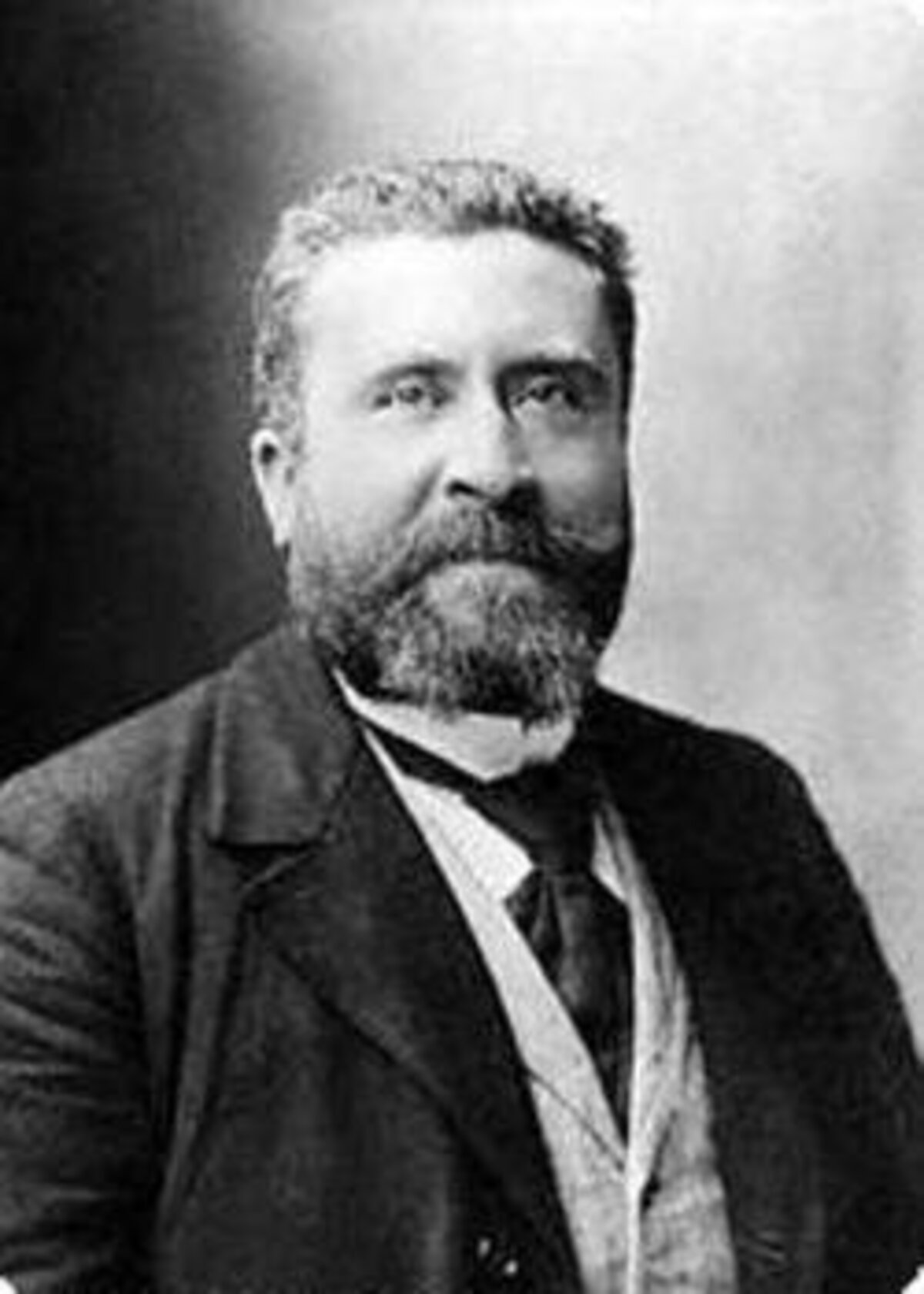

Jean Jaurès (1859-1914) is arguably the most revered of any left-wing politician in France, remembered as one of the country’s greatest orators, and a passionate and tireless campaigner against injustice.

The once moderate republican who became a grand socialist leader is as much a presence in the minds and speeches of policy-makers of the Left as he is on the name plaques of streets, squares, schools, libraries and other public buildings around France.

