The body was that of a male terrorist aged 28. “Very olive skin” with “dark brown hair” and “closely cut brown moustache and beard”, notes the report. Inside the autopsy room of the forensic mortuary at the Institut Médico-Légal (IML) in Paris's 12th arrondissement (district), a gendarme, two medical examiners, a police forensics officer and a police photographer are standing around the body which is lying on a trolley. It is 8.40am on Friday 20th 2015, and Dr Antoine T. is starting the post-mortem examination.

The examiner starts to remove the clothing from the corpse which is labelled 'IML-2587'. The remains of cropped trousers and the remaining half of a German national football shirt are removed. The dead terrorist weighs no more than 72 kilos, not including the 50 or so nuts and bolts that x-rays show are now lodged in the deceased's kidneys, stomach, pancreas and intestines.

In jihadist mythology the scent of musk envelopes the bodies of brothers who have died in arms, and they are said to have a smile on their faces as they accept death with serenity. But corpse IML-2587 was not smiling. Its jaw was missing and only four teeth survived. The “large cheek” described in a report by the French internal security agency the DGSI when he was still alive was no more. The gaping skull was empty and the corpse's body had not fared much better; the ribcage had been destroyed, the abdominal wall was gone and the intestines laid bare.

It was the body of Abdelhamid Abaaoud.

As this report details, Abaaoud, a member of the Islamic State's security service or Amniyat, who was in charge of recruiting then coordinating people smuggled secretly into Europe to carry out attacks, lived jihad like a game.

The many different sources of information on which this investigation is based are listed in the 'Boîte noire' (black box) section at the bottom of this page.

Abaaoud owes his notoriety to a video broadcast on March 20th 2014, in which he appeared at the wheel of a 4 x 4 vehicle dragging bodies to a communal grave in Syria. The Belgian with a Moroccan background joked: “Before, we used to tow jet skis, quad bikes, motocross bikes and large trailers full of luggage and presents to go on holiday.” Referring to the bodies at the back he said: “You can film my new trailer!” Three months later he was pictured on Facebook with a friend, posing with a gun. The caption on his selfie referred to “terrorist tourists”.

His rise inside Islamic State's self-styled state and its security apparatus was due to his zeal and his lavishness with money. In Belgium his father was a miner who, through sheer hard work, became well-off while his now-wealthy mother “had become a snob” who did not speak to the rest of the family, according to one member of it. Abaaoud found himself the owner of a house and several shops. His fellow terrorist and friend from childhood, Mohamed Abrini, said: “In truth, he lived the good life.” It was with this family money that the middle class boy from Molenbeek in Belgium went on to climb up the ranks of the IS hierarchy.

After being radicalised during a spell in prison Abaaoud, who had until then been a party animal, sold the business he had inherited from his father and at the start of 2013 headed for Syria. Here he made himself indispensable inside the al-Muhajireen brigade, largely made up of immigrants, which fought against the Syrian regime in the civil war. “With his money they bought the weapons they needed,” said Abrini.

