Enlargement : Illustration 1

A major work just published in France charts a history of the country's black population, beginning in the late 17th century, compiling more than 700 documents, many of them never released before. La France noire, trois siècles de présence, (‘Black France, a presence over three centuries') is a unique project which is to be accompanied by an itinerant exhibition on the same subject that will travel around France early next year, while a three-part documentary film based on the research for the book is to be broadcast on the Franco-German TV channel Arte, beginning on January 5th.

"Work on the history of blacks in France is not new, hundreds of books have been dedicated to their subject, but they have often remained on the

Blanchard paid tribute to a book published in 2008 by the French historian Pap N'Diaye, La Condition noire, essai sur une minorité française, (‘The black condition, an essay about a French minority'), which was the first to explain that a unique, common identity does not exist, but rather that there is a common condition with regard to history. "Without this book, we'd have had a hard time producing ‘Black France'," he said. "In France, people think that to produce a history of a population creates a community. If you centre on workers, you create a class. If you work on blacks, you create a black community. In the United States you can work on a group, without for as much considering that this constitutes an identity or a community."

"The book shows that several histories intertwine. The history of Malagasies in France is not that of Mauritians in France, which is not that of Senegalese in France, nor that of Guyanese in France. But in the way these communities are regarded, from some political and cultural stances or in certain judicial rulings by the State across history, to be black had a collective significance," said Blanchard.

He dismisses the suggestion that the book is in some way a French take on ‘Black Studies', the teaching of the history of the black community in the US and which was born from the civil rights movement. "This history doesn't come from an importation of Black Studies, but from an inter-crossing over the last 25 years of people who work on colonial history, the history of immigration and the history of [social] attitudes," he said. "It does not come from a political demand."

Yet when the Black Associations' Representative Council, the Conseil Représentatif des Associations Noires de France, the CRAN, was formed in 2005, it laid claim to a Black identity. "The CRAN is the visible part but it is not new," Blanchard said. "What is the difference between the CRAN and the Comité de Défense de la Race Nègre [Defence Committee for the Negro Race], which dates from the mid-1920s? We think the CRAN is a novel phenomenon because our knowledge of the history of France and its black population is poor. There have always been times when minorities which find themselves excluded, involved in political struggles or seeking legitimacy organise and assert their identity."

The book follows recent historical works in tracing the presence of black people in France back to the 18th century, nailing the myth that blacks are recent immigrants who have difficulty integrating culturally with the host population. However, it does not try to avoid some less palatable sides of this history.

Blanchard says the book, which contains a plethora of photographs, is like a photo album. "You find everything in a family album," he said. "You don't take out photos that upset some people. These are historical documents."

"We also talk about [France's first black parliamentarian] Blaise Diagne inaugurating the Colonial Exhibition of 1931, and about Gratien Candace, the deputy from Guadeloupe who supported the Vichy regime, or about René Maran, poet and writer from Martinique who won the Prix Goncourt [France's most prestigious literary prize] and who ended his journalistic career on [pro-fascist magazine] Je Suis Partout."

Blanchard said the book aimed to give the lie to two specific myths surrounding the presence of blacks in France. The first simply excludes them from history, "as if Africans, West Indians, people from Guyana and [French Indian Ocean island] La Réunion had never taken part in the history of France," while the other has been adopted by some descendants of early arrivals "who think that all Blacks in France were French versions of Malcolm X".

Over the following pages, Pascal Blanchard commentates for Mediapart a selection of photographs and illustrations from the book.

