For five days after the massive blaze which swept through the Lubrizol chemical plant at Rouen in northern France, key questions remained unanswered. Which products burned in the fire on Thursday 26th September? What substances were released into the air? It was only on the afternoon of Tuesday October 1st that the local prefecture released details of the 5,253 tonnes of chemicals that were involved in the incident.

On that same day many different organisations had held a demonstration calling for the “truth about the fire”. The day before there had been a tense gathering of around 500 people, including farmers, teachers, parents and firefighters, expressing their concerns and fears. The absence of a clear response to simple and basic questions from the residents of Rouen and the surrounding area had fuelled a palpable sense of unease, and in some cases a form of panic.

The management of the chemical firm Lubrizol has deposed a formal complaint against persons unknown for “involuntary destruction by explosion or fire”. It also stated that “video surveillance” and “eye witnesses” could indicate that the fire in fact started “outside” the plant site. It is still not known where the fire started and where it initially spread. A judicial investigation is underway and some people have already been interviewed by the police.

Despite the delay in publishing it, the list of dangerous products at the plant was not in fact a secret. They feature in the 2016 reports made by the inspectorate in charge of moitoring potentially hazardous sites, the Inspection des Installations Classées, which Mediapart has seen. The reports mention in particular zinc dialkyldithiophosphates and derived products which are used as anti-wear additives in lubricants and which are particularly toxic.

Enlargement : Illustration 1

The raw materials and products stored and made on the Lubrizol site at Rouen are oils, solvents, anti-corrosives, antioxidants and hydrocarbon polymers. “Some products, such as antioxidants, are dangerous for the environment and noxious,” said the inspector in one report. In 2016, when the report was written, the “risk of release of toxic fumes” from antioxidants “outside the site has not been considered by the operator”.

Some of the products in the factory, used either in oils or to treat water, are “irritants, noxious, toxic, easily flammable or dangerous for the environment” writes the inspector. Diesel, compressed air, liquid nitrogen, steam and natural gas are also kept on the site and could represent an additional danger, the reports say.

Most of these substances can catch fire when the temperature is above 55 °C. “If there is a fire, certain products could give rise to the creation of toxic substances, the risk of the release of toxic fumes outside the site has been considered by the operator according to the nature of the product affected,” says the 2016 report. That was why it was so important to know both the nature and quantity of the chemicals affected by the fire last week.

The Lubrizol factory produces additives for lubricants. It is classified as 'high level' under the Seveso classification for hazardous sites, the highest risk level in France. This is for two reasons. One is that it makes and stores products that are toxic or very toxic for aquatic organisms, and the other is the presence of substances and mixtures which release toxic gases on contact with water. The site contains production tanks, production lines, oil supply lines, steam pipes and storage areas.

The factory's operator recorded twelve accidents since 2004 involving the equipment that was examined by the inspectorate in 2016, of which eight concerned spillages (for example when a container was knocked over), one a release of hydrogen sulphide, and another a release of hydrochloric acid. A unit that makes additives for oils – called the SBR unit – had had four accidents including a fire since 2004. On September 29th 2015 an oil tank overflowed “leading to pollution of the public urban rainwater drainage network”.

