One of the stands at the Red Star Football Club at Saint-Ouen in the northern suburbs of Paris bears the name of Rino Della Negra. And during matches at this legendary club – the fourth oldest in France and whose heyday was in the inter-war years – there are regularly songs and banners in 'Rino's' honour.

This young footballer played on the right wing for Red Star during the 1943-1944 season. At the time he joined the club, aged 20, Rino Della Negra had already been active in the French Resistance for several months. Indeed, he was a member of the renowned Resistance group known as the FTP-MOPI – made up of immigrant workers – led by the Franco-Armenian poet and communist Missak Manouchian.

Rino Della Negra was shot by the Nazis on February 21st 1944 at Fort Mont-Valérien in the western suburbs of the French capital. But he was to live on in the memory of activists on the far-left and then among Red Star fans themselves. Now historians Dimitri Manessis and Jean Vigreux - the latter is professor contemporary history at the university of Bourgogne-Franche-Comté in eastern France - have just written Rino Della Negra, footballeur et partisan, published by Libertalia in February. This groundbreaking book sheds light on the story of a working class son of Italian immigrants from Argenteuil in the north-west suburbs of Paris, one in which working class solidarity, a passion for football and the fight against fascism are interwoven. This biography also challenges the outmoded idea of “national identity” that is popular today on the far-right; the young Resistance fighter's story took place in a France that was both multicultural and a place of welcome for refugees. Mediapart met the authors.

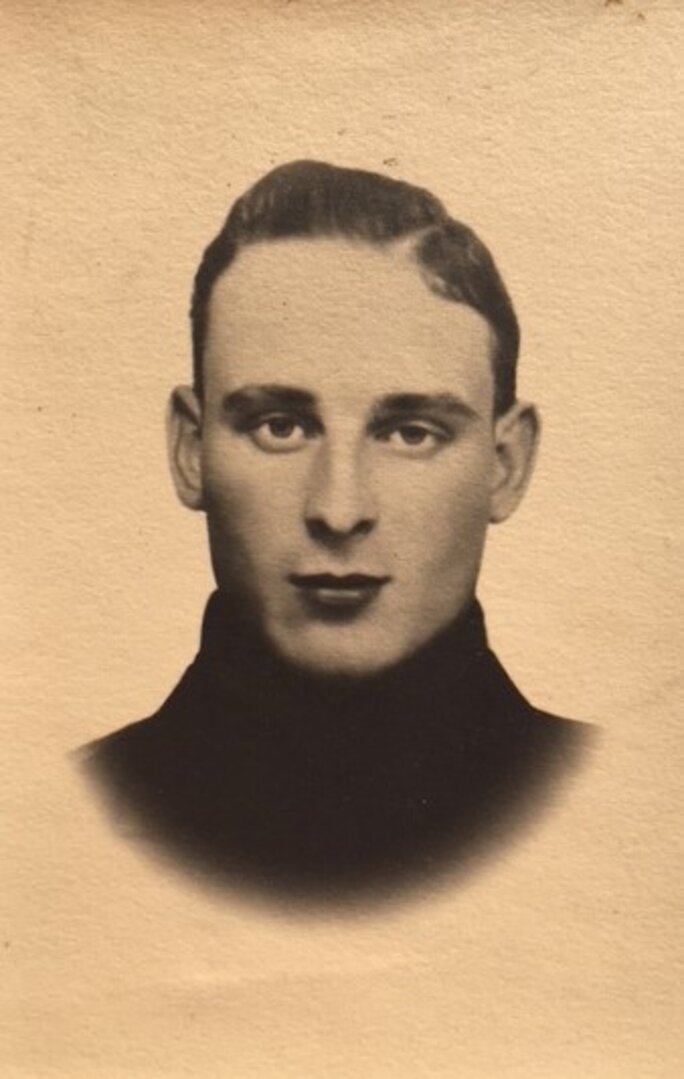

Enlargement : Illustration 1

Mediapart: Reading this biography of Rino Della Negra, one is struck in the opening pages how it was his neighbourhood in Argenteuil which forged his political outlook.