Colonial fears fed early myth, reality defied stereotypes

Enlargement : Illustration 2

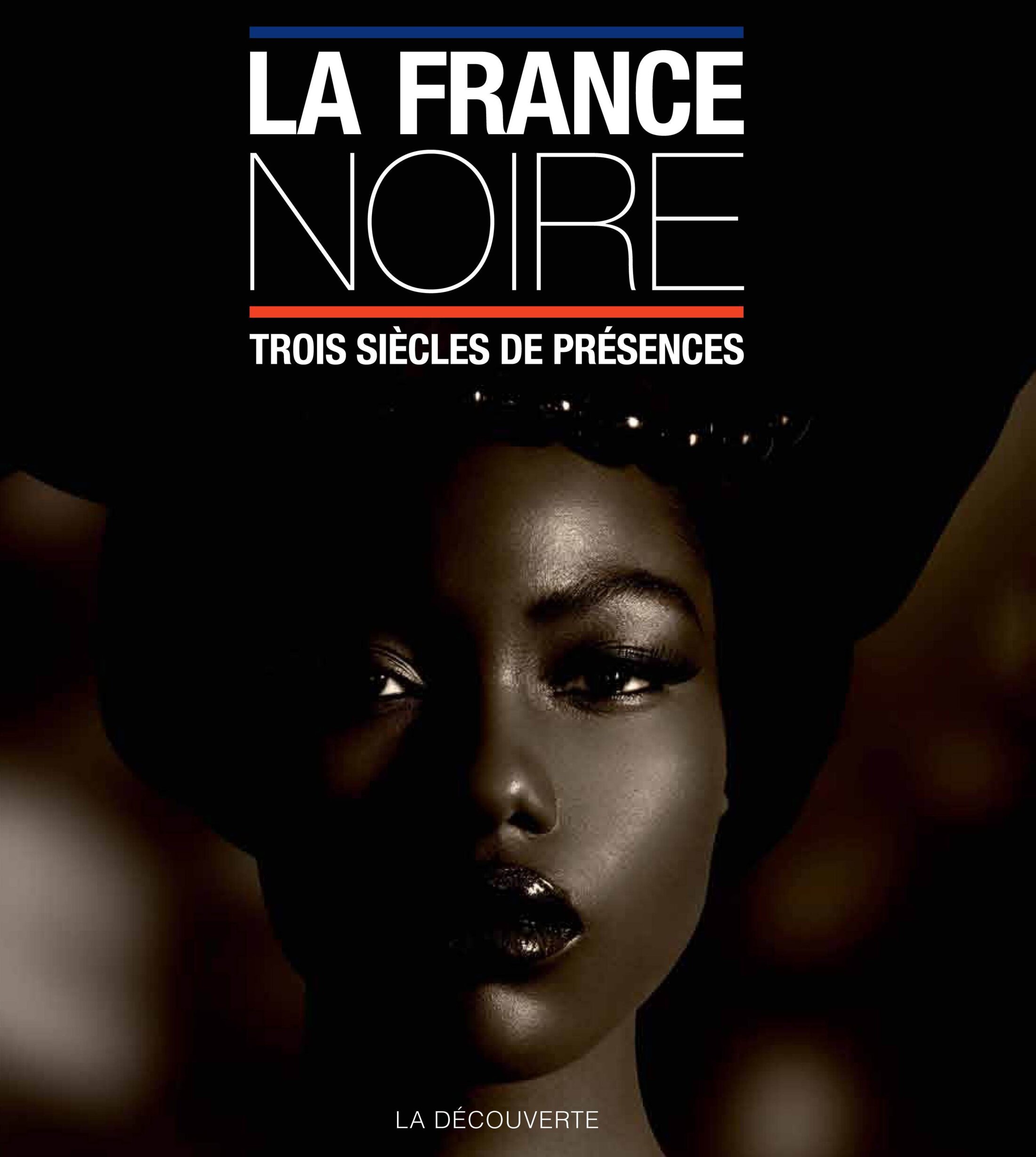

Pascal Blanchard: This [right] is the cover of a book published in 1895 which was a best-seller at the time. The famous Capitaine Danrit [the alias used by Émile Driant], L'Invasion Noire [The Black Invasion] relates an incredible story. Muslims rally masses of Africans to invade France, and in particular Paris. So the idea of an African invasion of mainland France goes back a long way.

It met with enormous success and there were posters promoting it across Paris. The cover picture is interesting because it embodies a widely held belief that can be summarised as follows: even though France is a major colonial power, if we are not careful, the masses will invade us tomorrow and Paris will burn.

The book's ending is pure fantasy, because "we" end up sending them back home, "we" colonise them and "we" make them stay in their homelands.

So in this book and its cover picture can be found all the myths that would characterise popular consciousness during the 20th century - fear of invasion, fear of racial mixing and fear of Islam. And all the fantasies about blacks being bloody warriors who steal women - savages, in short.

