A French administrative court has just approved the building of a new motorway junction close to schools attended by 700 pupils and in a working class town of Saint-Denis north of Paris which is already heavily congested and polluted. The work, part of the preparations for the Olympic Games being staged in Paris in 2024, involves building two additional entry and exit slip roads off the A 86 motorway close to the major Pleyel crossroads by 2023.

Yet a recent study by UNICEF of Paris and the surrounding area showed once again that children are the biggest victims of vehicular pollution because of their growing bodies and their prolonged exposure to it. Which raises the question: why is a new junction being built so close to where pupils are being taught?

The Pleyel district of Saint-Denis in the Seine-Saint-Denis département or county north of Paris is a mixed neighbourhood with a combination of offices, a huge dilapidated tower block, brand-new student accommodation, old brick-built blocks of flats, new flats being built with a view of the Sacré-Cœur basilica in northern central Paris, betting shops, social housing and old workers' cottages. Thousands of vehicles hurtle through the area each day, heading to or from the centre of Paris.

Enlargement : Illustration 1

Just under 10,000 people live in this district. On average its residents are younger and better qualified than the rest of the département. Many are in work and have children.

It is this large, sparsely-populated area just north of central Paris that has been chosen as the site for the athletes' Olympic Village for the 2024 Games and for the Olympic Aquatic Centre (CAO). One of the main stations for the future Grand-Paris-Express metro system is also due to be built there, linking all the lines that are under construction. In addition a new office and hotel district – Les Lumières de Pleyel – is planned as well as a flyover over the network of railway lines coming to and from the Gare du Nord station in Paris.

This is a busy area, criss-crossed by roads, swamped with air and noise pollution, but also a rapidly-expanding residential neighbourhood. It is this contradiction between the two which is about to turn this area into a case of major environmental injustice, one right on the edge of Paris, as many documents seen by Mediapart testify.

The plan to build a new junction on the A86 motorway is a direct consequence of the decision to close the nearby slip road access to another motorway, the A1. Once those slip roads are removed this will free up the area for the construction of a new residential and office district as part of a wider development plan.

Historically this area has seen little public or private investment. But now property, urban development and the economy have become all-important factors. In the face of this steamroller of concrete and money, little importance seems to have been attached to the concentration of nitrogen dioxide and fine particles in children's lungs.

In May this year the administrative appeal court in Paris suspended the official declaration of general interest which had justified the building of the new A86 junction and paved the way for its construction. This was because of the “negative health consequences of the project” and “its impact in terms of worsening air quality” at several sensitive sites. The court pointed to a “clear error in evaluation” as well as a lack of information given to the public during the earlier consultation process.

However on October 22nd this same court – but with a different judge – overruled its own judgement. As a result work can now begin on the site. The new ruling states that the public were in fact properly informed, even if the impact study had not taken into account the cumulative effect of all the other development work in the district, in particular all those other projects linked to the organisation of the 2024 Olympic and Paralympic Games. The court considered that “overall” the project will improve air quality. And that when it came to “socio-economic advantages” the plan to change the junctions on the A86 and A1 motorways were indeed in the general interest.

Yet the October judgement does not explicitly set out just what these socio-economic interests are. You have to delve into annex 2 of the declaration of general interest made by the Paris region prefecture in November 2019 to find them. “The project is advantageous to the local authority as its net calculated benefit is substantially positive,” the prefecture states. This stems from the fact that it “offers users optimal traffic conditions on the A86 and A1 motorways and on the local axis” says the prefecture. It will also, says the document, improve services for the Olympic Village as well as improving road safety, though it provides no proof to back this up. The prefecture - the local state office – thus concludes that “the drawbacks of this project do not seem excessive with regards the utility that it represents”.

Behind these phrases the crux of the problem starts to emerge: for the authorities the economic and social advantages of the infrastructure work are detached from their impact on the environment in which they are being built. It is true that the stated objective of “environmental and landscape integration” does appear among the criteria that determine the general interest. But it is just one argument alongside others, and not a condition.

This inconsistency in the authorities' reasoning will continue to plague the Pleyel crossroads legal case. Despite the court's overall positive verdict, the administrative court's October judgement nonetheless acknowledged that some sensitive sites “were affected by worsening air quality”. These sites were set out in line 29 of the judgement: the Marcel-Sembat and Anatole-France primary schools, the Pleyel nursery, Marcel-Cachin secondary school, the Les Sonatines early learning centre, the Dora-Maar middle school, the Pablo-Neruda stadium and also the approaches to the national sports stadium the Stade de France. According to Hamid Ouidir, a local parent and member of the departmental parents association, these institutions teach close to 3,000 children in total. There will also be additional future education establishments whose capacity is not yet known. The parents group has appealed against the Paris court's ruling and the case could go to a new hearing.

