In the Vosges département (county) in the north-east of France, an area of low-lying, wooded mountains, local 'Yellow Vest' (gilets jaunes) protestors have taken the decision to enter the political fray and stand in local elections due next March.

The Vosges is one of four départements that lie within the historic region of Lorraine, a former industrial powerhouse which runs up to the borders with Germany, Belgium and Luxembourg. In the Vosges, the Right is the dominant political power, accounting for all the département's Members of Parliament (MPs) and Senators, and nearly all its mayors.

Lying in wait at the urns is the far-right Rassemblement National (RN) – formerly called the Front National – which, while it may be relatively invisible on the ground, locally garners a vast number of votes during national elections, sometimes taking the lead in the first round in France's two-round system of voting.

For Gilles Bilot, regional secretary of the Green party Europe Écologie-Les Verts (EELV) based in the town of Épinal, the administrative centre of the département, the leftwing parties in the Vosges are “virtually wiped out”.

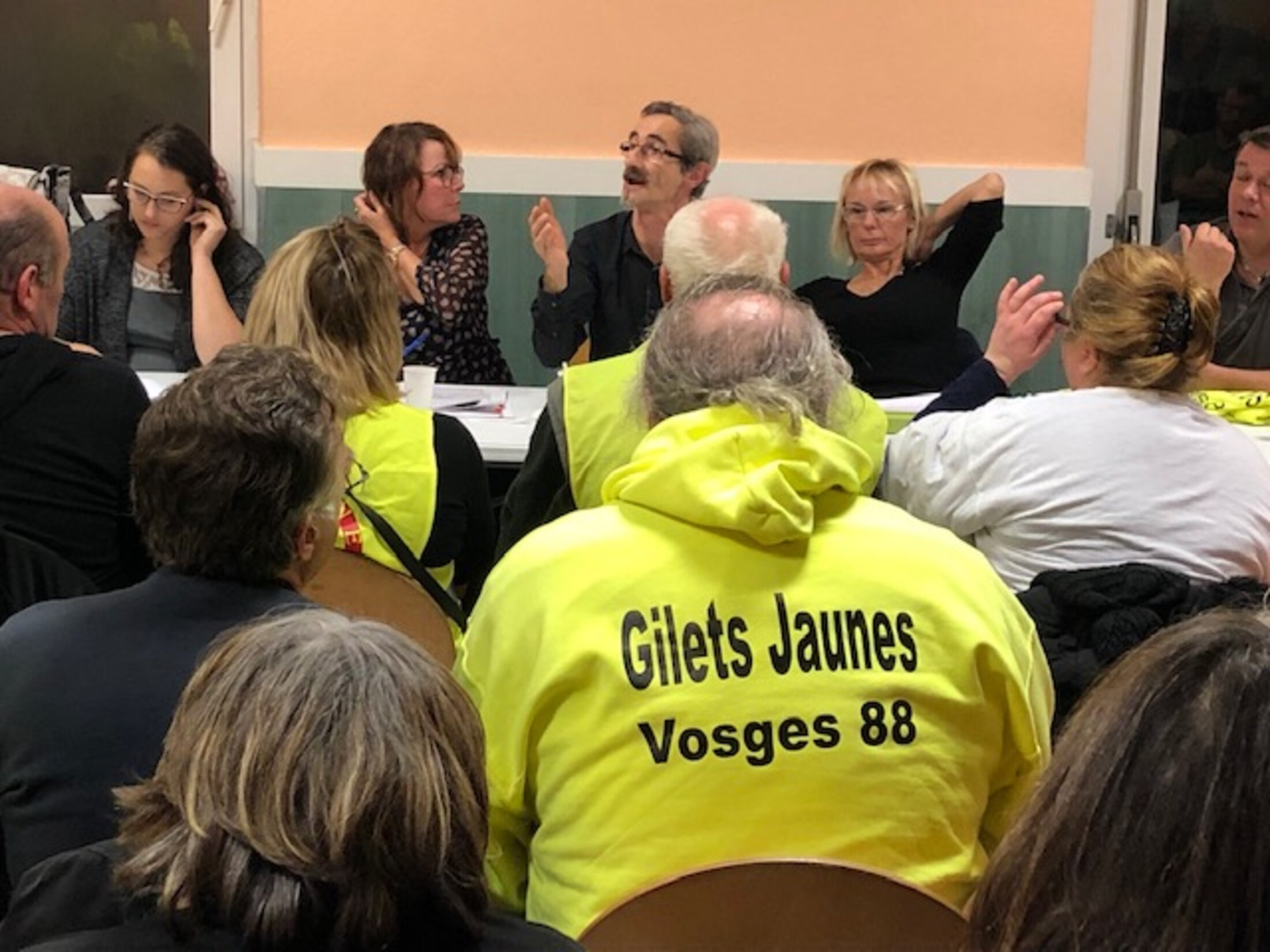

It was against this backdrop that a brand new party, Juste Gilets Jaunes, emerged from an association which unites the 'Yellow Vest' protestors in Vosges, and organised a public meeting in the village of Darnieulles, near Épinal, on November 19th to plan standing in the municipal elections in March. More than 70 people turned up, gathering in the municipal hall provided by the mayor.

Enlargement : Illustration 1

In front of the building flew a large sheet of fluorescent yellow, symbolic of the movement whose supporters wear the Hi Vis jackets which vehicles are required to carry in France. That is a legacy of the beginnings of the Yellow Vest protests, in November 2018, against a proposed hike in fuel taxes, which was marked by the occupation of roundabouts around the country.

Within weeks it became a broad, eclectic movement of protest against falling living standards among low- and middle-income earners, pensioners and the unemployed, against social inequalities, the political and social elite and for democratic reform, notably greater consultation of citizens, such as through referendums, on policy issues.