Enlargement : Illustration 3

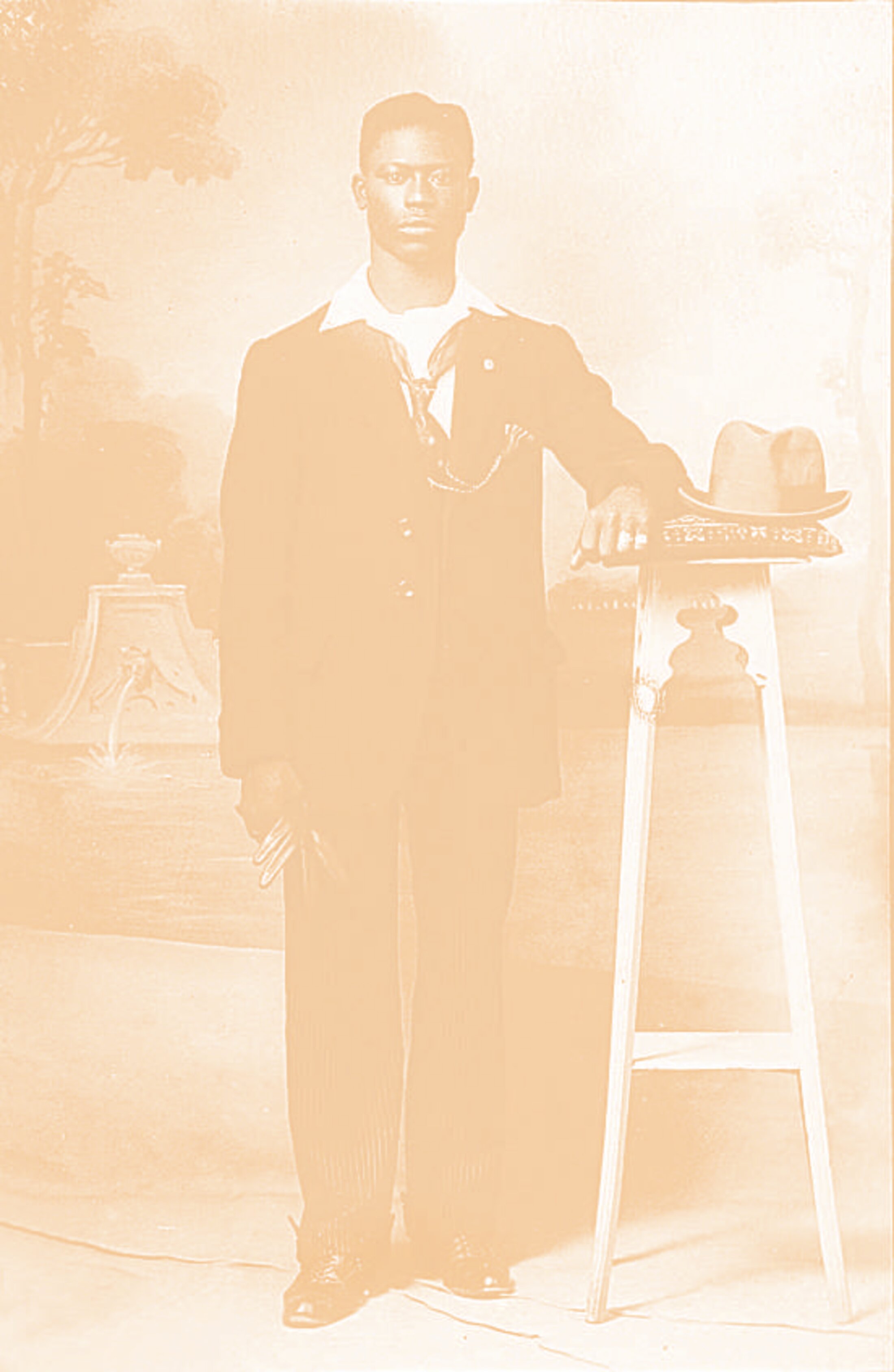

The contemporary view of the first African or Caribbean immigrants is based on society's image of immigrant populations who arrived in France much later, in the 1960s. This photo [right] is exceptional because it dates from before the First World War and gives us a completely different perspective.

It shows a worker, most likely a docker or a sailor, having his photo taken, with all the attributes of a posed studio photo - the smart suit, his hat placed on the stool next to him. It illustrates a certain level of success, and he will send it back to his home country or give it to his girlfriend in France.

There are a number of things in this photo which are fantastic because they give a very different picture of black people in France from the one in our collective unconscious. There is the simple fact of this black presence in the country - few people are aware that it existed before 1914, although black immigration in fact goes back a long time.

And there is a form of pride. Here we have someone who poses and symbolises the sort of social success to be expected from coming to work in France. So this photo breaks the usual rules, with all the usual expectations and with the chronology we have in the back of our minds.

