Yann Gboho is a highly talented attacking midfielder in the France national under-18 team, but unfortunately for him, before his name will eventually become widely known for his skills as a footballer it is about to become associated with a racial discrimination scandal.

For when he was just 13-years-old, despite recognition of his early footballing skills, French club PSG made no move to recruit him to their youth academy for the only reason that his skin is black.

Enlargement : Illustration 1

At the time, news of this was leaked inside the club, but the management succeeded temporarily in stifling the affair. After a lengthy investigation based on information provided to the Football Leaks project (see more in 'Boîte Noire', bottom of page), Mediapart and French TV current affairs programme Envoyé spécial, produced by public channel France 2, have discovered that the club’s management in fact decided to cover up those implicated in the scandal, despite the account now given by PSG.

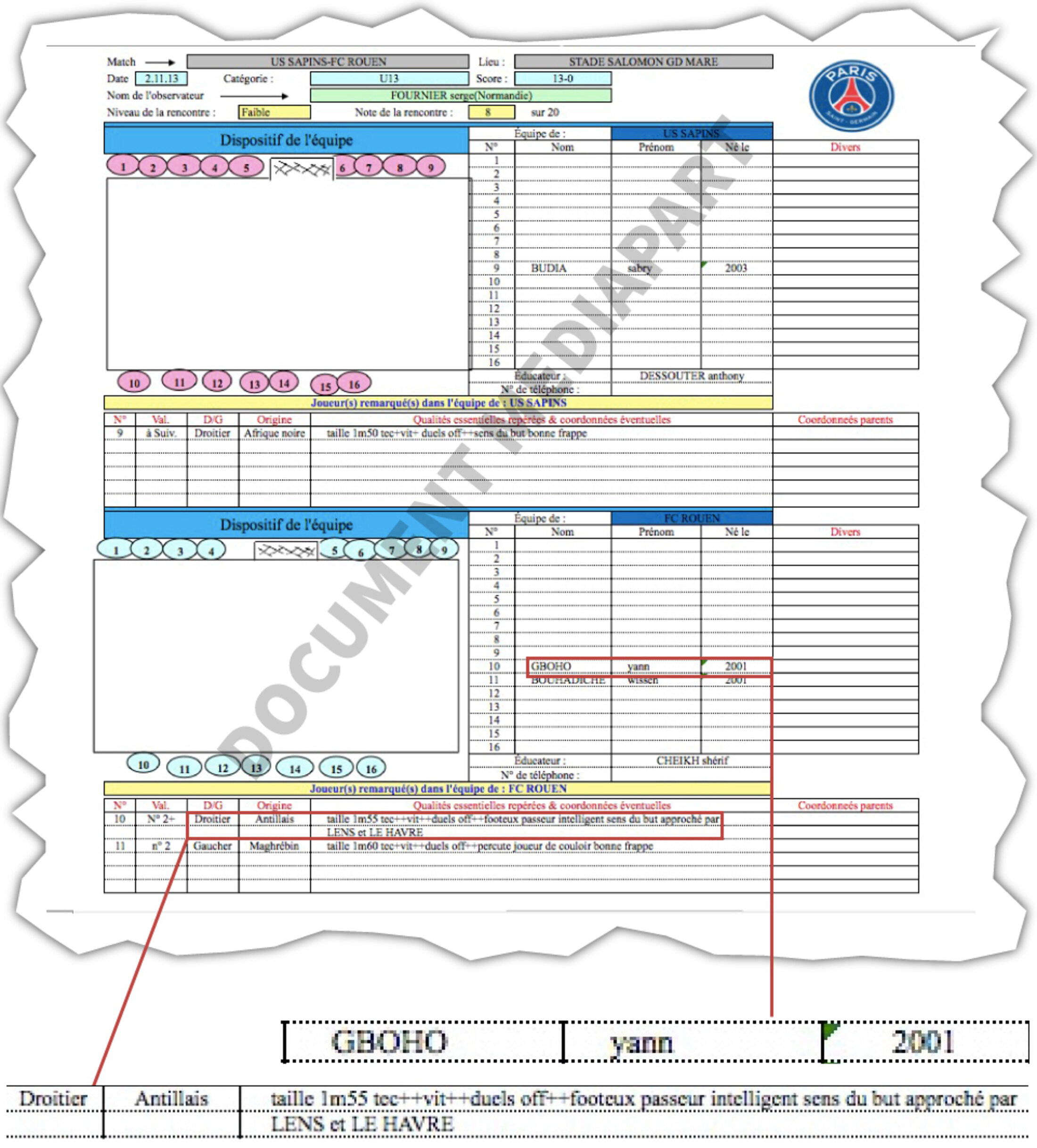

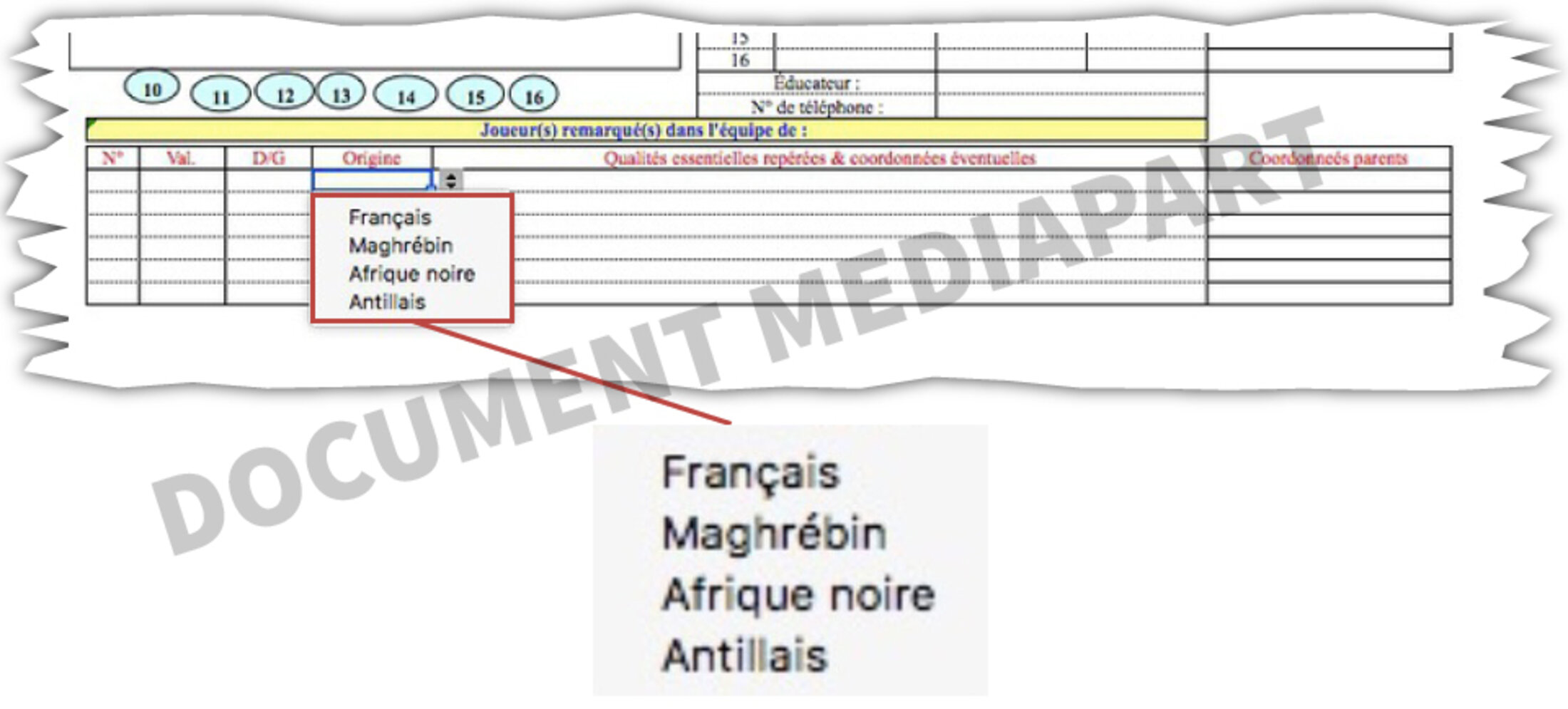

The investigation has also found that up until the spring of 2018, PSG continued to ask scouts involved in the identification and recruiting of talented young players to indicate the “origin” of the youths according to four categories: French (“Français”), North African (“Maghrébin”), West Indian (“Antillais”), and Black Africa (“Afrique noir”). It was a veritable ethnic identity file.

