The levels of lead found in the ground in and near Notre-Dame cathedral in Paris since the fire that destroyed it earlier this year are between 400 and 700 times the authorised maximum level, according to confidential documents seen by Mediapart. These figures are based on tests carried out by several different laboratories, including one belonging to the Paris police authority, the Préfecture de Police.

“These are levels that you just never see,” says Annie Thébaud-Mony, a scientist at France's national health and medical research institute the Institut National de la Santé et de la Recherche Médicale (INSERM) and a specialist in public health. “On polluted worksites such as a battery recycling plant, for example, the levels are a dozen times higher [than authorised levels]. Here, with levels 400 times higher, the consequences on health could be dramatic. There absolutely has to be medical follow-up care, including for the firefighters who were involved. This aftercare is especially important given that the effects on health [of lead contamination] can be differed.”

However, the authorities involved, the Ministry of Culture, the local health authority the Agence Régionale de Santé (ARS) and the Préfecture de Police, have largely kept silent about this pollution and have failed to apply measures enshrined in law to protect employees and local residents.

Enlargement : Illustration 1

The fire at Notre-Dame cathedral on April 15th 2019, which was described as a “terrible tragedy” by President Emmanuel Macron, provoked an enormous outpouring of generosity and within just a few days more than 400 million euros had been collected to help with the building's reconstruction.

The Élysée named General Jean-Louis Georgelin as its “special representative” to oversee the work's progress. According to the president the work will be carried out quickly “without ever compromising on the quality of the materials and the quality of the work”. However, the findings of this investigation suggest they are being carried out to the detriment of the health of some of those involved in the work and local residents.

As a result of the fire nearly 400 tonnes of lead - classified as a carcinogenic, mutagenic and reprotoxic(CMR) substance - which was contained in the cathedral's roof and spire, went up in smoke, polluting the remaining structure and its surrounds. As France's research and safety institute the Institut National de Recherche et de Sécurité (INRS) states “regular exposure to lead can lead to serious health consequences”. Depending on the severity, lead poisoning, caused by inhaling or ingesting lead, can cause digestive problems, lesions to the nervous system and sterility.

The authorities are fully aware of these risks. But it was not until April 27th, nearly two weeks after the fire, that the police and the health authority discreetly put out a statement inviting local residents to clean their premises using “damp wipes” and to consult their doctor if necessary.

