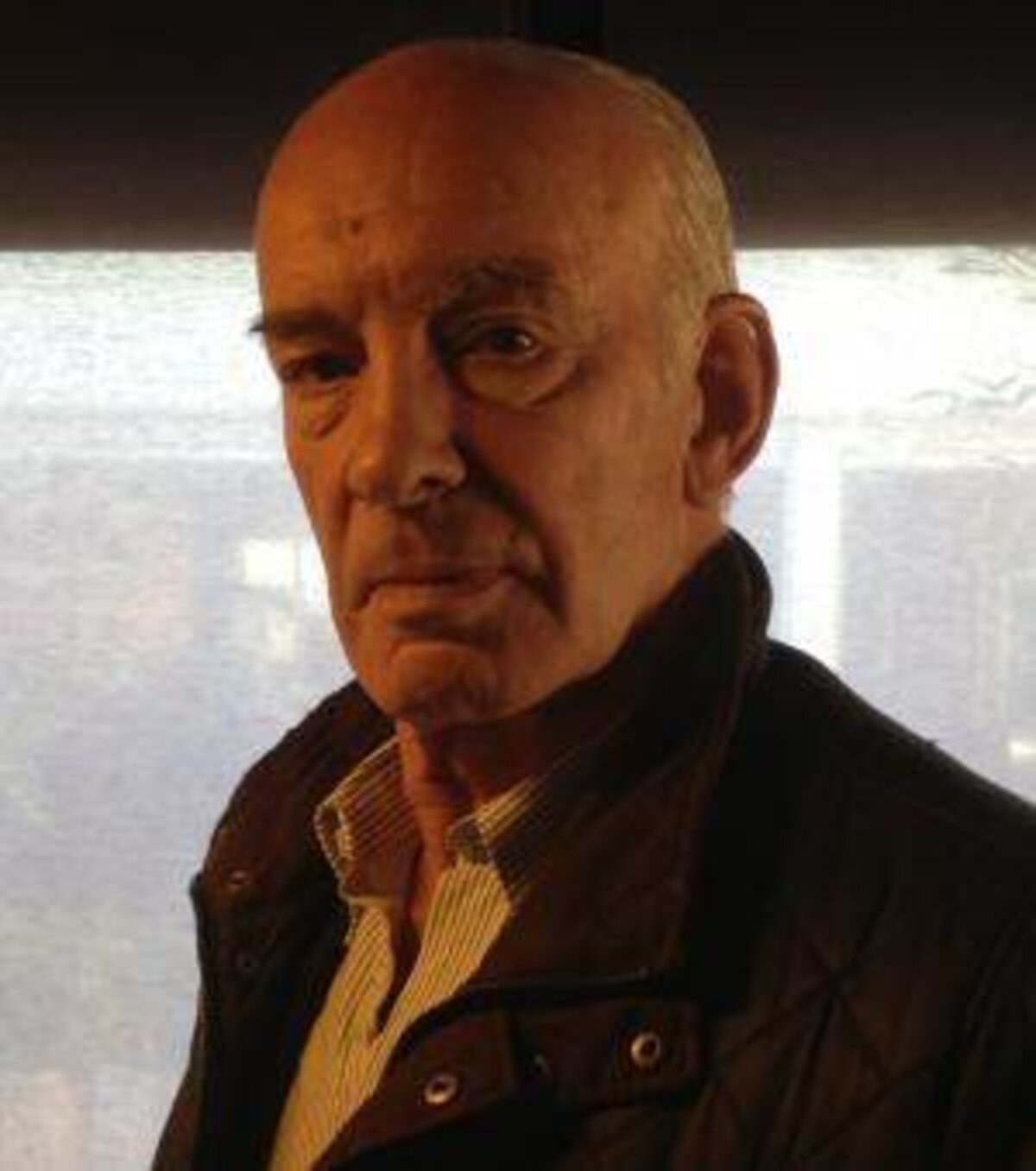

José Amedo Fouce says that it is high time former French interior ministers were publicly called to account over what they knew of French police participation in the four-year campaign of murders, bombings and kidnappings organised by the Grupos Antiterroistas de Liberacion, the GAL, between 1983 and 1987.

The former Bilbao deputy police commissioner offers a first-hand account of the covert French police involvement in the GAL, which was financed by the Spanish government and organised by the Spanish police, in his second book on the organization, Cal Viva (‘Quicklime’). Amedo Fouce was himself sentenced in 1991 to 108 years in prison, later reduced to 12 years, for his own role in GAL operations, which were first exposed by the Spanish press, and notably by the national daily El Mundo.

