It is impossible to miss the giant poster in front of the Arab World Institute (AWI) on the banks of the River Seine in Paris. It reads: “Al-Ula: Merveille d'Arabie” ('Al Ula: Marvel of Arabia'), the title of an exhibition at the institute. The word 'Saudi' does not accompany Arabia in the title; some speculate this was done so as not to put off the Parisian public.

This exhibition plunges us straight into the heart of a kingdom which is ruled with a rod of iron by the Saudi Crown Prince Mohammad bin Salman or MBS as he is often known. But the casual visitor will discover nothing here about the abuses committed against political opponents or about the war in Yemen.

Instead the exhibition, which runs till March 8th, is devoted to the natural and archaeological site of Al Ula in the north-west of the country, an ancient city and region which lay at the crossroads of the incense routes that once crossed Arabia. The accompanying words read more like tourism brochures than scientific or historical texts. They talk of a “fabulous saga” in a valley where “life is pleasant and prosperous”. Visitors are treated to panoramic photos by the photographer and environmental activist Yann Arthus-Bertrand, while there are also archaeological remains. At the end of the tour a video declares, rather like an advertising slogan: “Al Ula, everyone who visits it wants to return there.”

Enlargement : Illustration 1

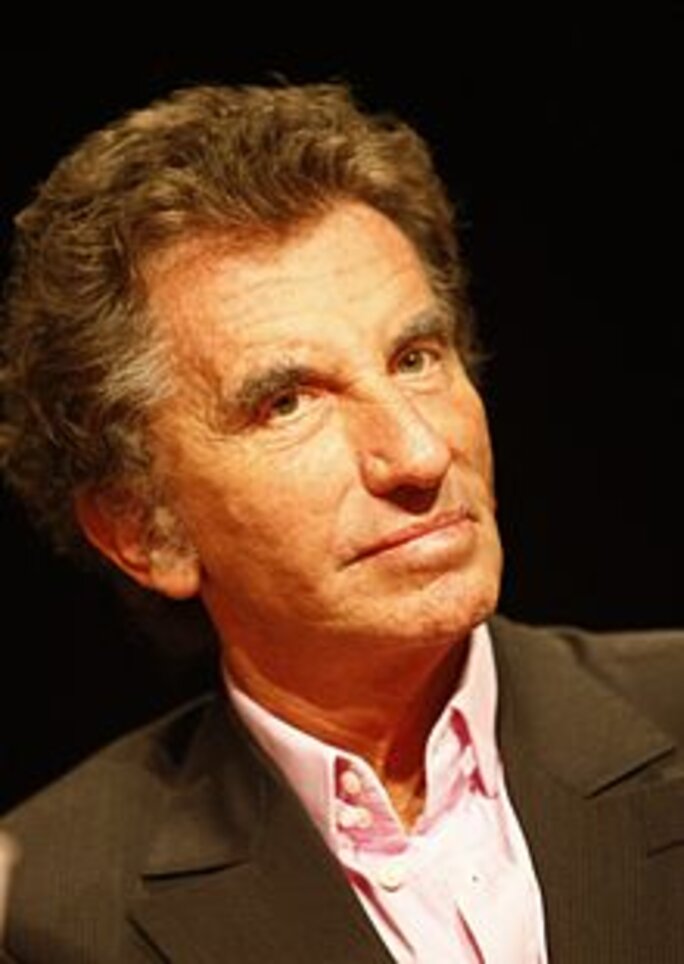

The former culture minister Jack Lang, who is now president of the AWI, told Mediapart: “The exhibition was wholly funded by Saudi Arabia.” He added: “Our grant from the Ministry of Foreign Affairs allows us to pay for the running of the building but we need sponsors for the exhibitions.”