Enlargement : Illustration 2

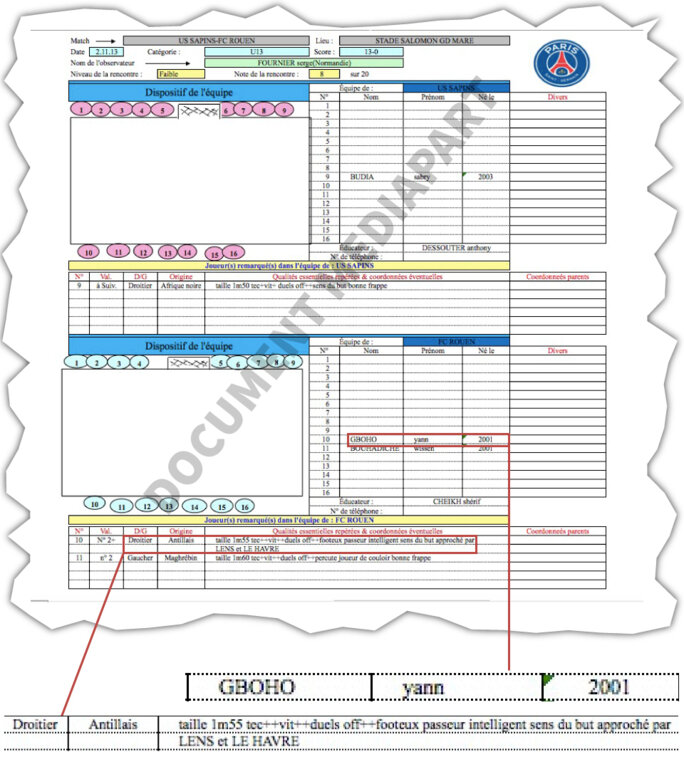

The controversy erupted within the club in March 2014. Yann Gboho, then aged 13, was playing with a team managed by FC Rouen in Normandy, and he displayed an unusual and well recognised talent. A number of youth coaching academies were keen to take him on, beginning with the most prestigious of them all in France, at the French Football Federation’s Institut national du football (INF) at Clairefontaine-en-Yvelines, south-west of Paris.

Understandably, “the technicity”, “the speed”, “the eye for the goal” of this “intelligent passer” also impressed Serge Fournier, PSG’s experienced scout for the Normandy region. In a document obtained by Mediapart, Fournier gave Yann Gboho a “2+” rating, the closest to the top rating of “1” – which is reserved for most exceptional talent. “You only put a ‘1’ for an Mbappé,” explained Fournier, 73, referring to France’s star forward Kylian Mbappé, 19, who is recognised worldwide as one of the most promising players in football. “In all my career,” added Fournier, “I’ve never given a ‘1’.”

The online report files to be filled in by the PSG scouts feature a number of subject areas under which they must evaluate and describe the players, including “essential qualities”, whether they are left- or right-footed, their shirt number, but also their “origin”. When a recruiter clicks on this tab, a window opens with a list of four choices: French, North African, West Indian, and Black Africa.

Enlargement : Illustration 3

Serge Fournier said he has always filled in this part of the player information report without paying much attention to its implications. When it was suggested to him that, beyond even the principle in France that a register of ethnic origin is condemnable practice, the description “French” appears at the very least ill-chosen, it took a few moments of thought before he answered: “Yes, there should have been written ‘white’. All the more so because all the players we recommended were French. PSG didn’t want us to recruit players born in Africa, because one is never certain about their dates of birth.”

Enlargement : Illustration 4

Two years after he first recommended the recruitment of Yann Gboho, Fournier did so again. This time, in the space on the report dedicated to ethnic origin he indicated “Black Africa”. By this time, Gboho had been recruited by the Rennes football club Stade Rennais.

Serge Fournier was unaware, or now pretends to have been unaware, that in between times the name of Yann Gboho had caused a stir at PSG, as illustrated by an internal club report about a meeting on coaching activities held on March 14th 2014. Around the table at that meeting were seven people responsible for recruitment and coaching of young players at PSG, and who included Marc Westerloppe.

Westerloppe arrived at PSG in 2013 on the behest of the club’s sporting director Olivier Létang, with whom Westerloppe was close. He was appointed head of player recruitment for all of France, except for players in Paris and its close surrounding region. After the departure of PSG’s previous sporting director, former Brazilian footballer Leonardo, in 2013, Létang and Westerloppe created a team of recruitment scouts who travelled around the country with the same player report files as used by Fournier. Westerloppe had brought the model with him from his days at club RC Lens, in north-east France.