His own testimony in the subsequent Spansih judicial investigations and trials of GAL leaders led to the convictions of Julian Sancristobal, civil governor of the Biscay province, that of Rafael Vera, head of the Spanish state security department, and of Spanish interior minister José Barrionuevo. In 2009, Vera was found guilty of using 1.5 million euros of funds hidden in Switzerland to buy the silence of Amedo Fouce and other GAL operatives.

In Cal Viva, Amedo Fouce, now aged 67, reveals how a ranking French border police (PAF) officer, Guy Metge, who served as a key intermediary between the Spanish authorities and the mercenary French police agents who joined in assassinations for the GAL, was himself murdered by the organization to prevent him being questioned as a French judicial investigation closed in on him. Until now, Metge is officially recorded as having died in a car accident.

Enlargement : Illustration 2

He also identifies two other senior French police officers of being involved in the killings; Jacques Castets who served as an inspector in the town of Bayonne, south-west France, and Pierre Hassen, an officer with the PAF. Castets died in 1993, while a French judicial investigation into the role played by Hassen, whose handwriting was found on lists of names of Basque separatists given to the GAL, ended when the case against him was dismissed in 2006.

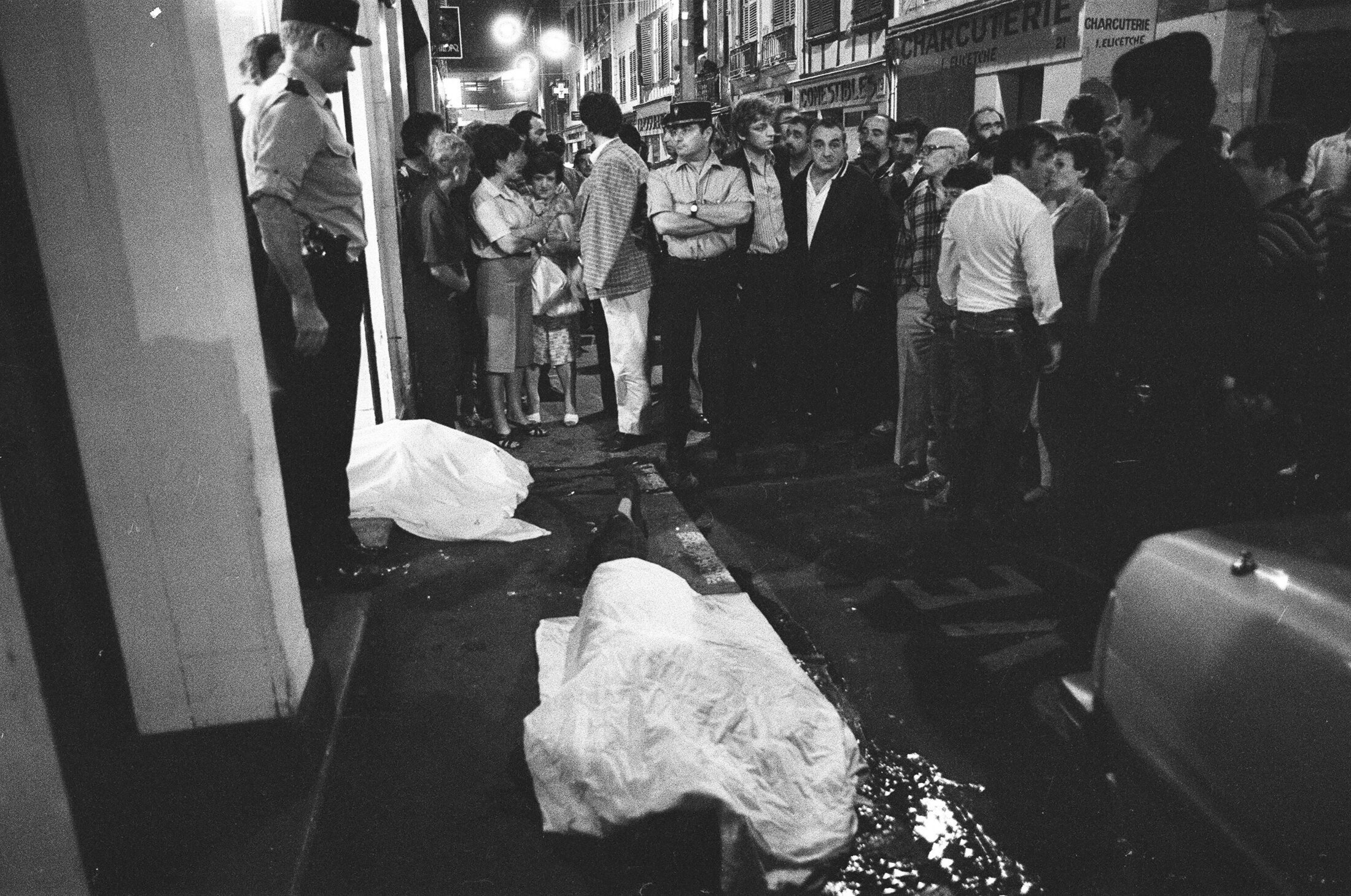

Amedo Fouce notably reveals the role of another, mysterious French police officer known only, according to him, by the first name of Jean-Louis, and who led hit squads on the ground in a series of attacks, notably that on the Monbar hotel in Bayonne on October 25th 1985 which left four people dead.