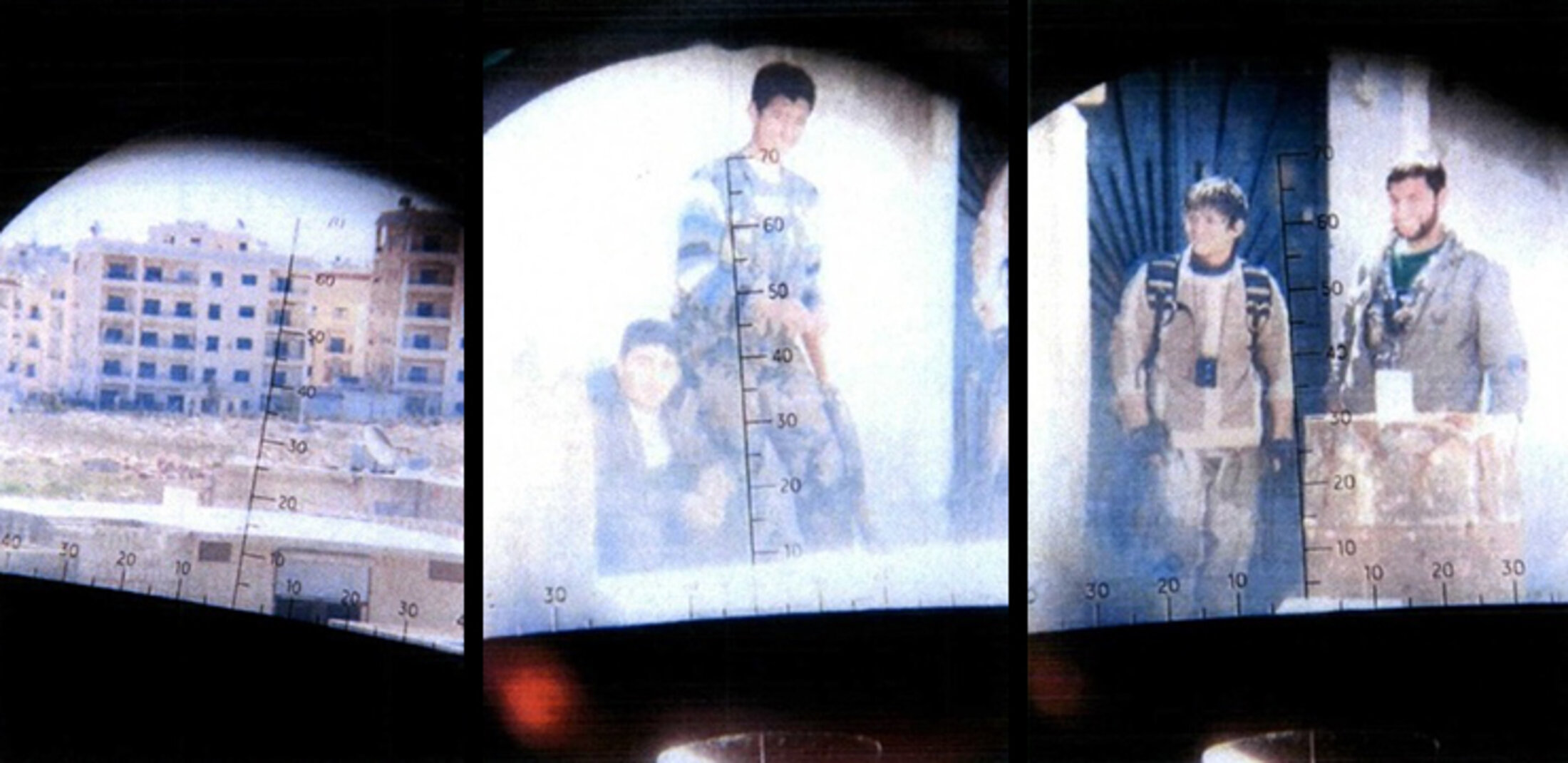

From being a simple fighter Abdelhamid Abaaoud moved up the ranks and became over time the 'emir' of the al-Battar brigade in the Deir-ez-Zor area of eastern Syria where Islamic State and Bashar al-Assad's army fought it out over a military airport. According to Abrini, Abaaoud commanded a unit of a thousand French-speakers, though France's external intelligence service, the DGSE, put the figure at 170. He planned battles, was grazed by a sniper's bullet and was then recruited by the unit in charge of external operations inside the IS security service Amniyat. At the time the DGSE wrote a report on him entitled: “Abdelhamid Abaaoud, key player in the threat aimed at Europe”. This report on September 9th 2015, concluded with the words “in the current state of the Service's access and capability no preventative action can be carried out in the short term”.

Two-and-a-half months later, on November 13th, an onlooker used his mobile phone to film a man dressed in black with orange footwear shooting “without any rush” the customers of the Belle Équipe restaurant in rue de Charonne in Paris. While he was subsequently on the run he boasted to a female cousin and a friend of hers: “The [restaurant] terraces, that was me!” He claimed no fewer than ten successful attacks.