Enlargement : Illustration 4

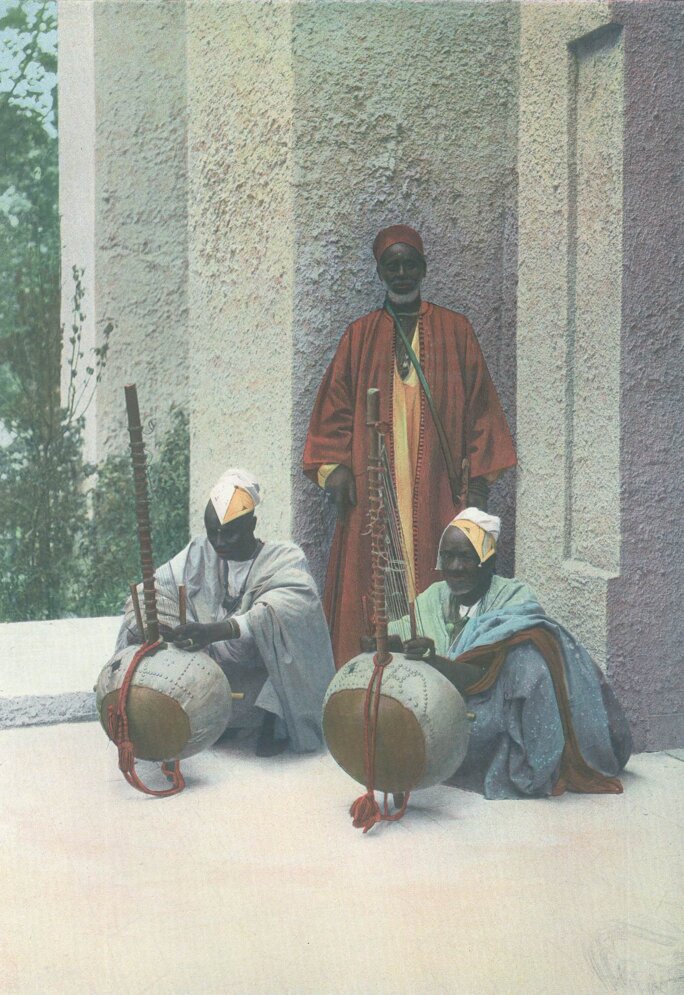

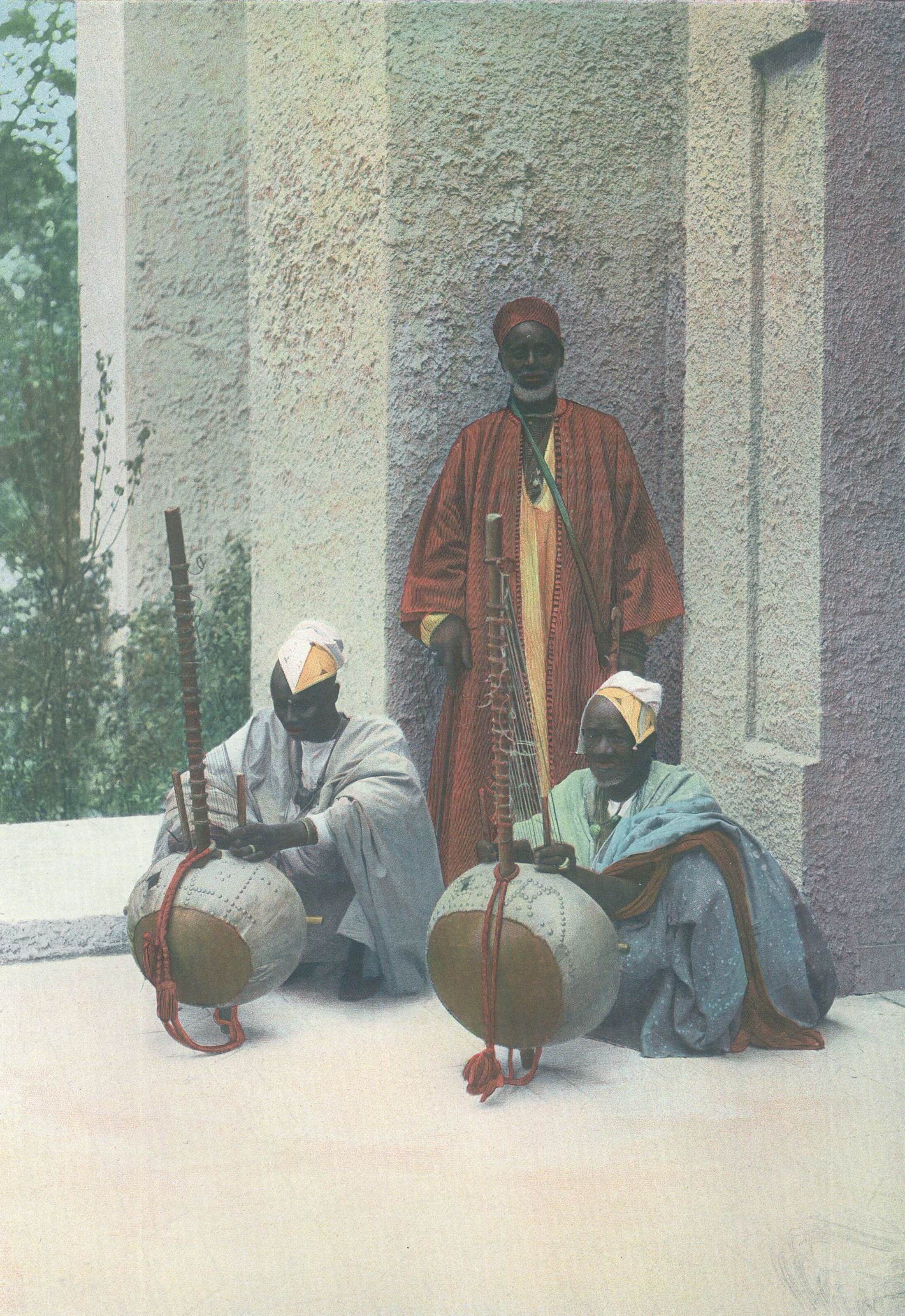

This photo from the World Fair in 1900 [left], however, is an utterly stereotypical image, claiming to be a model of a piece of Africa in the centre of Paris. At a time when very few West Indians or Africans lived in France, particularly from the elites, the World Fair was a major turning point as the new century began. It recreated the colonial empire in the very heart of Paris.

And French people who hardly knew anything about these peoples and their countries of origin - even though some could be seen in the Jardin d'Acclimatation - had these reconstituted colonial worlds before their very eyes and discovered them while strolling down the alleys at the Fair. In this way an uncontroversial image of a pacified empire was created in the popular imagination.

Of course, it was nothing but colonial theatre, but at the same time it allowed this totally European world to gain some familiarity with hitherto unknown Black worlds. French people know what a kora [a 21-stringed harp used in West Africa], or indeed a Muslim prayer, sounded like, and what Senegalese traditional dress looked like, because they saw it all at the World Fair, even if it was just as snapshots. Never before had so many people - 50 million in all - had access to anything like this.