In France, investigations into the dirty war led by the GAL have resulted in the convictions of a handful of operatives, without ever identifying those who organised the French participation in the terror campaign. Most are now protected from prosecution under the French statute of limitations law, which notably bars the opening of an investigation after ten years or more have passed since the crimes were committed. During the trial in Spain in April 2011 of former Bilbao police officer Miguel Angel Planchuelo, which ended in his acquittal of charges of serving the GAL, the public prosecutor, Pedro Rubira, underlined that the role of the French policeman and GAL operative ‘Jean-Louis’ was “worthy of being elucidated”.

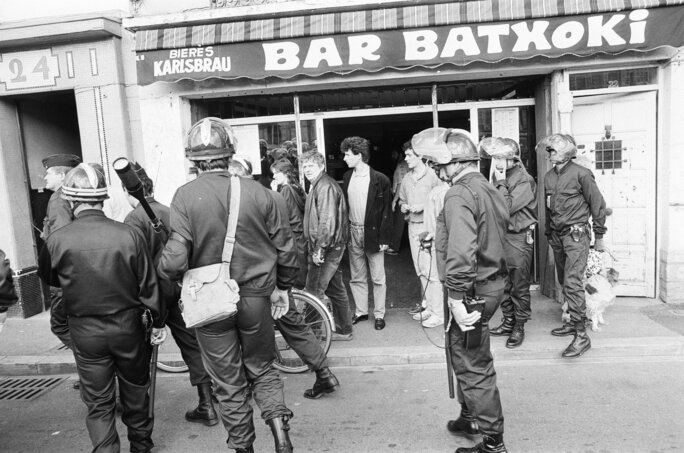

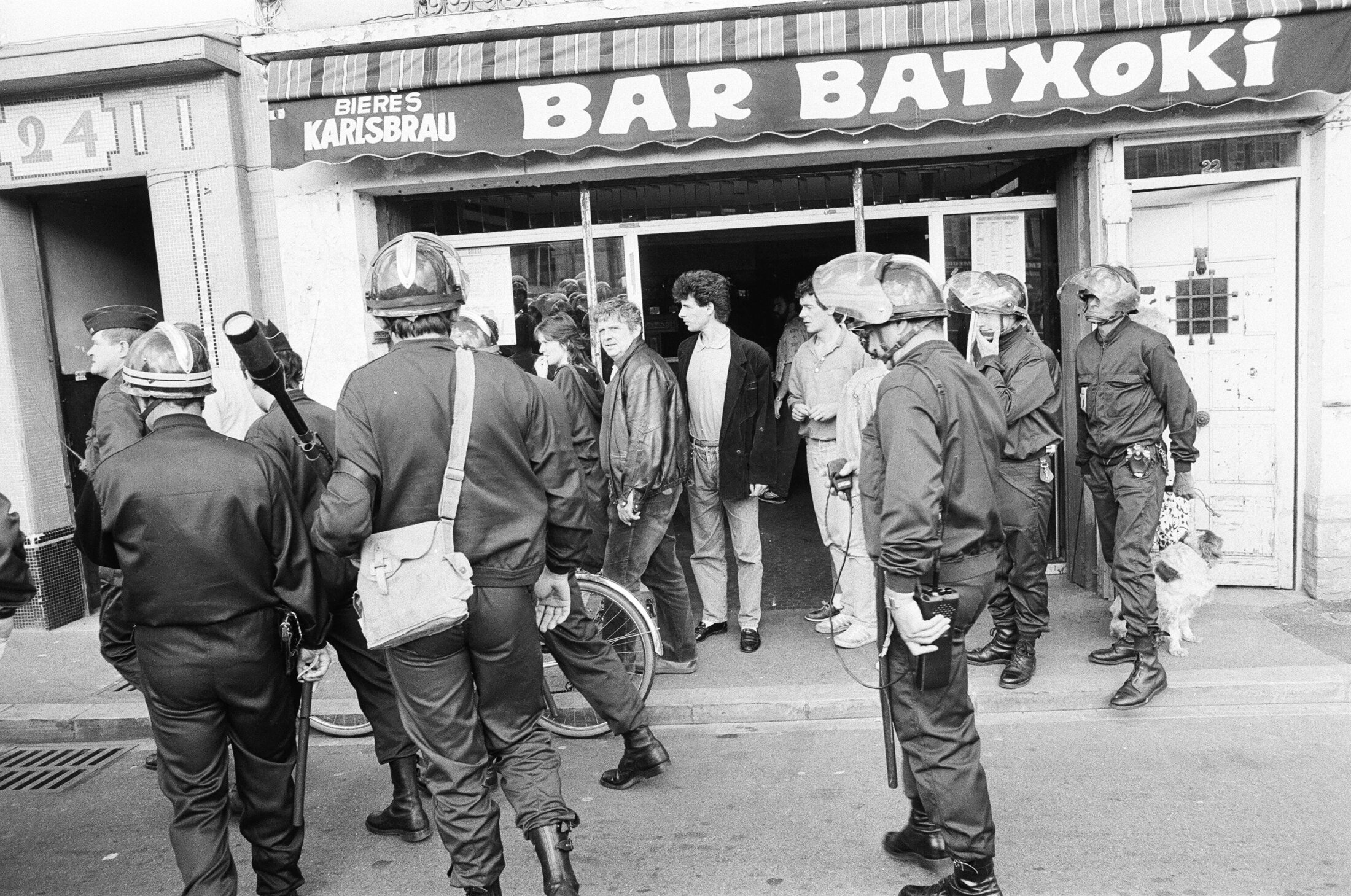

Enlargement : Illustration 3

During the trial, the public prosecutor’s office cited the involvement of ‘Jean-Louis’ in the shooting and wounding of six people, including two children aged four and five, in the Batxoki bar in Bayonne on February 8th 1986, when he allegedly identified the targets and provided the hired Portuguese hitmen with their arms.

According to Amedo Fouce, high-placed French officials regularly passed on information to their Spanish counterparts to protect GAL operatives from being arrested in France.

He adds further detail to all these accusations in this interview with Mediapart, in which he begins by explaining the history of the French police involvement in the GAL.

-------------------------

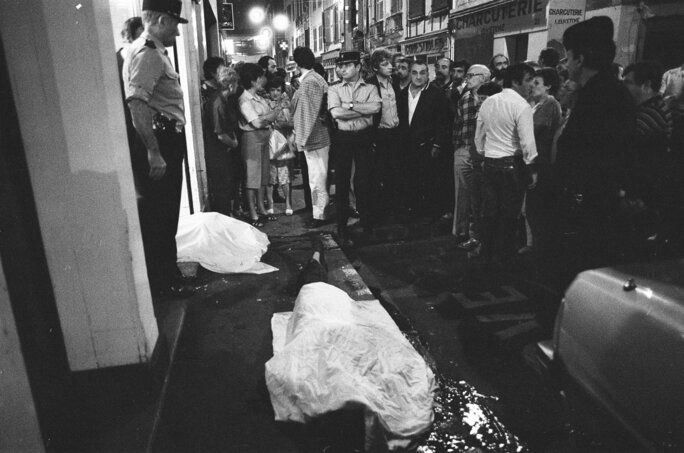

Enlargement : Illustration 4

MEDIAPART: It was known that the GAL was an organisation set up by the Spanish government, but now we discover that there was a clandestine French structure to it. One has the impression that the GAL could not have operated without this help.

