How many times have we been told that the French version of the #MeToo movement has arrived? Over the years there have been personal testimonies from Adèle Haenel, Vanessa Springora and Camille Kouchner, the case involving newsreader Patrick Poivre d’Arvor (known as PPDA) and so on. And with each powerful intervention by the women involved we have been told that, this time, the movement really has crossed the Atlantic. Every time, however, a counter-offensive has quickly been mounted and the door appears to have slammed shut again. “#MeToo has lots of layers. You always have to add another,” Hélène Devynck, the complainant in the PPDA affair and author of the book 'Impunity', explained in Télérama magazine.

The movement's story in France is one of ups and downs, of advances and resistance. The latest developments, involving allegations about actor Gérard Depardieu, film directors Benoît Jacquot and Jacques Doillon, actor and producer Philippe Caubère, and psychoanalyst Gérard Miller, bear this out. Several prominent figures such as the actress Laure Calamy and the president of the #MeTooMédias collective, Emmanuelle Dancourt, expressed delight at what they saw as a “French #MeToo” or a “second #MeToo”.

Yet a multi-pronged counter-offensive soon swung into action in a bid to stifle the impact of the images shown on 'Complément d’enquête', the television programme which reignited the Depardieu affair in December. This counter-offensive has included fake news relayed by media owned by the Bolloré group, an open letter of support for the actor signed by 56 figures from the world of culture - published with the help of crisis communications specialist Anne Hommel – and, above all, the support of President Emmanuel Macron himself who, going against his culture minister at the time, attacked what he called a “manhunt” and insisted that the actor “makes France proud”.

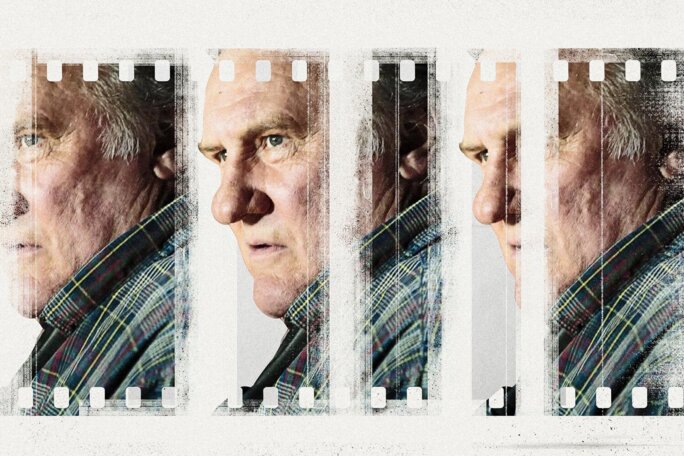

Enlargement : Illustration 1

And reacting to the allegations involving directors Doillon and Jacquot who, along with fellow director Philippe Garrel, himself facing faces allegations of sexual assault, incarnate what is called the 'auteur theory' of French cinema – in which directors are ascribed a pre-eminent and all-powerful role in their profession - commentators were again quick off the blocks. They spoke of a return to the moral order (Le Figaro) or suggested the claims were driven by a search for notoriety on the part of little-known female actors (Jacquot in Le Monde).

There has been strong resistance ever since the arrival of the #MeToo shockwave here in 2017. While the United States debated the limits of #MeToo - not its principle - in France the movement provoked debates in which protagonists still line up 'for' or 'against'.

The media commentator and failed presidential candidate Éric Zemmour compared the hashtag '#BalanceTonPorc' ('Denounce your pig') to that of 'Denounce your Jew'. President Emmanuel Macron, while at the same time launching an action plan to tackle violence against women, said that he “doesn't want a society of denunciation”, while his economy minister Bruno Lemaire explained that he would not inform on a politician if he knew about a case of sexual harassment – before then backtracking.

A very French form of resistance

Three months later, when the Golden Globes speech by Oprah Winfrey – in which she announced that “a new day is on the horizon” for women who had now “become the story” - made the news across the United States, France instead woke up to the 'Deneuve' open letter in which the actress Catherine Deneuve and other celebrities defended the “freedom to bother” against what the letter called “puritanism”, and to the shocking comments of two of the letter's signatories. Radio show host Brigitte Lahaie stated “You can orgasm during a rape,” while art critic Catherine Millet declared “My great regret is not to have been raped [to show that] you can get through rape.”