For the past 12 months, the movement, which has no single organisation and whose supporters of all ages are of different political hues, and even none, have mounted weekly, nationwide Saturday marches and demonstrations. The numerical strength of the movement, the initial strong public support for it illustrated in opinion surveys, and the disruption it caused prompted President Emmanuel Macron to announce earlier in the year a range of measures, including tax and benefits relief, aimed at cooling the anger, along with a series of local consultations across France, in which he took part, in the form of debates on societal issues.

The moves, criticised by many, not least among the Yellow Vests, as window dressing, did little to disarm the anger. While the numbers turning out for the protests, which were often marred by violent clashes with police, have latterly dwindled, there remains a strong militant base. But after a year, the dilemma of their future strategy is brought into focus by the local municipal elections to be held across France in March. Which is the context in which the Juste Gilets Jaunes (Just Yellow Vests) party in the Vosges came about.

“It was becoming inevitable,” said Gregory Brice, vice-president of the new party, before the debates began at the November 19th public meeting in Darnieulles. “In the end what we've done has always been political, defending the [lower] middle classes who've been hammered since 2008. To survive, the Yellow Vests must now evolve, put up lists of candidates, first of all at the town hall level.” In short, to embrace “politics”, a concept which has long been anathema for them.

The Yellow Vests from the Vosges initially took on more than they could handle. The municipal elections are presented as a choice between lists of candidates fielded by different political persuasions. After a fanfare in the local press about putting up candidates lists in several towns across the département, the task of finding around 30 Yellow Vest volunteers living and ready to stand in the different towns and villages they were targeting got the better of their ambitions.

In the end, said Michel Padox, president of the 'Gilets Jaunes 88' association (88 is the official administrative number of the département, which in mainland France total 95), it came down to “putting some grit” into proceedings. “If we can get a few of us into town councils, that's great,” he said.

The people running the debate in Darnieulles embraced this approach. “We want to fight on a political level, there you go, the rude word's been said! Demos are no longer possible, they're repressed too much,” said Patricia Fuhrer, the association's secretary, summing up the movement's change of course. “Before, we were like sheep. For a year now we've started to understand, to inform ourselves, to demand explanations. We have become participative citizens and there's no question of us stopping there.”