And not only for the exhibitions: Saudi Arabia has already spent 5 million euros on the AWI building, which was designed by celebrated French architect Jean Nouvel. Meanwhile Jack Lang's right-hand man, the director general of the AWI, is Saudi national Mojeb al-Zahrani, and the institute's diplomatic advisor is Éric Giraud-Telme who was previously chef de mission at the French embassy in Riyadh. There is, it seems, a close relationship between the French Ministry of Foreign Affairs and the Saudi kingdom. “There are indisputable sign of the regime opening up,” insisted Jack Lang. “Saudi Arabia is nothing like Iran.”

This exhibition at the AWI, which is just a 45-minute walk from the Foreign Ministry on the banks of the River Seine, is just the visible part of Franco-Saudi relations. Since Emmanuel Macron came to power the two countries have begun a massive cultural partnership. “Saudi Arabia is turning the French cultural elites into clients,” Stéphane Lacroix, a researcher at the Centre for International Research (CERI) at Sciences Po university in Paris, told Mediapart. “This is all about a strategy of influence: having forged political and economic links with the United States, Saudi Arabia has got close to France through culture, hoping Paris will form a bridge with Europe.” He added: “It's classic Saudi Arabian politics: to use contracts to obtain political support, both with weapons and with culture.”

The regime is using this approach to earn international respectability, while also diversifying its business activities in a bid to move away from being a rentier state, dependent on the commercialisation of its natural resources. “There's a clear paradox; on the one side MBS portrays himself as a reformer to Westerners, and on the other side he is stepping up repression more than ever,” said Amnesty International's Katia Roux, a specialist in the region. “The outcome in terms of human rights is catastrophic. The regime tortures opponents, criminalises homosexuality and discriminates against women.”

The Franco-Saudi cultural partnership was born in November 2017. After he had inaugurated the Abu Dhabi Louvre museum in the United Arab Emirates, President Emmanuel Macron decided at the last minute to extend his visit in the Arabian peninsula by stopping off at Riyadh where, at the airport, he had a three-hour meeting with Mohammad bin Salman. The pair discussed Iran and the war in Yemen. But what the official communiqués did not say is that during the meeting MBS offered France a massive cultural partnership.

“MBS is a fervent admirer of Abu Dhabi’s crown prince Mohammed bin Zayad Al Nahyan and wants to take inspiration from his cultural policy,” said Stéphane Lacroix. Saudi Arabia is also trying to make up ground in this regard in relation to its neighbour and enemy Qatar. But MBS did not just want yet another museum: he proposed that France develop the entire site of Al Ula which is an area the size of Belgium. This project involves the building of around ten museums, auditoriums and hotels, and its cost has been estimated as somewhere between 50 billion and 100 billion euros. The Abu Dhabi Louvre was simply a dress rehearsal.

When he got back to Paris, Emmanuel Macron handed responsibility for the Al Ula project not to a person from the world of culture but to a man called Gérard Mestrallet, who was then chairman of the board of directors at the French energy and utility giant ENGIE, where he had been managing director for eight years. The reason was simple: ENGIE is the second largest French investor in Saudi Arabia after the oil company Total and Gérard Mestrallet was – and still is – a board member at the Saudi Electricity Company. The message was clear: culture must help France's economic interests.

The agreement was ready for MBS's arrival in Paris in April 2018. His French hosts put on a charm offensive: a dinner held at the Musée des Arts Décoratifs ('Decorative Arts Museum') in the French capital was attended by France's cultural elite. The guest list included the then culture minster Françoise Nyssen and Jean Nouvel. During his Paris trip MBS was accompanied by a man called Maher Abdulaziz Mutreb. Six months later this close aide to the crown prince was present at his country's consulate in Istanbul where he is suspected of being the head of the Saudi unit that went to murder the dissident journalist Jamal Khashoggi.

MBS's visit to Paris ended with the signing of an intergovernmental agreement on the development of Al Ula, and the setting up of a dedicated agency to oversee this. The management of this was, not surprisingly, handed to Gérard Mestrallet. The latter also sits on the Al Ula consultative committee set up in Saudi Arabia alongside Jack Lang and Irina Bokova, the Bulgarian former director general of UNESCO – the body which has recognised Al Ula as a World Heritage site.