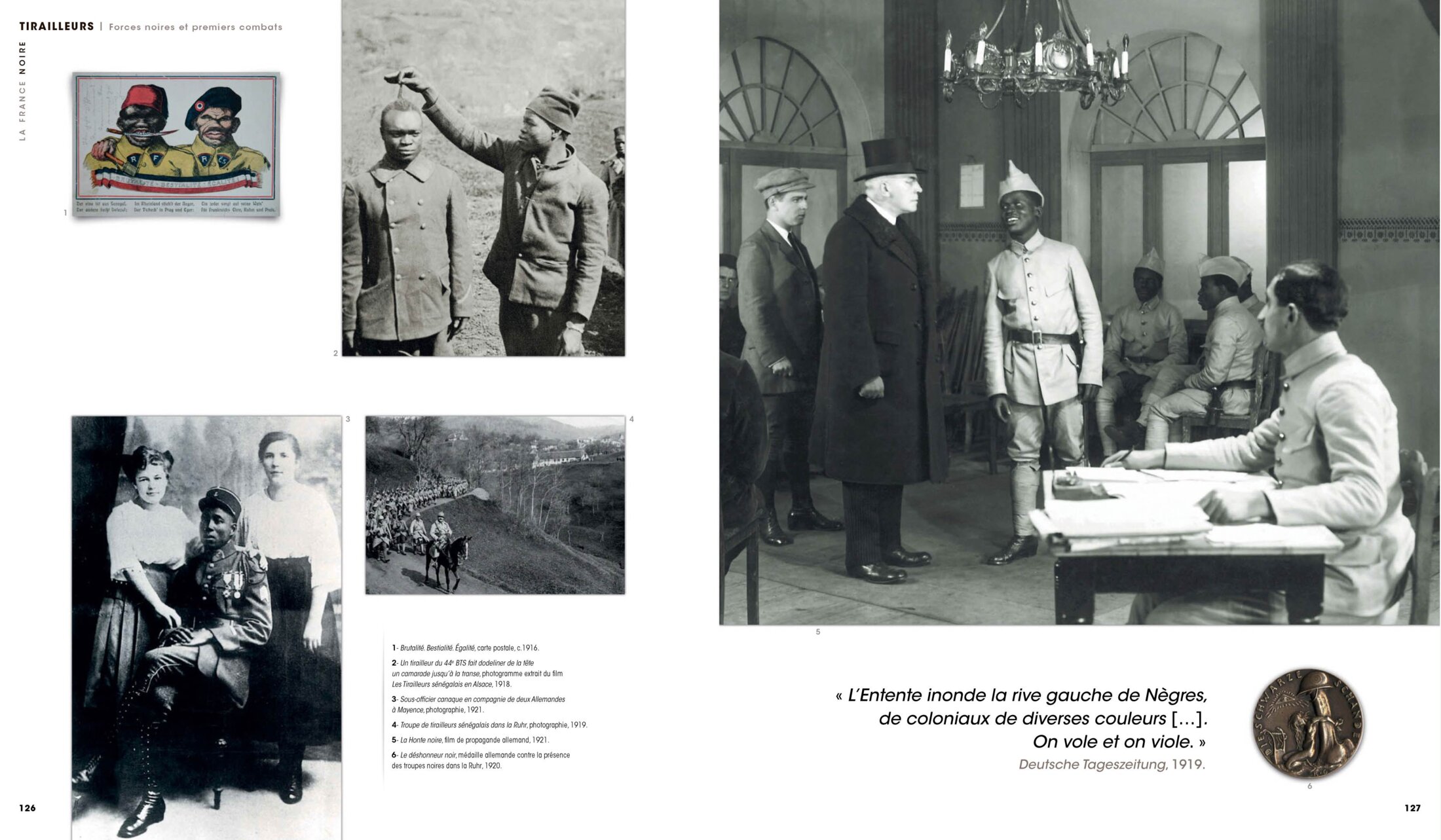

Germans invent 'black shame'

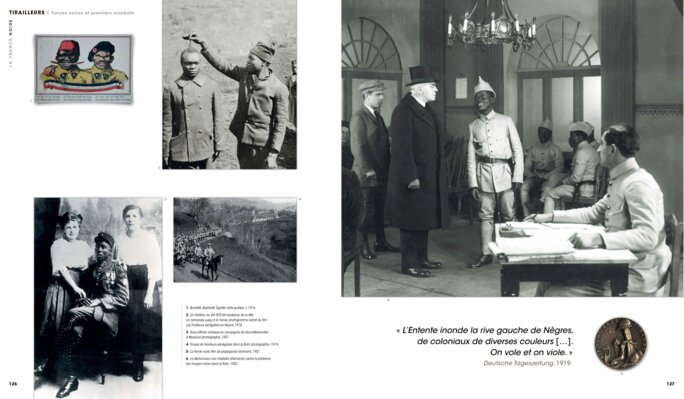

These photos (below) illustrate a little-known story. They illustrate a myth known as the "Black Shame", [translated from the German ‘die schwarze Schande'] which held that the French had employed Black troops, which in reality included North African regiments, to occupy parts of Germany after the First World War with the explicit aim of humiliating the defeated Germans. From 1919, German propaganda on this matter was very virulent.

Enlargement : Illustration 5

It even produced a film called The Black Shame which came out in 1921.The big photo on the right of this collage is an extract from it. The film is an incredible tale of black soldiers raping a young woman. In her humiliation she takes her case to the courts. The film ends with a call from Germans, aimed particularly at Americans, along the lines of: ‘you Americans, you understand, you outlaw mixed marriages and racial mixing, help us to save the German race'.

It is the same theme as can be seen on the medal at the bottom right dating from 1920, with a young German woman tied to an erect penis topped with a French military helmet. Hitler would take up the exactly same myth three years later when he wrote Mein Kampf, in which several pages relate the protests of German nationalists against the "Black Shame" imposed by the French.

It is a tenacious myth which would hold sway for a long time in popular consciousness. A reflection of this was how some German troops behaved in 1940 when black French soldiers were systematically massacred rather than being taken prisoner during the Battle of France. We have all forgotten that, in 1940, the German army made a slight detour to Reims and destroyed the monument to the Black Army of Reims during its march on Paris. This illustrates something of how the phenomenon was internalised and transmitted.