Her personal story chimes with those of the others at the gathering. Having tried to set up her own company, and having grappled with the complicated system of required social security contributions, Patricia and her husband found themselves on the verge of ruin. “Debts mounted up, the business went into liquidation, we were all over the place. I had become a loser, as they say,” she explained. “And there, on the roundabout [editor's note, many Yellow Vest protests around France have continued taking place on roundabouts, as at their beginnings] I saw a lot of people like me. People who may have crashed and burned because of divorce or redundancy.”

“Both what happened to me and the Yellow Vest movement have made me a lot more humble,” she added. “We're not nobodies, we'll never be nobodies again,” she said proudly.

The movement's public image is critical. “We have to show that we are competent, that we're not more stupid than the others,” says a spokesperson for the Gilets Jaunes 88. The movement, disrupted by police violence which has left hundreds of protestors injured, saw its early reputation lose some of its shine with the public, as well as in the media, who month after month announced its imminent end. “Today we just represent 0.01% of the population, so we're peanuts,” warned Salvatore from the back of the hall, his back to the wall. “We made a mistake at the start by blocking the roads, and straight away people were angry with us. Why would they vote for us today?” he asked. The meeting was more than anything a gathering of veteran Yellow Vests, and there were few newcomers present.

All, or nearly all, of those present at that meeting had been out on the roundabouts, demonstrating Saturday after Saturday, and had paid a price in the form of the legal and police intimidation. Patricia Fuhrer, was called in by the police cybercrime unit at Épinal over her Facebook posts. “They made clear to me that I was playing a dangerous game, that really puts the pressure on you,” she said.

Michel Padox, the president of the association, will himself appear in court in March 2020 for obstructing a road during a blockade of a shopping centre. Another Yellow Vest has to pay almost 6,000 euros in fines for having pushed a lit rubbish bin during a demonstration. A third protestor described how they faced legal action from the prefecture – the local state administration office – over social media postings. Several of those present got out their mobile phones to show screenshots of their Facebook accounts, which had been blocked because of political postings that were judged not to conform to the social media giant's rules of usage. “It's permanent censorship,” claimed Dominique, from the village of La Petite-Raon.

That anger stuck like glue to the speeches as the evening wore on. In fact, the local and national policy programmes drawn up by the association ahead of the local elections were to attract relatively little interest. Instead they were overshadowed by the flood of angry stories that were heard; the low salaries – “poor workers on permanent contracts, that's us!” – the cost of living, the spectre of retirement for some, a dislike of the elites and MPs who enrich themselves. “We've come out of our box, let them try and make us go back in!” said Michel Padox angrily. Emmanuel Macron and government representatives provoke a hatred which appears to have grown as a result of the humiliation and scorn the Yellow Vests feel they have been a target of.

In these circumstances, a collective discussion of the strategic obstacles ahead were difficult. The first of these issues is about who the Yellow Vests might ally themselves to, and for what purpose. Were there any red lines, impossible political alliances, for the Yellow Vests from the Vosges? “It's clear for us, no racist, Islamophobic, anti-Semitic, homophobic comments,” said Patricia Fuhrer. “We want to remain a movement that's open to everyone, Catholics, Muslims, gays, heterosexuals, we couldn't care less.”

However, during the evening one Yellow Vest said he wanted to take part in an opposition list of candidates from the far-right Rassemblement National party, in the town of Thaon-les-Vosges. While fellow protestors around him shrugged their shoulders and said they did not “vote the same way”, their attitude appeared to accept this as a consequence of a movement built on eclecticism. Talk then switched to a rather more animated discussion about the Yellow Vest hut on the local Chavelot roundabout, which has been destroyed 14 times on the order of the local prefecture.

The official line on the issue of alliances remains vague, even if the aim is to avoid producing election posters that are clearly partisan. “What’s important is that it brings together citizens who are angry, or Yellow Vests,” said Grégory Brice. “For me, all the rest is irrelevant. It’s a movement that has remained quite pure until now, and so shouldn’t be dirtied by whatever kind of [political] label.”