A local collective, Pleyel à Venir, has been set up to oppose the infrastructure plans and to support alternative developments in the area. One member, Benjamin, told Mediapart, that “the judge acknowledged that the project is going to produce pollution but that this shouldn't prevent it from going ahead. In the middle of a health crisis, in the middle of the Covid crisis, in the département where there have been the most deaths...”

So how is it that, despite an admission that children will end up breathing worse quality air, the project's declaration of general interest is still valid?

The reason is that the French courts have taken it upon themselves to determine the area covered by the impact study. And they have decided to look at the impact of the pollution across the whole of the project, including the building of the new junction and the removal of the A1 slip roads, and have examined both what happens at the Pleyel crossroads and slightly further away towards Paris. This wide-angle focus has the effect of removing the impact of the concentrated pollution hotspots near the schools.

The courts consider their argument is strengthened by the fact that this area already has “very poor air quality”. So even if the courts accept that some schools are “affected by a worsening of air quality” nonetheless the “majority of the sensitive establishments will benefit from an improvement”.

This glossing over of the air quality problem is achieved via a subtle semantic shift. In its decision authorising the works, the administrative judge in October attached greater importance to “atmospheric pollution” in general than to the specific concentration of pollutants in the air. By making the traffic flow better the project is expected to lead to a 10% reduction in vehicle numbers within the total area, and thus a reduction in atmospheric emissions. The court states that “over all the area concerned” - and this geographic precision is crucial – there is expected to be a reduction in the levels of benzene, nitrogen dioxide and PM10 and PM2.5 particulates. The logical conclusion for the court is: “The situation will in this way be improved overall within the boundaries of the proposed project.”

