On August 8th, an open-air screening of the popular film Barbie was cancelled under pressure from a small group of residents in Londeau, a poor neighbourhood of Noisy-le-Sec in the eastern suburbs of Paris. At the time the Communist mayor Olivier Sarrabeyrouse spoke of “threats” that had been “motivated by false arguments” which “came across as anti-intellectualism and fundamentalism being used for political ends”, and which had come from a “very small minority of thugs”.

When contacted by Mediapart on August 19th, the town hall said: “We didn’t want [these residents] to take the chairs and throw them, or for equipment to be damaged. Safety was the priority. And now, with hindsight, we should have said that it was intolerable, disrespectful, unacceptable.”

The cancellation of Barbie, reports of which was shared on social media, quickly became a major news story in early August. On August 13th, culture minister Rachida Dati criticised it as a “serious attack on the scheduling of events”, while the next day interior minister Bruno Retailleau condemned a “violent minority that wants to ‘halalise’ the public arena”.

Enlargement : Illustration 1

Growing number of cases

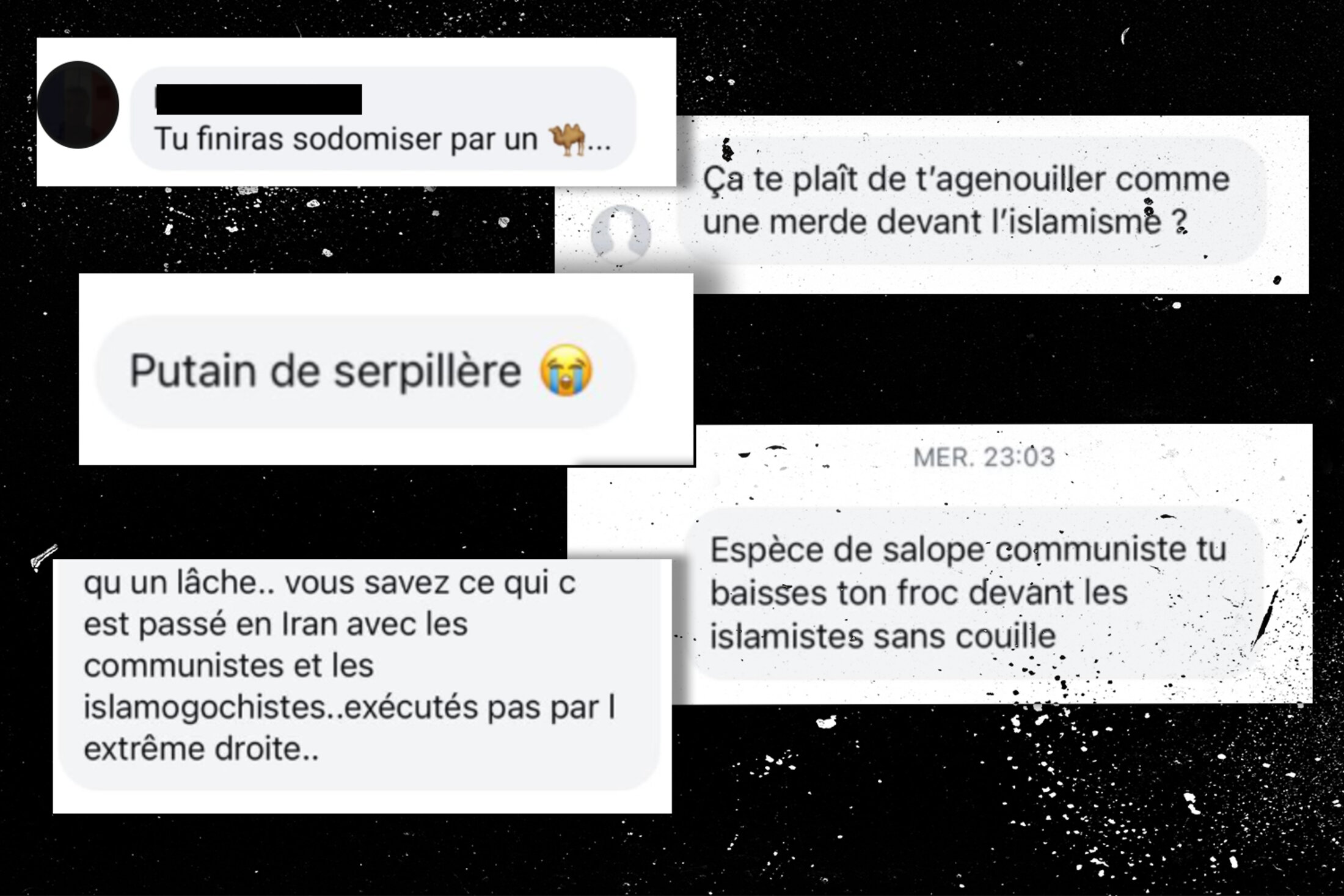

That same day, at a press conference, the mayor responded to these ministerial comments, saying: “While I always condemn with the same firmness the acts that I described as anti-intellectual and fundamentalism, I condemn even more strongly the political opportunism, and the speculation over racist Islamophobic hatred, that has been pouring out from the right and far-right for 24 hours.” The town's deputy mayor in charge of culture, Wiam Berhouma, added: “The reason this story has been blown up to such proportions is because the people involved were identified as Muslims and because the events took place in a working-class neighbourhood.” Since then the local council has been battling against a tide of racist and Islamophobic abuse on its social media. “We're overwhelmed. We actually had to block all comments,” the town hall told Mediapart.

Enlargement : Illustration 2

