Amélia, 14, is the youngest of Calixte Songa Mbappé's five children. Since her mother’s death four months ago, she spends her days lying on her bed, in silence, with just her mobile phone for some kind of distraction. “I leave at night to go to work and I leave her alone in the flat,” explained Aurelle Kedy, her elder sister, who is a nurse. “It worries me greatly to see her like that, with no words.”

Their 54-year-old mother, a care home worker, died on May 1st from Covid-19. Until then, Amélia and her brother Leonel, 22, a student, lived in the family home, a house in Villejuif, a southern suburb of Paris. Now they spend their time between Aurelle’s flat in the neighbouring suburb of Alfortville, and the home of their brother, Aristide Dissake, who lives in the south-west city of Bordeaux. Their other sister, Anrielle, lives in the United States, from where the 27-year-old followed the news of their mother’s hospitalisation and subsequent death, and who was unable to attend her funeral.

“The day before she died, I was ashamed and frightened, both at the same time,” recounted Aurelle, 29, speaking to Mediapart in her small flat. “Without either parent, what were we to become? What would people think of us? There was panic, also, in knowing that now we were orphans.”

Aurelle was speaking to Mediapart after working her overnight nursing shift in a hospital psychiatric service, her eyes creased with fatigue. For the past month she has been doing temping work, seven days a week, and preferably night-time shifts because it pays more than daytime assignments. Before she started the job in the hospital, she had been part of team testing passengers for novel coronavirus infection at the Orly airport. “I don’t know what we’ll do for my little sister at the rentrée [after the summer holiday period], so I prefer to work as much as possible to put some money aside,” she said.

During the spring, when the coronavirus epidemic was sweeping France, she finished her training as a nurse, after which she was requisitioned to work as an auxiliary nurse in the intensive care unit and cardiology service of the major Paris Pitié-Salpêtrière hospital which was, like others in the city, overwhelmed since early March with arrivals of patients with Covid-19. Living on a tight budget, she alternated between days and nights, also working weekends and on public holidays. It was during that intensive time that her mother became ill.