Jose Amedo Fouce: Never. Everything would have been much more complicated. Because in such a small zone, to operate with the backing of a structure made up of French professionals who know where members of ETA are found - who follow their movements, who know their weak spots - simplifies the roadmap. There were operations we organized from one day to the next, and this was precisely thanks to the involvement of French police, who made the GAL much more operational.

MEDIAPART: In the beginning, there was a decision taken at the highest level by the Spanish Socialists, who gave the order to begin action.

JAF: Before coming to power, Felipe González already had this idea in mind. Let me remind you what he said – before becoming president of the government [prime minister] – to left-wing journalist Martin Prieto. ‘What do you say if we kill them?’. He knew that the new Spanish democracy would remain fragile if the forces of law and order continued to be inoperative towards ETA.

ETA, which killed military personnel with regularity, drew its force from the possibility of entering France and hiding its commando members there after their actions in Spain. González asked for help from [French President François] Mitterrand, who refused him. So they took this decision.

After the definitive meeting in Madrid, where the agreement to launch the operations in France was formalised, I met Julian Sancristobal, who later became the general director of state security, in his office. He explained to that it was a government operation decided by Felipe González. And that this decision was taken because democracy was in danger. The choice surprised me, but I shared it. In Spain, 90% of the population would have approved it, given that there were deaths every week and without any result from us.

