"The understanding of what represented virility in the 19th Century has become difficult, even impossible, notably to the eyes of the young," reads the introduction to the second volume of Histoire de la virilité (‘The History of Virility'), one of three editions totalling 1,500 pages and which were published in France in October.

Enlargement : Illustration 1

"How, at present, can one imagine that so many men agreed to suffer and die for the homeland," the authors ask, "[...] that so many men looked death in the face during duels, wanted to exercise a domination over peoples who they considered to be inferior, demonstrated a spirit of conquest, and who displayed a vigour during lovemaking, unconcernedly, that deprived the woman of certain erotic refinements?"

The History of Virility is a collective work, directed by French historians Alain Corbin, Jean-Jacques Courtine and Georges Vigarello. The three volumes focus on separate periods of history, beginning with Ancient times. This encyclopedia-like work, rich in text and illustrations, makes a distinction between the notion of virility and that of masculinity.

"Masculinity refers to the history of gender, begun some thirty years ago," says Alain Corbin, "and I'm always very afraid of psychological anachronisms. Virility is not synonymous with masculinity and it is not defined only in opposition to femininity. In the 19th Century, being ‘masculine' was more a question of grammar [1]. I prefer to put myself in the place of those that lived in an epoch, to get into their skin. And even today, for the rugby cup finals, for example, the talk was of 'virile' exchanges not 'masculine' ones."

For Georges Vigarello, the decision to devote 1,500 pages to virility is justified because "the notion has been little studied and it is currently the subject of questions, criticisms and problems that require going back in time in order to historicise it".

Enlargement : Illustration 2

But also, says Vigarello, because it provides a more original and complex perspective than a simple story about men. "Virility is considered the top male attribute, but it can be embodied by women," he explains. "In fact, we wanted to put Sharon Stone on the cover of Volume III. We didn't do it because of copyright issues. But we recently heard a reputedly strong woman reproach a man for being too soft [2]. The history of virility thus complicates relations between the sexes as well as the history of the masculine and the feminine."

The three editors of the book decided to cut this history of virility into three unequal parts. Volume I, The Invention of Virility, takes us from Antiquity to the Enlightenment. It shows how what it calls the "virile model" evolved over the ages, "without ever losing its benchmark of vigour and domination," though there are many gaps. There is the Christian universe, where homosexuality is condemned, then the medieval world, "where bloodshed gains the highest value as an indicator of character and strength". Later comes the modernist period, when "presence overrides a previous harshness and levity overrides the heavy hand of the past". As for the culture of the Enlightenment, it rocked traditional virility to its core due to a "new vision of power".

Volume II, The Triumph of Virility, covers the 19th Century, a time when the notion of virility had the maximum hold, when "the vision, the values and the standards that compose it are imposed with such force" that virility structures the vision of the world and of society.

The last volume, entitled Virility in Crisis?, is devoted to the 20th Century, after World War I with its human devastation undermined "the virile soldier myth and included masculine vulnerabilities into the culture of feelings". This first crisis was accentuated by "workers being dispossessed by machines; disqualified through unemployment," at a time when virility was confronted "by a challenge to its most ancient privilege by the awakening and the progress of gender equality and advances in feminism".

On the following pages, five authors who contributed to this monumental work decipher for Mediapart, through nine images, the evolution of the representation of virility.

-------------------------

1: In French and other languages, all objects are either masculine or feminine and this is reflected in the grammar. Interestingly, the noun 'virilité' is feminine in French.

2: During the Socialist Party primary in October, candidate Martine Aubry railed fellow candidate François Hollande for being too soft. Hollande won the primary.

Georges Vigarello:

Enlargement : Illustration 4

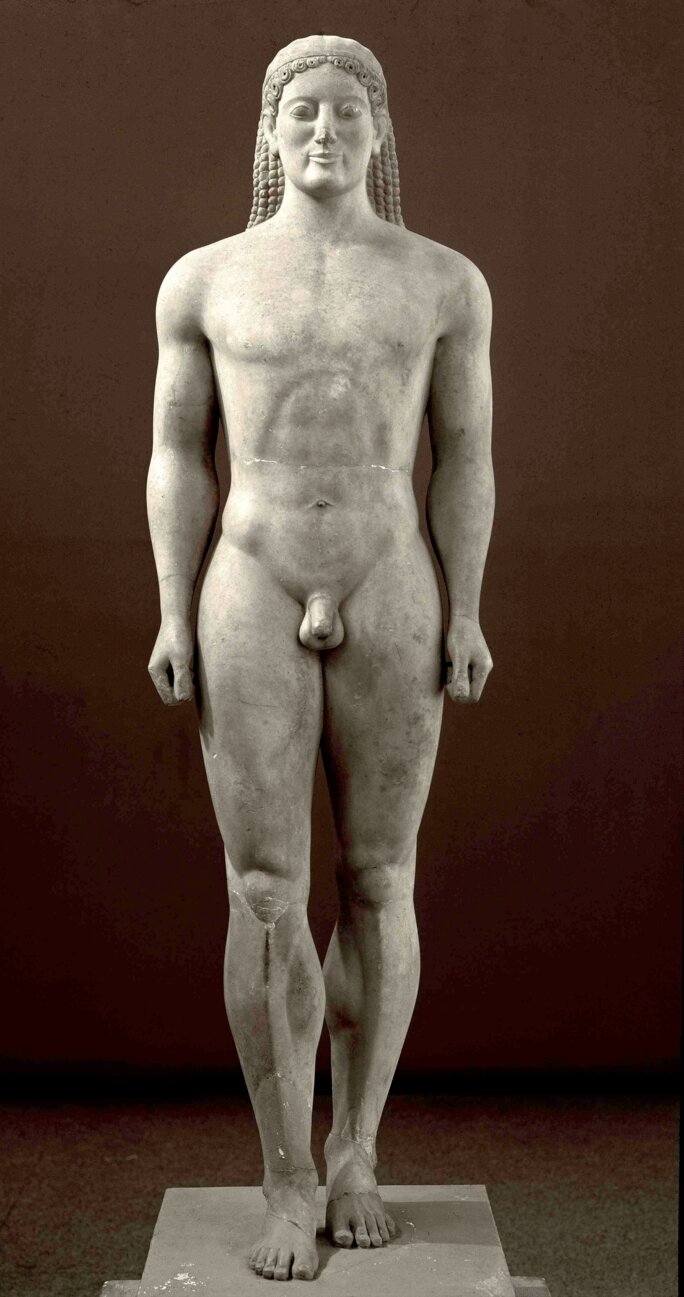

"This image of a Greek 'kouros', dating from the 6th Century BC, is an archaic, primitive young man, preceding the period of Greek sculpture incarnated by Phidias.

For the first time in the representation of ancient man, the curves are present and the body has volume and imposes that volume. But this work is very hieratic. It doesn't favour movement, it remains relatively impersonal.

Man begins to impose himself, but in a quasi-symbolic and abstract fashion where his strength is already felt but not yet as present as it will be in the sculpture of Phidias or of the Romans."

Enlargement : Illustration 5

Georges Vigarello:

"In this painting by Crispijn de Passe the Elder, entitled Virilitas Honori, what is fascinating is that it is the woman who is crowning virility but also that virility no longer has anything to do with muscular domination or a hieratic stance, as during Antiquity, nor with a domination founded on chivalry, bloodshed and swords as in the Middle Ages.

Man in the 16th century is capable of wearing the attributes of refined and delicate living including lace, ruff collars and needle-worked fabrics.

He is a courtier, as indicated by the castle in the background and his fingering of the treasure in the foreground. The courtier is able to combine delicacy and skill while at the same time affirming his masculine presence. This is a source of conflict with the old barons who cling to the values of chivalry and of men in armour."