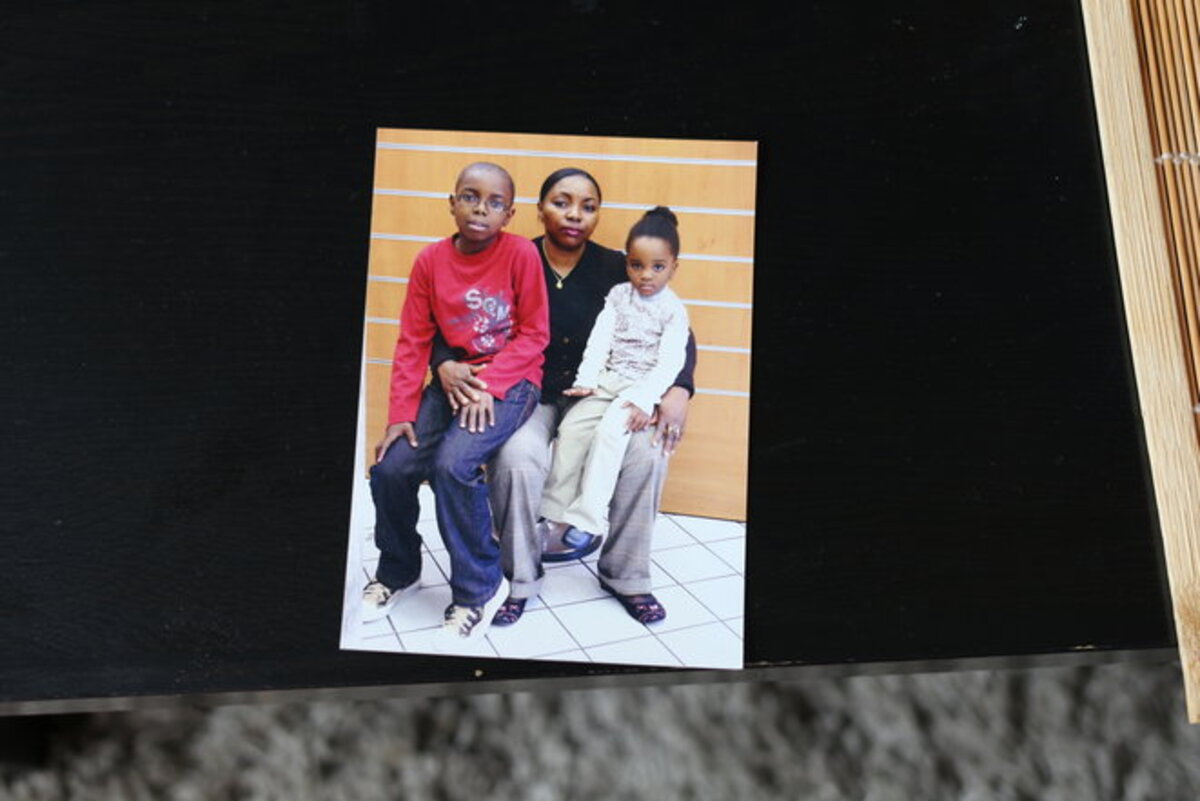

Born in Cameroon in west-central Africa, Calixte Songa Mbappé arrived in France in 2004. A single mother (the father of her children has been absent from their lives for many years), her two main interests were her family and her work, followed by the joy she found in tending her garden and flowers, and her cooking, which she delighted in. Aurelle recalled how her mother was highly sensitive to the plight of others, to the homeless and the vulnerable. “Sometimes, she would cry at home when the elderly people she looked after had passed away,” she said. “I found that a bit exaggerated, but I said nothing.”

Calixte worked her last months on short-term contracts at the Cousin-de-Méricourt care home, managed by Paris City Hall and situated in Cachan, another Paris suburb that sits close to the family home in Villejuif. Her working contract officially described her post as a “hospital service agent”, which in reality means carrying out cleaning tasks, but she became increasingly involved in washing the residents, moving from one room to another. Despite her own health problems, she was initially given no personal protective equipment (PPE) of any kind. The protective face masks finally became available to staff at the care home just as France went into a two-month public lockdown in mid-March. But the novel coronavirus had already entered the establishment several days earlier.

“Well before she became ill, my mother spoke of it,” said her son Aristide, 32. “We used to laugh – ‘Corona, corona, always the corona’ – without knowing that it would affect us. I think that because she still had children to look after, bills to pay, and no stable work contract, she felt she had to work. That is what drives me mad today, the fact that she should have stopped [work], if she hadn’t been afraid of losing her job.”

Enlargement : Illustration 1

It was on March 16th, the same day that President Emmanuel Macron would make a televised address to the nation in the evening to announce the immediate lockdown, when Calixte complained of feeling a little unwell. On March 18th she visited a doctor who thought she was suffering from rhinopharyngitis, a sore throat, although she had begun coughing to the point of complaining of pains to her chest.

One week later, after she had endured a particularly difficult night, Aurelle – alerted to the situation by her young sister who was living with their mother – called the fire brigade, which in France doubles as a first-stage emergency medical service. They refused to intervene. Aurelle then drove her mother to hospital. “After a hundred metres on foot to reach the Accident and Emergency desk, her oxygen level had fallen steeply,” recalled Aurelle. Calixte was immediately hospitalised, intubated (her daughter remembered that she had previously been “scared stiff” at the idea) and placed in intensive care. Very quickly she was diagnosed as suffering from Covid-19.

It was the beginning of a nightmare situation for her and her family. Across Paris, the hospitals were swamped with Covid-19 arrivals. Available beds had become scarce. After Calixte’s condition was considered stable by the hospital doctors she was transferred, unconscious, to a less busy hospital in the Normandy town of Caen, about 220 kilometres north-west of the capital.

Over the following three weeks, Aurelle was able to visit her mother on three occasions. The rest of the time she kept contact with the hospital doctors by phone, acting as an intermediary with her brothers and sisters.

