There are several reasons why few people are keen to talk about the issue of the missing in Gaza, which neither the United Nations nor the local Palestinian authorities are able to put a figure to but which involves at least hundreds of cases.

One reason for the taboo is that the missing may include a significant number of members of the Izzedine al-Qassam Brigades, the military wing of the Palestinian Islamic militant group Hamas. Another is that it may also be explained by a growing clandestine exodus of Gaza inhabitants by sea, the perilous conditions of which have been horrifically demonstrated in recent tragedies.

Following the 50-day Israeli offensive against Gaza launched on July 8th, which Tel Aviv said was in response to rocket attacks on Israel by Hamas, 2,147 Palestinian dead – the large majority civilians – have been identified, along with some 11,000 wounded. But others remain missing, disappeared without trace.

Eid Abdelmonem Youssef Manoum has been seeking, in vain, news of his son Khaled since July 21st, one week after an Israeli bombardment destroyed their house situated in the city of Jabalia, the site of one of the largest refugee camps in Gaza.

Before the raid, Israeli military called Manoum at his home to tell him he must evacuate it, and several minutes later he took his family to his brother’s house, situated at the end of the same street. “Like us, Khaled did not understand,” said Manoum. “We weren’t hiding any arms, why bomb this house?”

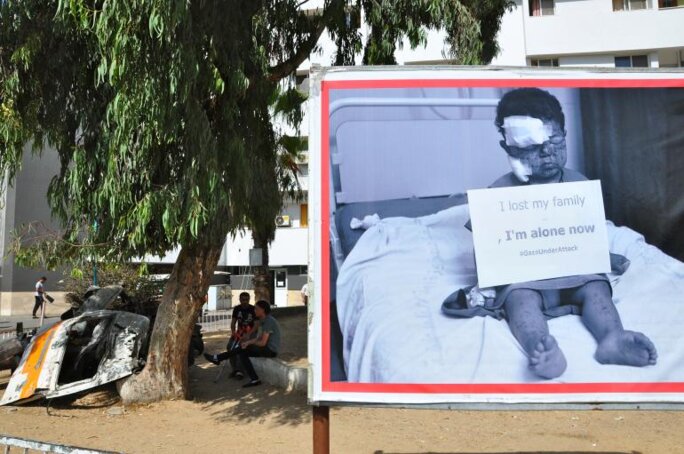

Enlargement : Illustration 1

Manoum has served as a police officer ever since Hamas took control of Gaza after winning parliamentary elections in 2006. But he says he is not a member of the movement. “They asked me to take up service in the police,” he said. “Before, I worked in Israel in construction work. With the blockade, it was no longer possible to travel everyday into Israel. But I’m not a militant, it’s just a job, and in the economic context that can’t be refused.”

On July 21st, the Hamas-run radio and satellite TV station Al-Aqsa announced that Manoum’s son Khaled had been killed along with ten other Hamas fighters during their incursion into Israel, close to a tunnel situated near the Erez Crossing on the Israeli-Gaza Strip border. “He was a painter, but I had proper doubts, for about some two years, that he was with the Al-Qassam Brigades,” said Manoum. “All the same I had no idea of the extent of his true involvement. Since the bombing of our house we didn’t see him much. He wanted to avenge himself, he told us."

Enlargement : Illustration 2

After the announcement that his son had died, Manoum contacted the Hamas and the Al-Qassam Brigades who told him that they did not know what exactly happened near the Erez Crossing, because they had lost radio contact with the group Khaled was with. He then did the rounds of hospitals, doctors and human rights’ organizations, but discovered nothing. Despite the then-ongoing war in Gaza, he decided to travel to the border to try and find out if someone knew of the incident, and to retrieve the body of his son. But this, too, was in vain.

“We called the Red Cross to get news,” said Manoum. “They told us they knew nothing, that they couldn’t tell us whether he was alive or dead. In the hospitals, some people told us they had seen him alive, others were absolutely sure he was dead. And then, the Israeli army broadcast a video, showing the annihilation of the battalion in which Khaled belonged.”

But Manoum and his family were unable to identify Khaled on the video (see above) and, unlike the families of the other fighters who died in the events, Manoum was never given back his son’s body. “All the others were able to bury their sons in dignity, us not,” he said. “And we can’t go looking at the spot, because we have no precise idea of the site of the tunnel where Khaled might have sought refuge when the Israeli army opened fire. Where is he? Did he die buried under the tunnel? Is he a prisoner in Israel? We have no further option, but sometimes I find myself hoping that he is still alive and a prisoner on the other side. My son was a fighter, he wanted to get away from this life and hurt the army which occupies us and bombs us, rather than do nothing and sniff glue like the youngsters here, who have so much hardship in finding enough work to be able to get married. He wanted to become someone. I’m proud of him.”

'He might be under rubble, or have left by sea for Europe'

Since the end of the conflict, hundreds of families have sought their missing relatives in hospitals and morgues. Their visits most often leave the officials and doctors feeling helpless in face of the problem. Iyad Zaqout is the administrative director of Shifa hospital, Gaza City’s largest - despite having just 583 beds. “During the war and since the end of the conflict we have had hundreds of people looking for someone close to them,” said Zaqout. “But most of the time we have no information to give them, because of the state of the bodies we have received which made people quite often difficult to recognise. Sometimes, there remained enough clothing for us to be able to show it to families. In those rare cases we managed to identify several people.”