But Michel Padox believes that today, “we don’t have the choice, we must have a convergence of struggles”. He sees this above all in a gathering around a national programme that largely adopts the refrains of the Left. “But it’s hard, we no longer have confidence,” said Padox. “Take the Lubrizol catastrophe in Rouen, we didn’t hear a great deal from the ecologists. With the Socialist Party, for 40 years, the day after they’re elected they betray. So we need [to find] a certain way of guaranteeing integrity.”

Anne Heideiger came to the meeting from her hometown of Nancy, which lies in the neighbouring Meurthe-et-Moselle département. Like the Yellow Vests in the Vosges, she is a member of the coordination movement in the Grand Est (Great East) region (a newly named vast swathe of territory that encompasses the formerly distinct Lorraine, Alsace and Champagne-Ardennes regions), which has been quite successful in bringing together the different groups disseminated around it. “Ever since the beginning, I don’t think that we can draw up a “Yellow Vest” list [of candidates], we’re too different,” she said. “To be coherent, how do we make up a list together?” The activist, who works with a local authority, and who is a single mother with children, believes more in the idea of joining up with other lists of candidates “to push for our social demands”.

“For me, it’s social issues, 100 percent,” she added. “The Yellow Vests are neither a trades union nor a party. It’s a new social organisation, which wants to count at a local and national level. A thing that remains one of citizens, but organised and inescapable.” Some of the issues discussed that day in Darnieulles regularly came back to the national protest movement of strikes called for December 5th, in opposition to planned reforms of the pension system, and which the local group unreservedly called for joining in with.

But the idea of grafting onto the more traditional political entities is anything but straightforward, even concerning so-called citizens’ lists. In Épinal, local militants with the radical-left La France Insoumise (France unbowed) party readily admit this. “We don’t know them, the glue didn’t take,” said Fabrice Pisias, the party’s senior local official for the Vosges. Like other party militants, he recounted the story of a supporter of the hard-right Debout la France (France on its feet) party who, on the traditional Saturday protests by Yellow Vests, would fill their fuel tanks free of charge before they travelled up to Paris or to Nancy for demonstrations. “On the Chavelot roundabout, right close to here, there was a lot of far-right talk all the same,” said Pisias. “In the neighbouring [small] towns of Vagney or Gérardmer it’s different.”

Joining Pisias in the party headquarters situated on the upper hillside flanks of the town was fellow militant Martine Lafrogne, who was more moderate in her appraisal. “It really depends on the place, and the moment,” she said. “At the demonstration organised by the Yellow Vests in August in homage to Steve [editor’s note: Steve Maia Caniço, 24, a music reveller who died after a police charge in Nantes, north-west France], there were lots of people who were, let’s say, more on the Left,” she said. “I get the impression that it’s a rallying that comes together on discontent and not through construction. As soon as they try to construct, it becomes very complicated. Because they don’t want to find themselves blocked in a corridor, and one can understand that.”

Another France Insoumise militant present, Éric Balaud, warned of the dangers in the current political climate, as symbolised in the 2017 two-horse presidential election contest between centre-right Emmanuel Macron and far-right leader Marine le Pen. “This duel mustn’t crystallize the opposition to the president,” he said. “It’s a terrible game that’s being played out.”

The Yellow Vest phenomenon that has shaken up the past year has left political markers, as found within the programme of the common list of candidates to be presented in Épinal in March by an electoral alliance of La France insoumise, the Green party EELV, the Communist Party – and which might also include the Socialist Party: “The environmental issue is stronger than before,” said Balaud. “For example we’re demanding that the transport system in the town be free of charge. We have also included the requirement to hold local RIC [for“citizens initiative referendum”, one of the Yellow Vest movement’s demands] on major issues for the commune, and that’s new. Clearly, the idea comes from the Yellow Vests.”

In face of very divided opponents, spread over six different electoral lists, including two lists of candidates from Emmanuel Macron’s LREM party, two lists from the conservative Les Républicains party and one list for the far-right Rassemblement National, Fabrice Pisias believes that “it’s winnable” for the leftwing alliance. If the alliance wins, it would be a significant victory: the last leftwing-run council in Épinal dates back to the 1970s, when the socialists had the majority. Ever since, the mainstream Right have been in power, when the late Gaullist conservative Philippe Seguin, a senior figure in what was then the RPR party (now Les Républicains) and a former speaker of the National Assembly, the lower house, dominated the local political scene over a period of 14 years.