Enlargement : Illustration 5

Sancristobal knew that I had a network of collaborators in France, essentially informants. I set it up for very simple reasons. Having arrived in Bilbao at the age of two, I was completely integrated, by my accent, my localization, at the core of the Basques. The police who came from outside the Basque country stayed, out of fear, in their barracks or police station. They didn’t even have the thought of crossing the French border, which I crossed as if it was the most natural thing in the world.

At the time, I had prepared a meeting, at the property of a local businessman, Pierre Guerracague, between some political figures and the leaders of ETA’s ‘polimili’ tendency [which placed priority on reaching a political solution for their aims] so that negotiations begin. Everything was ready when it was decided, at the very highest political level in Madrid, to go and kidnap and kill ETA members in France.

MEDIAPART: So you began recruiting in France?

JAF: What Sancristobal asked of me in his office was to mobilize this network of French police officers, who earned more money with what we gave them than what the French state paid them. It was a question of buying goodwill. People linked to the antiterrorist fight gave us in secrecy the files concerning the members of ETA arrested in France, which was very well paid for. In [the French Basque region towns of] Bayonne, Saint-Jean-de-Luz, Biarritz,I had a network of police, I’m talking about a certain number. We invited them also to Spain, to have a good time, to meet up with prostitutes, [to do] what they felt like.

MEDIAPART: One of these police officers, ‘Jean-Louis’, played a key role. It was Guy Metge, a member of the French border control police, la police de l’air et des frontières, who introduced him to you?

JAF: Yes. In the beginning, I explained to Guy Metge, what we planned to do in France and he and the others began to activate themselves. There was a need to continue with the passing on of information but at the same time to prepare for the new operational framework. He introduced me to Jean-Louis. He presented him to me with this first name, but I don’t know if this corresponds with his true identity. He was someone who took many precautions. He was cold, calculating, devious, very competent. He asked if we could mount an attack against a member of [French Basque nationalist paramilitary group] Iparretarrak. After a study, we told him yes.

[Editor’s note: one of the first terror attacks organised by ‘Jean-Louis’ was against Iparretarrak leader Xabier Manterola, on February 1st 1985.]

Jean-Louis presented himself as a police inspector. He told me that Iparretarrak had killed one of his comrades. He was the most operational among the French who joined in the action with us. He acted with ease, with a workforce that he brought along himself. Metge continued to work, but Jean-Louis took the lead over everyone else through his operational capacity.

MEDIAPART: At what moment did his involvement appear to you to be decisive?

JAF: In October 1985, Jean-Louis set up an operation that was intended to cause a determined number of victims. He had localized three ETA members in a bar in Biarritz. Before beginning the operation, he was supposed to call here, by telephone. He called Spain. But we said no, there must be at least four targets. We wanted a more spectacular operation. On the ground, the shooters who were already in position,Lucien Mattei and Pierre Frugoli, stood down. As of the following day, Jean-Louis took up position with his gunmen on the rue Pannecau, in Bayonne, with his new instructions, and he attacked the Monbar [hotel]. He had answered our demands in the space of a few hours. The commando group left four dead.

Enlargement : Illustration 6

MEDIAPART: Was the phone call to Spain a systematic procedure?

JAF: The ‘OK’, yes.

MEDIAPART: To whom?

JAF: Someone called the Ministry of the Interior. In a case like that, for example, everything was chronologically organised. One made a call before. It was a question of seconds. We warn that something is about to happen, ‘everything is in place, it’s ready, here’s waht’s going to happen’. A few seconds before, we analyse the number of victims. For the politicians, those who lead the GAL, Sancristobal and above, the collateral damage ended up being included in the operations.

Sancristobal wanted to blow up booby-trapped vehicles in France, something that implied the deaths of numerous people. If we caused collateral damage, we made French public opinion, French Basque here, much more concerned, and the authorities in the zone, to influence Paris.

MEDIAPART: So collateral damage was acceptable?

JAF: It was accepted. The objective was to spread fear and instability in southern France.

Enlargement : Illustration 7

MEDIAPART: One can suppose then that behind these calls came a political decision for each operation?

JAF: Yes. Julian Sancristobal, Rafael Vera... one of the two, logically in agreement with the interior minister and the prime minister, was informed of what was going to happen. It’s simple.

MEDIAPART: At a superior level, was this type of information transmitted between the Spanish and the French?

JAF: From an official standpoint, there was a great friendship with French officials, and also envelopes [of money]. The same thing as me, in the field. I had information because I had people. [Former Spanish police officer]Jésus Martínez Torres also gave money to the head of the anti-terrorist fight in France who, in return, gave him information. An example: the French police, in agreement with a French magistrate, had planned to wait at a given place to arrest us. A French anti-terrorist head called Martinez Torres to warn that our appointment at the French border had been uncovered. And Martinez Torres phoned [Bilbao police chief] Miguel Planchuelo who told me ‘don’t go there because they’re going to arrest you’. We were warned to the danger from above. That well confirms that there was an involvement at a high level to hide those things.