Dimitri Manessis: Rino Della Negra arrived in Argenteuil in 1926 at the age of three, having been born in the Pas-de-Calais [editor's note, in northern France]. His Italian parents were originally from Friuli [in north-east France] and moved because his father, a brickmaker, got work on building sites here.

Della Negra lived in the Mazagran neighbourhood which was nicknamed 'Mazzagrande' because lots of Italian immigrants lived there. This 'Little Italy' was to help nurture the young Rino Della Negra's politics, in particular the different places where the working classes met and socialised, such as the café Chez Mario, with its boules court and its card games, activities that were specific to working class culture at the time.

Della Negra was a melting pot of working class and Italian cultures, based as much around anti-fascism as around food. For on top of the social side there was a network of Italians friends who had fled the Mussolini regime and who had come to France with the aim of carrying on the struggle.

We don't know the Della Negra family's political affiliations but as a youngster Rino was close to the Simonazzi family, who were known for their involvement in the anti-fascism struggle and the Italian Communist Party (PCI) in exile.

To give an example, one of the Simonazzi brothers, Tonino, who played football with Rino for the Jeunesse Sportive Argenteuillaise (JSA) club, went to fight with the International Brigades in Spain [editor's note, during the Spanish Civil War] with another youth from Argenteuil, André Crouin. These friends of Rino Della Negra came back from this conflict wounded and one can only imagine the political and emotional impression that the two young fighters from Spain made on this young adolescent of Italian origins.

Jean Vigreux: Argenteuil was in what was called at the time the “red suburb”. [Journalist, politician and later Resistance fighter] Gabriel Péri had been the communist Member of Parliament for the constituency since 1932 and control of the town hall was won by the [communist] party in 1935.

Rino Della Negra entered the world of work at the age of 14 when he was hired as a fitter at the Chausson metalworking factory at Asnières, in the north-west suburbs of Paris, which specialised in making vehicle radiators. His social awareness developed in the workplace during a period when the Front Populaire [editor's note, the union of various parties and groups on the Left that came to power in in France 1936] was in power, and at a time in which the factory experienced both strikes and the repression of union leaders.

Mediapart: Sport and politics also went hand-in-hand during this inter-war period...

Jean Vigreux: This was right at the time when working class education was being promoted by the FSGT (the Fédération Sportive et Gymnique du Travail), the all-sport red federation. Rino Della Negra was an accomplished sportsperson: through the FSGT he played football and did athletics and he can be seen in photos as a boxer, and also with young sportspeople of his age, as part of the practice of mixing up different activities and non-specialisation in sport adopted by the FSGT. He was also a member of the Chausson factory's works team, and thus part of the long tradition of working class football.

Dimitri Manessis: His first club as a footballer was FC Argenteuillais in 1937, but more significantly he joined the JSA, which was affiliated to the FSGT, where he played with the Simonazzis and members of the Armenian community. It was an internationalist football club, which among other things showed solidarity with the Spanish Republicans.

He was later spotted by one of the leading and most prestigious clubs of the era, Red Star from Saint-Ouen, where he signed to play on the right wing for the 1943-1944 season.

What is extraordinary is that by the time Rino Della Negra started his high-level football career at Red Star, he had already dodged the Service du travail obligatoire (STO) [editor's note, the organised system of deportation of French workers to work camps in German] and was an active member of the Resistance army under a false identity!

Mediapart: How did he move from being a worker and footballer to a partisan?

Jean Vigreux: It's hard to say. Rino Della Negra was probably recruited via sporting networks by football players who had become leaders in the Francs-tireurs et Partisans (FTP, the French communist resistance army) or by his Armenian friends.

He was initially involved in the FTP in Argenteuil, a very active group that was led by an Italian man called Floravanti Terzi, known as 'Avanti'. He then quickly moved to the FTP-MOI (Francs-tireurs et partisans-Main-d’œuvre immigrée) [editor's note, a section for immigrant workers] in its 3rd Italian detachment, under the codename 'Robin'.

