It’s a modern district in an old town, a sad zone amid a metropolis that is full of life. Here and there are incomplete concrete structures sitting among the brand-new glass-fronted buildings. The ACI 2000 district of the Malian capital Bamako, built during the first decade of the 21st century, was supposed to represent a radiant, forward-looking country. But today it is a sorry pseudo-modern growth on the face of the capital, full of abandoned building projects and whose inhabitants complain it is unliveable.

“A certain number of investors, Malian and foreign, used it to launder money, to the point of abandoning buildings under construction,” said Hamadou, a guide belonging to the Dogon people of central Mali, who settled nearby ACI 2000 after security fears led to a collapse of tourism in his native region.

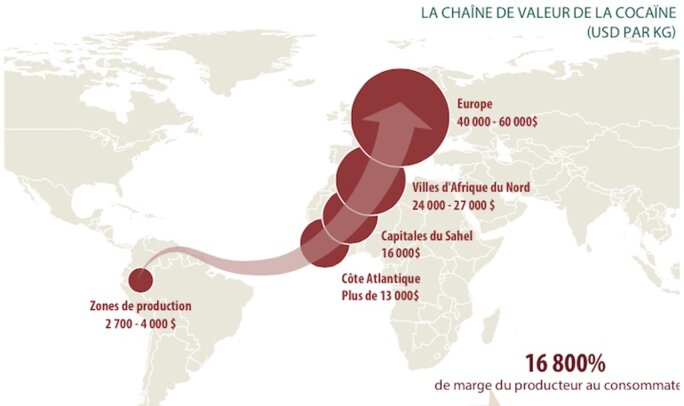

Enlargement : Illustration 1

The 2012-2013 crisis in Malian, one of the world's 25 poorest countries, and the errors that preceeded it, are the result of a multitude of elements: weakened elites, a lack of insight on the part of the international community, the incompetence of the Malian army, Islamic terrorism, the collapse of post-Gaddafi Libya, and the Tuareg separatist movement. But there is another element, which is one of the least often cited and which is part of the backdrop to every dysfunction in Mali; it is the West Africa drugs trade. In 2012, before French military intervention in the country, Mali had become a hub for the transit route of drugs between South America and Europe and, according to most experts, it has again today.

Pierre Lapaque is the representative of the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC) for West and Central Africa. He says that the 18-month French military campaign, Operation Serval, launched in January 2013 to neutralize Jihadist forces and to liberate the north of the country, had the side-effect “for about one year” of scattering the drug trade routes into neighbouring countries. “But today,” he said, “the routes that were closed down because of the presence of helicopters or patrols have been reopened.”The main difference is that whereas before the drug traffickers would move a tonne of drugs in one go, now they transport smaller single amounts to reduce losses if caught.