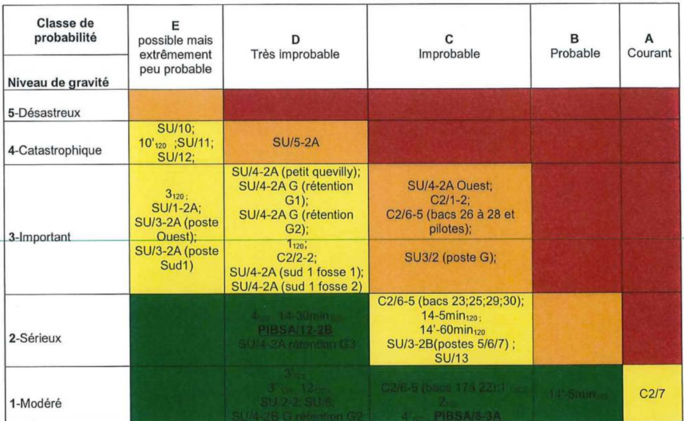

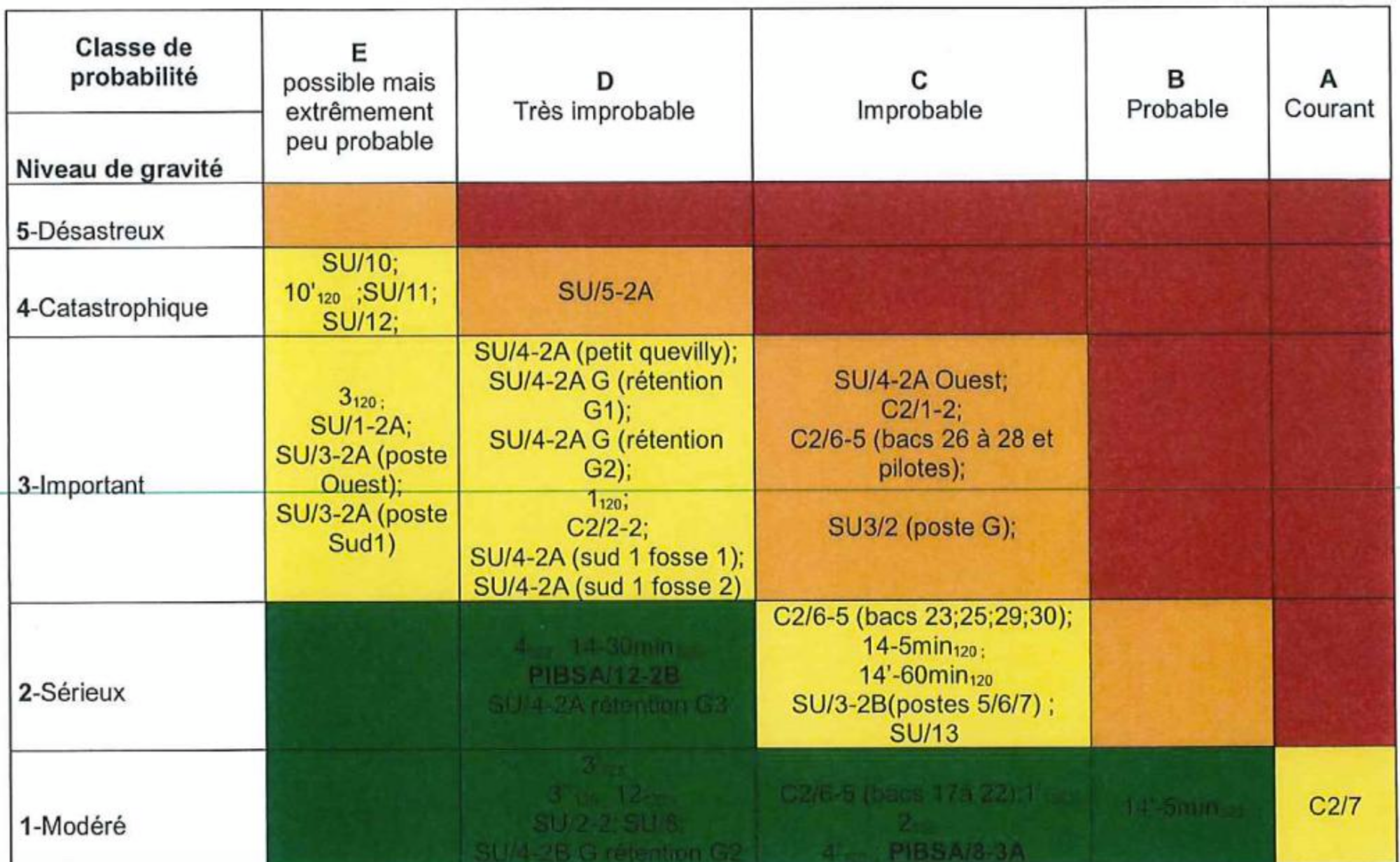

The 2016 reports from the inspection team also show the factory's table of “risk control measures”. This document is flagged up as “not publishable” because of its sensitive nature. It categorises the risks of accidents in various locations according to their seriousness (from “moderate” to “disastrous”). Different facilities in the plant are identified as potentially at risk: the C2 workshop and the facility producing PIBSA or polyisobutylene succinic anhydride-based emulsifiers.

Officials also labelled a specific study on the C2 workshop to highlight any dangerous phenomena as “not publishable”. This facility makes additives using 16 mixers. “There are many products present,” write the inspectors. “They involve organic materials used in the making of detergents, antioxidants, anti-wear [products], anti-foaming [products], dispersants or in modifying the viscosity of oils.”

Some products are “irritants, dangerous for the environment, toxic (for example the anti-foaming [products]), noxious,” says the March 2016 report. “The sulphur content of some products can be particularly high (for example 20%),” it notes. In the event of a fire “the products would give rise to the creation of toxic substances generated by the oxidation of phosphorous, sulphide, nitrogen molecules with the risk of leading to toxic gas (SO2, Nox) in the fumes”.

Finally “in the event of decomposition a section of the products could potentially generate an emission of hydrogen sulphide”, a report notes. In 2016 Lubrizol recorded a total of 30 incidents and accidents in the plant's mixing unit since 2004, including two outbreaks of fire and the heating up of equipment.

At the time six potential accident scenarios that could result in a fire were reviewed. These included equipment not being contained inside the workshop, issues at the lorry unloading bay at the storage facility on the west of the site, problems with the anti-foaming equipment and so on.

In November 2010 a decree by the state prefecture ordered Lubrizol to build a firewall at a specific location. It had still not been built by 2016. Neither the prefecture nor Lubrizol had responded to questions on whether it has since been built by the time this article was published.