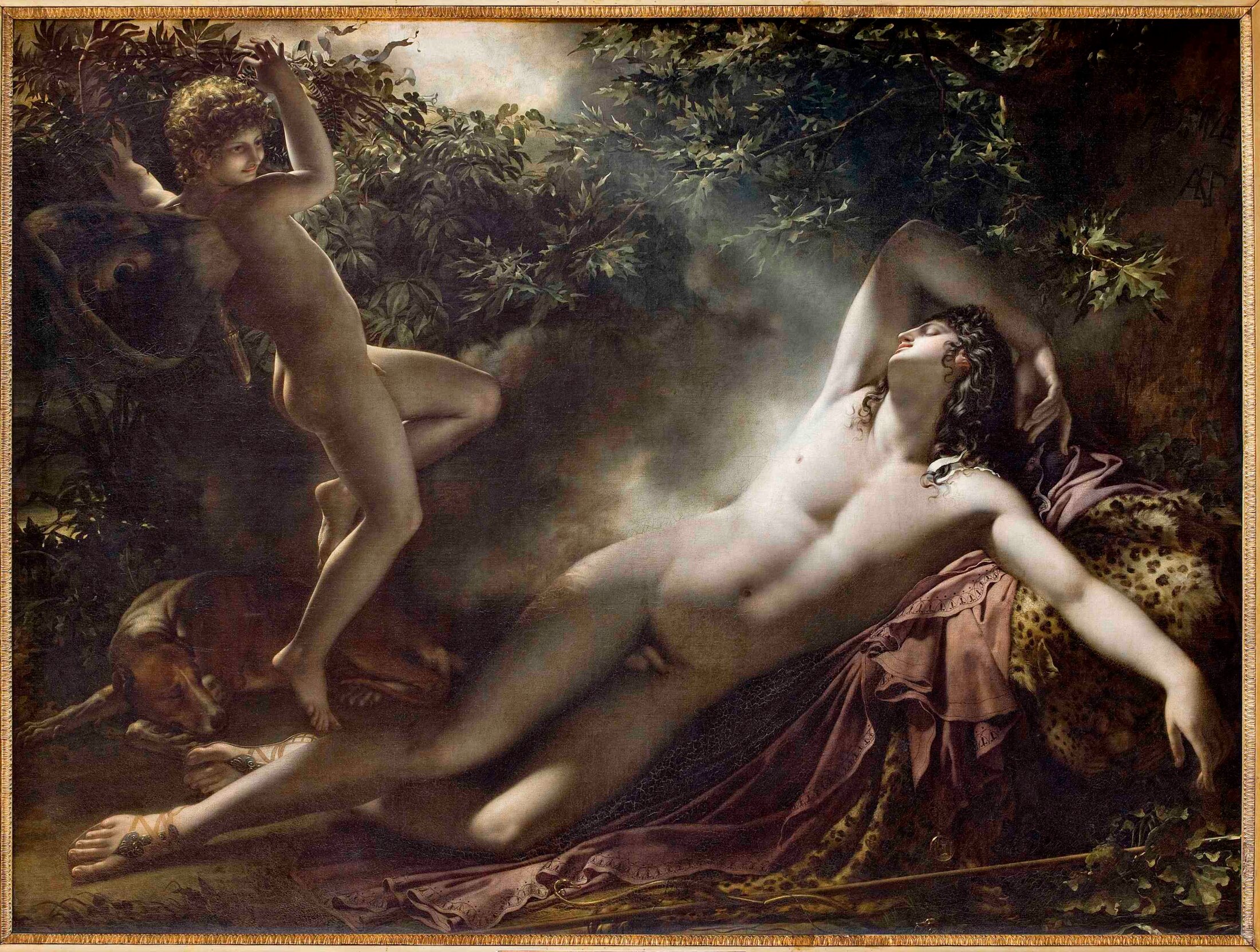

Enlargement : Illustration 6

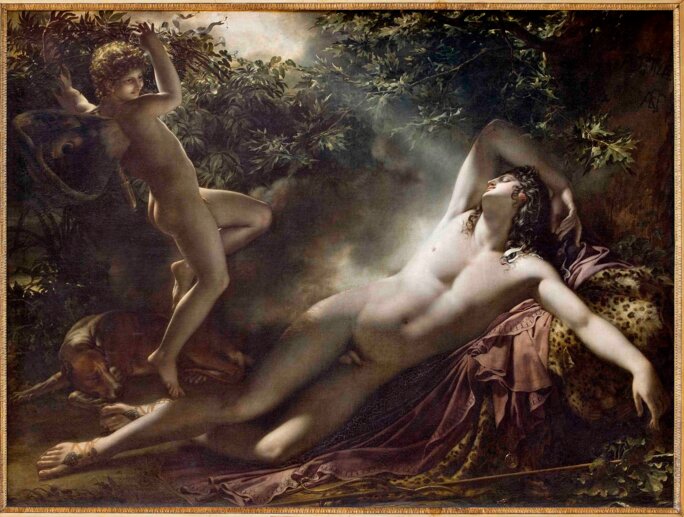

Arlette Farge:

"This painting by Anne-Louis Girodet, entitled The Sleep of Endymion, dates from 1791, therefore, in the midst of the revolutionary period. What strikes me here, with this androgynous character, is a sort of angst about who is man and who is woman. It is a man, but with long hair, with a feminine languor and ecstasy, thus an image which is very far from the aristocratic code of virility. This is the culmination of the Age of Enlightenment and of the concerns about virility raised by the questioning of absolute power.

The angel is also interesting, because it looks like the body of a large child, but not of a teenager. At that time teenagers did not exist. Even the word did not exist. It is an undefined body, somewhere between child and adult, between man and woman, as they were represented before the 19th Century imposed rigid codes for bodies and roles. It is only later that the bodies of teenagers were trained and tamed, even if this painting, which values uncertainty, is perhaps showing an ideology that is too pure to be true."