The Noisy-le-Sec affair is just the latest in a long list of assaults on the freedom to stage cultural and artistic performances in the country. Back in November 2016, a report by the French Senate had already highlighted what it termed a “major point of concern”. This was a “worrying rise in challenges to the principles of freedom of creation and artistic publication”. In a report sent to senators in August 2024 the Observatoire de la Liberté de Création, a body which fights against hurdles to artistic expression, admitted it had trouble even tracking the scale of the phenomenon. “For the past few years, there have been periods when we haven’t been able to keep up, because the number of cases are multiplying and, above all, they are affecting many more local cultural events,” it warned.

The word “saint” is not appropriate for festival-goers waving a glass of beer in their hand.

No national statistics have been compiled either by the Observatoire de la Liberté de Création or by the Senate. By analysing the local press since 2021, however, Mediapart has come across at least 11 shows and concerts that have been cancelled after threats from far-right Catholic nationalist groups, and a further dozen serious threats made to cultural events from the same sources.

In recent years their focus has been on drag queen performances or readings for children, as well as shows in deconsecrated churches. In June 2021 the singer Eddy de Pretto was forced to perform under police protection at the Saint-Eustache church in Paris’s 1st arrondissement, while a planned concert by singer Bilal Hassani at a deconsecrated church in Metz in north-east France on April 5th 2023 was cancelled, following threats from the far-right groups Aurora Lorraine and Civitas.

Also in April 2023, the Saint-Rock festival in the Saône-et-Loire département or county in central France was threatened simply over its name, which was judged blasphemous by Civitas. “The word ‘saint’ is not appropriate for festival-goers who are waving a glass of beer in their hand, or even under the influence of illicit substances, in front of a so-called music stage,” stated a letter from the local section head of the fundamentalist Catholic organisation, which was subsequently dissolved by the French government later that year.