Enlargement : Illustration 5

The following are the minutes of the March 14th 2014 meeting, the authenticity of which is not contested by PSG, contacted before publication of this article:

“Questioning about the U13 midfielder from Rouen, Geboho [sic], excellent profile about whom Marc Westerloppe delays positioning himself.

- Marc Westerloppe: We won’t return to this subject, doesn’t want to pass off as the ugly duckling. There is a problem on the orientation of the club, a balance is needed on the mixing, too many West Indians and Africans around Paris.

- Saad Ichalalène [coach for youth teams]: What mixing are we talking about? Ethnic? Cultural? Religious? Social? For the latter there is no problem.

- Bertrand Reuzeau [head of the training academy]: The best profile must be found for the top level, that’s all.

- Marc Westerloppe: If the recruitment has been opened up to the national [level, from across France], it’s a pity to find the same profiles that are already around Paris, it’s a request from the management.

- Pierre Reynaud [in charge of youth player recruitment in Paris and its surrounding region]: except that it should not be an ethnic question but about talent.”

The last note in conclusion to the minutes read: “Rowdy debate follows.”

That meeting on recruitment strategy based on skin colour ocurred three years after Mediapart revealed in April 2011 how the French Football Federation (FFF) planned to limit the numbers of minors with foreign family origins from joining its youth training academies.

The federation's National Technical Board (DTN) had officially hatched the plan for two reasons. One was that players with dual nationality, and trained in France, could in theory later decide to play for another national team. The other was about physical criteria; Mediapart revealed how the then senior France team coach, former defender Laurent Blanc, argued at a DTN meeting that there were too many black “large, powerful, strong” player stereotypes in training academies.

No disciplinary action, nor even a simple warning

But, three years on from those revelations, and which prompted a ministerial inquiry, the management at PSG did not even attempt to justify its discriminatory recruitment system. The argument heard at the FFF over dual nationality was of no pertinence for a club, while Yann Gboho, contrary to the “large, powerful, strong” stereotype once described by Blanc, was just 1.55 metres-tall. Today he measures 1.73 metres and weighs 63 kilos.

Enlargement : Illustration 6

Shocked at the club’s approach, and echoing some of the comments recorded from the March 14th 2014 meeting, several PSG scouts took the issue to the PSG’s works council and raised their objections at a new meeting held on May 16th 2014. The club’s management claimed there had been a misunderstanding, but the secretary of the works council wrote to PSG’s then director of human resources, Céline Peltier, into which were copied a several of the training staff.

“All the participants in our meeting were unanimous regarding what was said on March 14th last by M. Westerloppe, and this in the name of the club’s management,” the secretary wrote. “I found a team that was shaken, particularly affected by what could appear to be the new philosophy of our [club]. Impossible to lend support for this 180° turn!!!! None of my colleagues involved in training or pre-training can believe it. Their decision to bring this subject up again is the proof of their comittment to Paris Saint-Germain: they are intent on protecting the values upheld by the club until now. I am intent on supporting them with that great idea. I think that it is absolutely necessary that our management officially positions itself.”

There was considerable concern, especially given Marc Westerloppe had said the order for the recruitment profiling system came from the club’s management. During a meeting of the works council on June 3rd 2014, one staff member, Younousse Elboussahni, asked if Westerloppe’s comment referred to the, “sporting management or senior management?” He added: “I’m telling you that some of our colleagues have been fired for less than that. I remind you also that the club was sullied for statements of that kind in the past and it firmly decided to combat racism, anti-Semitism and all discrimination.”

“I’m afraid that this incident goes too far, and that it tarnishes the image of the club,” continued Elboussahni. “I would like this business to remain within the club but I’m fearful that, in desperation or by pique, staff will speak to the press.”

PSG administrative and financial director Philippe Boindrieux made clear what the club’s reaction in such a case would be: “We will not hesitate to discipline employees responsible for a leak in the press, because it is unacceptable to use the press and the image of the club to achieve one’s ends.”

In sum, those who expressed in public their concern over practices of discrimination would be punished. But what about those who initiated the scheme and those who put it into practice? The issue caused strong debate within PSG, as demonstrated by the Football Leaks documents, and notably at a meeting on June 16th attended by the club’s general manager Jean-Claude Blanc and human resources (HR) director Céline Peltier.