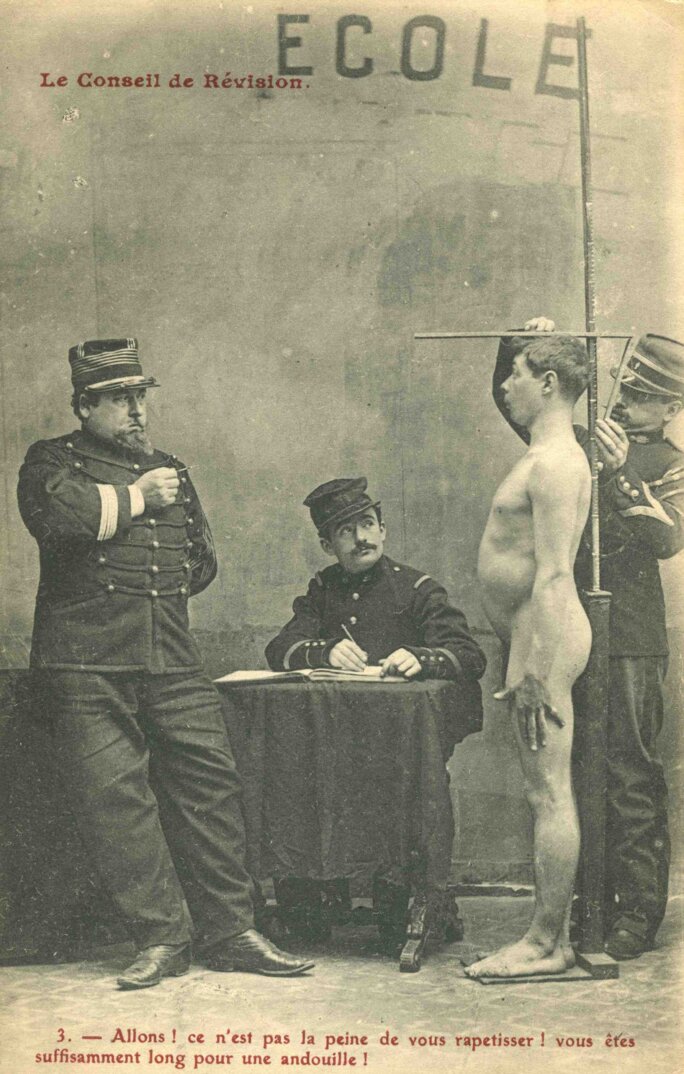

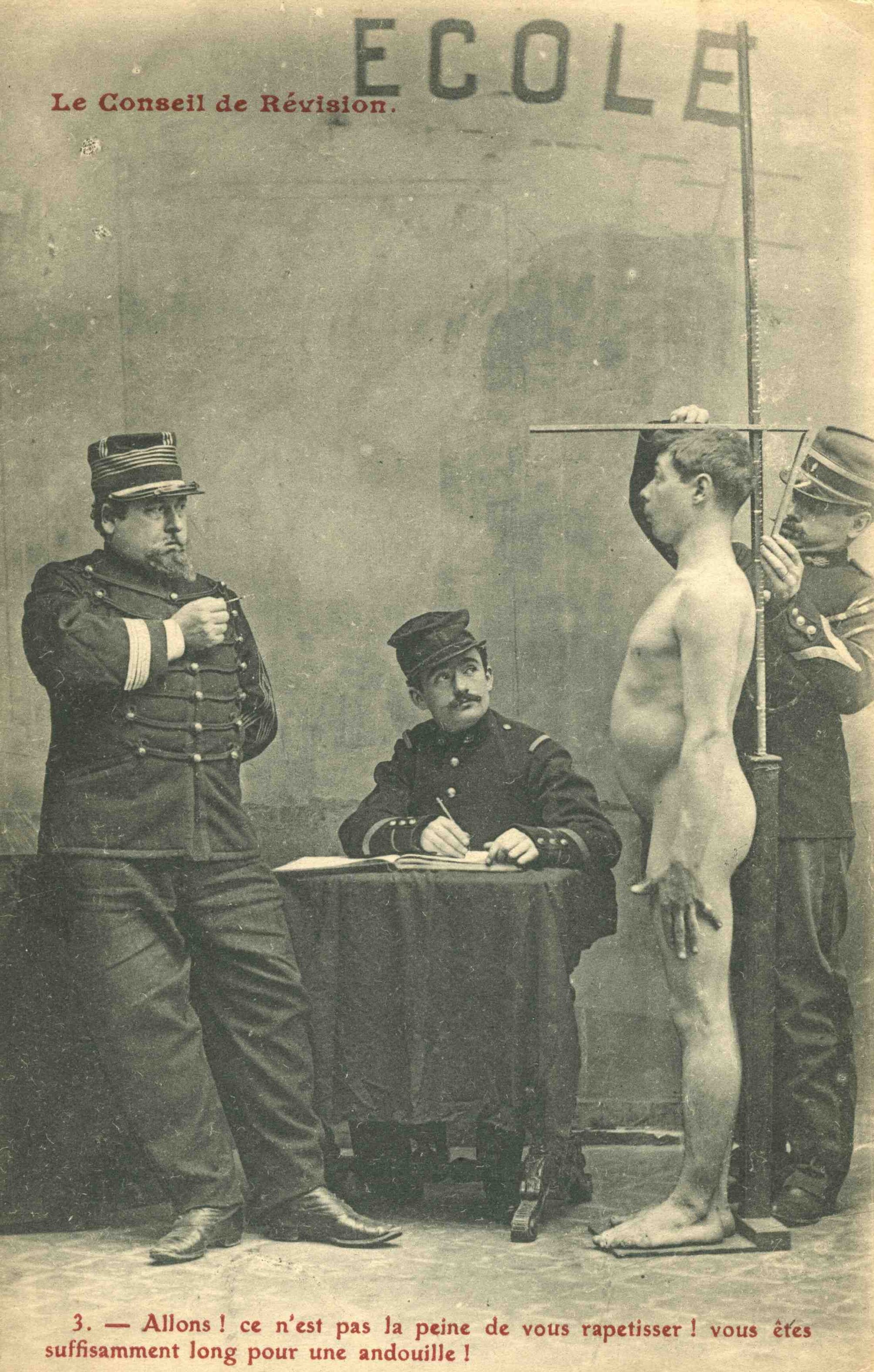

Alain Corbin:

Enlargement : Illustration 7

"I've personally had the experience of standing stark naked in front of the military doctor. That's quite something. At the time, to be ‘fit for service', also meant ‘fit for women'. Thus the army delivered a real certificate of virility. In the 19th century, all the boys faced the measuring board, and if you failed to measure up you were sent home, head hanging.

In the 19th century, courage, readiness to die for your country, the quest for glory, the necessity of taking up every challenge, were all imposed on men in such a way that virility wasn't merely an individual virtue, but something that ordered and permeated the whole of the society it underpinned."