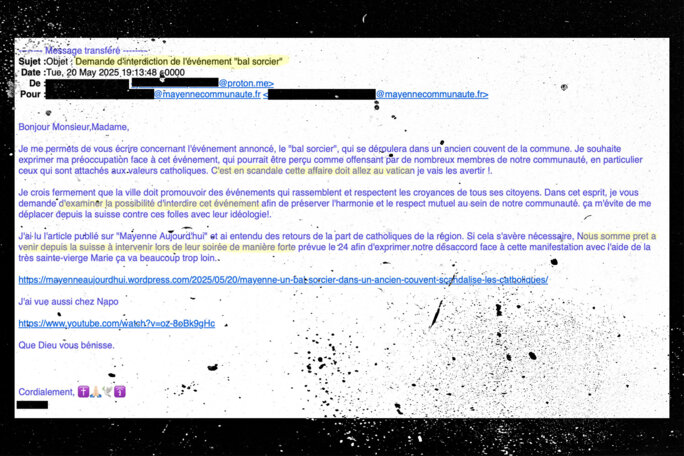

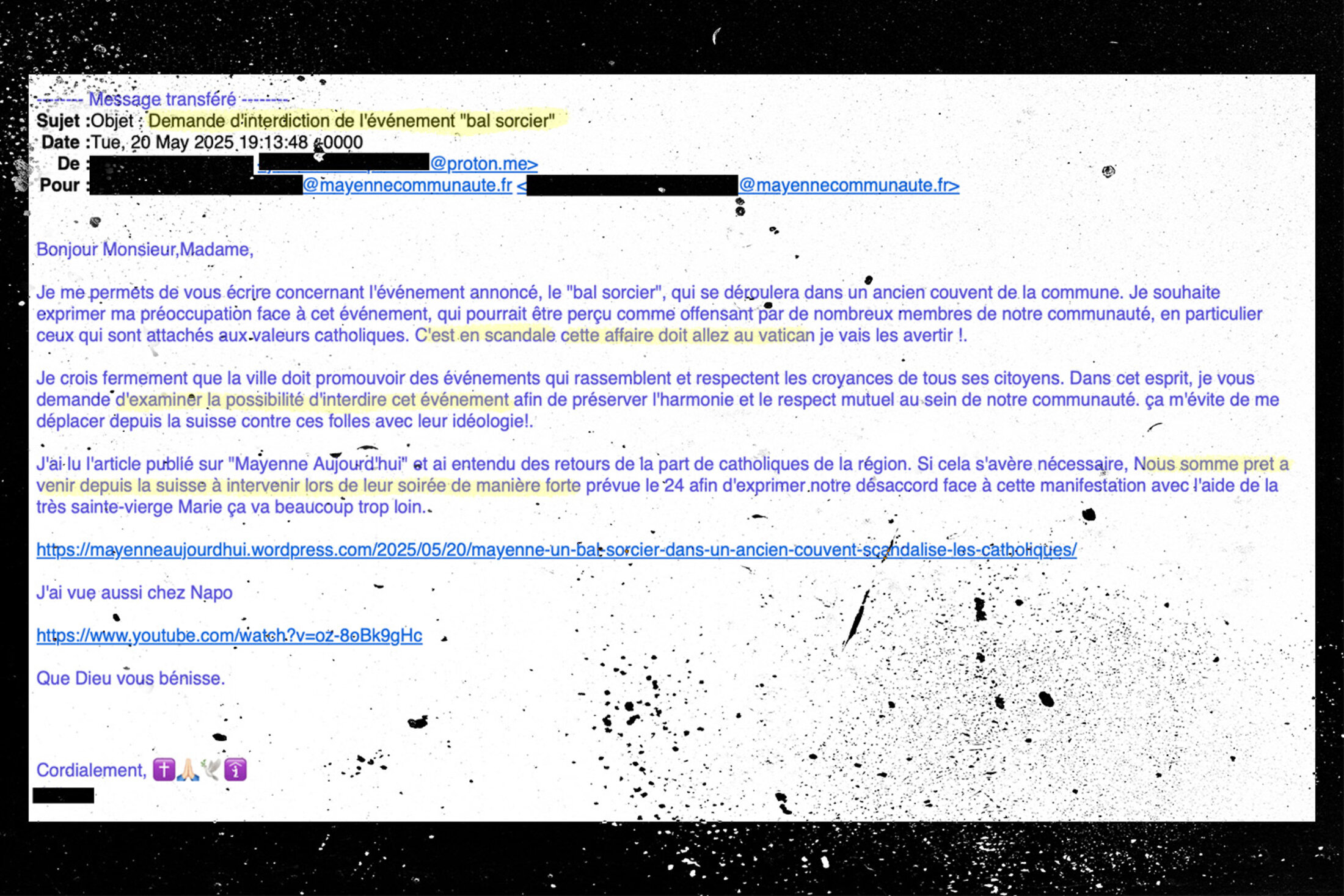

Online onslaught

One of the most recent episodes of intimidation took place in May 2025 at Mayenne in north-western France, a small town of 15,000 inhabitants and a “place of moderates” according to its Socialist mayor Jean-Pierre Le Scornet. Le Bal des Ardentes, a show organised in a deconsecrated convent, aroused the anger of local Catholic nationalists. They called the ball “blasphemy” and urged councillors to scrap it. A Catholic YouTuber described the event as a “witches’ ball”, a “grubby ritual against God” and an “insult to the Catholics of Mayenne”. On his channel, which is followed by some 15,000 people, this influencer called for action to cancel the show. The mayor of Mayenne received a volley of abusive calls and emails, including threats to “come from Switzerland [to] intervene forcefully at their evening”.

Enlargement : Illustration 3

Faced with this online onslaught, the mayor decided to cancel the performance, which had been scheduled for May 24th. “Things really escalated in the two or three days before the show, and my responsibility was to ensure safety,” the mayor told Mediapart. “To get to the site you had to go through a few streets, and I couldn’t count on enough security personnel, since they were tied up with another event,” he added.

The mayor said he had been contacted by the Ministry of Culture and the regional cultural affairs office (DRAC), and had felt well supported by the authorities. Following this cancellation, however, neither the culture minister nor Bruno Retailleau publicly condemned the intimidation, which this time had come from Catholic fundamentalists.

The Journal du dimanche (JDD), a Sunday newspaper owned by French billionaire Vincent Bolloré, which devoted nearly six articles to the Barbie cancellation, was far less hardline when faced with this display of Catholic religious zeal. The Mayenne ball, with its “glitzy demons”, was even described as “inflammatory”. A local councillor