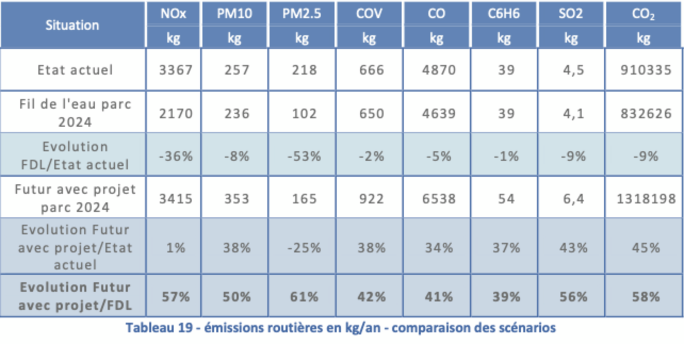

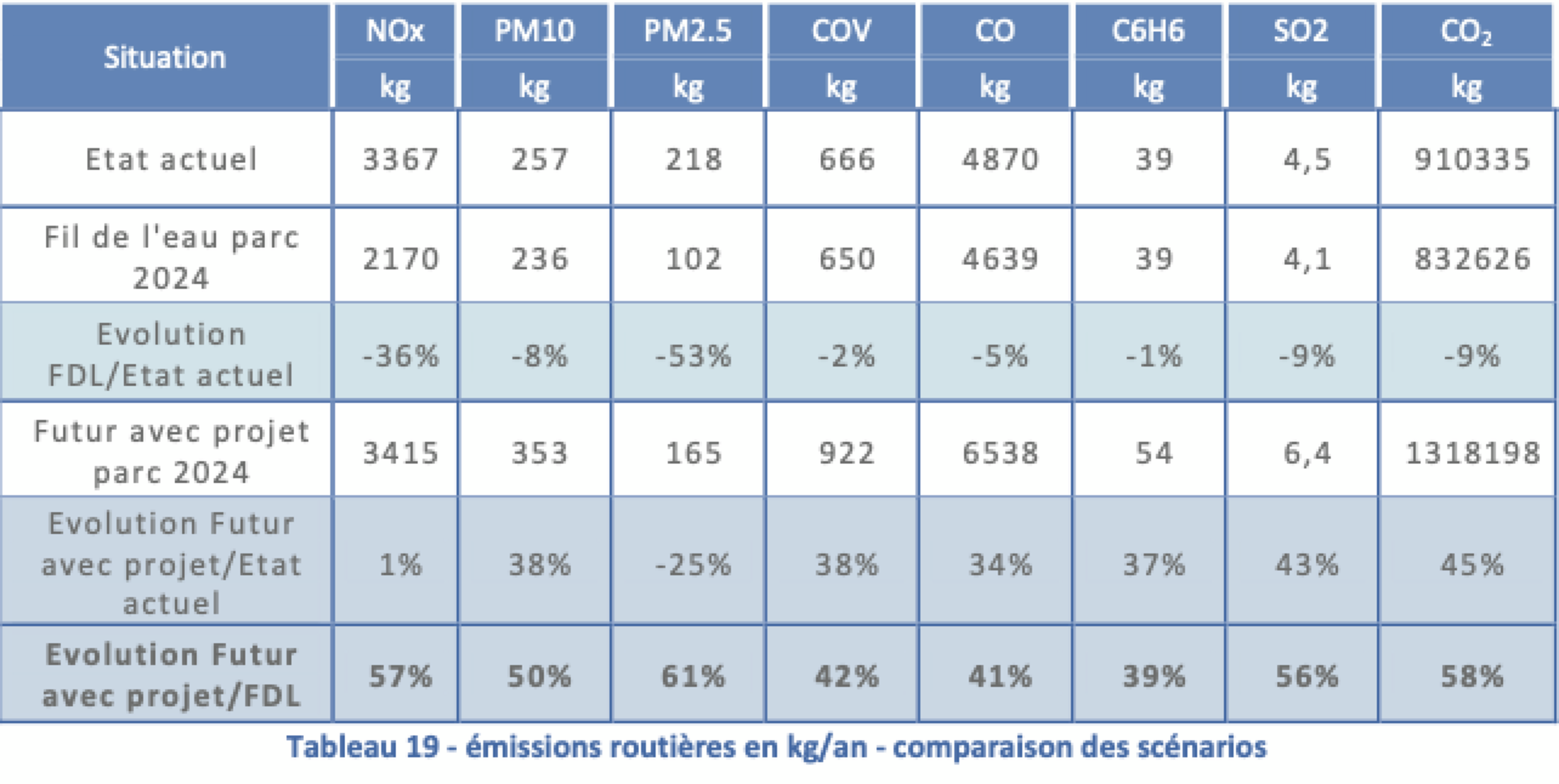

Yet several official documents, all in the public domain, demonstrate the exact opposite of what the administrative court of appeal states. The public inquiry into the Olympic Village in the summer of 2020 published a chart forecasting a rise in all air pollutants (nitrogen dioxide, fine particulates, volatile organic compounds (VOCs), sulphur dioxide and so on) on the future athletes' Village site if the junction is built. It will be served by the new slip roads on the A86 and will be located a few hundred metres from the Pleyel crossroads.

Enlargement : Illustration 3

Moreover, the environmental authority in charge, the sustainable development and environmental council the Conseil Général de l'Environnement et du Développement Durable – which comes under the control of the Environment Ministry – wrote in January 2019 that while the A86-A1 development “constitutes an improvement in relation to atmospheric emissions” the outcome was “more nuanced, however, in terms of concentrations”. This body expects to see a worsening of the situation for all atmospheric compounds compared with the current scenario.

For example, it forecasts an increase in nitrogen dioxide – whose levels are already above the regulatory threshold – and also several toxic substances such as barium, chromium and mercury. It goes on to state that “despite an overall diminution in concentrations of nitrogen dioxide in the future, some sensitive sites (in particular the Pleyel nursery school and the Anatole-France junior school) will see hourly permitted values exceeded for the scenario where there is a project”.

In relation to PM10 particulates, which are especially dangerous as because of their size they can penetrate human tissue and irritate people's airways, the “scenario with the project is higher, with an increase of 1%”, noted the environmental body.

But by basing its analysis of the likely impact of the scheme on a wide-angle approach to the project in general, the administrative court of appeal chose an analysis that favours the development.

On noise pollution the environmental body concludes that the project is going to cause “significant modification”, meaning that it will be noisier for seven buildings, including the Anatole-France school buildings south of the Pleyel junction. The noise map shown to the public inquiry into the junction also shows that, in a comparison of before and after for noise pollution, there is a clear increase in noise levels to the east of the school buildings.

'It's a form of discrimination'

As in the case of the now-abandoned airport project at Notre-Dames-des-Landes in western France, the impact studies for the various developments planned for the Saint-Denis area – the Olympic Village, the Pleyel flyover, the Pleyel junction, the aquatic centre, the Grand-Paris-Express, and the Lumières de Pleyel hotel and business area – are all separate from each other. The figures for current pollution levels also vary from report to report, pointed out the Pleyel à Venir collective, which bring together locals opposed to the new A86 slip roads.

