Gérard Crozier, the mayor of Allex, a hilltop village in the Drôme Valley in south-east France, spoke clearly and with a firm tone of voice as he addressed a municipal council meeting in the village hall on September 13th over his proposition for holding a referendum.

“This decision, I take it entirely upon myself,” said Crozier, who leads a council majority made up of a right-wing alliance. “I’m under nobody’s thumb. There is no intention of calling into question France’s tradition of welcoming [outsiders], but rather to give citizens the possibility of expressing themselves with regard to the directives that the state wants to impose upon us. These past few days, lots of people have come to see me to say ‘we elected you so that you’d defend us’. That’s why I want to organize a consultation process.”

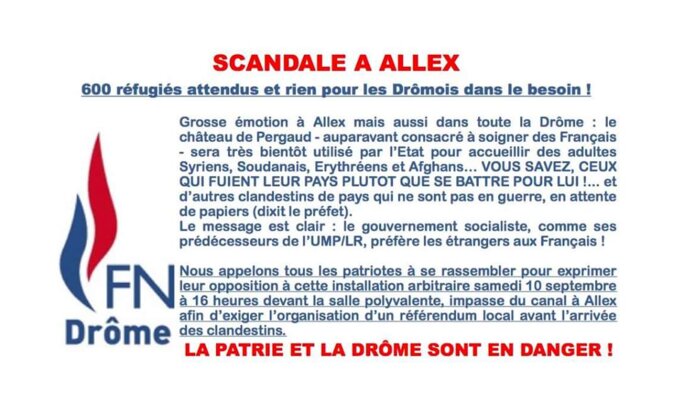

Enlargement : Illustration 1

During the meeting there was lengthy murmuring among the attendance of about 100 people, and when the final vote was counted a good half of them erupted into loud applause. The motion for a referendum was passed and the village’s 2,500 inhabitants are now due to vote on October 2nd in response to the following question: “Are you for or against the reception of refugees in the commune?”

But the referendum has little chance of cooling the tensions prompted by the announcement that the nearby Château de Pergaud, situated three kilometres from the village hall, is to house a reception and orientation centre (Centre d’Accueil et d’Orientation), or CAO, for migrants. Managed by the Protestant diaconate, the CAO is due to open in a matter of weeks, when it will receive about 50 migrants. The length of a migrant’s stay will vary between one and three months, the time for them to turn themselves around and submit asylum requests. After that, they will be sent off to one of the various reception centres for asylum seekers, called CADAs, around France.

“I spoke with the mayor about this project as of last July 21st,” said Éric Spitz, prefect of the local Drôme département (equivalent to a county). “We visited all the buildings together. At the information meeting on September 5th I answered legitimate questions put by the inhabitants of Allex. The discussion was held in a calm atmosphere, which is why today I find it a little difficult to understand the reactions of some.”

Walking the streets of Allex, it was not hard to find people opposed to the project. “I don’t say that they are all criminals, but I live alone and to see all these men arrive makes me frightened,” said Francine, fifty-something, who struggles to get by with some house-cleaning work. “I no longer have any right to universal healthcare, and we give money to migrants. Do you find that normal?”