Dimitri Manessi: The question remains open: the sporting and cultural worlds in which Della Negra was immersed must have played a role in his recruitment to the armed struggle.

We should also highlight the important role of women in Rino Della Negra's involvement, for example Inès Sacchetti-Tonsi, who was his courier. She was a part of the 'Mazzagrande' community [editor's note, in Argenteuil] and her father had been wounded by a Blackshirts bullet [editor's note, the Italian fascist group].

In June 1943 he was a member of the group which attacked the headquarters of the Italian Fascist Party in Paris, and then the unit which shot and wounded the Nazi general Von Apt in the 16th arrondissement.

Jean Vigreux: At the time Rino Della Negra was only 20 years old and he was the youngest in his FTP-MOI detachment. His involvement was very swift, as having dodged the STO in February 1943 he took part in his first Resistance action in June 1943. Within the partisan group he was involved in the actual attacks as well as being the lookout or the person helping others escape once the operation was over.

Mediapart: The level of his involvement in the armed attacks is striking. Until his arrest in November 1943 Rino Della Negra took part in around 15 Resistance operations in six months, while at the same time playing at a major football club.

Dimitri Manessis: Life for the partisans in the Paris region was intense. They fought with weapons in their hands in a very 'proactive' way.

Della Negra took part in a series of attacks and sabotage attempts against collaborators as well as the Germans. In June 1943 he was a member of the group which attacked the headquarters of the Italian fascist part in Paris, then the group which shot and wounded the Nazi general Von Apt in Paris's 16th arrondissement [editor's note, district]. He also headed a team that led an operation against German soldiers at the Guynemer barracks at Rueil-Malmaison [editor's note, in west Paris].

Jean Vigreux: The armed Resistance had a military dimension but also a political one. The FTP-MOI were carrying on the fight of their fathers in Italy, of their older friends in Spain, with one common denominator: anti-fascism.

During this time of clandestine activity, Rino Della Negra played for Red Star under his real identity, he had such nerve! It was so blatant that he wasn't even identified and followed by the Special Brigades – a collaborationist police who specialised in tracking down, among others, communists and those who dodged the STO. He played eight matches between his recruitment by Red Star at the start of the 1943-1944 season and his arrest in November 1943.

Dimitri Manessis: On November 12th 1943 Della Negra took part in an operation against a German convoy carrying cash in rue Lafayette in Paris's 9th arrondissement which went wrong. He was wounded in the lower back and arrested and then taken to the Pitié-Salpêtrière hospital. He was questioned by French police and then by the Gestapo. Torture was routinely used at that time.

He was later tried by a German court martial along with 22 other members of the FTP-MOI in February 1944, in what was known as the trial of the 'Manouchian Group'. This gave rise to the well-known 'Affiche Rouge' ('Red Poster') of which the Germans plastered 15,000 copies on walls across France [editor's note, it featured ten of the 'Manouchian Group' and was intended to portray them as foreign criminals rather than patriots, though this ploy backfired and the poster is said to have inspired others to action].

Rino Della Negra did not feature on this poster. The contradictory theories are that either he had been too badly beaten by the police or, on the contrary, that he had had talked, which does not correspond with the wishful thinking of Nazi propaganda at the time: that it was stateless people and Jews who, manipulated by Moscow, were carrying out terrorist acts.

Mediapart: During the trial of the Manouchian Group the French press reported that Rino Della Negra was just a young footballer unaware of his actions...

Jean Vigreux: The FTP-MOI members were under instructions to play down the number of actions they were involved in during police interrogation, to protect the group.

You can see this in the reports from the Special Brigades: how he was apparently just a footballer who by chance fell into terrorism. But in the trial verdict, 'K' for communist was written next to Rino Della Negra's name.

Dimitri Manessis: The propaganda of the period insisted that those in the Resistance were “Judeo-Bolsheviks” or young people manipulated by them. Rino supposedly dodged the STO simply out of love of football. The collaborationist judges and press denied any political awareness on his part and sought to depoliticise his actions.