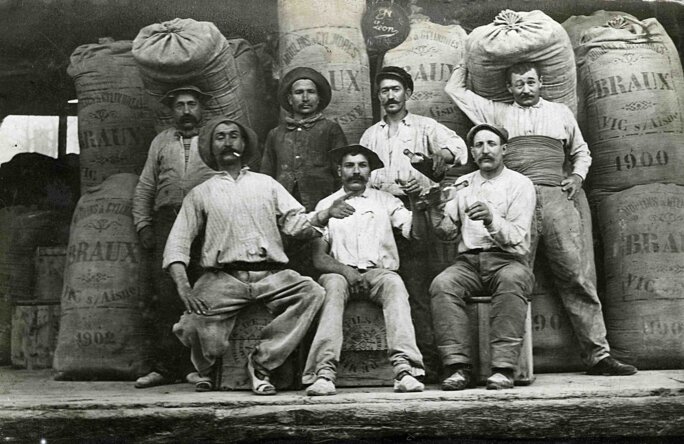

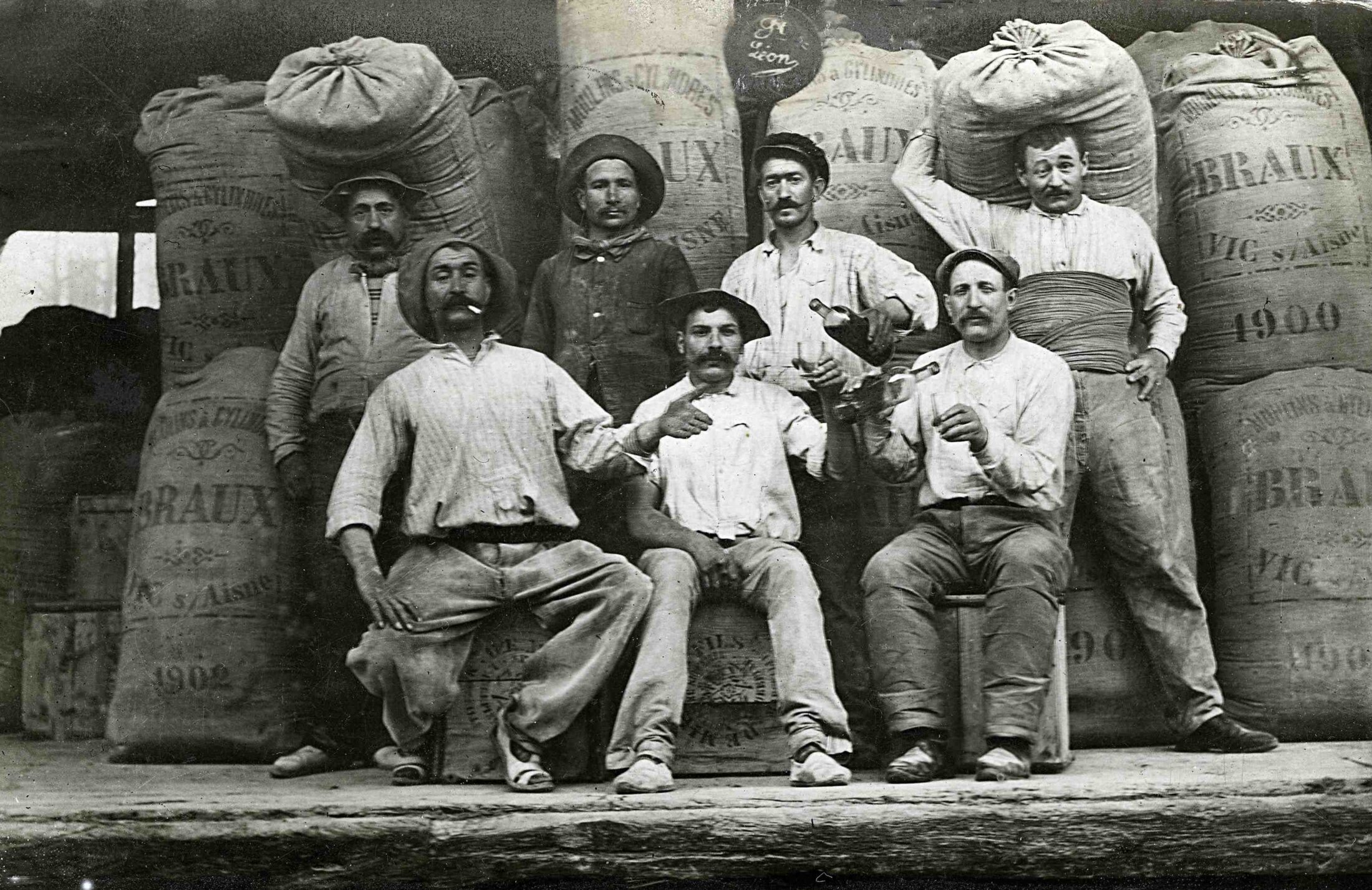

Enlargement : Illustration 8

Alain Corbin:

"The triumph of virility in the 19th century also resides in the multiplication of places where men gathered: school, boarding school, drill hall, smoking room, workplace. These are all so many theatres for the inculcation and development of traits defining the virile man.

In these worlds, the rookie in the barracks or the young man freshly arrived in the world of work has to find his place. The glassblower has to burn himself, the young bricklayer from the Limousin has to prove he's tough.

In this picture of [market porters at] the Forts des Halles from the very beginning of the 20th century, workers' social integration is manifest in body hair, the moustache, and attitudes that express might and muscle, but more in the spirit of the bon vivant, the man who enjoys the good things in life, than in the bodybuilders we see a century later.