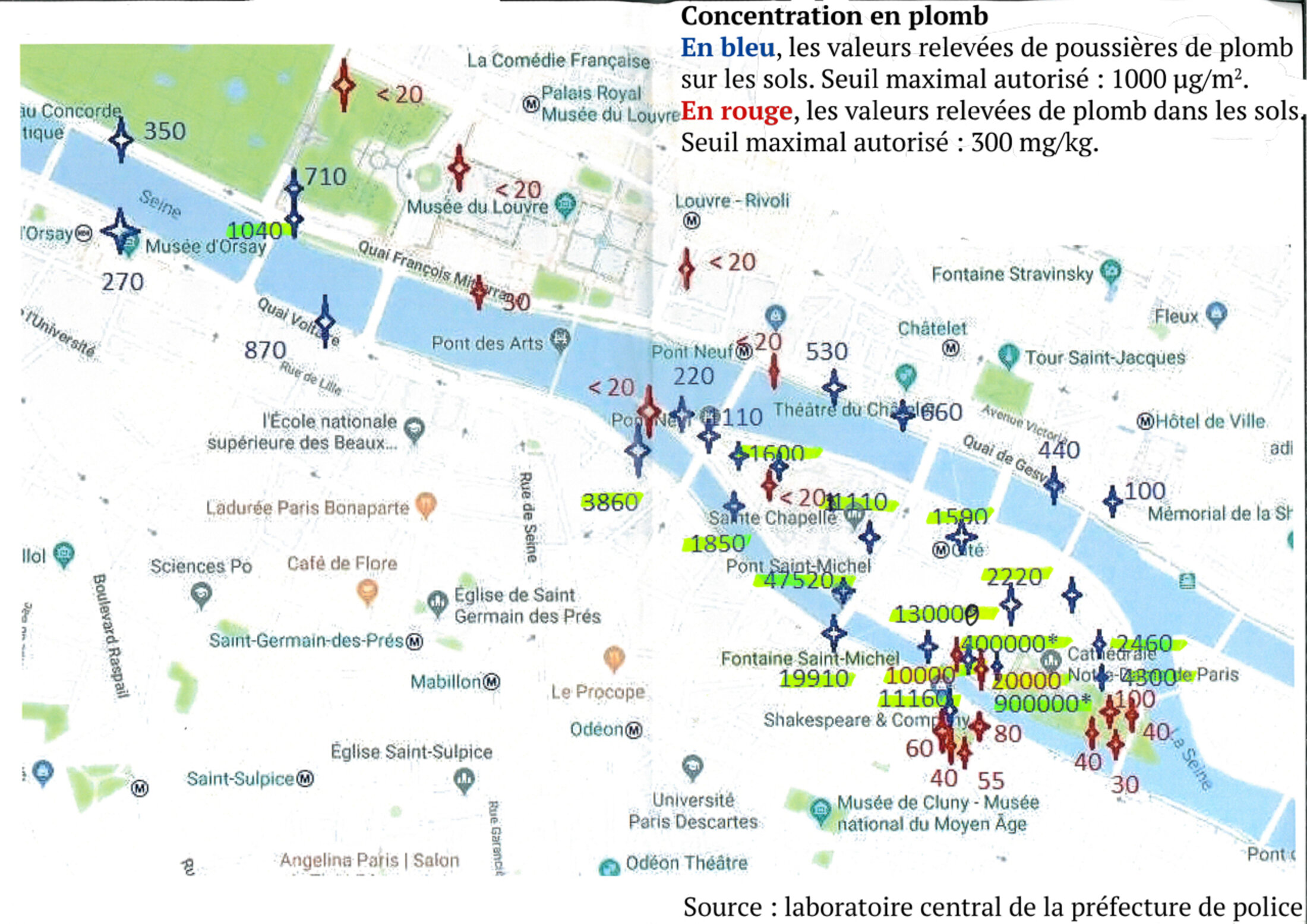

According to documents dated May 3rd and seen by Mediapart, the samples taken inside the cathedral show lead levels from 10 to 740 times above the authorised maximum level. The situation outside the structure is scarcely any better. On the cathedral square the concentration of lead in the ground is 500 times above the set threshold. Meanwhile outside the building site itself the levels on some bridges, squares or streets are between 2 and 800 times greater than the authorised level.

According to inspectors to whom Mediapart has spoken these are “absolutely exceptional levels. In general on polluted sites the levels can be 20 to 100 times above the threshold. But rarely above that. And already at that stage very strict protections must be put in place to protect the workers. Health monitoring might also be required.”

The secret of the lead levels at Notre-Dame has been well guarded, as shown by a meeting held on May 6th and details of which have been reported to Mediapart by several sources. The meeting was held at the offices of the regional health authority and it included senior figures from the Préfecture de Police's laboratory, City Hall in Paris, the anti-poisons centre, the state health insurance agency and managers from the worksite. One question that quickly arose was: should they make public the results of the lead sample tests?

Enlargement : Illustration 2

The police prefecture pointed out that some of its own premises had been affected by the lead pollution. The room for preparing bottled milk and another room in the prefecture's crèche had lead levels double the authorised level and officials said they were having to be closed for emergency decontamination work. This work was carried out soon afterwards.

But in some staff apartments at the prefecture the level of lead was even higher, at five times the authorised limit. Mediapart is not aware if decontamination work has yet been carried out in this case. New samples had been taken to check the level of contamination, the meeting was told, and these results had not been passed on to staff using these areas.