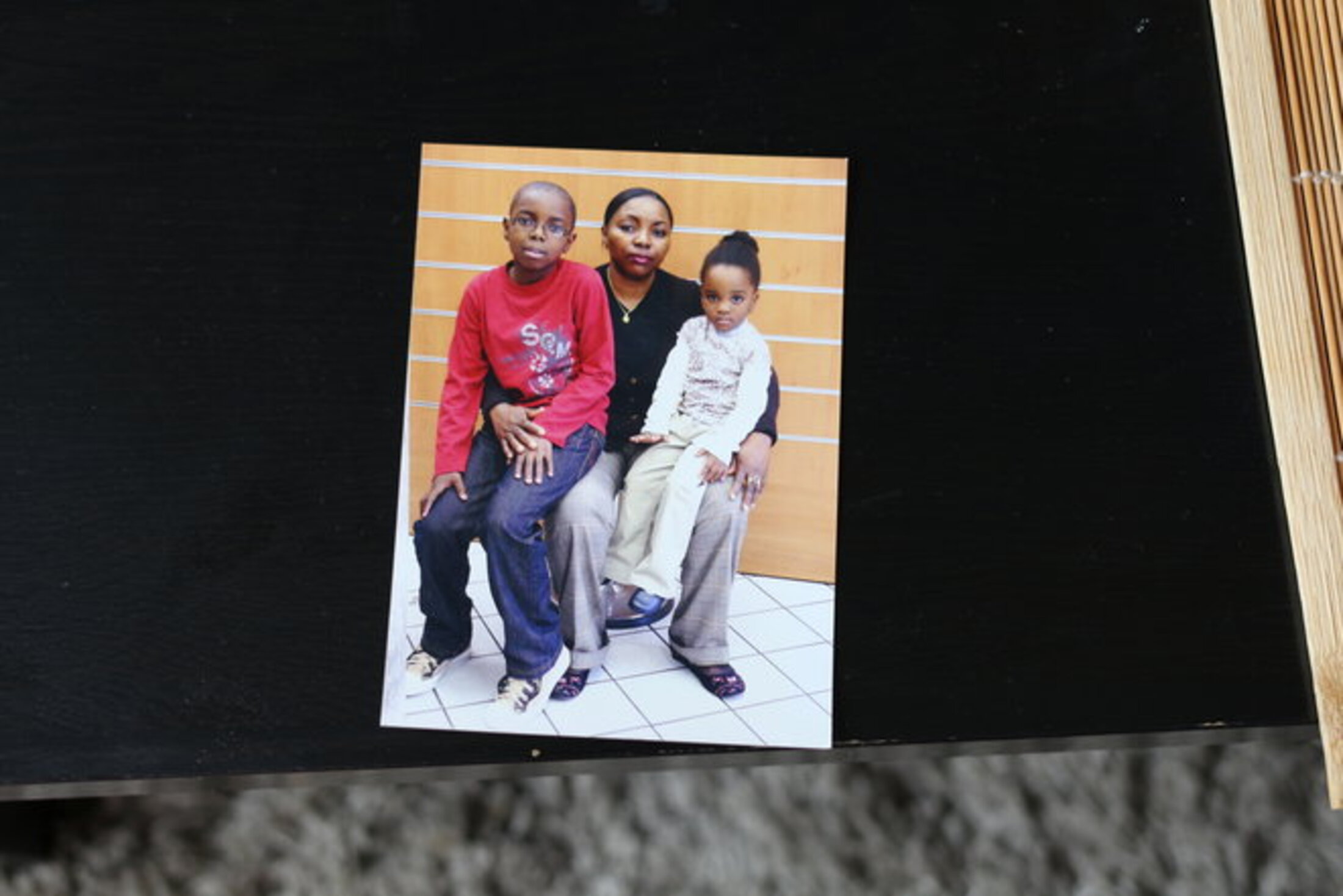

Enlargement : Illustration 2

Meanwhile, her mother was slowly slipping away. “They didn’t listen to us, couldn’t care less about our opinion,” said Aurelle. “We had contradictory information according to whom we spoke to. It was inhuman. For them, it was a therapeutic failure and they insisted that we [agree to] disconnect her.”