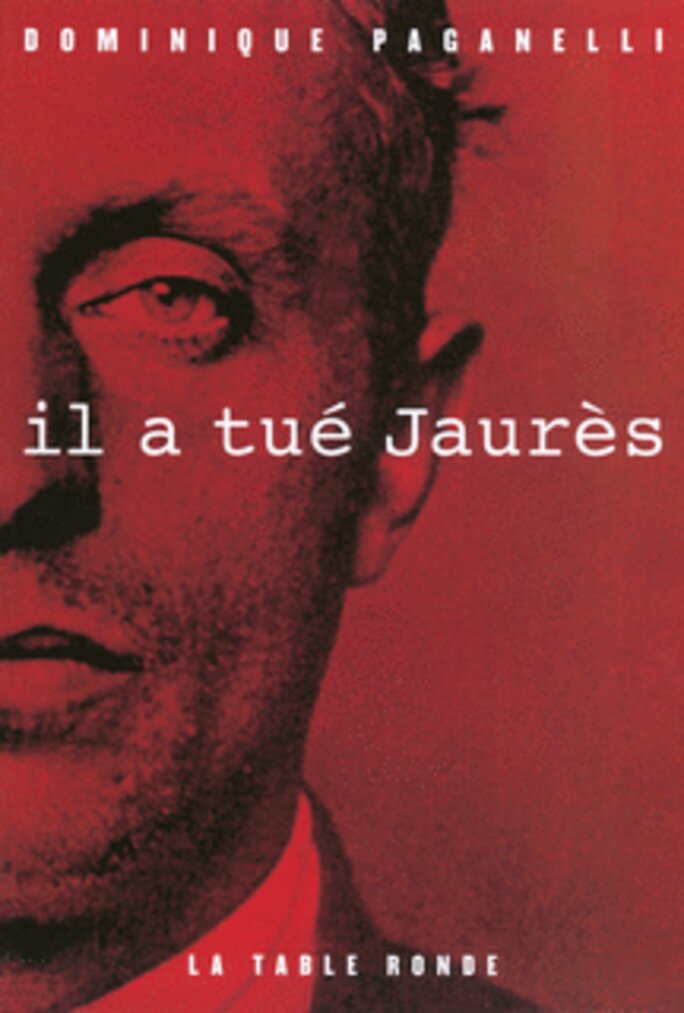

Among the several books published this year marking the 100th anniversary of his assassination, one focuses upon the largely ignored and extraordinary outcome of the trial of his killer, acquitted by a jury despite assuming full responsibility for his act, which he carried out alone and in front of numerous witnesses. The story of the trial, held shortly after the end of World War One (WWI), is also that of the political and social atmosphere prevalent in France after the 1918 armistice.

Jaurès, who began his career as a schoolteacher after brilliant studies at the École Normale Supérieure in Paris, became a republican Member of Parliament (MP) in 1885 at the age of just 26, when he was elected in a constituency in the Tarn département (county) of south-west France.

His political conversion came during a bitter three-year miners’ strike, between 1892 and 1895, in his constituency town of Carmaux, where he was subsequently re-elected in 1893 as a socialist MP. He lost the seat five years later, but won it back again in 1902, the year he became leader of the French Socialist Party - and would keep it until his death.

Jaurès, who never held a government post, gained national recognition for his untiring attacks against injustices, and played a key role in defending (although not at first) French army captain Alfred Dreyfuss after the latter was framed and wrongly accused of treason in the infamous case that became known as The Dreyfuss Affair.

The founder of L’Humanité, a self-proclaimed “socialist daily” which he edited until his assassination, Jaurès was a passionate antimilitarist who, during the final years of his life, campaigned tirelessly to prevent the approaching war in Europe.

On July 31st 1914, during the final countdown to WWI, Jaurès, who was then 54 years-old, spent the day once more attempting to lead France away from the conflict, first in parliament and later in a meeting at the French foreign affairs ministry. At the time, the socialist Second International organisation, which his party (the French Section of the Worker’s International, or SFIO) was a part of, had announced the call for a general strike in France and Germany if war was declared.

During the evening of that last day in July, he returned to his office at L’Humanité, close to the bustling ‘Grands Boulevards’ in the 2nd arrondissement of Paris, the district that was home to most of the French national press. He and his journalist colleagues dined at the nearby Café du Croissant, on the rue Montmartre, where Raoul Villain, a deranged 29 year-old member of a nationalist movement, shot Jaurès dead through one of the café’s open windows.

Villain was arrested and jailed, but his trial was delayed until the end of the war, and opened in March 1919, five months after the armistice. Villain, who had shot Jaurès in front of several witnesses, claimed full responsibility for his act, and yet a jury of 12 members of the public acquitted him. In a book published last month, Il a tué Jaurès (‘He Killed Jaurès’), journalist Dominique Paganelli details the trial and the police investigation, using numerous archived documents from the time

“There was an atmosphere of victory, of nationalism, of Germanophobia to the extent that the jury represents this taste of victory and was resentful of those who, before, sought peace and might have prevented this victory over the Germans,” said Paganelli in a recent interview with France Inter radio. “Villain’s lawyers played on that theme. The lawyers for the civil party, Madame Jaurès, did not understand this situation. They spoke of a wonderful Jaurès, a demi-god. The jury couldn’t care less. They didn’t want that Jaurès, because he would have deprived them of the victory that they [then] enjoyed.”