The other side of this coin is just as fascinating. Just after the First World War, France found itself in a very strange position. On the one hand it had to pay tribute to the valour of its black soldiers in the 1914-1918 war and condemn the racist attacks directed at them by German nationalist leagues and the German press. But on the other hand, it was in the process of refusing them French citizenship.

From exoticism to exclusion

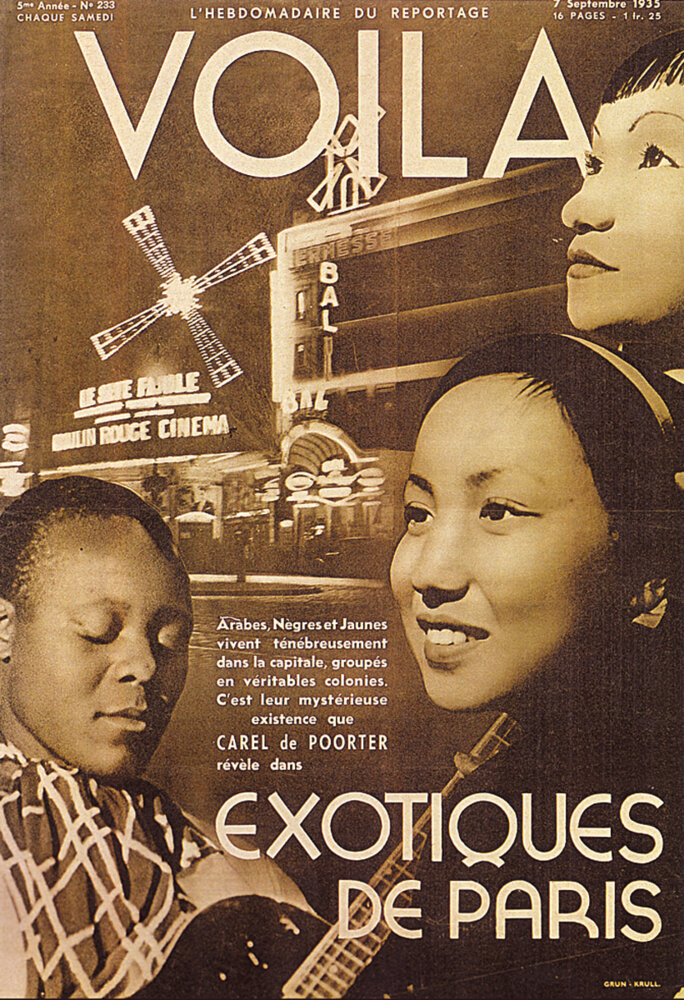

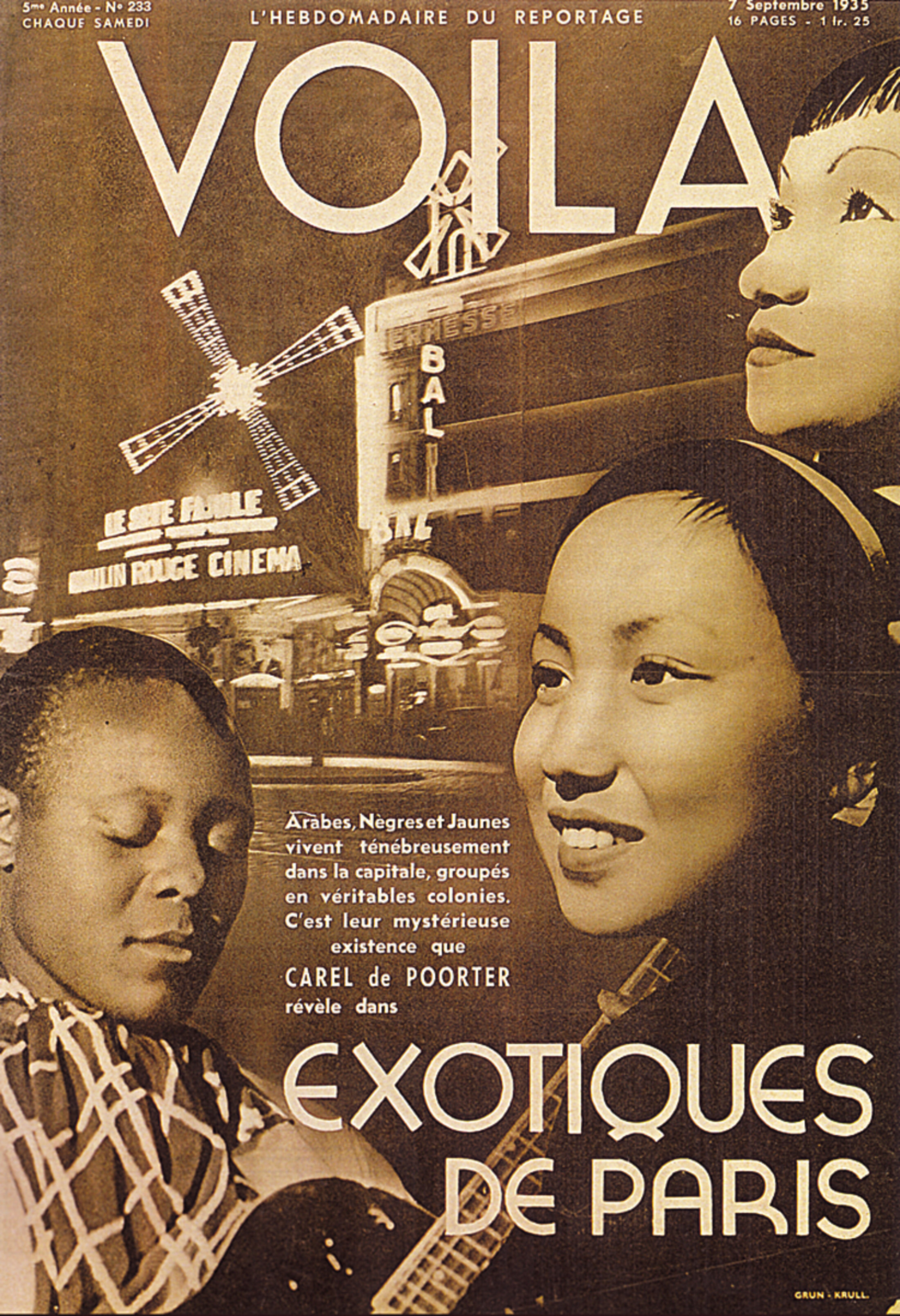

Enlargement : Illustration 6

This picture [right] is the cover of a 1935 issue of the magazine Voilà which reflects the prevailing ideology at the time. It focuses on the immigrant presence, particularly in Paris, but also everywhere in France, in Bordeaux or Marseille. When French people go out to buy a baguette, they no longer turn and stare if they see someone from overseas.

But what is interesting here is that all immigrant groups, from the Far East, North Africa as well as blacks, are taken together as the subject in the same edition of the magazine and are all classified as exotic. Inside, the report shows that "these people" live "here" as they would "over there". You would think you were in the streets of Bangkok or Dakar.

By classifying these different groups as exotic and as all the same as each other, it implies that they are not like us and that in some way, them being here is "abnormal" because structurally, they "do not come from here".

The fact that they are exotic implies that their presence is illegitimate. They are exotic people in our country who are therefore on the margins of what is normal, and what is normal is the white man.

Enlargement : Illustration 7

This photo [right] was taken of the 12th regiment of Senegalese riflemen which had come for the Bastille Day celebrations in 1939. It is a typical photo of the arrival of combat troops in wartime. It seems as if these men have arrived straight from Africa and that behind them are thousands upon thousands of troops from the colonies.