Calixte finally died of a heart attack. “In the company of a nurse and auxiliary nurse,” the young woman added. She and her siblings have asked to see her medical file, so far in vain.

Their grief was soon joined by anger at the thought that Calixte’s fate might have been avoidable. “My mother worked without a mask, the nursing manager having considered that they were not necessary,” said Aurelle. In a medical report sent to the social security services with the aim of establishing Calixte’s death as having been caused by an occupational disease – caught at the workplace – it was noted that the history of the case included a “cough and fever […] in a context of working without protection in a care home”.

One of Calixte’s colleagues, whose name is withheld, told Mediapart: “We were in despair January, February, March. We requested masks, but the nursing managers, like the doctor, told us that there was no need to be afraid.” Amid the concerns of staff, most of those at the care home who were on permanent working contracts took sick leave. Those who were left on the frontline were those without public employee status, or on short-term contracts like Calixte. “In the care home wing where she worked, it was absolute carnage, numerous residents died, and nearly all of us were contaminated,” said the woman colleague.

On July 28th, the siblings filed an official complaint against their mother’s employer, Paris City Hall, for “placing in danger the life of others leading to death and failure to meet legal requirements”. Contacted on several occasions by Mediapart, Paris City Hall did not reply to questions submitted to it.

'Do we speak enough about those who passed away?'

In parallel to their emotional distress, the siblings also faced dire financial problems. During their mother’s hospitalisation in Caen, they had to request emergency financial aid for food from the welfare system. Two weeks after submitting their request, they were given a grant of 300 euros. While Aurelle angrily described that as “like alms”, her brother Aristide, who took charge of applying for aid, was less severe, arguing that Paris City Hall did support them, to the point of paying outstanding rent following the death of their mother, its former employee.

Calixte’s children decided they could not afford to repatriate their mother’s body to her native Cameroon, where their grandmother lives. Instead, she was buried in the Paris region. The cost of the funeral arrangements was 6,500 euros. The management of the care home where Calixte worked initially accepted to pay a third of the sum, but a former colleague at the establishment, a member of the militant CGT union, convinced them to pay the cost in full. “Because she was on a temporary contract, she didn’t have the right to a company death benefit scheme and so it was the only thing that they considered necessary,” said Aristide.

Enlargement : Illustration 3

As for the future, Aurelle for now faces a gruelling work schedule to make ends meet. Her youngest brother Leonel initially planned to further his studies with a degree course with the hope of embarking on a career in business, but this month he decided to apply for a job in public administration, which offers a more stable and certain situation. As for Aristide: “I have children, a job, I’m the eldest, I have to be strong. But I do sometimes wobble.”

The elder siblings have asked for public aid for the two youngest, Amélia and Leonel. “That seems to me important,” said the latter. “Our life has been turned upside down, we were totally taken by surprise. Apart from the financial aspect, it is psychologically important, for me, for the other families of victims, to be recognised.”

In 1917, towards the end of WWI, France introduced a protective status granted to the orphans of soldiers killed in battle. The children were made “pupilles de la Nation”, which has over the years since been extended to other categories, such as the children of police officers or magistrates killed in the exercise of their duties, and also the children of victims of terrorism. Without removing the rights of guardianship by families, its provisions include financial aid, help in furthering the children’s education, and favouring their access to employment in the public sector. Amid the toll of deaths this year among frontline healthcare workers during the coronavirus epidemic, there were a number of calls for their children to be granted “Pupille de la nation” status. On May 26th, a motion calling for such a move was put before the National Assembly, the lower house, by members of President Emmanuel Macron’s ruling LREM party, and was unanimously approved.

“These children must be able to continue to live, at least on a material level, as if their parents were still here, to continue their studies as serenely as possible,” said Patrick Chamboredon, president of the council of the French nursing profession’s national ethical and advisory body, the Ordre des infirmiers, which supports the move. “It is also a duty of remembrance. What motivated us is what was said by the French president, telling us that a war was declared. If it is war, then it is now necessary to take care of the collateral victims.”