In the town of Gérardmer (with a population of almost 10,000), which lies around 40 kilometres south-east of Épinal, the radical-left alliance will no doubt be coloured in yellow for the March elections. On the outskirts of the town, which is bordered by a picturesque lake reflecting the nearby mountains, snow-covered in November, is the café “Les Copains d’abord”. Inside were gathered Éric, Sylvia, Annie and François, variously retired leftwing activists and supporters of the far-left Nouveau Parti anticapitaliste, the NPA, who recounted the exceptional year that has passed. They were all, at one time or another, and in their own manner, Yellow Vests. “You would find nowhere such an energy,” said Annie Cottel-Didier, who joined several Yellow Vest demonstrations. All of the group said they were staggered by the violence that accompanied the Saturday protests.

Éric Defranould, who sits on the municipal council, is a veteran of the electoral list Gérardmer Solidaire. In 1983 he ran for the elections alongside local radical-left supporters. For the next in 1989, they were joined by the communists and socialists. The alliance lasted ten years before the Socialist Party and the Communist Party went their own way, which saw the creation of Gérardmer Solidaire, a list led by Defranould which attracted nearly 13% of the vote, placing it third, in the first round of the elections in 2014. The approach of Gérardmer Solidaire is the same for the 2020 elections. “The list will have some NPA, some FI [France Insoumise], Greens and, I hope, Yellow Vests,” said Defranould. “In any case, they back us.”

Enlargement : Illustration 2

Interviewed separately, Lucien Chiriot, a Yellow Vest activist in Gérardmer, gave cautious support to the alliance. “I’m not at all NPA, it doesn’t attract me at all,” he said. “But the ideas put forward by this list interest me, so why not? One mustn’t be smothered by the parties, but rather push forward our demands as soon as that’s possible.”

Another Yellow Vest activist, Sylvia Havez, was among the small group in the café. “I met Sylvia at a roundabout, I can see her still, she’d just been hit with a truncheon in Nancy, on December 8th,” recounted Defranould, laughing.

Havez joined in: “We really spent time on these roundabouts, and even Christmas and New Year’s Day. Since then, our group has come into difficulty, principally because of a battle of egos.”

Beside her, Annie Cottel-Didier said that while the far-right had caused divisions among the Yellow Vests, “little by little” they were sifted out. Gérardmer is one of a rare number of municipalities in the Vosges to have a socialist mayor. “Here, the [far-right party] RN doesn’t hold public meetings, with scores that are half as high as in the national elections,” commented Éric Defranould. “We have an anti-racist committee, we’re very vigilant.” Annie Cottel and her brother and François underlined the proud history of the local wartime Resistance movement in the local valley, the role of the communist movement in the once flourishing textile industry, and spoke of how early 20th-century anarchist militants had found refuge in the mountains around Gérardmer.

While today the town is relatively sheltered economically thanks to tourism, the surrounding areas are struggling. “In the little rural communes there’s no work, the young are leaving one-by-one,” added François Cottel.

“I didn’t vote in the European [Parliament] elections,” said Sylvia Havez, “I don’t know if one day I’ll vote again. I don’t feel at all represented by our Members of Parliament [MPs]. And this year with the Yellow Vests has made me colder still about our democracy.” Éric Defranould sympathised. “In May, we organised a demonstration in support of the hospital in Gérardmer,” he recounted. “I questioned the MP, who had just begun speaking, to ask him how he voted during the [parliamentary] debates on the draft legislation on healthcare. He was incapable of answering, and after verification – he abstained. What hypocracy.”

For Annie Cottel, the convergence of the Yellow Vests and the parties of the Left is “not necessarily” going to happen through the elections, but rather in the context of the mobilisation behind protests; against the proposed reforms of the pension system, for example, but also, in a more local context, the opposition to a project to stock nuclear waste in an underground site at Bure, a village in the nearby Meuse département, to the west, and a similar project for highly toxic industrial waste at Wittelsheim, in the neighbouring Haut-Rhin département to the south-east. Annie’s brother François also doubts that there is an electoral path for the Yellow Vests: “There is such contempt and discredit that for one to say you’re a Yellow Vest, or to talk about Yellow Vest lists [of candidates], it immediately casts a chill. In my opinion, it’s necessary to move on to something else.”