One also senses in this image a way of flaunting pride in a savoir-faire, which would later be discredited, at the same time as a certain representation of working-class virility, with the arrival of machines and the economic crisis of the 1930s."

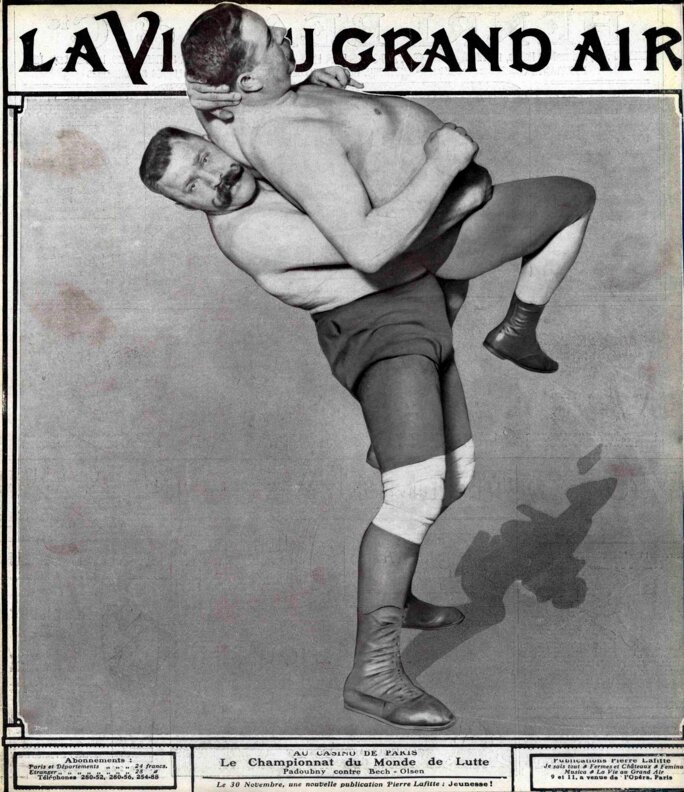

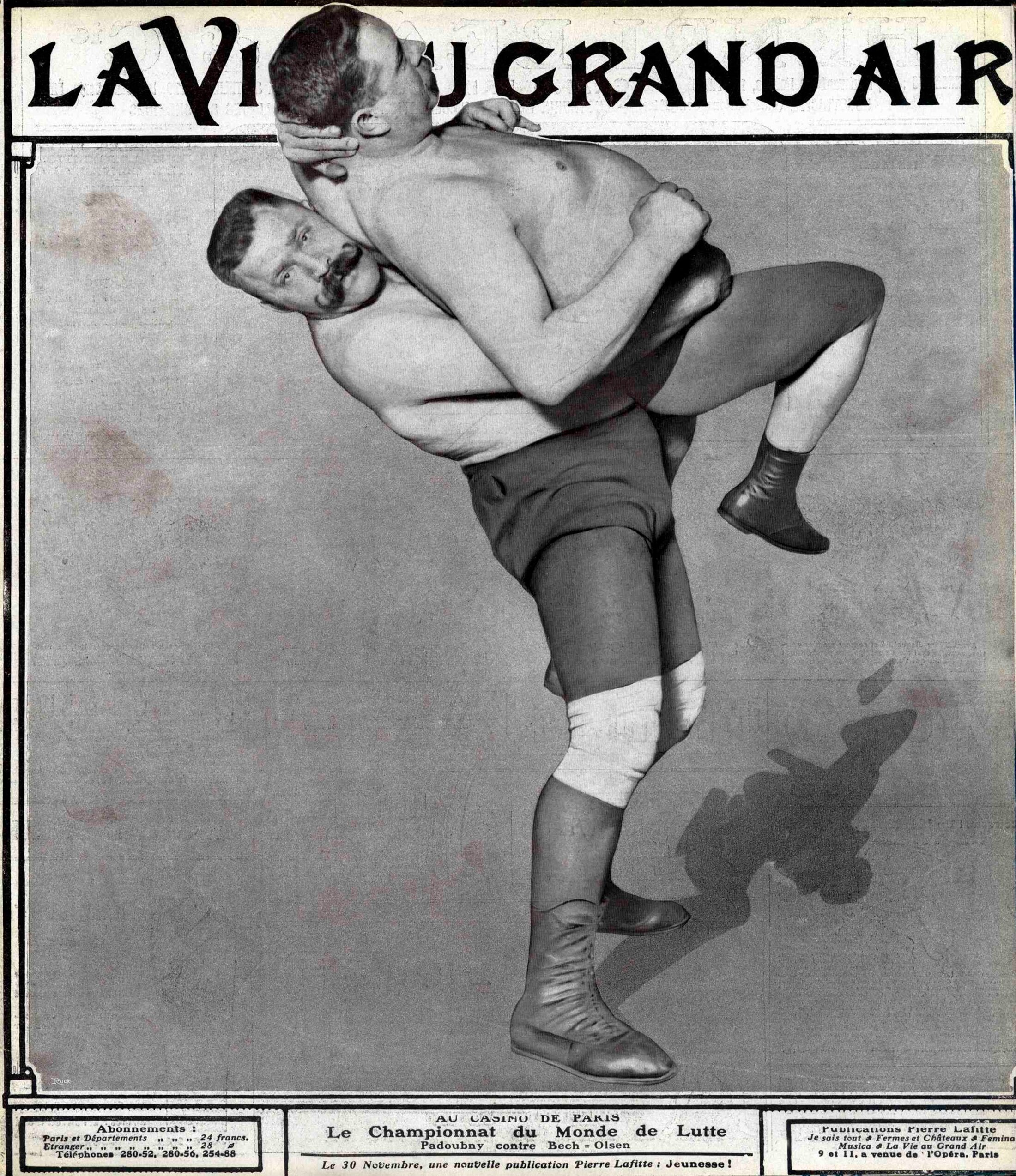

Enlargement : Illustration 9

Georges Vigarello:

"I find this picture, which dates back to 1905, both characteristic and fundamental. It's characteristic because it coincides in time with the appearance of sport, as in institutionalised practices, championships, sports trips, federations, offices, all of which have little in common with aristocratic traditions.

It's fundamental because on this cover of the magazine La Vie au grand air [Life in the Open Air], the major sports magazine of the early 20th century, what's held in high esteem is boxing and wrestling. Wrestling was then the sport that attracted the most people, seduced the public, embodied the qualities of masculine competition: strength and combat. Wrestling would never be as popular and valued today."

Enlargement : Illustration 10

Jean-Jacques Courtine:

"This American image, entitled ‘Wash day. The new generation of housewives,' dates back to the beginning of the 20th century. By exchanging the man and woman trait by trait, task by task, it seems to me emblematic of the major concern that at the end of the 19th century permeated western societies terrified of the ‘degeneration' of male energies, the loss of strength.

The spectre of de-virility that then developed is mainly, though not only, founded on the transformations of women's place in society, particularly in the Anglo-Saxon world, and on the demands for equality and sharing, even if this is still a long way from the 1960s."

Enlargement : Illustration 11

Bruno Nassim Aboudrar:

"This sculpture by Constantin Brancusi is called Torso of Young Man and is dated 1923. It's therefore a torso of a young man, but it's quite difficult to see it other than as a phallic figure, particularly pure and glorious, but at the same time truncated. Indeed, this sculpture shows no sign of a torso, no navel, no chest.

In this phallic figure, erect but truncated, we can therefore see, at one and the same time, phallic glory and, already, doubt. The way it has been truncated also makes it resemble a famous sculpture, the Delos Phallus, which we only know as truncated."