Public authorities 'lax' with the factory

It is as this stage impossible to know if the C2 workshop played a particular role in the Lubrizol factory fire. But what is clear is that it was given a special administrative favour concerning a dangerous product.

In 2019 the prefecture in the local département or county of Seine-Maritime authorised Lubrizol to increase its storage capacity for unspecified “very inflammable” products by 1,598 tonnes, as reported by the environmental website Actu Environnement. Yet there is a mandatory and specific procedure to go through when any such increase exceeds a thousand tonnes. That did not take place in this case. There was no risk or impact study carried out.

In the 2016 reports the inspector's assessments of the facilities are generally favourable to the operator. On several occasions the author writes that “the principal risks highlighted in the internal and external accidentology [editor's note, the study of accidents] at the site have been taken into account by the company Lubrizol in its analysis of the risks”. And that “the methodology used by the operator for the carrying out of its preliminary evaluation of the risks is judged to be acceptable”.

Enlargement : Illustration 2

But the inspector also makes several requests for risk control to be bolstered: in particular ensuring the continued surveillance of the emission of several substances – nonylphenols, zinc and the organic compounds Di-2-ethylhexyl phthalate – into the River Seine.

The inspector says that in relation to these first two products measurements had shown that a threshold had been passed and that concentrations ten times the normal environmental level had been recorded. The official also wanted to add new instructions concerning the risk assessment of facilities producing 20,000 tonnes of anhydride polyolefins and 25,000 tonnes of hydrocarbon dispersants (PIBSAs) a year.

Other control risk measures were announced for the future: a security mechanism for high temperatures linked to a visual and sound alarm, as well as a hydrogen sulphide (H2S) gas detector. These new measures also include an automatic fire detection system with manual controls at the storage unloading bay (to the west of the factory), barriers to prevent the risk of tanks overflowing, and transfers pumps fitted with level monitoring alarms in the oil storage tanks. Yet another planned move was implementing measures that would allow any water discharged in putting out a fire in a particular building, building G, to be contained.

The prefecture did not respond to Mediapart's questions on whether these measures have been implemented. Nor did the company's communications department in the United States where the company is based.

Though on Tuesday evening the prefecture did finally release details of the chemicals and quantities involved in the fire, that came five days after the blaze itself. In the meantime many local residents have not received answers to their questions. Environmental groups seeking greater openness from industrial groups think that this is because since 2017 a regulation has restricted the publication of sensitive information about what substances are present in such factories.

This came after the terrorist attacks in Paris and neighbouring Saint-Denis in 2015, and resulting demands that less information should be given out, to avoid possible attacks on chemical plants.

“In the past all this information was accessible,” explains Claude Barbay, who is a member of the site-monitoring committee or CSS for the environmental group France Nature Environnement (FNE). “They suddenly closed everything in 2017 following the appearance of a wretched circular on 'opaque' transparency. We went back to the situation of non-information which existed before the AZF accident at Toulouse in 2001 [editor's note, an explosion at a chemical plant on September 21st 2001 which killed 29 people and left 2,500 injured]. We can't blame local manufacturers for it.”

Barbay is today calling for a special site-monitoring committee to look into the causes and consequences of the Rouen fire. But he is dismayed at the “paternalistic, inward-looking” mindset at Lubrizol, where the only active trade union is an in-house organisation. He is also unhappy with the defensive, closed ranks approach of the company which he says “always has the impression that we are looking to harm it” when it is asked questions.

Guillaume Blavette, who is a member of a departmental consultative committee the Conseil de l’Environnement et des Risques Sanitaires et Technologiques (CODERST) for France Nature Environnement, is also unhappy at the lack of information given to local residents. “You can't have any debate in CODERST, you can't ask questions, the operators are not summoned, you can't do anything,” he says.

The consequence of this, he says, is that in the end the protection of public health and the environment “depends as much on the goodwill of the operators as on the state”. He sees this as one of the main reasons why local people mistrust the state on the issue. “It all stems from the lack of sincerity in public messages. If you set up a genuine dialogue with the residents there is less mistrust if there is an accident,” he says.

The Lubrizol factory at Rouen has been treated in a special way because of the dangerous nature of the products there. Since 2014 it has had a specific risk prevention plan or Plan de Prévention des Risques Technologiques (PPRT). But it has not renewed its risk analysis.

This document, which is crucial for analysing the potential risks at an industrial site, goes back to 2009. In line with industrial sites with a high classification on the Seveso scale of hazardous risks, this document should have been reviewed in 2014 and then again five years later. But as far as Mediapart this review had still not taken place by the end of September 2019. So one of the many questions that remain to be answered is why the public authorities have been so lax with this company.

-------------------------

If you have information of public interest you would like to pass on to Mediapart for investigation you can contact us at this email address: enquete@mediapart.fr. If you wish to send us documents for our scrutiny via our highly secure platform please go to https://www.frenchleaks.fr/ which is presented in both English and French.

-------------------------

- The French version of this article can be found here.

English version by Michael Streeter