for the rightwing Les Républicains party was also quoted in the paper as saying he would prefer to see the convent razed to the ground than host “such irreverent debauchery”. This represents a major about-face for the JDD which a few months later would publish these words: “The Republic means freedom of conscience and cultural freedom. It cannot be bargained away. It cannot bow to intimidation. It must be defended, everywhere, always.”

Huge mass against 'Satanism' in Toulouse

Six months earlier, in Toulouse in the south-west of the country, Catholic fundamentalists opposed a massive street opera by the theatre company La Machine: La Porte des ténèbres. 'Élodie' – not her real name - who works for the city authority there, recalled one of the emails her employer received at the time. She said: “It read: ‘If you don’t stop your blasphemies and scandals, know that you can't mock God, especially when children are shocked […]. Get out of France or you'll be turned to charcoal'.” At the same time, a thousand worshippers gathered for a giant mass to “protect” Toulouse from “dark threats”, a service led led by the archbishop Guy de Kerimel. Threatening leaflets were distributed across the city denouncing the “parade of Lilith the demon-woman, muse of the Hellfest”. An email address 'infos.nonausatanisme@gmail.com' was provided amid calls for people to condemn the event, which ultimately took place without incident.

The mayor of Toulouse, Jean-Luc Moudenc, who is of the Right but with no party affiliation, and whom Mediapart tried unsuccessfully to contact through his office, told Le Figaro newspaper that he “respected the position of Catholics and Protestants”, and that the controversy provided “good publicity for the show”. Two weeks later, the punk festival Setmana Santa, also labelled “satanic” on social media, was unable to stage two concerts in a deconsecrated church. This was after the council withdrew its licence “under the threat of a few crackpots”, in the angry words of the organisers on Facebook.