This piecemeal approach means that no one chart can clearly show the accumulated effects of the pollution. Some projects that have not yet been carried out were also taken into account in the calculation of existing pollution, which under estimates the rise in problems they will cause. As is the case in many motorway, station or Center Parcs projects, the developers highlight the measures they will take to offset any pollution, yet provide no proof of their effectiveness.

Yet existing air and noise pollution are the result of an increase of traffic around and close to the Pleyel crossroads, and the construction of the new junction will indeed increase them.

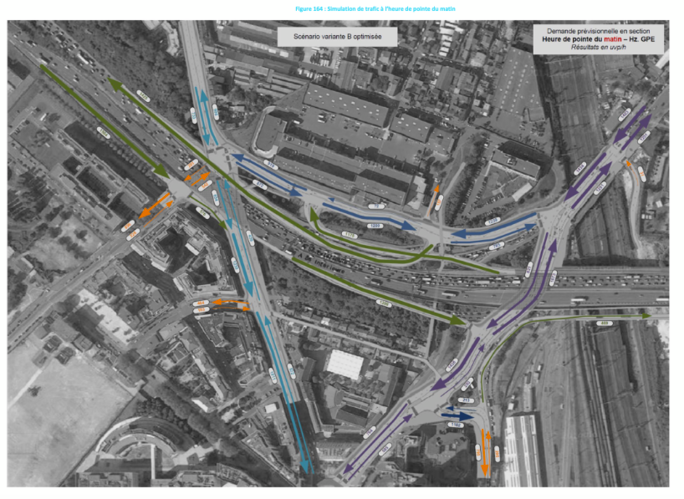

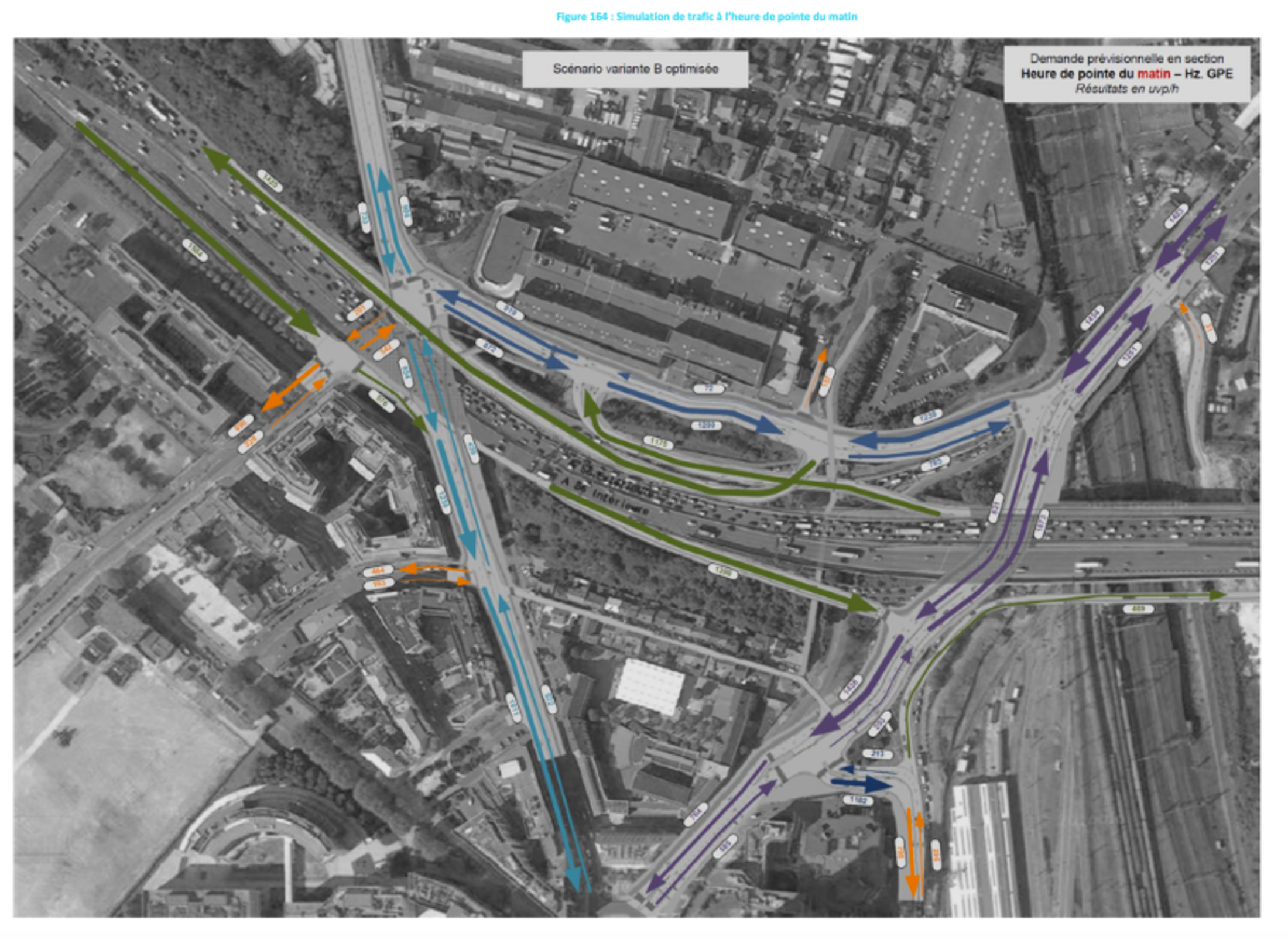

Enlargement : Illustration 4

It is here that the case gets even more complex. The groups behind the project – the highways authorities, the Ministry of the Environment and local authorities – insist that the new junction will “calm” the vehicular traffic on the boulevard which crosses the Pleyel crossroads and goes past the Anatole-France school buildings with their 700 pupils. But once again, depending on which part of the road you look at, the expected impacts are not the same. The claimed “calming” takes place at the east of the Pleyel district, in an area that is today uninhabited. According to documents already published by the authorities, this “calming” will not change the fact that an average of 20,000 cars a day travel between the area and Paris.

Another public inquiry was held into a separate infrastructure project in the area, the construction of a road bridge or flyover that will go over the railway lines that separate the Pleyel district from the rest of the town of Saint-Denis. This inquiry estimated the number of vehicles expected to use the different routes: this was close to 16,000 vehicles both ways close to the school buildings next to Boulevard Anatole-France, and another 14,500 on the other side, on Boulevard de la Libération. Basing its calculations on the information given during the 2017 consultation on that scheme, the Pleyel à Venir collective worked out that at rush hour the level of traffic was expected to increase by 125% in the mornings and by 190% in the evenings. The Paris region highways authority DiRIF (Direction des Routes Île-de-France) has disputed these figures without offering any alternative calculations. DiRIF did not return Mediapart's calls on the issue.