Paganelli dug up a newspaper article in which a member of the jury revealed their secret discussions, and who admitted to making a political decision by acquitting Villain despite being fully convinced that he murdered Jaurès. “In short," Paganelli said, “they justify his act and they say ‘you were right, Raoul Villain, to have killed Jaurès’”.

The trial became that of pacifism and the supposed defeatism that, in the eyes of the hate-mongering and bellicose far-right, Jaurès represented. The public prosecutor asked for “a reduced sentence” which he argued would “appease” opinion, while the civil parties, made up of Jaurès’ family, were absent during the course of the trial. To observers, it appeared likely that Villain would be found guilty but that mitigating circumstances would be recognised, allowing for a prison sentence of at least the four-and-a-half years he had already spent in prison.

Villain’s lawyers argued that his act was a momentary moment of madness, a crime of passion by a sincere patriot, and they called for a verdict of reconciliation and appeasement after the long years of war. The unthinkable followed: not only was Villain acquitted, but Jaurès’ widow, Louise, was ordered to pay legal costs as stipulated by law at the time which decreed whichever party loses its case at trial “will be ordered to [pay] costs to the state and the other party”.

In the same courthouse two weeks earlier, on March 14th 1919, a 22 year-old anarchist was tried for the attempted murder, one month earlier, of French Prime Minister Georges Clemenceau. From close range, Emile Cottin fired several shots at 78 year-old Clemenceau, who escaped serious wounds but who lived the following final ten years of his life with a bullet lodged close to his heart. Cottin was shown no clemency and was sentenced to death for his act, although Clemenceau himself later commuted the sentence to ten years in prison.

In a remarkable coincidence of fate, both Cottin and Villain were to later be killed, in quite different circumstances and within a month of each other, during the Spanish Civil War.

During his trial, Villain’s lawyers evoked the dramatic and politically highly-charged context of 1914 - and the case of Henriette Caillaux, wife of French finance minister Joseph Caillaux. In March 1914, she shot and killed Gaston Calmette, the editorial director of French daily Le Figaro, for having published a document that was severely damaging to her husband’s reputation. It was just three days before the assassination of Jaurès that the trial of Henriette Caillaux ended with her acquittal on the grounds of a crime of passion.

As for the lawyers representing Louise Jaurès, their addresses to the court were subdued by concern for the political rehabilitation of Jean Jaurès and his socialist party, the French Section of the Workers’ International (SFIO) – which would split into two 18 months later at the Tours Congress and which was eventually replaced in 1969 by today’s Socialist Party. They demanded a sentence of principle against Villain, and one that above all should not be execution, which Jaurès himself had long campaigned against.

In a passionate speech before the French parliament on November 18th 1908, Jaurès denounced the hypocrisy of the death penalty. “Ah! It’s an easy thing, a convenient process,” he told the chamber. “A crime is committed, one brings a man to mount the scaffold, a head falls. The question is settled, the problem resolved. We say it is simply asked. We say that our duty is to smash the guillotine and to look, beyond, to the social responsibilities."

"Well! With what right does a society, which through egoism, through inertia, through connivance with the easy delight of a few, has not halted any of the sources of crime that it was charged with halting," asked Jaurès, "neither alcoholism, neither vagrancy, neither unemployment nor prostitution - with what right does this society then come back to strike, in the case of a few miserable individuals, the very crime for which it has not looked at the origins?”

As for Villain, he later settled on the Spanish island of Ibiza, where he built a house in the bay of Cala de San Vicent. In September 1936, after the outbreak of the Spanish Civil War, a group of Republican soldiers, reportedly anarchists, landed on a beach close to his home as part of a larger force to re-take the island from the Nationalists of General Franco. In circumstances that remain unclear, Villain, who the soldiers were suspicious of and kept under guard, was shot in the back and died after agonizing for 48 hours.

The following month, Emile Cottin, who shot Clemenceau in February 1919, was killed in battle on the Aragón front, near Pina de Ebro, in the province of Zaragoza, while fighting for the Republican side with the anarchist Durutti Column.

-------------------------

- Dominique Paganelli's book 'Il a tué Jean Jaurès' is published in France by Les Editions de La Table Ronde, priced 16 euros.

-------------------------

- The French version of this article can be found here.

English version by Graham Tearse