MEDIAPART: After the Monbar attack, the French police collected photos taken by passers-by, believing that some involved in the attack had remained in the area.

JAF: Jean-Louis was very close to there. He even announced by telephone the moment when the attack on the Monbar began. ‘It looks like they’re armed inside, because there’s a gunfight, and it’s like they’re letting off fireworks in Bayonne’.

Enlargement : Illustration 8

MEDIAPART: One of the most mysterious episodes of this terror campaign remains that of the involvement of two young women in the GAL operations, who were nick-named 'the Dama negra' and 'the Dama rubia' and who were prepared by, and closely linked to, Jean-Louis.

JAF: In March 1985, the first operation of the Dama negra was led by [French police officer] Jacques Castets. She burst into the Lagunekin bar, on the rue Pannecau [in Bayonne], through a back door. She seriously wounded two ETA members. Then it was indeed Jean-Louis who took charge of her. When I was told about her for the first time, I asked myself who was being spoken about. It was during the Foreign Legion celebrations in Bayonne. Dominique Thomas, the Dama negra, had had a military training, she was of Vietnamese origin and the daughter of a French military man. The other young woman, the rubia, called Margaret, was trained by Dominique

MEDIAPART: You have now revealed a photo of the Dama rubia. She was never identified.

JAF: Never. I have her last name and her first name.

Enlargement : Illustration 9

MEDIAPART: Doesn’t the participation in operations by these hardened female killers in fact reveal the involvement at the core of the GAL of the secret services?

JAF: Money, in fact, wasn’t something that was important for them [the women], they took it without any discussion. They were impressive, those girls. Especially the first, Dominique, when she was in action in the Lagunekin bar, with the mystery she left behind her, and the terror she caused for the ETA members. To see a girl, of small stature, burst in with an automatic pistol in her hand, on the rue Pannecau which was a bastion, the epicenter for ETA, a very narrow street from which there is virtually no way out…These girls were well prepared, they disguised themselves, leaving their disguise behind them at the scene. On one occasion, to play the game a bit harder, she left her wig on the body of one of her victims. Without any doubt, to be able to carry out this type of action, you have to be very psychologically prepared. And in fact, they were never caught [for murder], even if Dominique was charged. She was made to try on the shoes left at the scene by the blonde, which cleared her.

Enlargement : Illustration 10

MEDIAPART: In 1991, Dominique Thomas was sentenced to just five years in prison for criminal conspiracy.

JAF: Yes, and at the same time there’s a man still imprisoned in France,Jean-Philippe Labade, for having taken part in the GAL in a minimal role, as an informer. The life imprisonment sentence he was handed is one of the greatest injustices committed. I find it terrible that he would have lost his life in prison for such a small responsibility. Labade’s mistake was in knowing Patrick de Carvalho, one of the GAL’s gunmen, when he was on the point of going into action. Because he [Labade] sold commercial property, he gave him the keys to a place in Ciboure, which was where it had been chosen to target an ETA leader. Carvalho was preparing to carry out the attack with a crossbow, to land an arrow in his face with the symbol of the GAL on it. Because the police were just behind [to capture] Carvalho, when they found Labade they thought he played a major role in his [Carvalho’s] actions.”