Until now, no official records have been completed of precisely how many healthcare workers have died from Covid-19, nor the numbers who were contaminated by the virus, although some figures available earlier in the year show that these amount to at least several thousands. Doctors’ associations estimate that more than 40 general practitioners alone died from the disease. In late April, Mediapart compiled a non-exhaustive list of 37 cases of healthcare workers who succumbed to Covid-19 (in French, here).

The LREM party Members of Parliament (MPs) who were behind the parliamentary motion in May have said the project is now in the hands of President Macron. LREM MP François Jolivet said that, officially, the junior health minister in charge of child and family affairs, Adrien Taquet, is due to lead a study of the issue beginning this month. There is, however, no certainty of the outcome, and Taquet's office did not reply to questions submitted by Mediapart.

Meanwhile, Calixte Songa Mbappé’s children are hoping that Paris City Hall will include them in its own protection scheme of “pupilles de l’administration” which applies to the orphans of its employees. But for that, her death must be officially recognised as the result of her being infected with the virus at the workplace. Questioned by Mediapart, the health insurance branch of the French social security administration said the legal criteria defining when serious cases of Covid-19 can be considered to be an occupational disease have not yet been finalised.

This summer, the five siblings received an unexpected opportunity to raise their case at the highest level. This was an invitation to the traditional annual garden party at the Élysée Palace held on the eve of the July 14th Bastille Day celebrations, which this year was marked by a tribute to the medical staff who battled the epidemic. Aristide, Leonel and Aurelle were put up in a hotel in the west of the capital, from where they were bussed to the presidential office with other families of healthcare workers who fell victim to Covid-19. “The minister of health gave a thirty-minute speech in the garden, but we arrived too late, and we were unable to speak with anyone,” complained Aurelle. “What did they think, that we had come to drink apple juice and eat a petit four?”

The youngest of the five decided not to attend the presidential tribune to watch the military parade the next day along the Champs-Élysées avenue, which a number of families had been invited to. Aristide however did attend – “alone, with the emotion of living that,” he explained, “and to have the president who came around [us], all the same”. At the end of the ceremony, Emmanuel Macron, his wife Brigitte and health minister Olivier Véran spent a few minutes meeting with the families present. Aristide spoke with the minister. “I asked him for my [young] brother and sister, about the status of ‘pupille’,” he said. “But at the time, I didn’t think of asking all my necessary questions.” Macron confirmed the project to award “pupille de la Nation” status to the orphaned children of health workers, but gave no further details.

The French president, who has spoken in public about the epidemic on numerous occasions, has said little about the deceased, save for a post-lockdown televised address on June 14th, when he announced the agenda for the remaining gradual return to public activity. “And I want to think tonight, with emotion, about our dead, their families whose grieving was made all the more cruel because of the constraints of this period,” he said.

To highlight the tragedy of the numbers of deaths from Covid-19 in turn raises questions over the long period of mask shortages, the contradictory statements throughout the spring on the strategy in face of the epidemic, the delay in recognising the surge of Covid-19 in care homes, and the degraded state of France’s public hospital system.

“Why didn’t they listen to us when we asked for masks?” commented the care home colleague of Calixte cited earlier. “For me, its death from negligence,” she added.

“We often hear it said that numerous deaths were avoided,” said Aurelle. “But do we speak enough about those who passed away? Thirty-one thousand deaths, all the same, and as many families. It’s not nothing.”

Aware of the fragile nature of her professional situation, Calixte Songa Mbappé, who had already obtained the qualification of professional carer, was planning to train to become a qualified auxiliary nurse, which would have allowed her stable employment. Her daughter Aurelle, who has only just recently become a qualified nurse, is now thinking of leaving the profession. “The death of my mother, the way the institution has used – sometimes mistreated – us throughout the [health] crisis, that has in a way disgusted me.”

-------------------------

- The original French version of this report can be found here.

English version by Graham Tearse