His macabre odyssey ended on November 18th, 2015, amid the sound and fury of a badly carried out assault by the specialist police unit RAID on the third floor of a rundown building at Saint-Denis in the northern suburbs of Paris. Abaaoud's disfigured body was found in the living room while his cousin suffocated in the ruins.

At the forensic mortuary in Paris the gendarme warrant officer who had been present during the terrorist's post-mortem examination took dictation from the forensic pathologist and wrote down the cause of death as the “consequence of very serious and instantly fatal multiple trauma”. Unharmed by the 1,500 shots fired by the RAID officers, the Belgian had succumbed to the blast caused by another jihadist's explosive belt.

The mystery of this mass crime of November 13th 2015, was quickly resolved and the killers killed. Contrary to what Islamic State had counted on happening, the military success of the attack ended up as a political defeat; for the International Coalition's bombings carried on, and day by day the Caliphate crumbled. And yet in France and Europe in general the issue of public safety remains. Abdelhamid Abaaoud has come back to haunt us.

When he met his cousin and her friend the Belgian terrorist, who was hiding in a bush on the ring road at Aubervilliers, in the north-east suburbs of Paris, told them that 90 suicide fighters were hiding in the Paris region. These were people who would “pass for normal in everyday life … they have enough to eat ...they're fine,” his cousin's friend recalls him saying. “He said they'd do worse … that everything was ready,” the friend added.

This evidence corroborates a report that France's domestic intelligence service the DGSI received in the summer of 2015 stating that “a group of 60 fighters are preparing attacks in Europe, most particularly in France, in Germany and in Belgium”. At the beginning of 2016 the French services alerted the country's highest authorities: “The intelligence gathered on the presence of operatives already present in Europe is growing in number and reflects the 'broadening' of attack plans.”

Abdelhamid Abaaoud has instilled terror and doubt. European security services are now chasing his 90 phantom figures.

The discreet charm of the plotter's flat

Just six rather than 90 terrorists went to ground at the duplex flat in rue Henri-Bergé at Schaerbeek near Brussels, a hideout for Islamic State operatives who did not take part in the murderous attacks in Paris on November 13th 2015. They included Mohamed Abrini, Osama Krayem and Salah Abdeslam who at the last minute pulled out of the Paris attack. And while the whole world's media spoke of this massacre which left 130 dead and 400 injured, they did not say a word about it.

“After the attacks … it was so confused that no one was supposed to go out and no one spoke of what happened. It was a period of silence, “ Krayem, a Swede, said later. To pass the time the terrorists instead played on their PlayStations. “The contrast was crazy, you could make a film of it,” Abrini later said, describing how one mujahideen in the room was surfing the internet, another was on their PlayStation console while “[a third] was perhaps above making bombs”.

“Above” referred to the first floor of the duplex where the ceiling was higher and where the windows remained open because of the “unbearable” smell. Here there was a sewing machine which was “the nicest object of all the objects there”, a bag filled with powder that would be used to make the explosive, various threads, lots of nuts and bolts and the person of Najim Laachraoui, who had been designated to make the explosive belts for the next suicide attackers.

A scientist by training and a former IS jailer in Aleppo, Laachraoui had a different status to the others. He was the only one not obliged to share a room and the only one who had a phone, a tablet and a laptop.

Laachraou, who was also a black belt in karate, had always been very pious. “One day on the television we saw that someone had burnt the Koran in the United States or Denmark and Najim cried the whole day,” said his father, who tried in vain to reason with him once in Syria by phone. “When I asked him to return home he hung up...”

The French external intelligence agency the DGSE describe Laachraoui as an “influential figure in the jihadist scene in Raqqa” who had quickly become “one of the terrorists charged with planning Islamic State operations in Europe”. This can be explained by his technical ability, his burning desire to attack the West - “He was determined...for him there was no going back” said Osama Krayem – and perhaps, too, because he had been spotted by the creator of the self-styled Caliphate's “Stasi” - its secret police and intelligence unit the Amniyat.

