The introduction to this article was updated 31/1/2011: The future of Egyptian President Hosni Mubarak's regime remains uncertain amid a movement of popular protest unprecedented in all his 31-year rule.

Just as in Tunisia, the explosion of unrest that reached the streets on 25 January is a climax of years of simmering revolt against corruption, unemployment and rising prices. It has also similarly illustrated in a dramatic manner the key role of the internet and social networks in bypassing the censorship of an authoritarian regime. Websites, blogs, Facebook, YouTube and Twitter have become essential tools for dissidents to communicate and spread revolt, as highlighted in a US diplomatic cable revealed this week via the Wikileaks disclosures.

On 28 January, Mubarak, 82, ordered the interruption to internet connections across the country and a suspension of mobile and landline phone services in certain areas. That followed interference earlier during the week with connections to Twitter and Facebook.

Egypt has an estimated 17 million internet users. The Facebook page of Mubarak's principle opponent, Mohamed ElBaradei, Nobel Peace Prize winner and former head of the International Atomic Energy Agency, reportedly placed under house arrest Friday, counts more than 240,000 ‘friends' (see it here).

In a country subjected to more than 30 years of State of Emergency laws that have effectively muzzled the traditional media, the internet has become, notably over the past five years, a unique refuge for democratic discussion and debate. "Violence will not address the grievances of the Egyptian people, and suppressing ideas never succeeds in making them go away," US President Barack Obama said on Friday.

Mediapart editor François Bonnet travelled to Egypt last year to meet with some of the country's most prominent cyberspace human rights activiists. Presented here in the following five portraits, they provide a chilling insight into the events that were to erupt this month.