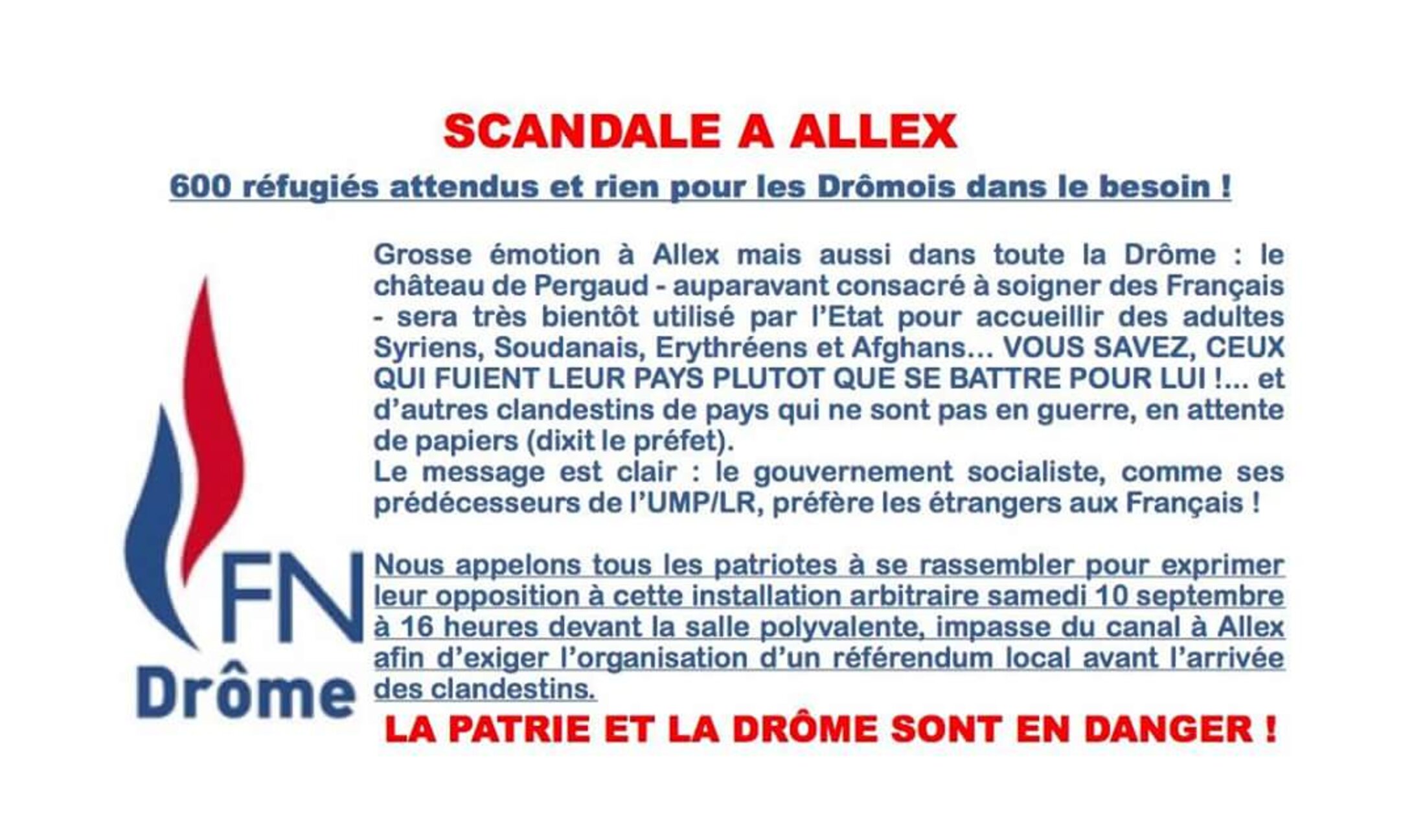

Enlargement : Illustration 2

In the café-tabac on the main square, Françoise sits behind the till. “What people find regrettable is that the setting up of the centre was very rapidly imposed upon them,” she said, echoing the sentiments of a vast majority of villagers. Another inhabitant complained: “Before, alcoholics were treated at the Château de Pergaud, but through lack of financial means the structure closed several years ago. On the other hand, for foreigners, there’s no problem for the cash to arrive.”

According to an interior ministry document cited by French daily Le Figaro on September 13th, the government plans to create “between now and the end of 2016” places for more than 12,000 migrants in CAOs in order to reduce numbers living in the makeshift ‘jungle’ camp of in the Channel port of Calais, and also in the makeshift camps of migrants in northern Paris. To meet this goal, an extra 8,000 beds must be found on top of the 5,000 that will be available at the end of September.