But the farewell letters that he sent to his family before he was shot at Fort Mont-Valérien on February 21st 1944 - along with other members of the Manouchian Group - show the opposite. He fully acknowledged his political commitment, asking his family to look upon him as a soldier who died at the front.

Jean Vigreux: A 20-year-old's zest for life runs through his letters, his family, political and sporting social side. His mates at Red Star and his partying – he invites his friends to have a big feast and “get plastered” while thinking of him - also feature there.

But one also senses, and it's very emotional, his self-sacrifice. His parents were not aware of his involvement in the armed struggle and in essence he tells them: “I had to do it.”

Mediapart: How did the memory of his commitment endure after the war?

Dimitri Manessis: It was initially the communist world that kept the story of Rino Della Negra going. Sporting and humanitarian associations, those of former Resistance members and also immigrants connected to the cultural network of the French Communist Party passed down the memory of Della Negra's combat.

At the beginning of the 1950s, at a time of Cold War anti-communism and xenophobia, the story of the FTP-MOI groups was highlighted once more, even as former immigrant members of the Resistance, in particular Spaniards and Poles, were being expelled from French soil. Rino Della Negra's story was used by the Communist Party to show that immigrants had fought for France.

Rino Della Negra encapsulated the values that supporters identified with: anti-racism, anti-fascism, defence of immigrants, the Resistance's social manifesto, internationalism …

Jean Vigreux: In 1966 the municipal council in Argenteuil named a street 'rue Rino Della Negra' and some halls in the neighbourhood were given his name. Other communist groups, such as the Trotskyists, and the Maoists from Argenteuil, who had called their cell 'Rino Della Negra', also staked a claim to the footballing partisan's legacy.

Mediapart: Today Rino Della Negra is an icon of grassroots football, in particular among supporters of Red Star at Saint-Ouen. When did his name return to the stadium's stands?

Dimitri Manessis: In September 1944 the FSGT organised a Rino Della Negra Cup. And the following year this trophy was won by Red Star, who handed over the trophy to the Resistance member's parents. But this sporting memory faded over the years, before being revived thanks to the efforts of Claude Dewael, a specialist in the history of Saint-Ouen, who wrote about the player in December 2000.

It was then that the Red Star supporters rediscovered this Resistance figure, and the reason this book exists today is down to the club's fans reviving his memory.

Jean Vigreux: In 2002 Jean-Marie Le Pen [editor's note, then head of the far-right Front National party] made it through to the second round of the French presidential election and, in the eyes of many supporters, Rino Della Negra encapsulated the values that they identified with: anti-racism, anti-fascism, defence of immigrants, the Resistance's social manifesto, internationalism...

Enlargement : Illustration 3

In 2004 a commemorative plaque was put up at the entrance to the Red Star stadium in the presence of fans, the Della Negra family, local authorities and senior figures at the club. To mark the occasion a match was organised between Red Star and an Armenian team from Issy-les-Moulineaux in the south-west suburbs of Paris.

Each February 21st club supporters commemorate his execution by the Nazis at Fort Mont-Valérien. Songs, banners, scarves and visual displays in the stand, which is named 'Rino Della Negra', regularly recall the young martyr's fight against fascism.

Mediapart: At the end of your work you underline the extent to which his story challenges the nebulous concept of “national identity”...

Dimitri Manessis: Rino Della Negra in fact represents a pluralist France. His is a story of anti-fascist commitment on the part of a young man of immigrant origins, from the working classes, and who lived in the suburbs.

We re-examine the notion of patriotism at that time, an idea that is today associated with a rancid vision of national identity, when for the FTP [Resistance groups] this concept was linked to internationalism, the 1789 Revolution, to a Republican social model that included immigrants, men and women.

Jean Vigreux: We wanted to produce a social history of this commitment to the Resistance, one which is part of another national narrative: that of a France as a place of welcome for Italian anti-fascists as it was also for Jews persecuted in Central Europe.

At a time of sickening speeches about migrants, Rino Della Negra's life story is part of current events and, more broadly, the history of all those who have been downtrodden.

---------------------------------------------------------------------------

- The original French version of this article can be found here.

English version by Michael Streeter