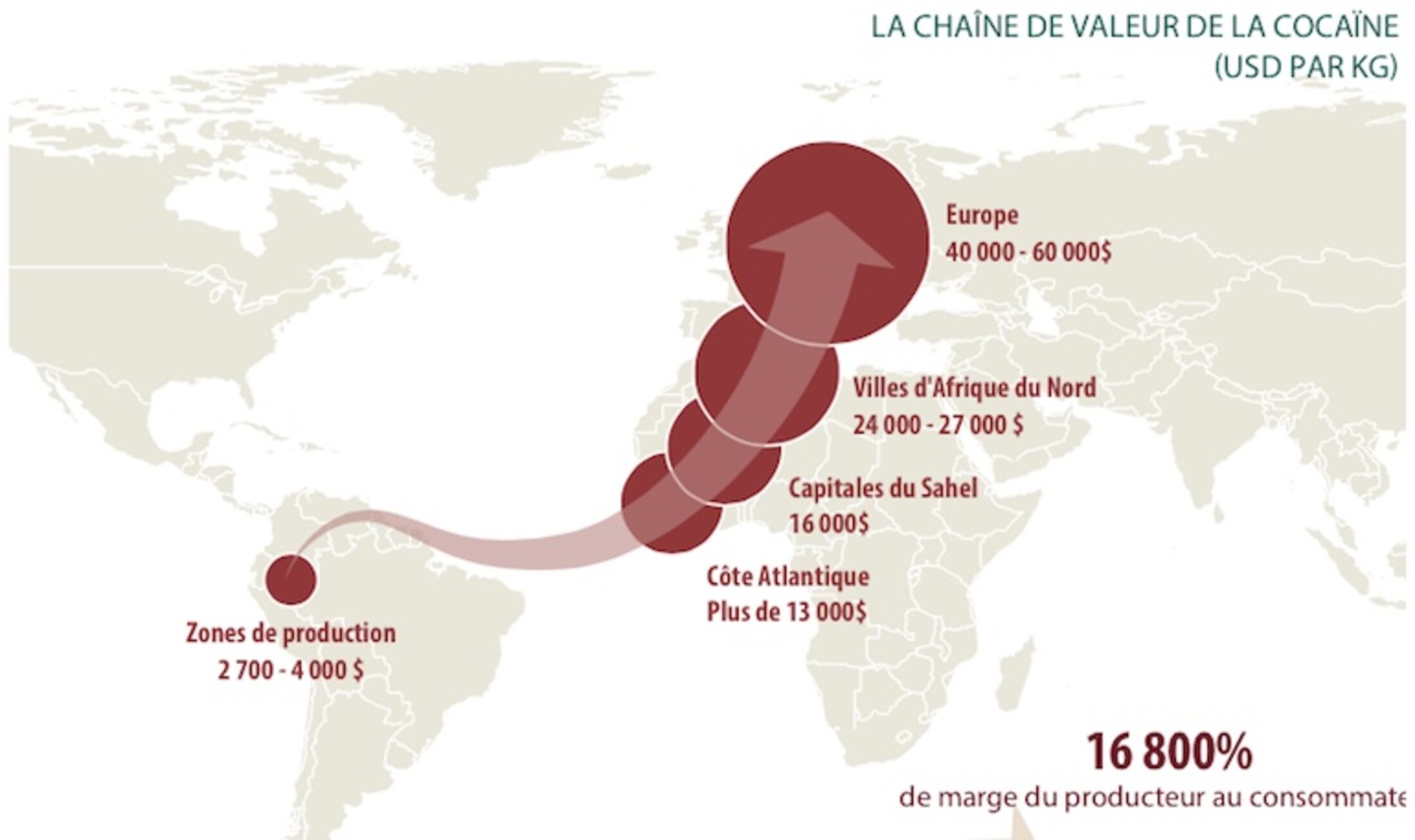

The story of smuggling across the Sahel, from Mauritania and eastwards to Chad, goes all the way back to the 7th century. More recently, it has operated in an opportunist manner, the wares ranging from contraband cigarettes and medicines to arms and migrants. Drugs are just one type of clandestine merchandise, but also the most profitable and which has had for effect an increase the corruption and destabilisation of countries in the region.

Mali is just the latest illustration of this phenomenon, which became significant in the early 2000s. An emblematic example of this was an event that took place in 2009 in desert land close to the town of Tarkint, near Gao in northern Mali. That was where a burnt-out Boeing 727 was found on a makeshift runway in the desert to where it had flown from Venezuela. The cargo plane had managed to land intact but once emptied of its cargo of several tonnes of cocaine it was unable to take off for its return flight, so the traffickers set fire to it. It was a transport method that became known as ‘Air Cocaine’.

Enlargement : Illustration 2

“‘Air Cocaine’ was a period of large shipments, much more risky,” said Pierre Lapaque. “Today, the traffickers divide up their cargoes.” That change of tactic not only reduces potential losses, but also avoids the attention drawn by events like the discovery of the burnt-out Boeing 727, which prompted suspicion that there was connivance in the drug operation by senior Mali state figures, as illustrated in cables from the US embassy in Bamako revealed by Wikileaks. “You don’t land an aircraft in the desert without a minimum amount of local complicity,” commented Georges Berghezan, a researcher on conflicts in sub-Saharan Africa with the Brussels-based independent research centre, the Group for Research and Information on Peace and Security. “People close to Amadou Toumani Touré,the former president, were involved in the traffic.”

Fast-growing consumption of methamphetamines

According to numerous diplomatic and academic sources, a number of those who made up the Malian elite during the presidency of Amadou Toumani Touré received bungs from the drugs traffic that transited through Mali. “The military in particular were very mixed up in the traffic, either by closing their eyes, or sometimes protecting the [drug] convoys,” said a member of the diplomatic staff of the Bamako embassy of a major Western power, and whose name is withheld. “But there are also civilians, “he continued. “It is they who, sometimes, pay bribes to get across borders, who provide vehicles and so on. It is also they who launder the money, either via local development projects, which are more or less crap, or via the purchase of strips of land or of property, like ACI 2000.

"The big trafficking issues are around the intersection of very poor, very weak, very corrupt, and often very fragile states with state participation in various forms of criminality," said Brookings Institution senior fellow Vanda Felbab-Brown, cited in a report about the West African drugs trade by the organization Stop the Drugs War. "Drugs are just another commodity to be exploited by elites for personal enrichment. Elites are already stealing money from oil, timber, and diamonds, and now there is another resource to exploit for personal enrichment and advancement." The collapse of the Malian state in 2012 and its current weakness cannot be explained as solely due to the drugs trade, but it has certainly played a significant part.

The UNODC estimates the value of the drugs trade across West Africa at about 1 billion dollars (800 million euros, of which about half, it believes, is laundered in the region), which is almost the GDP of Guinea-Bissau, a quasi narco-state and the principle point of entry for drugs in the region. “There is a real threat of impact upon the democratic principle of these countries and the governance of states,” said the UNODC representative Pierre Lapaque. “How can a lowly civil servant who earns a few dozen euros per month resist bribes of several thousand euros?”