Two years after that the actress Adèle Haenel staged a walk out of the French film awards ceremony the Césars, in protest against award-winner Roman Polanski, accused of rape by six teenagers. A major controversy followed, including an op-ed article by a hundred lawyers attacking the “triumph of the court of public opinion” and the “worrying presumption of guilt” in relation to the accused men. The actor later quit her successful film career.

In September 2020, when the chef Taku Sekine, accused of sexual violence by several woman, took his life, the #MeToo movement was once again in the dock. “The snitches have won … Tell me, how many bodies do you want?” demanded lawyer Marie Burguburu in an article attacking the “verdict given by the liberation of women's words movement”.

Five months later an avalanche of cases (newsreader and presenter Patrick Poivre d’Arvor, actor Richard Berry, producer Gérard Louvin, artist Claude Lévêque) provoked a fresh op-ed article by lawyers attacking “trial by media” in the country. “In the United States there was a response; in France there was a reaction,” says French historian Laure Murat, who in 2018 wrote an essay on the post-Harvey Weinstein era (see Mediapart's investigation into the issue here).

In the post-#MeToo era in France we have seen a government minister facing rape accusations applauded in Parliament and then promoted; an acting star under judicial investigation for rape received with plaudits in television studios and never questioned on the issue; a director facing several accusations of rape being honoured by the Cinémathèque film organisation and then receiving a César award; a presenter and producer discussing on live television their desire to “slap” a militant feminist; and a well-known actor provoking laughter in a television studio by explaining that at museums he had a habit of getting his penis out in front of astonished visitors.

Meanwhile, some of the women reporting sexual violence have been described as “sluts”, “prostitutes” or “liars”, and accused of being “upstarts” in search of a “publicity stunt”. Author Hélène Devynck says: “Social control has to change. At the moment it is not conducted against predators but against the victims.”

Is the Depardieu case a turning point?

But some think that this time a turning point has been reached. Actor Judith Godrèche did not name Benoît Jacquot in her acclaimed series 'Icon of French Cinema', a fictionalised account of her own life in which she describes a 14-year-old female actor being groomed by a director. But she did choose to name him when an illuminating 2011 interview with the director later re-emerged.

The open letter defending Depardieu meanwhile turned into a fiasco, with several signatories later backtracking and expressing their “unease” with both its text and the person behind it, who is close to far right commentator Éric Zemmour. “Yes, my signature was another rape,” apologised actor Jacques Weber.

Emmanuel Macron, under fire for his support for Depardieu, sent Brigitte Macron to appear on LCI news channel to support the “courage” of women who speak out, before himself conceding during his January press conference that he should have underlined the importance of “the stories of women who are victims of this violence”.

In another sign of change, just 56 personalities signed the Depardieu open letter, far fewer than the 700 who backed Roman Polanski when he was arrested in Switzerland in 2009. And in an unprecedented development no fewer than six counter-articles were published.

While some figures close to Depardieu have been notable for their absence, such as Catherine Deneuve, in contrast some famous actors have come out in support of the complainants. “Of course I'm in favour, and I support women speaking out with all my heart,” actor Daniel Auteuil said when questioned on the programme 'C à vous' on France 5 television.

Enlargement : Illustration 2

“Gérard Depardieu is just the tip of the iceberg, there's been 50 years of inaction in the cinema world,” said actress Emmanuelle Devos on the '28 Minutes' programme on Arte television and who – in contrast to her words in 2018 concerning Woody Allen – was pleased that a “revolution” was under way. “Those who are against all that, they're off and they will clear off....Those who abused, they will go. That's how it is. But I find that quite healthy,” she said.

The author and director Iris Brey, who has a doctorate in cinema theory, sees these events as a “turning point”. She says: “Before, the majority of actresses, when they were asked during the promotion of a film, simply said 'That's never happened to me.' Today some actresses who have not themselves said '#MeToo' say that they believe the women who have spoken out.”

In her view, this change has been made possible by images and stories which bring home the point of view and mindset of the victims. “The series by Judith Godrèche allows us to get the assaulted girl's point of view, which was not the case in either the Benoît Jacquot film, nor the Gérard Miller documentary in which he spoke. The account by Neige Sinno [editor's note, the autobiographical 'Triste Tigre' or 'Sad Tiger' published by P.O.L, which recounts the story of incest of which she was a victim] expresses a new way in which to look at stories, to question the point of view. The raw footage from 'Complément d’Enquête' [editor's note, the television programme in December which sparked the latest Depardieu affair] permitted Depardieu to be shown in the image of an aggressor.”