Blanc, the second-highest management figure at PSG after its president Nasser Al-Khelaifi, was informed during the meeting that the comments made by Westerloppe, which placed him liable to prosecution in France, would justify his sacking. But Blanc was concerned about the repercussion that would have within the club, and notably feared it would weaken the position of sporting director Olivier Létang, Westerloppe’s superior.

Furthermore, according to HR director Céline Peltier, similar comments had been made by Létang himself at different meetings, and if Westerloppe was sacked he might say that the instructions came from above.

Peltier also underlined that a document had been given to training and recruitment staff in which they are asked to report on player’s ethnic backgrounds – the very same report sheet mentioned at the beginning of this report. She was concerned that this might become leaked to the media.

The club’s management concluded that firing Westerloppe might not be the solution to the problem. However, it was decided that he should be called to a meeting prior to disciplinary action, which could lead to his sacking, and to judge the situation from there.

Enlargement : Illustration 7

During that meeting, held on June 27th, Westerloppe told Jean-Claude Blanc that the accusations levelled against him were “false, malevolent and stupid” and that he was deeply hurt by them.

The club decided to take his side and told staff that the minutes of the March 14th 2014 meeting did not reflect Westerloppe’s thinking and that his words had been distorted. No disciplinary action was pronounced, nor even a simple warning, and Westerloppe was cleared of wrongdoing.

Questioned by Mediapart, Westerloppe first claimed that the minutes of the March 2014 meeting was a false document – although the club does not dispute its authenticity. Finally, both Westerloppe and Létang changed their response, arguing that “this business is the concern of PSG”

That reply might be interpreted as suggesting that the instructions came from above, which we Mediapart was also told by several player recruitment staff. If so, the question remains over who precisely might the instruction come from. Furthermore, given the concern the issue caused within the club, could PSG’s president Nasser Al-Khelaïfi, head of the club’s principal shareholder, Qatari Sports Investment, have been unaware of the controversy?

After hesitating for several weeks over Mediapart’s request for an interview, PSG eventually fielded not its general manager Jean-Claude Blanc but former Socialist Party Member of Parliament Malek Boutih to answer questions. Before becoming a socialist MP in 2012, Boutih was president of the French anti-racist organisation SOS-Racisme, from 1999 to 2003. He explained that he has worked for the past 15 years as an advisor on racism issues within a foundation belonging to PSG.

Speaking on behalf of the club, Boutih confirmed the existence of the ethnic reporting, but said that the system had been operated in secret and that the PSG management was unaware of the practice, adding that they discovered it only after Mediapart had approached the club on the subject. “Honestly, the ceiling fell from above them,” Boutih said. “For them, it’s like a stab in the back. There is a real problem which they are not responsible for. There is no desire for a code of silence. Jean-Claude Blanc was not aware of the existence of these forms.”

The ultimate sporting irony for Yann Gboho

Asked about Marc Westerloppe’s comments that instructions came from the management, Boutih said, “It was a way of hiding”. As to why Westerloppe, at least, was not sacked, he replied that at the time, “no-one produced the slightest evidence, no-one confirmed the comments made to Jean-Claude Blanc. He asked [for this], everyone kept quiet.”

However, the reports of the different meetings held within the club, as detailed earlier in this article, prove the opposite. Staff had objected to the system on several occasions, and the management knew that there were grounds to sack at least one employee for serious professional misconduct. More still, the management had been informed that similar comments to those of Westerloppe had been made by sporting director Olivier Létang, and knew that the forms detailing youth players’ ethnic origin were circulated among the scouts.

Enlargement : Illustration 8

Given this, had Blanc not, at the very least, attempted to bury the scandal to prevent it leaking out? “He is the sort of man for who fear of scandal is less serious than to lose his honourability,” replied Boutih.

If PSG admitted that management knew of the existence of the forms in 2014, it must explain why no disciplinary measures were taken, and also why no effective action was taken to put an end to the practice. For Mediapart has learnt from numerous current and former player scouts of the club that these same reports detailing the ethnic origins of players were used up until the spring of this year (see below one such document completed in January 2018). “I must have filled in more than 700 forms like that,” said Serge Fournier.

Enlargement : Illustration 9

Furthermore, these same forms were still in use for almost a year following Olivier Létang’s departure from the club, and for several months after Marc Westerloppe left. There would appear little purpose to the continued reporting of ethnic origin of young players unless it remained a criterium in the recruitment of young players.