“The CAOs are an airlock that allow for giving people shelter,” said Jonathan Sorel, an advisor to housing minister Emmanuelle Cosse. “Their implantation across the country is aimed at widening out the reception policies. National solidarity must come into play, and in the majority of cases everything happens smoothly.”

However, on September 7th in Forges-les-Bains, a village situated a short distance south of Paris, a CAO which was due to open imminently was badly damaged in an arson attack. Local opposition to the centre prompted the authorities to lower the initially planned capacity of 100 migrants, and to provide for gendarmerie patrols to be present for start and ending of classes at the nearby infants and primary school situated close to the centre.

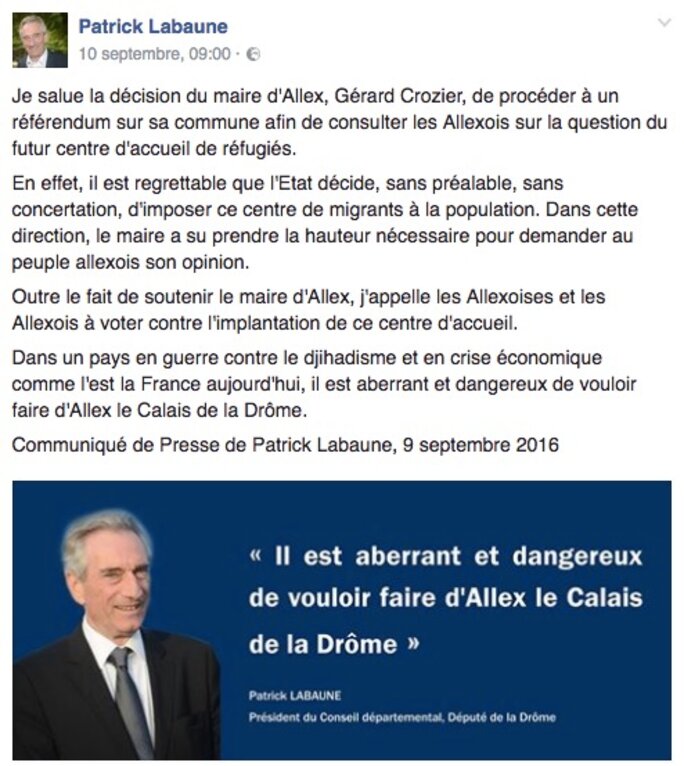

Enlargement : Illustration 3

Back in the Drôme, Jean-Jacques Bosc, the director of the protestant diaconate that will manage the CAO at the Château de Pergaud, said everything was ready for the shelter to open. “We’re ready to receive the first migrants, we’re just waiting for the green light from the prefect,” he said. The diaconate also manages a centre for asylum seekers in the town of Valence, about 20 kilometres north of Allex. The Château de Pergaud is the property of the Social Hygiene Committee of the Drôme, and latterly was the site of a rehabilitation centre for alcoholics and drug addicts until the structure closed in 2015. “We took over the management of the reinsertion centre at a time when it had serious financial difficulties, and until July 2018 we enjoy an extremely low rent of 400 euros per year,” explained Bosc. “We have teams that are trained and ready to intervene. I am sure that, when the first refugees will arrive, the pressure will drop of itself. The problem is that certain political parties don’t hesitate to exploit the fears.”

'In the villages of the region, people are becoming agitated'

With presidential and parliamentary elections due in the spring of 2017, the arrival of migrants in Allex gave the far-right Front National party an opportunity to increase support for it in the region. Already, in regional elections held last December, it garnered 26.78% of votes cast in Allex. “When we learnt that the Front National intended to demonstrate on Saturday September 10th, we urgently mobilised our networks so as not to hand the village square to the far-right,” said Yvon (last name withheld), a member of the Association for Solidarity with Immigrants, based in the small town of Crest, a short distance from Allex.

A woman resident of Allex described the events that Saturday in the village. “The Front National members, who came from across the region, marched through the streets shouting ‘This is our home’,” she recalled. “There was something terrifying about it. We waited for them in front of the village hall to stop them taking over the building. They numbered 150, we were about 200, and we had the misfortune to recognise in front of us some of our neighbours. In a small village like ours, you must imagine the symbolic violence that that represents.”