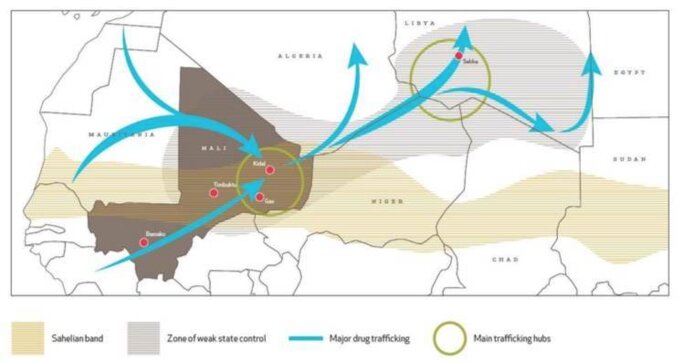

Enlargement : Illustration 3

The growth of the drugs traffic in West Africa is an issue of concern for international organisations, notably because a part of the Europe-bound transiting drugs from South America end up remaining in the region. Of the 30 to 35 tonnes of South American cocaine that arrive annually in West Africa - by boat and small planes which land in the bush - about 18 tonnes are shipped on to Western Europe along land routes that cross Mali, Mauritania, Niger, Algeria, Libya, Chad, Sudan and Egypt. Pierre Lapaque says that of the 12 to 17 tonnes that stays in the region; “Part of it is stored, so as to maintain stock supplies and therefore prices, but the other part is sold on site, because the criminal groups need new markets. Now, what better market than an expanding Africa?”

Beyond the problem of cocaine, which remains expensive, the major preoccupation is methamphetamines, of which an estimated 1-1.2 tonnes of this addictive neurotoxin is now produced in the region (where only it and cannabis are made locally). That is a significant amount given that there was no production eight years ago. While the methamphetamine production is mostly exported to South-East Asia, consumption of the drug in West Africa is fast-developing because of its relatively cheap cost. According to the ONUDC, a kilo of methamphetamines – which costs 7,000 dollars to make in clandestine labs – sells for 15,000 dollars in West Africa and for 150,000 dollars in Japan. Worryingly, the drug gangs have begun paying intermediaries in methamphetamines, instead of money, which the intermediaries then sell on the market. The expansion of the distribution of the drug threatens to make drug use, limited until now, a major health issue for West Africa.

West Africa commission eyes decriminalisation of drug use

For the time being, Mali remains a transit country for cocaine and methamphetamines. But it is significant that the drug transit routes have returned to Mali so soon after the rout of the jihadists, since when the French military operation has been succeeded by the United Nations Multidimensional Integrated Stabilization Mission in Mali (MINUSMA). “The hold of AQIM [editor’s note: al-Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb] upon northern Mali reduced the traffic by air from South America and Guinea-Bissau, said GRIP researcher Georges Berghezan. “But today the traffic is increasing again. The instability in southern Libya and the relative stabalisation in Mali has allowed the trafficking to take off again like in 2011.”

A member of the diplomatic staff of a Western embassy in Bamako, whose name is withheld, agreed. “Why do you think the Malian army is so keen to set itself up again in the north of the country?” he asked. “There is of course a degree of nationalism, but essentially the military personnel want to take back their place in the drug trafficking.” Another source, close to the Malian government but not a member of it, and whose name is also withheld, said that a recent scandal involving several contracts awarded by the defence ministry which were overbilled to the tune of about 45 million euros was prompted by the army’s “momentary loss” of revenue from the drugs trafficking. “Because the money from drugs dried up for a while, some in the army and among civilians in the defence ministry looked for other sources of revenue by means of embezzlement and over-billing,” he commented.

Enlargement : Illustration 4

Smuggling is both a historic and vital activity for the whole of the Sahel region. “We are either cattle breeders or traffickers,” half-joked a Tuareg militant who had sought refuge in Bamako after opposing jihadist forces occupying his region in the north of Mali. “AQIM [Al-Qaeda in the IslamicMaghreb] has always preferred hostage-taking, which brings in more, but [the AQIM breakaway group] Movement for Oneness and Jihad in West Africa [MOJWA] is involved in the drug trafficking. As for the other groups and the individuals themselves, including my Tuareg comrades, everything is a question of opportunity. I know people who, since 2012, have successively belonged to the Malian army, independence movements, to jihadist groups, and who then allied themselves with the French troops and who have now gone back to trafficking all they can find, electronics, migrants, drugs.”

Landlocked Mali is just a cog in a big wheel, by which the Sahel strip is the transit zone, and the Atlantic coast countries the points of entry and, to a degree, production. The beginnings of a local trade and consumption of methamphetamines means drugs will continue to destabilise the states in the region, as illustrated by the official launch in June this year of The West Africa Commission on Drugs, created on the initiative of former United Nations Secretary-General Kofi Annan, and whose first published report is entitled Not Just in Transit: Drugs, the State and Society in West Africa.

The report, prepared under the management of former Nigerian president Olusegun Obasanjo, who heads the commission, warns of the size of drug consumption in the region and its consequences on the democratic process in states. It also makes recommendations to address the problem, which include the decriminalisation of drug use. That argument aligns itself with the reflections of others in a number of countries, notably in South America, that anti-drugs policies exclusively based on repression have proved a failure. The exploration of the issue of decriminalisation is much more advanced in so-called southern nations than in a number of Western democracies, and for good reason: for the former, it’s become a question of survival.

-------------------------

- The French version of this article can be found here.

English version by Graham Tearse