Nevertheless, during the discussions at the November 19th meeting in the village of Darnieulles, on the outskirts of Épinal, the idea of political action at the local, municipal level found some favour. “The mayors are the only ones who are still close to the population, we should support them,” said Dominique, who plans to be among the list of candidates presented by the outgoing mayor, seeking re-election, in his tiny commune of La Petite-Raon, north of Saint-Dié-les-Vosges.

Didier Houot is the mayor of the commune of Vagney, with a population of almost 4,000, lying about ten kilometres west of Gérardmer, and close to the small town of Remiremont. “The Yellow Vests where I am, in Vagney, don’t oppose the mayor,” he said. “Quite the opposite, they know what our difficulties are, and our relations have always been very courteous. I believe that some have the ambition of taking part in the municipal elections. It’s above all so that, somewhere, they are heard.” Houot, who is not affiliated to any political party but situates himself more as a Gaullist conservative, is however not an enthusiastic supporter of the Yellow Vest cause. “The blockages, at the big roundabout near to Remiremont, were very troublesome. But this capacity to rally together, without any structure, without a leader, is something that’s surprising.”

Houot, who in professional life is a team leader at the local unemployment office, well knows the strengths and weaknesses of his territory as mayor. “On employment, we’re not so bad, there is a 9 percent jobless rate,” he said. “There are still a few firms that resist. The hardest [period], the end of textiles in the Vosges, is behind us. We’ve got forestry, carmaking […] But yes, there’s also misery, people who have only the RSA [a conditional minimum welfare benefit] to live with, that’s a reality.”

The nearest railway station is at Remiremont, which sits beside a large bus station. “But the bus doesn’t take you to the door of a firm. Without a car, it’s difficult,” said Houot. “Naturally, the rise in fuel costs shocked and mobilised people.”

Didier Houot intends standing for re-election in March 2020, and for the moment he faces no opposition group. He said he had no plans to change his political practice with regard to the Yellow Vest demands of radicalising the democratic exercise. “There is an elected council, which is legitimate,” he said. “And in a commune of a reasonable size, debate and discussion exist. I never considered myself as being part of an elite. I do my shopping in my commune, I live in my commune. I’m not distanced from people.”

If there is a real change in the local scene, it is with the effects of climate change on the environment. This autumn, the coniferous trees that cover the hills form a swathe of brown instead of the usual green of the Vosges countryside. The summer heatwaves dry the land increasingly earlier than before, and the thirsty trees lose both their shine and commercial value for the wood trade. “For a forestry commune like ours, it represents a real lack in earnings,” commented Houot, “ and it places us in an unprecedented situation; that of selling more wood and for a lower price. That’s going to present big problems in the long run for the finances of the commune.”

Back in Darnieulles, the Yellow Vests of the Vosges are preparing their future campaigns from there with the few resources they have. Because they have not got enough to fund a permanent headquarters, and in face of the difficulty in finding meeting halls, they want to buy a caravan to tour the département – repainted in yellow, naturally. “Citizens must be informed about their rights, must be accompanied in their dealings, “said Didine, a wheelchair-bound woman active in the Yellow Vest collective. “To show them that you can concretely change their lives.”

The Yellow Vests of the Vosges have been in contact with the municipal council in Saillans, in the Drôme département of south-east France, which began experimenting with a model of greater citizen participation in local decision-making after the last municipal elections in 2014. “It appears that it’s very hard, each decision becomes an affair of state,” Michel Padox told the meeting at Darnieulles, admitting that they are still feeling their way forward. “It’s a combat for the long haul that we’re leading here, Padox said. “Criticise us, but don’t massacre us.”

-------------------------

- The original French version of this article can be found here.

English version, with some added reporting, by Michael Streeter and Graham Tearse