'It costs France nothing and it brings in money'

This was not the only cultural agreement that has been signed; three other accords have been ratified between France and Saudi Arabia. These involve the creation of an orchestra and opera at the Opéra de Paris; the training of young Saudi professionals at the film and television school Fémis; and, with the National Audiovisual Institute (INA), a project to digitise the country's archives.

Two years later and the Al Ula development agency, known as Afalula, has been set up in sumptuous offices in Rue de Courcelles in central Paris. It is a simplified joint-stock company with the French state as its only shareholder but all the running costs are paid for by Saudi Arabia. Mediapart understands that these costs are around 30 million euros a year. “This organisation is an asset: it brings together all French interests,” said a source close to Gérard Mestrallet. The source added: “It costs France nothing and it brings in money.”

Behind the cultural front, those involved in promoting France's economic interests are hard at work. This is not surprising given that the sums involved are greater than for arms sales, which themselves represented 12 billion euros between 2007 and 2016. And the effort is already paying off: the hotels on the new site in Saudi Arabia have already been awarded to France's hotel and resorts chain Accor.

The first member of the French government to visit Saudi Arabia after the Jamal Khashoggi scandal was in fact the culture minister Franck Riester, who went there in February 2019. That was deemed less risky from a media coverage point of view than a visit by the defence or foreign minister. Indeed, the Ministry of Culture has created its own teams internally to help in the process of cultural diplomacy.

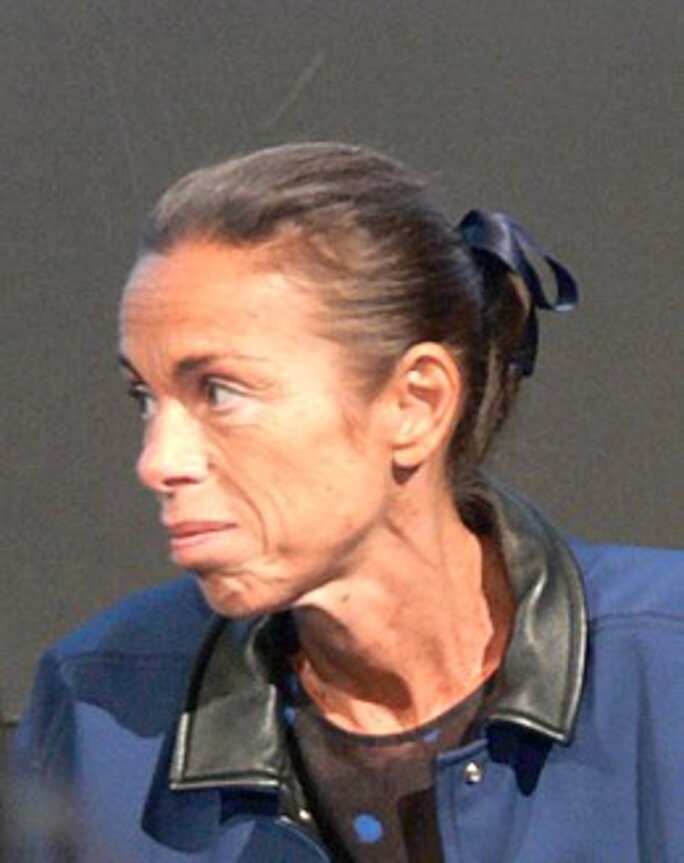

The case of Agnès Saal is instructive here. After being convicted in 2016 over her excessive taxi bills while president of the INA, she joined the Ministry of Culture in 2018 as a senior civil servant overseeing equality and diversity. Her appointment caused controversy but her mission is a useful one: to fight against discrimination in cultural institutions. But what is less well known is that Agnès Saal is also head of the international cultural expertise mission at the ministry. Mediapart understands that it was in this capacity that she hosted a delegation from Jeddah on the 4th and 5th of July 2019. It is a curious and unhappy paradox to defend the place of women in culture in France while at the same time pulling out all the stops for a regime which discriminates against women.