#MeToo and its 'counter-story'

Rather than a genuine turning point, historian Laure Murat herself sees the latest developments as a “jolt”. She says: “Just as the Deneuve open letter had brought together a certain number of people, so the Depardieu open letter showed a climbdown. The Year 1 of #MeToo (2018-2023) has drawn to a close, a sort of Year Zero. But we're still a long way from Year 2. You don't change a society's morals in six years.”

This specialist in cultural and literary history, who teaches at the University of California Los Angeles (UCLA), notes that “for the first time” the hostile stance towards #MeToo, which is expressed through attacks on “ayatollahs of morality” and “packs” and by misusing the concept of the presumption of innocence without a word for the complainants, seems to be “on its last legs”.

She accounts for this through a shift in public opinion and the increasing level of criticism on social media. “The new factor is that by changing direction the pressure of public opinion has suddenly made the signatories to the Depardieu open letter fear for their careers and reputation,” Laure Murat says.

But if the change took place over the Depardieu affair, then “this is because he had a go at a child [editor's note, by sexualising them, according to the images from 'Complément d’Enquête'].” Laure Murat continues: “In France we rightly think that the real scandal is to attack children. But with women, we always think there's a doubt over consent. We haven't yet managed to move on to adulthood.”

It's #MeToo's counter-story that brings #MeToo to life in France.

In fact, the most impactful cases in France are often those involving claims of child abuse such as the revelations by Adèle Haenel concerning director Christophe Ruggia, and the major books by Vanessa Springora ('Le Consentement') - about writer Gabriel Matzneff - and Camille Kouchner ('La Familia Grande'), about the incest committed by former university professor and politician Olivier Duhamel. It is also true of the distressing account by Judith Godrèche.

According to Laure Murat, #MeToo owes its existence first and foremost to its 'counter-story': it is the resistance to this movement, with its claims of being “anti-censorship” and “anti-lynch mob”, that has set the movement's rhythm and advanced it. “It's #MeToo's counter-story that brings #MeToo to life in France,” she wrote in an article on Mediapart.

Incomplete revolution

The sociologist and writer Kaoutar Harchi sees these backlashes and the swings between advances and reverses as the “rhythm of emancipation”, in a society where anti-feminism remains “very widespread” and where a “hatred of equality” persists, she told Mediapart in 2023.

This opposition to the struggle against sexist and sexual violence is like the backlash against the LGBTQI+ and anti-racist struggles, she says. “This type of speech [against these movements] is linked to the fact that what is perceived to be the authentic French national identity was built upon a process of social and political undervaluing of the allegedly dangerous popular masses, of supposedly perverted and perverting women, and of foreigners who were said to be enemies,” she says. According to her, there is still a strong influence from a “prescriptive regime that is colonial, masculine and bourgeois”.

The risk of a backlash is not just from a notional anti-feminism. It also takes the concrete form of a rise in sexual and physical violence against women and children. In periods when women's rights are backed by powerful feminist movements the number of complaints of such violence “increase significantly ” the historian Christelle Taraud – the editor of 'Féminicides, une histoire mondiale' ('Femicides, a worldwide story') - has told Mediapart.

“Each time, the growth in figures corresponds to periods of feminist high points. In contrast, when women bend and lower the knee, they’re killed less,” she observed, making a correlation between the “#MeToo movement #MeToo and post-#MeToo movement and the pandemic of femicides currently happening everywhere in the world”.

#MeToo has clearly led to some historic advances. Through its sheer scale, both in the real and virtual worlds, it has ensured that the issue of sexual and sexist violence is discussed in households. It has also enabled great progress on the ground in terms of feminist discourse and thought, which have both improved and become more democratic.

Yet it remains an incomplete revolution. “When you ask women what they go through, terrible stories emerge,” says Kaoutar Harchi. “Things are moving a lot, it's likes the ground is trembling under our feet, but the sky itself is still pretty much the same.”

--------------------------------------------------------------------------

- The original French version of this article can be found here.

English version by Michael Streeter