This rise in traffic numbers is made worse by the work planned for the Boulevard Anatole-France, to the east of the school buildings, which will in effect turn it into a slip road for the motorway. Questioned on this issue, the prefecture replied that “some specific layouts have been planned. In particular they aim to reduce the width of the lanes dedicated to motorised traffic, removing at least one lane in certain parts, and shifting the position of some others to move the vehicles further from residential areas.”

In a joint report, UNICEF, air pollution group Respire, WWF and the climate action group Réseau Action Climat recommend the establishment of low-emission zones (LEZ) close to schools and crèches. In 2018 the air pollution monitoring group Airparif estimated that a low emission zone that covered the whole A 86 area would reduce from 27% to 1.5% the number of public establishments which had to suffer pollution levels above regulatory thresholds.

The impact would be particularly marked for nitrogen dioxide and in relation to crèches and schools. Inside the zone between Paris and the A86, implementing an enlarged LEZ on the A86 and restricting the circulation of vehicles to those with category 3 stickers or below on the Crit' Air category of emissions would reduce the amount of nitrogen dioxide by an average of 9 μg/m3 a year.

In January 2021 vehicles with the Crit 'Air 4 stickers – which apply to diesel cars made before 2006 – will be banned during the daytime on weekdays in the town of Saint-Denis. Currently just vehicles with Crit' Air 5 stickers and and uncategorised vehicles (diesel vehicles from before 2001 and petrol cars from before 1997) are banned. Yet how is one supposed to believe that this will be enough to reduce air pollution, given that the figures on pollution from car manufacturers have to be treated with caution and that motorists who offend in LEZs are not currently given tickets?

“While it may be impossible to build next to sources of pollution, it is however apparently possible to bring the sources of pollution close to residential areas,” said the Pleyel à Venir collective ironically. “The residents of Saint-Denis are insignificant faced with a 'general interest' that still remains entirely to be demonstrated.”

