources.”

Malta’s six-month term of presidency of the EU, which ends on June 30th, has unsurprisingly not been marked by advances in the fight against tax evasion; Malta (along with the UK, Cyprus, Luxembourg, the Netherlands and Ireland), has opposed the European Commission’s planned relaunch of the Common Consolidated Corporate Tax Base (CCCTB), which aims to make regulations governing the taxation of corporate profits uniform across the EU, and which would allow for taxing multinationals on the basis of their true activity in countries where they are present.

Such measures require the backing of all member states, and the informal alliance of European tax havens presents a common approach during meetings of EU finance ministers, with one or another using its veto against legislation to combat tax evasion.

Just recently, the Maltese rotating presidency of the EU was tasked with organising talks on defining the criteria by which tax havens - described as “non-cooperative tax jurisdictions” - outside the EU are identified on a blacklist, and against which a number of EU states are in favour of employing sanctions. Several of these have demanded that those states which apply no corporate taxes should be blacklisted, but the informal alliance of European tax havens has opposed the proposition on the basis that nations must be afforded fiscal sovereignty.

Malta was also during its current presidency behind the rejection of a European Commission suggestion that EU legislation on combating money laundering be amended to include a public register of the economic beneficiaries of trusts and “letter-box” companies.

-------------------------

- The French version of this article can be found here.

English version by Graham Tearse