The persistence and frequency of such pictures of "troops of colour" marching past is astonishing. The history of the Great War is being re-written. For the 50th anniversary of independence in African countries, African troops were brought to march along the Champs Élysées. For the 14th July parade for the 1989 Bicentennial of the French Revolution, Jean-Paul Goude included riflemen in the procession.

I also think it is interesting to note how no one is looking at them, how the people around are looking rather at the camera. Black soldiers have already become part of the scenery.

Enlargement : Illustration 8

This picture [left] shows illegal immigrants occupying the Cité Nationale de l'Histoire de l'Immigration. For me this is a wonderful historical irony. The place was built in 1931 for the World Fair, to glorify colonial history. It became the Museum of the Colonies up to the 1960s, then the Museum of African and Oceanic Art, even though in this country there is no museum of colonial history. They preferred to have a museum of the history of immigration to avoid it becoming a museum of colonial history.

And, as a museum that has never been officially inaugurated by the French Republic, who should occupy it in 2010 but those with no official residence papers from that Republic. The whole thing has come full circle.

The occupation was its real inauguration. They placed their flag in front of the colonial frescos which adorn the museum walls. In the foreground, a poster demands official residence papers. I felt the issues of the whole century were concentrated there.

That is why we wanted the book to end with this particular photo. These illegal immigrants are a reminder that this place is linked to the history of immigration and colonisation. They are no longer passive onlookers but actors who take part actively. They take possession of history and of their own legitimacy in the process of history.