At the same May 6th meeting, the prefecture's officials explained that they did not want to publish the results of the tests so as to avoid alarming their own staff. This reluctance to pass on results was shared by the health authority, too, which said it did not want to respond to requests for information from local residents groups or environmental associations. These groups would thus have to approach the administrative body in charge of overseeing the release of official information the Commission d’Accès aux Documents Administratifs (CADA), health authority officials told the meeting.

According to one person present “the ARS was playing for time. By not passing on the results it forced the associations to approach CADA and therefore get involved in a long procedure. But once they got these samples the ARS could then say they these are old results and that the [lead levels] have gone down since. It's sheer cynicism.”

The outcome of this meeting was that on May 9th the Prefecture de Police and the ARS put out a very low-key statement which played down the risks. This was despite the fact that some samples showed lead levels 20 to 400 times above the legal threshold on much-visited sites such as the St Michel bridge and fountain, areas which were not closed to the public, or in some squares which had been temporarily closed but later reopened. In staying quiet about the dangers in this way the authorities wanted to avoid panic and getting embroiled in controversy.

When contacted by Mediapart the Préfecture de Police said that the “central laboratory took emergency samples which were sent in full transparency to the ARS for them to take the necessary measures”.

When Mediapart contacted the ARS it did not initially dispute the comments that were made at the meeting held on May 6th and said that it did not see how they posed any “problem”. However, before the article was published the ARS contacted Mediapart again and explained that it neither wanted to confirm nor deny the comments made during that meeting.

The health authority said it had taken appropriate precautions and at the request of individuals had taken some samples which has so far revealed one case of lead poisoning which was not giving cause for concern.

However, Mediapart understands that the latest samples taken on the construction site on June 13th have shown levels of contamination similar to earlier readings. Yet the various associations, including the association for the families of victims of lead poisoning, have not been provided with these results. Having failed to get them directly from the health authority, they are now having to apply via the administrative body CADA – exactly as the ARS had foreseen.

One local resident who has been campaigning on this issue explains that she has asked the health authority for details on several occasions. “But the ARS and the prefecture are remaining vague which is not reassuring for the families. If, as they claim, there's no danger then they just have to send all the results. Yet we're still waiting for them,” she says.

On the worksite itself the public authority in charge, the Direction Régionale des Affaires Culturelles (DRAC) – the section of the Ministry of Culture that is in charge of historic buildings – has not ordered any permanent health and safety measures to protect employees.

Ministry of Culture not abiding by health and safety rules

Health and safety inspections carried out on the Notre-Dame worksite have revealed that workers have received no training in how to handle lead contamination. Some are working without masks or gloves even though they are handling contaminated rubble.

The health and safety inspectors have noticed other issues too. On several occasions not only have they witnessed examples of procedural rules not being respected, they have also seen serious failings with the decontamination chambers, which are seen as crucial in protecting staff from the risk of poisoning and in stopping dust from being spread outside the site. Some of the showers in those units do not work. Even worse is the fact that some of the chambers have been placed within a contaminated area.

It is in fact possible for staff to enter and leave the cathedral site without going through one of these decontamination chambers. And outside the main site, on the polluted cathedral square where lead levels might be 500 times among the authorised threshold, some workers are operating without any protection at all.

Bruno Courtois, an expert in the prevention of chemical risks and in charge of lead issues for the INRS research and safety institute, told Mediapart that “these levels are particularly high and as it involves lead dust following a fire one can assume it concerns very fine particles that easily pass into the blood. Prevention and protection measures must therefore be reinforced to contain the lead. Crucially in such cases, the decontamination chambers stop workers going home with lead dust on them.” However, nothing along these lines has been put in operation on the cathedral site.

According to sources close to the worksite team, the Ministry of Culture – which is in overall charge of the project – is not worried that workers are walking around outside the cathedral with no protection. For this means they arouse no fears among “tourists or local residents”.