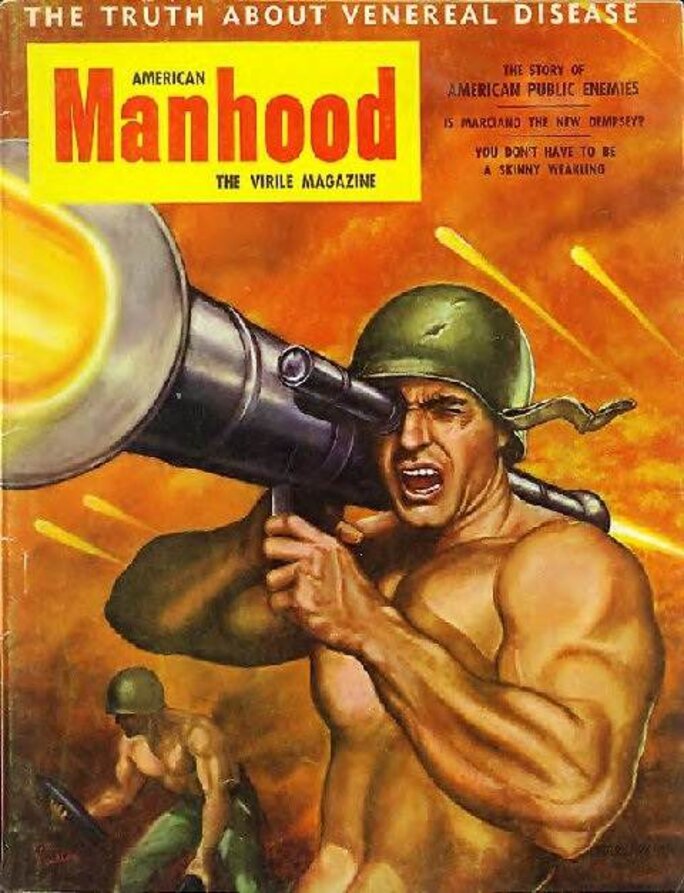

Enlargement : Illustration 12

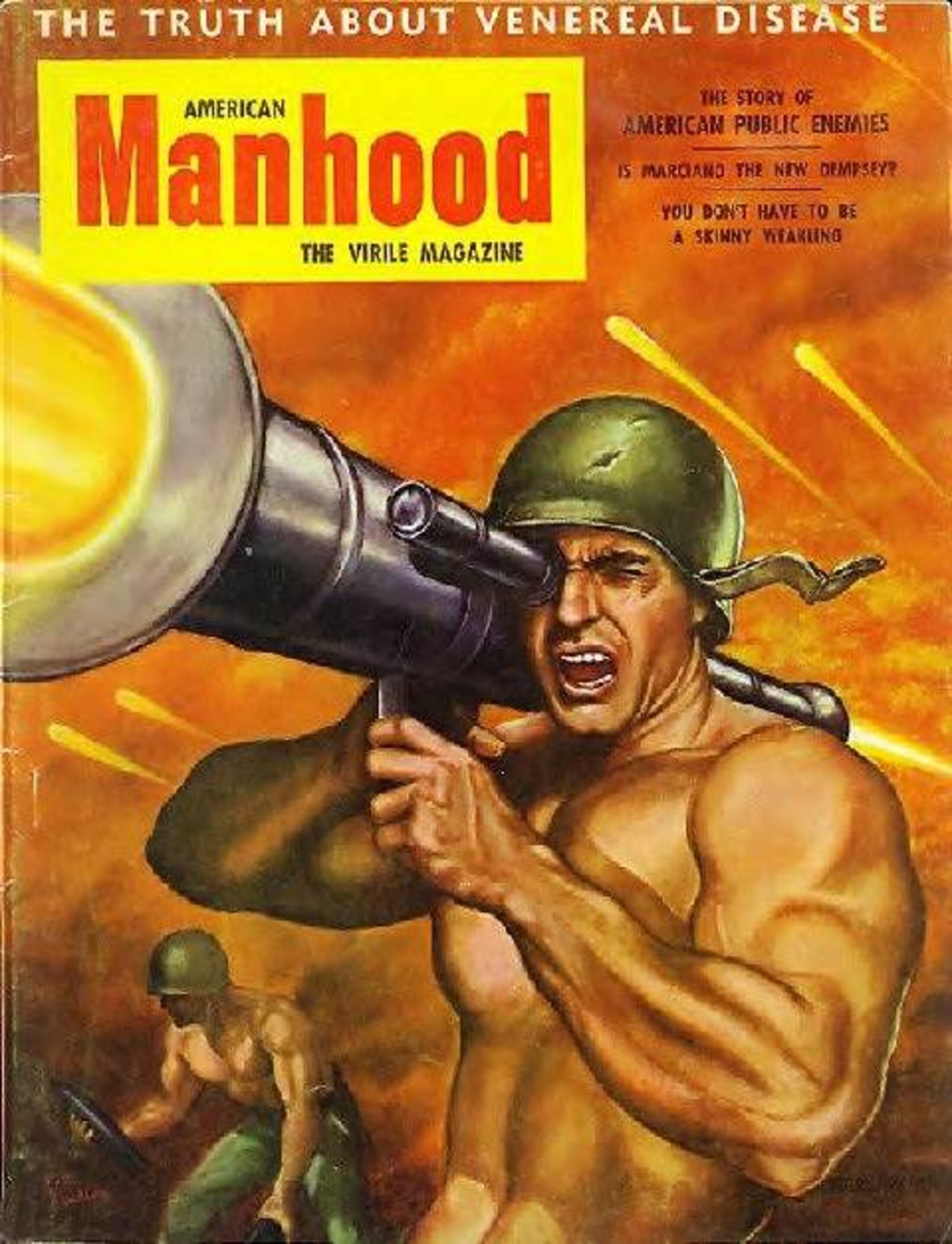

Jean-Jacques Courtine:

"This image is a classic. Representations of the warrior body in the 20th century are based on this model, whether in magazines or in the cinema, if you think of Rambo. The sexualisation of the weapon, which can be found in the marines' songs in Full Metal Jacket, for example, is in the register of the virile tradition that finds its ultimate test in the confrontation of war.

But we're already in the realm of images here, more than in reality, since, even though these representations multiply in the 20th century, the reality of linking virility to war combat has diminished. This over-emphasising of the codes of virility is thus also the sign of a certain weakening. There's a link between the muscular escalation that has taken hold of the representation of masculine bodies and the depth of the concern these bodies have felt."

Now let's untangle body hair, moustaches and beards

Meanwhile, another of the contributers of Histoire de la virilité ('History of Virility'), historian Jean-Marie Le Gall, has further escavated the theme of virility in Un Idéal masculin: barbes et moustaches, XVIe-XVIIIe ('A Masculine Ideal: Beards and Moustaches, between the16th-18th Centuries'), published in France by Payot.

One of the most conspicuous signs certifying virility was indeed, for a long time, facial hair, as is also shown in Histoire du poil, ('History of Facial and Body Hair'), edited by historians Marie-France Auzépy and Joël Cornette, published in France by Belin.

In certain civilizations, they argue, "where the beard makes the man, it's so linked to a man's virility and his honour that that it fulfills the public, social role of the male member." From 1914 to 1933, it was obligatory for French gendarmes to sport a moustache as a sign of authority. Conversely, smooth skin on a woman's legs and pubis has been a defining condition of her femininity and image.

Thus, they write, for a long time "the feminine nude wasn't considered obscene if the pubic hair wasn't represented."

According to psychoanalyst Patrick Avrane, a contributor to the book, Courbet's painting L'Origine du monde (The Origin of the World) would therefore not have caused such a scandal if it weren't for the black patch of pubic hair. Without pubic hair, the painting, he says, would have been more a "pornographic work, or an anatomical illustration, than a work of art, albeit a controversial one."

-------------------------

The three volumes of Histoire de la Virilité are published in France by Seuil, priced 38 euros each.

-------------------------

English version: Chloé Baker and Patricia Brett

(Editing by Graham Tearse)