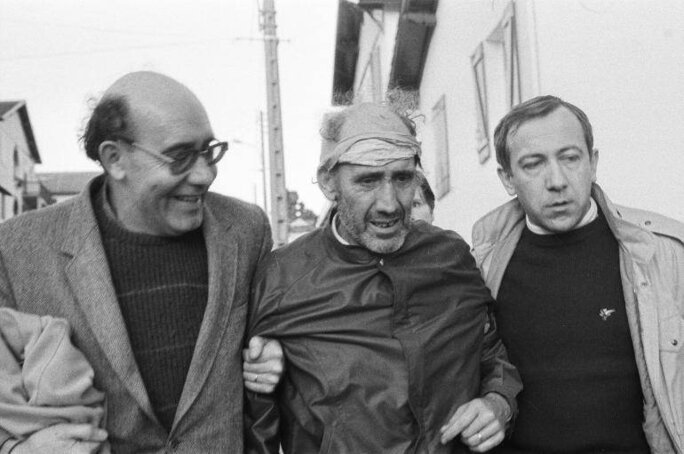

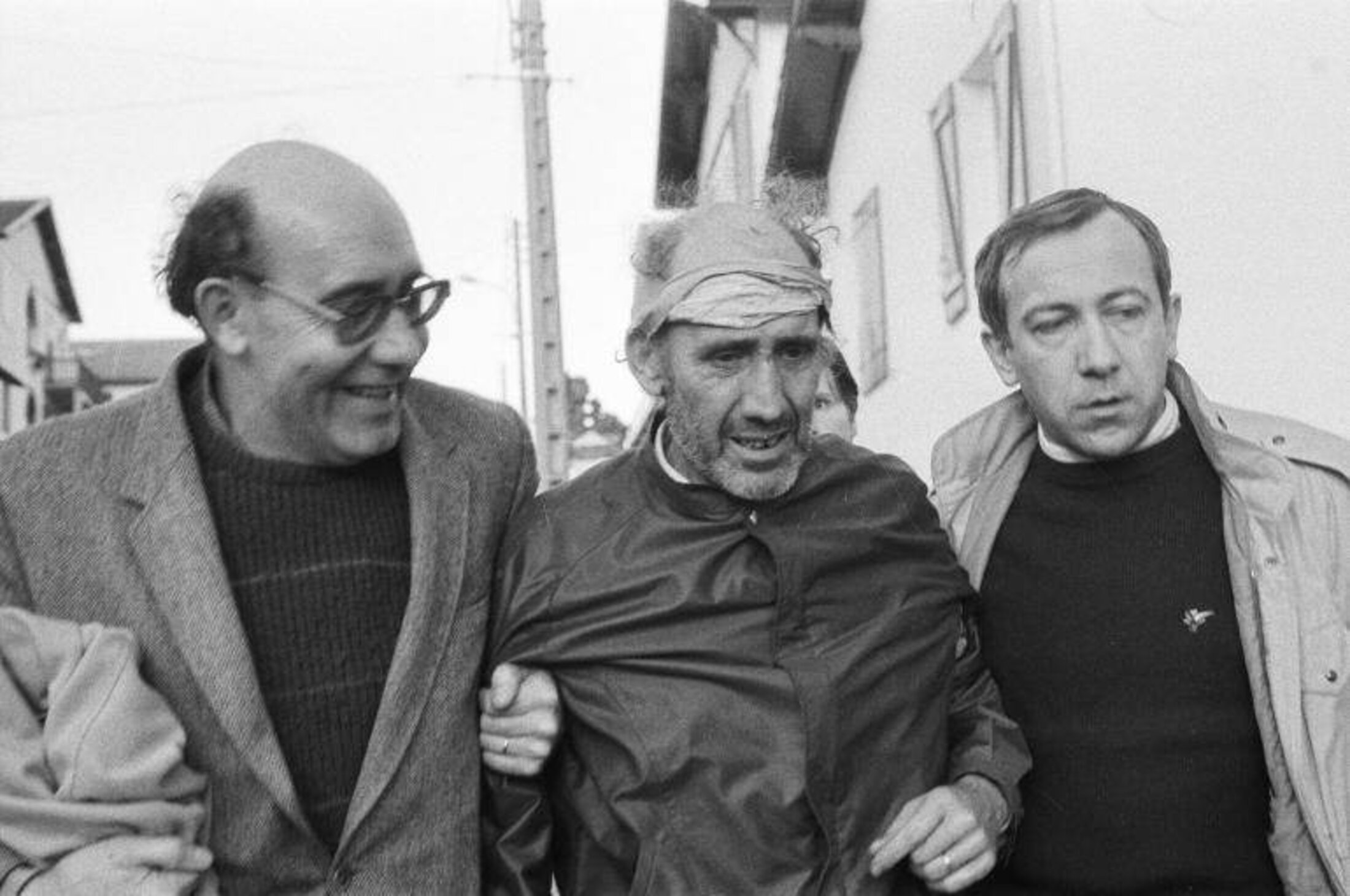

MEDIAPART: During that same case, the investigators became suspicious about the involvement in the GAL of French border control police officer Guy Metge.

JAF: Labade had Guy Metge’s phone number. As a result, there was suspicion about Metge, and someone decided that he should be eliminated so that France did not become implicated in any judicial case.

MEDIAPART: It is Jean-Louis who told you they had killed Metge, whereas officially he died in a road accident?

JAF: That’s true. They did with a set-up which blocked the gearbox. Jean-Louis wasn’t any clearer than that. I don’t know who carried out the operation. At the higher level, the French and Spanish services did everything possible so as not to appear involved in this affair.

MEDIAPART: You have published the photo of a man identified as ‘Jacques’ and who appears to have been the group’s explosives engineer.

JAF:Yes, Jacques was the technician for that subject.

MEDIAPART: You say that at the end of the terror campaign, Julian Sancristobal, the civil governor of the Biscay province, said to you ‘About Jean-Louis, you don’t talk’. Did Sancristobal have a direct contact with ‘Jean-Louis’?