-------------------------

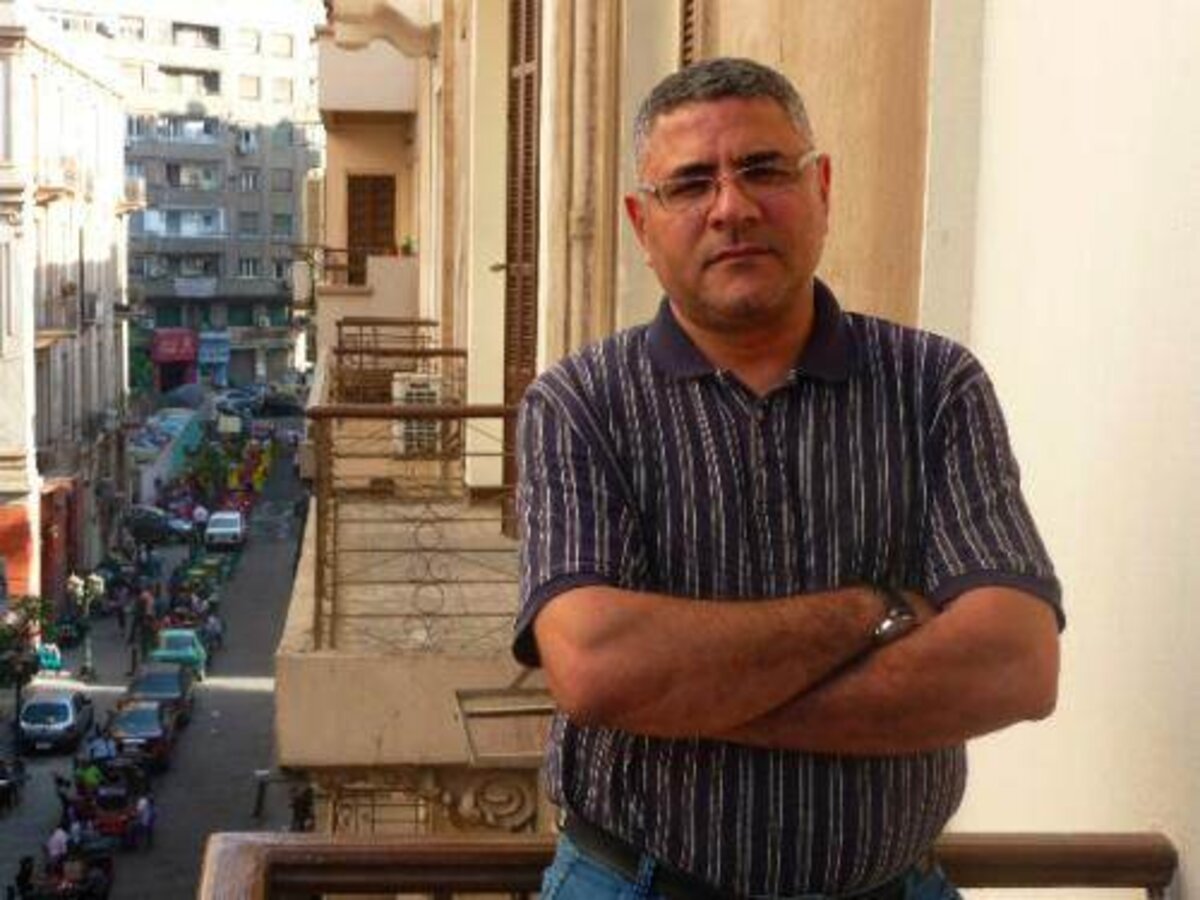

1. Gamal Eid: 'A judge tried to ban 49 sites in one go'

A former lawyer involved in several high-profile human rights cases in Egypt, Gamal Eid is now the executive director of the Arabic Network for Human Rights Information, ANHRI, which he founded in 2004 (click here for its website in English). ANHRI is the largest association for the defence of freedom of information in the Arabic world, built as a network for the surveillance of the abuse of fundamental freedoms. His outward good humour hides with difficulty his inner deep concerns. He says that every morning, after he arrives at work in central Cairo, he can never be certain of returning home at night.

"The government is a lot more dangerous today than it was in 2004 and 2005, because the situation is very unstable," he says. "It is something new for the authorities. People are less afraid, there have never been as many demonstrations, the country is in fervor. Everyone feels very well that it is the end of a certain world, no-one wants Mubarak's son, new networks are being created. The 2011 elections will be the most important since those of the 1960s."

A veteran legal combatant in cases launched against the press, Eid is today one of several lawyers defending numerous bloggers who have been targeted by the Mubarak regime.

"Journalists can be arrested, prosecuted, but are rarely imprisoned," he explains. "This is not the case for bloggers who have less protection under law. In May, three of them were imprisoned. One was sentenced to three years in prison and a heavy fine for having written a poem of six verses that was judged to be insulting towards President Mubarak. In another case, a judge attempted to ban 49 internet sites in one go."

The country's legislation and its interpretation are akin to moving goal posts. The State of Emergency, in vigour since 1967 save a brief interruption between 1980 and 1981, was modified last year, when it became less restrictive towards the press. But it still allows the authorities wide room for manouevre.

"It is not the law that governs, it is the political decisions," Eid says. "But it also partly depends on the judge, what's happening at any one time, and political tensions. That's what Mohamed ElBaradei tested when he launched into politics. While the four major opposition parties are divided over their support for him, activists and many journalists support him and that has caused numerous problems. Because he mobilizes via the [social] networks, which the authorities did not foresee."

While the authorities can attack digital publications, it is a lot more difficult to control social networks, and in particular Facebook, the most popular in Egypt.

"I think Youtube, Facebook, Twitter and Flickr change a lot of things, because the information that passes through them cannot be stopped," Eid says. "Look at Iran, it was the Iranian demonstrations that launched the trend for Twitter in all the countries of the region."

2. Mahmoud Abdel Monem: 'Security call me every day, I should be worried'He has the face of a teenager and speaks slowly and attentively. Mahmoud Abdel Monem, 30, has become one of Egypt's best-known bloggers, which opened him up a career as a journalist three years ago. He is also one of the best-informed specialists on the Muslim Brotherhood.

He worked on the opposition daily newspaper al-Dustour until last autumn, after it was bought by Elseyed el-Badawi, a business tycoon and leader of al-Wafd, one of the parties among the divided opposition. The paper's editor Ibrahim Eissa was sacked within months of the takeover and a number of the editorial staff then quit the paper.

A former militant member of the Muslim Brotherhood, from which he has now distanced himself, Mahmoud Abdel Monem was imprisoned in 2003 when, he says, he was "tortured and beaten for three days." He first created a blog in 2006 to recount the events that followed another imprisonment, earlier that same year, along with 1, 500 other members of the Muslim Brotherhood and some 50 members of Kefaya, the Egyptian Movement for Democratic Change.