Enlargement : Illustration 4

The number of people who have disappeared in this way appears nigh-on impossible to establish. The Gaza interior ministry has no information to offer on their numbers, just like the United Nations which has now ordered its staff on the ground not to comment on the issue. However, the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) commented in September that the phenomenon was a “major problem”.

“During the war, hundreds of families came to the office hoping we could help them to find a trace of their relatives,” said Masadi Seif, an ICRC official in Gaza. “Some victims are still under the rubble, and we don’t have the means of extracting them. Others were arrested during the land operation and are detained in Israel. By our position of neutrality, we have a good contact with the Israeli authorities, and we encourage all the Palestinian families who want information to come forward to us.”

“But I can’t tell you how many detained people there are, we are not authorized to reveal that information,” he added. “At the same time, our teams on the ground continue to collect the maximum amount of information about the disappeared of Gaza.”

Enlargement : Illustration 5

Fadi Abu Shammala is a member of the Marxist-Leninist Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine (PFLP) and a project director with the General Union of Cultural Centers, a Gaza-based NGO dedicated to supporting Palestinian cultural identity. “Several families in my neighbourhood are in this situation,” he said. “Myself, I am without any news of my cousin since the end of the war. As far as I know, he might be under the rubble, or have left by sea for Europe.”

That is the final hypothesis of what mat have become of a number of those missing, and one which greatly concerns the Gaza authorities. On September 10th, a boat carrying more than 400 migrants - and possibly as many as 500 - west along the Mediterranean Sea to Europe sank in international waters south-east of Malta. Survivor accounts say half of them were Palestinians, originally from Gaza and Egypt, from where the ill-fated journey began.

Other passengers included Syrians, Egyptians and Sudanese nationals. There were just 11 survivors, including eight Palestinians.

According to a report on the tragedy by the Euro-Mid Observer for Human Rights, a Geneva-based NGO dedicated to upholding human rights in the Middle East and North Africa, the people traffickers who organised the journey –and who, it details, were responsible for the disaster – scouted for some of their clients directly in Gaza. “Travel agencies in different locations - including offices in Egypt and ‘intermediaries’ in Gaza - recruited the passengers,” said the NGO, whose information was in part based on interviews with survivors and their families. “Travellers were promised a safe journey to Europe on a secure and comfortable ship. Recruits in Gaza paid US$2,000 - $4,000 per person, reportedly based on assurances from persons who claimed to have previously used the smugglers’ services.”

Rami Abdu is the director of Euro-Mid Observer’s office in Gaza, established in November 2011. “This phenomenon, which consists of wanting to reach Europe by high-risk routes and means, coincides in Gaza with the beginning of the last war,” Abdu said. “We are in direct contact with the Gaza authorities, who have not yet detected in Gaza a specialized ‘mafia’ in this business like that present in Egypt since decades. It is more about isolated smugglers who try to profit from the situation and the war, and who make Gaza inhabitants pay between 2,000 and 4,000 dollars per person to get into Egypt and aboard the boat.”

Following the September tragedy, the NGO interviewed the eight Palestinian survivors. The boat they were all travelling on, whose water pump had stopped working, was, according to the survivor accounts, deliberately rammed by the smugglers after the migrants refused to climb, mid-sea, aboard a smaller vessel they believed was unsafe.

Most of the passengers drowned immediately, while survivors estimated that between 100 and 150 of the passengers were left clinging to debris. All but 11 of them subsequently died over the following four days before a passing cargo ship began the rescue operation.

One of the eight Palestinian survivors, Shukri al-Assouli, from Gaza, told Euro-Mid Observer of the horror of the four days adrift on the sea. He lost his wife, four-year-old daughter and nine-month-old daughter in the tragedy. “I was with about 50 survivors, and we stayed with each other hoping that rescue teams would come,” he said. “Night and day passed while we were in the sea. At night the water was very cold and during the day the sun burned our skins. Our numbers were decreasing, and a friend of mine held onto a corpse because he didn’t know how to swim.”

Al-Assouli, 33, and two other survivors from Gaza, 25-year-old Abdel Majeed al-Hila and 23 year-old Mohammed Radeh, were also interviewed earlier this month by British broadcaster ITV News in Athens, where they are temporarily housed by Palestinian diplomatic mission staff. Al-Hila, a student, told ITV that he left Gaza after his home was destroyed, when he had "nothing left to make me stay", adding: “I would dream of sleeping one night without hearing bombing or shelling - just wish I didn't see death for one day.”

Radeh said he had heard about the dangers of the clandestine crossings to Europe by sea. “But with the pain and circumstances I was living in - if my destiny is death, dying quickly was a better option than dying slowly in Gaza,” he said.

Euro-Mid Observer said that after the September tragedy, and except for a Maltese navy search of the island’s coastline which found two corpses, there was no coordinated international search with the Italian and Greek navies to find the bodies of the hundreds missing.

-------------------------

- The French version of this article can be found here.

English version by Graham Tearse