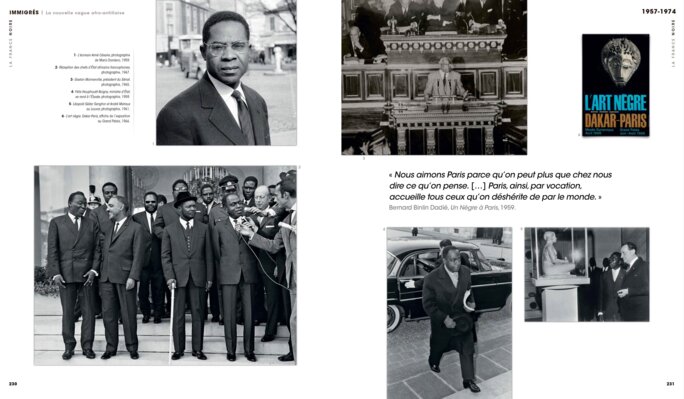

Blacks scarcer in politics than a century ago

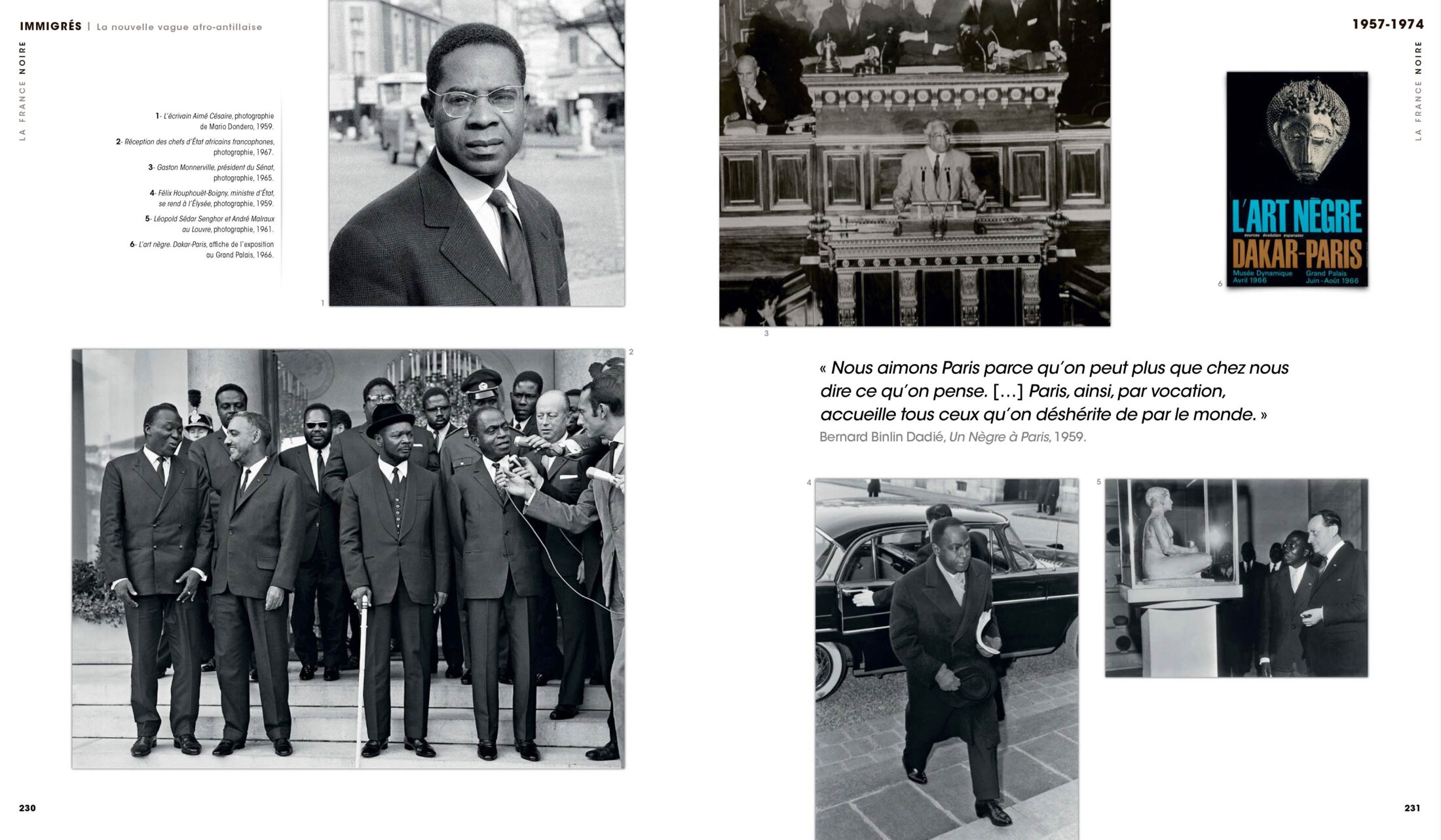

This double-page spread [below] from the book shows more or less everything France has forgotten about. There have been elected members of Parliament from Santo Dominico, the Antilles, Africa and Guyana since the French Revolution, with seats in both the Senate and the Assemblée Nationale [lower house of Parliament], and far more than there are today.

Some, like Gaston Monnerville, who was president of the Senate for over 10 years, managed to attain the highest levels of the Republic. Félix Houphouët-Boigny was a minister. Aimé Césaire was a Member of Parliament.

Enlargement : Illustration 9

And their predecessors have been forgotten even more. Over a century ago in 1904, following a difficult political struggle, Parliament elected a Black vice-president of the Chamber of Deputies. He was Gaston Gerville-Réache, the Member of Parliament for Guadeloupe.

We have also forgotten Members of Parliament like Hégésippe Légitimus, grandfather of [the contemporary actor and comedian] Pascal Légitimus, who was elected to the National Assembly in 1899. When he arrived in Paris, L'Assiette au Beurre, a visual satirical anarchist weekly, filled its 16 pages with caricatures of him portrayed as an Uncle Tom. He was nevertheless a Member of Parliament.

Would it be possible to have a black vice-president of Parliament nowadays? How can we explain the decline in black representation in politics compared with the last century? When we talk today about diversity in political life, we should remember that we have already known such diversity, and that we were one of the most advanced countries in the world in this respect.

And we have regressed. Looking over the long term allows us to understand that there have been ebbs and flows, and that the current generation is perhaps experiencing the biggest retreat in black political representation.

- La France noire, trois siècles de présence (‘Black France, a presence over three centuries') was published in November in France by Editions la Découverte, priced 59 euros.

-------------------------

English version: Sue Landau (with Graham Tearse)

(Editing by Graham Tearse)