"In 2006 I was imprisoned without trial for six months," he recounts. "The internal security [services] simply considered me to be a political prisoner, and I was interned at the Tora prison, which was in fact more or less alright [for conditions]. In 2007 I was invited to Sudan. They arrested me at the airport and I was held for two months in El Melkhem prison, where it was very tough. I have been banned from leaving the country since 2008. I was unable to go to Morocco or the United States. I am waiting for a decision from the chief prosecutor and internal security call me regularly. I should be worried."

Monem's blog about his experiences in jail in 2006 met with quick success. "It was a good opinion poll," he recalls. "There were the sympathetic, the doctrinaire, the unpleasant. I wanted to show the diversity of paths, of projects. I wanted to explain that there were also normal people. That this movement was not closed, dogmatic. The blog allowed me to do something that was more personal. Today, it is of course more political. I analyse the evolution of Islamic movements."

He makes no secret of having now moved away from the Muslim Brotherhood, and speaks of his fascination for the political process in Turkey, and the manner in which Turkish Prime Minister Recep Tayyip Erdogan's ruling conservative Muslim party, the AKP (Justice and Development Party), exercises power. "But I continue to think that the Muslim Brotherhood are a rampart against extremists and al-Quaeda," he says. "They accompany the evolution of Egyptian society which is heading, in terms of values, towards conservatism to try and escape the authoritarianism of this regime. It is this regime that uses your aid [money] for the development of the Salafists.1"

"I define myself as a moderate and reformist Muslim. That is why I view the Turkish AKP with a great deal of admiration. Mordernisers no longer carry any weight at the heart of the Muslim Brotherhood. The movement has become withdrawn, and is less involved with a political strategy. It is one of the great forces of this country but won't enter into direct confrontation with the Mubarak government."

-------------------------

1: The Salafists are among the extremist Islamic groups present in Gaza and which share an ideology in common with al-Quaeda.

3. Esraa Abdel Fatah Ahmed: 'Society is suffocating'

Enlargement : Illustration 3

She is behind internet site Elma7Rosa.net. Its core activity is an internet radio station, although it also carries blogs. Above all, there is also Facebook and Twitter.

Esraa Abdel Fatah is in her 20s and is one of those young activists that have become a nightmare for the Egyptian regime. She describes herself as a ‘media coordinator'. A virtuoso of digital tools, she is above all a civil rights militant involved with several associations.

The principle one among these is the Egyptian Democratic Academy, affiliated to the Egyptian Democratic Institute. Both are non-governmental organizations (NGOs) financed by the German Friedrich Nauman Foundation for Freedom1. The Egyptian NGOs train young people in media production (radio, video and blogs), and in basic organization administration, legal procedures and election monitoring.

Esraa taps into her Blackberry while following Facebook on another screen. "Facebook, Twitter, people live on that," she says. "Everybody's there, why create an isolated website? Young people don't buy newspapers, everything is on social networks, it's the only way to get news out fast."

Esraa was one of the instigators of the so-called ‘April 6th Movement'. "Originally, it was Facebook group that called for a strike in March 2008 in protest at the rise in food prices," she explains. "We were arrested on April 6th. I did 18 days in prison then I was freed on the orders of the chief public prosecutor. But the group still exists and today it has 70,000 subscribers. They are mostly young people, many of whom are students."

Thanks to webtools, she is able to bypass the political parties she considers to be arthritic and controlled activism. "This regime is solid," she says. "People are afraid of the repression that has become stronger these past few years. The authorities accuse us of being henchmen for foreigners, they want to dirty us and [they] dismiss the internet in all kinds of manner. But I think our society is suffocating, that people are little by little realizing this. So the situation is quite unpredictable, and I think the engagement of [Mohamed] ElBaradei in Egyptian politics has sparked many things."

On 15 January, Esraa Abdel Fatah and two well-known bloggers, Wael Abbas (see his portrait on next page) and Shahinaz Abdel Salam, were among 20 human rights activists arrested when they tried to enter the southern town of Naga Hamady. They had travelled there to testify their solidarity with the families of six Coptic Christians shot dead outside a church in the town, along with a policeman, one week earlier. The police put them on a train back to Cairo.