Censorship spreading wider

These full-on attacks are only the tip of a much larger iceberg, the “ones that work best”, Thomas Perroud, secretary-general of the Observatoire de la Liberté de Création, told Mediapart. He points to “fairly profound changes” in “traditional Catholic censorship”, with a “more subtle” groundswell of opinion. “This summer in Avignon [editor's note, in southern France] we had a lot of meetings, including with the Association des maires de France [editor's note, which represents mayors across the country] and drama teachers.” In those discussions, he says, they spoke about the “activism” of parents’ associations, such as Parents vigilants, a group linked to Éric Zemmour’s far-right Reconquête party.

What's quite worrying is that the Left […], in recent years, has come to embrace censorship and legitimise it.

“What we see with the management in some schools is mobilisation from the grassroots, which the press doesn’t report,” says Thomas Perroud. “But on this or that film or play, parents will mobilise to stop it being shown. And that seriously undermines these shows, which can no longer get school funding.” This type of protest action, led by Civitas, Parents en colère and Parents vigilants, seriously disrupted several performances of the gender-themed show Fille ou garçon, even leading to sabotage and physical threats in Nantes, in western France, in April 2023.

On top of these far-right threats, the Observatoire is also worried about a “diversification as to where demands for censorship come from. Traditionally, it comes from the state or from Catholic or conservative origins,” says Perroud. He has seen a shift since 2014 when the show Exhibit B was condemned by anti-racist activists, and was ultimately staged under police protection at Saint-Denis in the northern suburbs of Paris. “These are censorship demands that also come from groups whose battles we may share – anti-racist, feminist groups,” he noted. “So today we have a spectrum that runs from Right to Left. What's quite worrying is that the Left, which was traditionally more attached to freedom of speech, has in recent years come to embrace censorship and legitimise it.”

The offence of obstruction

His organisation's report also lists the obstacles that are now affecting smaller events, with more frequent actions being taken to “exert pressure that encourages self-censorship among artists and organisers”, which thus weakens the smaller organisations. “Every time there’s a show, I'll ask myself: ‘Am I sure there won’t be a problem?’” admits the mayor of Mayenne, Jean-Pierre Le Scornet. And he considers such an outcome to be “very worrying” and “serious”.

The Senate report also flagged the risk of abandoning the most radical productions, as local councillors “may intervene more or less directly with schedulers, to urge them not to put on works dealing with potentially ‘divisive’ subjects”. Perroud himself says he fears an increase in the number of shows and performances that “don’t shock”, as “that’s not the role of art”. This kind of levelling-down of creative art also comes in a context of brutal austerity, with drastic cuts to cultural funding in several regions.

Faced with these growing hurdles, the Observatoire has called for better awareness among councillors and those operating in the cultural scene.

Since 2016 and the passing of a law on freedom of creation, architecture and heritage – known as LCAP - there has been an offence in France of “obstructing freedom of creation and artistic publication” . However, this is still rarely used because it is too little known and there is little case law. “But above all […], the conditions required to constitute the offence are too strict […], [it] is too conditional,” noted the Observatoire's report to the Senate, which urged a simplification of article 431-1 of the country's Penal Code. The Observatoire's secretary-general nevertheless welcomed the creation of a dedicated senior civil servant post at the culture ministry, as part of a Plan pour la liberté de création ('creative freedom framework') rolled out in December 2024 by culture minister Rachida Dati.

In the meantime, Noisy-le-Sec town hall will show Barbie in early September, coupled with a debate. The deputy mayor in charge of culture, Wiam Berhouma, told Mediapart that the original cancellation was “not at all representative of the reality on the ground”, where threats “most often come from rightwing or far-right opponents, or even institutions”.

In Mayenne, mayor Jean-Pierre Le Scornet also intends to reschedule his Bal des Ardentes, with one new concern: “While six months ago I’d never have asked myself this question, if we do put it on again, I'll make sure we have sufficient security services so the show can go ahead without a hitch.”

--------------------------------------------------------------------------

- The original French version of this article can be found here.

English version by Michael Streeter