Enlargement : Illustration 4

On flyers handed out in the streets the day before, the National Front called for the organization of a referendum to prevent the arrival of what it called “those who flee their country rather than fight for it”. No-one Mediapart talked to could remember the Front National mounting an operation as large as that in the region. “The government is hiding migrants in far-flung countrysides, this invasion must be stopped,” said Frédéric Marcel, a Front National official and party secretary for a constituency in the Drôme, who was present at the September 13th meeting of the Allex municipal council when the referendum was decided. “We are the only party to help the population of Allex defend itself and we are happy that our demand for the organization of a consultation was acted upon,” said Marcel.

For his part, the mayor of Allex, Gérard Crozier, denies having acted under pressure from the Front National. He said the idea for the referendum came from one of his municipal councillors, in reaction to demands by local inhabitants, and it was presented in order to cool “an explosive situation”.

However, the referendum is considered by the prefect of the Drôme to be “illegal”. He issued a statement underlining that the decision to set up a refugee shelter at the Château de Pergaud is the responsibility of the state, and not the local authorities. “We are going to exhaust ourselves in organizing this needless referendum whereas we could have had the time to go out and meet with inhabitants, to put in place a true policy of solidarity, and to take the advice of municipalities which already have these types of centres,” said Monique Manchon, an opposition councillor.

“We sacrifice our traditional values of receiving people for electoral manoeuvring which is beyond us, and this manipulation dangerously exacerbates feelings,” commented Christophe Burling, another opposition councillor.

Patrick Labaune, a local Member of Parliament (MP) for the conservative Les Républicains party, who is also head of the Drôme département council, took to Twitter to “salute” the referendum decision by the mayor of Allex and caling on the villagers to vote against the opening of the centre. “In a country at war with jihadists and in an economic crisis, as France is today, it is absurd and dangerous to want to turn Allex into a Calais of the Drôme,” wrote Labaune. His message was swiftly followed by similar messages of support for Gérard Crozier (as reported by regional daily Le Dauphiné) from mayors of surrounding villages and towns, including the Républicains party MP and mayor of Crest, Hervé Mariton. “In the villages around the region, the population is becoming agitated, with the inhabitants asking their elected representatives ‘what would you do for me in this situation?’,” commented Marlène Honorat, journalist with the local weekly, Le Crestois.

“The mayor of Allex didn’t call me up before proposing the organisation of this consultation, he’s big enough to take decisions himself,” said Républicains party MP Patrick Labaune, speaking to Mediapart by phone. Gérard Crozier’s daughter Céline was until last year Labaune’s parliamentary assistant, and she now holds the post of chief-of-staff on the Drôme département council, which is presided by Labaune. “The history of Allex is the same as numerous villages in France,” added Labaune. “It’s time to put a stop to immigration and to deal with the networks of human traffickers.” He however had no solution to offer for the dismantling of the dire ‘jungle’ camp in Calais, which members of his own political party in the Channel coast region of north-east France have been demanding for months. But Labaune has now launched an online petition against the refugee shelter in Allex.

Associations in the Drôme Valley dedicated to helping migrants are keeping a low profile while waiting for the first of them to arrive. “During the war in Bosnia-Herzegovina, at the beginning of the 1990s, villages in the region had received lots of refugees, and this tradition is reactivated with this new migratory wave,” said Colette (last name withheld), a retired psychologist who is a member of one of the associations, the Val de Drôme Accueil Réfugiés. Created in 2015, the association, which counts about 200 voluntary workers, has been active in helping with the social insertion of several Iraqi families who have been granted asylum in France and who are being lodged by volunteers around the town of Crest. “When people meet up, mistrust disappears and the exchanges are beneficial for everyone,” added Colette.

-------------------------

- The French version of this article can be found here.

English version by Graham Tearse