In fact, City Hall in Paris had offered to decontaminate the cathedral square, work that would have taken around two weeks at at estimated cost of 450,000 euros. For this phase of the decontamination work the workers would have worn chemical protection suits. Someone close to the case, who asked to remain anonymous, says: “Men in chemical protection suits on the cathedral square would have frightened passers-by. It would have been obvious that a danger existed.”

Instead, the Ministry of Culture preferred to take matters into its own hands and decontaminated the zone in just a few days using staff who had little protection and who did not wear the appropriate outfits. This rush to clean it means that the cathedral square is still contaminated today.

And despite reminders from inspectors, it appears the Ministry of Culture has also failed to comply with workplace health and safety rules.

On May 9th health and safety inspectors alerted DRAC – the ministry body overseeing the work at Notre-Dame – about the need to put in place measures protecting employees from the risk of lead poisoning. More than a month later the assessment from safety experts at the regional state health insurance body the Caisse Régionale d’Assurance Maladie d’Île-de-France (CRAMIF), who are also in charge of monitoring the site, was damning: “The levels of lead concentration in the dust are high and well above the regulatory threshold. The employees are therefore still exposed to the risks of lead poisoning … the facilities designated for the decontamination of the employees do not meet the provisions of the labour code.”

Culture minister Franck Riester's office insisted to Mediapart that “measures have been taken” without detailing what they were, and said a meeting had been held with the worksite management team on June 27th to ensure that everything goes “as well as possible”. But that has not resolved the issues and critics believe that the decontamination procedures remain far short of those required under the regulations.

However, as the Ministry of Culture is a public authority, health and safety inspectors can neither fine it nor place it under formal notice of compliance as they could do with private clients in other building projects.

When contacted by Mediapart CRAMIF and the health and safety inspectorate both declined to respond to questions.

Meanwhile City Hall said they had taken a series of samples in schools in the neighbourhood around the cathedral and the results, which have been published, conform with the authorised levels. As for action concerning the public spaces themselves, the city authorities said this was for the “prefecture and the ARS”. A spokesperson said: “City Hall is calling for transparency but we cannot take the place of the state.”

Officials in charge of the reconstruction project are under considerable pressure. One person involved told Mediapart that “each time the risks of lead poisoning are brought up we are told about the 'pressing urgency to secure the building'. That's how the dangers of the lead are being dismissed.”

One of the people in charge of monitoring the samples says that “state institutions are behaving like they did during the Chernobyl disaster in 1986”. At the time the French government was widely accused of being passive and not reacting swiftly to the nuclear disaster in Ukraine.

One employee at the Ministry of Culture said they regretted the way that all communications about the cathedral site were being controlled. “We don't have access to a lot of information and those who are handling it, the historical monuments service, are known for not saying much, unlike the archaeologists who speak up if there's a problem. So there's a code of silence.”

This “code of silence” suits the government and health authorities perfectly. But behind the scenes there is disquiet and some companies contacted by Mediapart are worried about being made the “scapegoats” if there is a scandal. “They are already trying to put responsibility for the fire on us,” says the boss of one firm. “There's enormous pressure being put on all those involved and the Ministry of Culture isn't even accepting its responsibility as a contracting authority. Nothing is being done to protect the health and safety of the workers. They're asking us to do the work that the client should normally do.”

Legislation concerning Notre-Dame that is in the process of being adopted in Parliament will set up a public body that will be grant exemptions from some city planning and environmental protection laws. On the worksite itself this prospect worries many of the people involved who fear that, accompanied by a complete lack of transparency, it will only increase the risks to people's health and to the environment.

-------------------------

If you have information of public interest you would like to pass on to Mediapart for investigation you can contact us at this email address: enquete@mediapart.fr. If you wish to send us documents for our scrutiny via our highly secure platform please go to https://www.frenchleaks.fr/ which is presented in both English and French.

--------------------------

- The French version of this report can be found here.

English version by Michael Streeter