--------------------

1: Set up in 1958 by the then-West Germany's first post-war president Theodor Heuss, it describes its mission as dedicated to promoting the cause of democracy and civic education wordwide.

4. Wael Abbas: 'Everyone knows, even at the top, that it cannot continue'

Enlargement : Illustration 4

Wael Abbas is undoubtedly one of Egypt's most radically engaged anti-regime blogger, and one of the best-known. Aged 36, he has spent the last 15 years as an activist. He made his name after publishing on the internet, in 2005, photos and video of security forces brutally beating demonstrators and regular torture carried out in police stations (to see his blog, click here).

"I published terrible pictures of torture, victims' wounds," recalls Abbas. "More than twenty-five videos. The impact was enormous. It was the first time that there had been such an implication of the authorities and it was just after the revelations of the torture carried out by the Americans in the Iraqi prison of Abu Ghraib. Imagine the effect, people immediately connected the two."

He believes Egypt's bloggers were responsible for waking up the country's newspapers which had lost their edge, some fearful of attacks from censors and national security agencies. "Blogs pushed back the limits of our freedom," he comments. "The opposition newspapers, previously very hesitant, were forced to follow a bit."

Abbas previously worked as a journalist for foreign news agencies, but today is blacklisted. His situation is considered too dangerous for foreigners to work with him. "I have been arrested several times and each time held for several hours," he explains. "I was twice sentenced to six months in prison, then later acquitted. Three bloggers are in prison now, one for the past four years."

Abbas says he tries "to cover events that other media don't cover, demonstrations against Gamal Mubarak1, clashes between Muslims and Christians". He also writes analyses and encourages debate: "People discuss on my blog. I want to provoke people into an awareness. These blogs obviously won't be sufficient to change society but they allow you to inform, to debate, to reveal and they force other media to react. Civil society in Egypt must be stronger. We must replace the mosque and the government."

Abbas is afforded relative protection by his celebrity, and is regularly invited to conferences abroad. "Mubarak has frozen the democratic process for thirty years," he says. "More and more people, even at the top, understand that it can no longer continue like that."

5. Ibrahim Mansour: 'We must grab our liberty every day'

Enlargement : Illustration 5

Last autumn, Ibrahim Mansour was on the receiving end of what Wael Abbas says "can no longer continue". Until October, he was executive editor of the opposition newspaper al-Dustour, an incisive and influential daily which he had championed for five years. It was bought last summer by Elseyed el-Badawi, a business tycoon and leader of al-Wafd, ostensibly an opposition party but one which is careful not to cut off its relationship with the Mubarak regime. One month before last year's parliamentary elections, el-Badawi sacked both Mansour and the paper's executive editor-in-chief, Ibrahim Eissa, one of Egypt's best-known journalists.

In 2008, Eissa was sentenced to two months in prison for publishing an article about the ill-health of President Hosni Mubarak, who later pardoned him. But the sacking of the two men last year came just as the paper was about to publish an article by the opposition figure Mohamed ElBaradei.

Ibrahim Mansour was supported by a group of editorial staff who have since joined him on the internet for the launch a major news website (available here). "I have always worked as if it was the first and last day," says Mansour. "Al-Dustour was a liberal newspaper that denounced repression and corruption and which wanted to prepare an alternative to the regime. We will continue."

"For thirty years we have lived with this State of Emergency law. Our liberty is based only in the courage of people, we must grab it every day. Yes, we supported ElBaradei because we think that he can intelligently bring a force for change and that the process runs the risk of being a long one. Because there is in this country a situation of chaos, with a totally opaque regime where even the group that governs with Mubarak doesn't know what will happen next. And, meanwhile, it is the security forces that govern here, whereas Egypt deserves a truly democratic government."

In a country where newspapers are watched over by the security services and heavily dependent upon major advertisers linked to the authorities, blogs played a key role, says Mansour. "Newspapers supported them and I believe in the strong impact of this new system," he adds. He concluded that however long the process might be "political change now seems to me inevitable."

-------------------------

1: Gamal Mubarak, 47, is the younger of Hosni Mubarak's three sons, and seen by many as the groomed, intended successor to his father.