Meanwhile the collective's lawyers have stated in writing: “The administrative court of appeal in Paris is thus sending a message to the contracting public authorities: don't worry about the impact of your projects on air quality or about the offsetting measures to implement, all that's needed are the intentions and the acknowledgements of failure that feature in the impact study.” And they predict that “contrary” to what the Ministry of the Environment has indicated “this decision [editor's note, the court of appeal decision] isn't favourable to anyone and it will forced to admit it when the state has to compensate the victims of air pollution because of its failings”.

Enlargement : Illustration 5

Does this mean the preparation work for the 2024 Olympic Games in Paris will pollute the air in one of the capital's suburbs? The Pleyel à Venir collective states that “at a time when everyone can measure the impact of climate change on their life, Madame Hidalgo [editor's note, Anne Hidalgo], the mayor of Paris and also chair of SOLIDEO [editor's note, the Paris Games delivery authority] congratulates herself that 120 'streets to schools' [editor's note when cars are banned or reduced in number next to a school] have now appeared in the capital and which enable Paris children to go to school safely and pollution-free. What a pity that the company that she chairs is financing a junction which is going to guarantee more pollution for the pupils of Saint-Denis, who are ten minutes from the Porte de Clignancourt, and for many years to come.” This group of local residents have supported an alternative plan for the Pleyel district for several years: it involves stopping it from being isolated and cut off, greater road safety and an urban park.

Parent association member Hamid Ouidir said: “There is clear discrimination here. This project will impact directly on the health of nearly 700 children aged from 3 to 12 while Paris protects its kids from the city's road traffic by reducing it around hundreds of Paris schools.”

Mouna, who is a member of the Pleyel à Venir collective and of the local association Vivre à Pleyel, said: “It's a form of discrimination in relation to Seine-Saint-Denis. We live in the same world but on the other side of the boundary of the [Paris] circular road. Doesn't it worry anyone that this project continues to disfigure Saint-Denis? Yet we could be covering the A 86, creating urban parks and setting up market gardening. The residents here want to live in something more than just a place you pass through. We're always reduced to a utilitarian function, as if there were no residents, no neighbourhood. As if we didn't exist.”

A question arises as to whether the 2024 Olympic Games really need the new junction in order to take place. Its aim is to service the athletes' village. “Its delivery – on schedule – is essential and requires keeping to the timetable defined by the Société De Livraison des Ouvrages,” said SOLIDEO about the junction, which it is funding to the tune of 90 million euros. “The project for a motorway junction at the Pleyel crossroads constitutes an opportunity to service the athletes' Village,” stated the Paris region's prefecture. “As the links between the different Olympic sites in the area are formed by local roads, the project will contribute to helping with access to the Olympic sites,” it said.

The construction project between the A1 and A86 motorways predates 2017 when the Olympic Games were awarded to Paris. In January 2014 the French state and local authorities signed a local development contract envisaging the construction of the new Pleyel junction and the closure of the slip roads on the A1 at the Porte de Porte de Clignancourt. But the money to fund the scheme came via the Olympic Games.

The chief executive officer of SOLIDEO, Nicolas Ferrand, said on October 15th 2020 that if the work on the A86 junction did not go ahead “we will have a difficult issue to tackle for Paris 2024: how we will make the Olympic Village work with its links with the A86, the Stade de France, the aquatic centre, without this junction?”. He highlighted an issue of “efficiency” so that “the athlete arrives on time at the competition” and an “issue of security for delegates who are very exposed and so there's no question of having a convoy that might stop at a red light”. The Pleyel à Venir collective regards the game as an event which is “above the law and outside democracy”.

In a bid to become more environmentally-friendly, the 2024 Olympic Games want to be “sustainable” and to leave a “legacy” to Seine-Saint-Denis département. After its closure the Olympic Village will become a new residential neighbourhood (see here and here). So the infrastructure that will be built for it, and the pollution it causes, will thus be permanent. The risk is that the complexity of the issues involved, the mixing up of different timescales and the technical difficulties of the pollution data have all merged to form a fog of unintelligibility and a lack of democratic transparency.

-------------------------

If you have information of public interest you would like to pass on to Mediapart for investigation you can contact us at this email address: enquete@mediapart.fr. If you wish to send us documents for our scrutiny via our highly secure platform please go to https://www.frenchleaks.fr/ which is presented in both English and French.

-------------------------

- The French version of this report can be found here.

English version by Michael Streeter