Mediapart questioned several scouts about how they proceeded with this, and how they interpreted the demands made by the club.

One of them explained why more white players were needed: “We were looking for players who provided something extra in terms of intelligence in the game. And then, if you put people from the same community, if out of a group of 23 players you have 20 blacks, you’re in difficulty concerning their management. If the guys begin a boycott of the group, you’re done for. If you have only blacks or beurs [of North African family origin], it’s very complicated. When you build a team it’s important to have this mix and to control it.”

Another scout commented: “When I was at PSG with Marc Westerloppe we didn’t look for black, strong etc. [player] profiles. We looked more for footballers with a very good technicity and playing intelligence.”

Yet another said: “The management in Paris had put the cards on the table by announcing that there should be more or less a tendency to take some whites in relation to blacks. But on the playing fields in my region, out of 40 kids you have 35 blacks and greys. That’s all, it’s a France that’s like that. They are with us, we accept them. Marc accepted the instructions that he might be given, because Marc isn’t the type of person to take on responsibilities without having been covered by someone above. If Jean-Claude Blanc hadn’t leant support to Marc and Olivier Létang, Westerloppe would have been pushed out of the [recruitment] group a long time ago.”

According to research by Mediapart and Envoyé spécial, only one black player was recruited between 2013 and 2018 by PSG’s provincial scouting network. But the truly pertinent question lies elsewhere: how many youths, like Yann Gboho, did not receive an offer from PSG because of the colour of their skin? The answer to that is impossible to establish because the victims of such a system are unaware that they did indeed fall victim to it. After publication of this report, how many young players will be asking themselves if their ethnic origins are the reason that one of France’s most prestigious football clubs, and currently the most successful, snubbed them?

Enlargement : Illustration 11

Lilian Thuram, the former France defender who retired ten years ago after a prestigious playing career at European club and national team level, is an outspoken campaigner against racism in sport. “What you show me and have me listen to is extremely serious,” he told Mediapart. “Recruiters watch a child play and they only see the colour of his skin. Imagine for a moment the reverse case: I am a manager, I decide to no longer recruit whites, and that gets out in the press. I’d be slaughtered in public.”

“It’s surrealist,” added Thuram. “We are in 2018, we’ve won the World Cup. There was the case of the quotas [editor's note: the plan to filter players at French Football Federation training academies on grounds of ethnic origin, as revealed by Mediapart in 2011], and here I learn that there are people within PSG who did that over several years. Up until 2018. It’s crazy.”

“In the beginning, it is individuals who set up a discriminatory policy, not the institution,” Thuram said. “But when the club learns what happened, those people must be eliminated. Straight away. The institution goes about saving its image, to not rock the boat.”

The abject immorality and also the legal implications of such recruitment methods are all the more absurd regarding any logical considerations in that they also deprive the club of talented players, as the subsequent story of Yann Gboho demonstrates.

In 2015 he joined the training academy of the Rennes football club Stade Rennais. In June this year he scored for Stade Rennais in its victory over PSG in the semi-final of France’s U17 team championship. He scored again in the subsequent final against Toulouse, won by Stade Rennais 2-0.

The story might have ended on that upbeat note, and the promise for Yann Gboho of a successful career ahead after joining the first team of Stade Rennais, now playing in Ligue 1 but also in this season’s Europe League tournament.

Except that in November 2017, just a few months after Gboho had signed his first professional contract, with the Breton club, Olivier Létang, who in June last year had left PSG for reasons unconnected with the controversy over the discriminatory recruitment policy, was appointed president of Stade Rennais. Létang in turn signed up his loyal lieutenant Marc Westerloppe as head of “the monitoring and individual development of players”.

Contacted during this investigation by Mediapart and Envoyé spécial, Létang declined to answer the question as to why he recruited the man who was at the heart of the scandal that erupted at PSG.

Yann Gboho, who has played no part in the revelations reported here, now plays for a club with a staff member who chose four years ago not to recruit him because of the colour of his skin. While his club’s boss is he who at that time was PSG’s sporting director, and who oversaw the same policies for recruitment of youth players.

-------------------------

- The French version of this report can be found here.

-------------------------------------------------------------------------

If you have information of public interest you would like to pass on to Mediapart for investigation you can contact us at this email address: enquete@mediapart.fr. If you wish to send us documents for our scrutiny via our highly secure platform please go to https://www.frenchleaks.fr/ which is presented in both English and French.

----------------------------------------------------------------------