JAF: Yes. I got to know they spoke together. There was something happening. Sancristobal intervened directly in certain operations. He was very impetuous. He, a political figure, came to the scene of the kidnapping of Segundo Marey [Editor’s note: Marey was kidnapped by the GAL in south-west France in December 1983, but was a mistaken target, having in fact no links with ETA]. He met the members of the commando. He held talks with [GAL mercenary] Mohand Talbi in the mountains when Marey was kidnapped, to stimulate him. Sancristobal involved himself a lot. A lot. He used to say ‘I want blood’, he wanted there to be deaths in France.

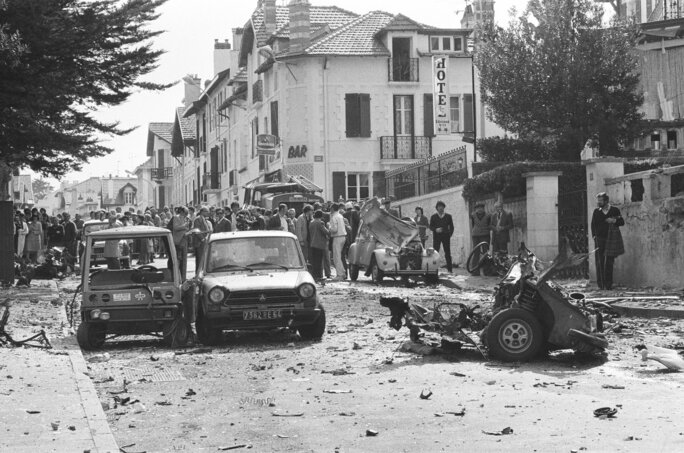

Enlargement : Illustration 12

Initially, in 1983, he went and found a delinquent, Morcillo, to have somebody killed in Spain. Sancristobal was also the initiator of a plan for a car bomb in [the south-west French town] Saint-Jean-de-Luz targeting the Mingo bar, which was frequented by ETA members. A bomb made up of three kilos of dynamite and two kilos of nails was given to a GAL man, Jean-Pierre Echalier. With that, the whole building could have been brought down. In the end, Echalier pulled out and we never saw him again, and the operation was wound down.

MEDIAPART: Exactly how high does the chain of decision-making reach?

JAF: In Spain, it’s a decision taken at the highest level, and of which the king is informed. Don’t forget that after the attempted coup d’état in 1981, the military demanded that action be taken against ETA in France. If that had not been taken to the highest level, it could never have happened.

MEDIAPART: Until now, Felipe González has denied this.

JAF: One or two years ago, González said ‘I could have blown up the leadership of ETA in France’. That’s the beginning of saying something. Everyone knows that González was behind it. And at the moment when ETA is going to dissolve itself, and lay down its arms, logically ETA and the [Basque Nationalist Party] PNV will demand that the Spanish state recognizes that we also acted against them by executing them. They will ask for this. Today’s [People’s Party] government won’t recognise it, because Manuel Fraga Iribarne [deceased former founder of the People’s Alliance that became the People’s Party] was informed by Felipe González.

As was also the king. The king called Judge Garzón [who led investigations into the GAL] that he shouldn’t investigate the GAL because it was a governmental subject. I believe that [former head of the Spanish state security department] Rafael Vera will tell about this when the ETA page is turned. And I think that González will too.

But careful, French ministers of the interior must also tell, that they tell about what they knew of. In prison, Sancristobal tol me that when he was state secretary, a leading member of the French special services, with whom he was a friend, had obtained the recording of a meeting between Felipe González and François Mitterrand on the subject of the GAL. In substance, Mitterrand asked him to cease operations.

At the superior level, the French government knew that the Spanish government was behind the GAL. And when [Jacques] Chirac came to power in 1986 [Editor’s note: as Prime Minister under Mitterrand], he said to González ‘this business is over’. After that, during the judicial investigations, the French were warning ‘Don’t come here because we’ll catch you’. In this manner, the collaboration continued. The French state also protected the GAL.

MEDIAPART: Why did you entitle your book Cal Viva?

JAF: I didn’t think of publishing this book with the 30th anniversary of the GAL in mind, but rather the end of the first operation. [ETA member José Ignacio] Zabala and [fellow ETA member Joxe] Lasa, who were kidnapped in Bayonne, were buried in quicklime near to Alicante. They had thought of reserving the same fate for Segundo Marey, I was against this. They had already bought the quicklime.

-------------------------

- The black and white photos featured in this article are by Daniel Velez, a photographer who covered the terror attacks in France's Basque region during the 1980s for French regional daily Sud-Ouest and as a correspondent for press agency AFP.

- This interview with José Amedo Fouce was originally conducted in Spanish, and translated into French.

-------------------------

English version by Graham Tearse