The cornerstones of the partnership between France and Saudi Arabia are the French cultural organisations which, faced with lower public subsidies, are delighted to find new sources of finance. Nathalie Coste Cerdain, the director of Fémis, told Mediapart about the film training given to around ten Saudi nationals. “This exercise takes place over the summer when the school has less going on. The students discover the particular nature of French cinema. We instil professionalism while at the same time opening their imaginations,” she said. But are all topics on the table? “We don't speak about the political situation,” she admitted. The amount of money that Saudi Arabia provides to Fémi each year is 100,000 euros, not a negligible sum for training around ten students over a period of days in the summer.

Both the Opéra de Paris and the Pompidou centre in Paris simply told Mediapart that their partnerships were not “active”. The INA did not respond at all to Mediapart's request for an interview. The reason for this reticence is simple: this kind of partnership does not make for a good press. In Italy, for instance, the decision of the former director of La Scala opera house in Milan, Alexander Pereira, to put the Saudi culture minister on its board in exchange for patronage from the Saudis caused a major controversy. Under the pressure of public opinion the project was dropped and the director's contract was not renewed.

At Afalua, however, there is rather less reticence in talking about these partnerships. “We're planning to build a museum of modern art with the Pompidou Centre. And with the Opéra de Paris, the idea would be to organise performances in the desert,” it said. The bosses of the biggest French cultural institutions, from the Château de Versailles to the Pompidou Centre, also went to Al Ula in January 2019. “The cultural world showed that it was not boycotting Al Ula after the Khashoggi affair,” a source close to Gérard Mestrallet said with satisfaction.

Mestrallet uses his network of contacts, for example with the Opéra de Paris where the president of the governing board is Jean-Pierre Clamadieu, who happens to be Gérard Mestrallet's successor as chairman of the board at ENGIE.

Saudi petrodollars are not just seducing cultural organisations but artists too, many of whom are profiting from this new windfall. The winter festival at Al Ula this year will, for example, feature the renowned French violinist Renaud Capuçon, the Capitole Orchestra from Toulouse in south-west France and musician Jean-Michel Jarre. And each weekend a leading French chef organises a dinner at the site, from Yannick Alléno to Hélène Darroze.

Intellectuals are also making the trip, for example the writer Jérôme Garcin, who is head of the culture section at L'Obs weekly magazine and who went in early February this year. These guests' expenses are paid for by their Saudi hosts. It makes it hard for them later to give a critical view on one of the most repressive regimes in the world.

In March 2020 the Saudi regime is also organising the first cinema festival to be held in Jeddah, with Jack Lang as a key guest. The former culture minister told Mediapart he will not be alone. “The guest of honour will be [French actress] Juliette Binoche,” he said. This is the same actress who in 2016 was part of a support committee for the poet Ashraf Fayadh, who had been sentenced to death for apostasy. Today some artists have no qualms about performing in that country, and are even happy to be taking part in its culture awakening.

All this is proof that the Saudi kingdom's public relations machine is doing its job. Meanwhile French commercial and business interests can rub their hands in anticipation. “We're at the planning stage,” Afalula told Mediapart about the future of the historic site. “But from 2023 there will be some major facilities at the site.” Large French construction firms such as Bouygues, Vinci and others have already put themselves forward. Via the medium of culture, French economic interests are now lining up with Saudi geopolitical imperatives. It helps one understand the meaning of the name of the university chair at the Sorbonne in Paris which has been funded by Saudi Arabia: “Chair of Dialogue between Cultures.”

-------------------------

If you have information of public interest you would like to pass on to Mediapart for investigation you can contact us at this email address: enquete@mediapart.fr. If you wish to send us documents for our scrutiny via our highly secure platform please go to https://www.frenchleaks.fr/ which is presented in both English and French.

-------------------------

- The French version of this article can be found here.

English version by Michael Streeter