Laachraoui boasted on his Twitter account in November 2014 that he had spent five days in the same maqar or house as Haji Bakr. This former colonel in the Iraqi army who was the “architect” of the IS's Amniyat (see first article in the series here), had been killed eleven months earlier by the Free Syrian Army.

Laachraoui's message on social media is ambiguous. Did he visit one of the founding fathers of IS when the latter was still alive? Or had he simply had the honour of sleeping in the dead man's house? Or was it just all a vision? When one of his Islamist friends suggested this, Laachraoui retorted: “It wasn't a dream,” without saying any more. In a note revealed by German publication Der Spiegel, Haji Bakr had said in relation to the “more intelligent” jihadi recruits: “We're going to train them for a while before releasing them into the wild.”

***

All of a sudden the group had to leave the cosy bolthole, on the order of the el-Bakraoui brothers, Ibrahim and Khalid, who were the group's logistics experts. The Belgian police had begun searches in the area. So the IS operatives donned wigs and glasses and put their weapons in holdalls; a previous group in Verviers in Belgium, led by Abaaoud, had hidden 250 rounds of various calibres in an Armani bag. At Schaerbeck the tablets were broken and thrown in bins. Only Laachraoui had the right to take his laptop with him.

A book known as the Al Qaeda Manual dating from the 1990s had laid out the procedure to respect in case the police came. It recommended that members of a group worked out in advance who was to carry what and who would be responsible for destroying those items that should not be kept.

Enlargement : Illustration 4

At Jette near Molenbeek in Brussels the six members of the group had to squeeze into a damp studio flat. Because of the lack of airflow it was decided that the making of explosive belts had to be temporarily abandoned. “[Otherwise] you'd have found us dead well before the attacks,” said Abrini ironically. The cramped conditions led to tensions within the group. Salah Abdeslam was very nervous and rowed a lot with Najim Laachraoui. Abrini and Abdeslam, the only ones to have their photos and identities circulated by the authorities, followed the investigation's developments “day after day” on the internet and smoked cigarettes on the balcony before carefully closing the shutters behind them.

These two men were not allowed to go out and Osama Krayem took care of the shopping; Ibrahim el-Bakraoui had left between 5,000 euros and 10,000 euros in each bolthole. Meanwhile Salah Abdeslam spent his time in front of the stove. “He was a good cook,” recalls Krayem. Then, after a fortnight of this monastic lifestyle, they had to leave Jette. Ibrahim el-Bakraoui told the group that he had received a letter from an inmate at a Belgian jail telling them to leave “because the police knew where they were”.

At this point the group divided; Abdeslam and two others went to stay at Forest while Abrini, Krayem and Lachraaoui returned to Schaerbeek, in a flat on rue Max-Roos. Here some Kalashnikov rifles were stored in a cupboard and a plastic case “filled with white powder” stood next to a dumbbell in the room used by Laachraoui. Osama Krayem said this felt quite normal as far as they were concerned. “When someone has lived in Syria it's nothing to have a bomb next to them … The Westerners … will never understand the way we think!”

***

From the calm of the flat in rue Max-Roos Laachraoui made contact with Syria from his computer. He left some audio messages on a digital dead letter box for “Abu Ahmed”, who according to Belgian police was a “suspected Emir of the Islamic State in Syria”. Having greeted the “brigade's brothers” Laachraoui talks about the situation and mentions potential targets. “And we had spoken to you about England .. yeah, that, we forgot, you see?” he says of the country where Mohamed Abrini had gone eight months earlier. Finally Laachraoui questions his Emir on the operational method to adopt: “How should one do it? A major operation where we all go out and that's the end of it?”

It was March 21st 2016 and there was no time to beat around the bush.

Six days earlier the police had raided the hideout in Forest near Brussels and one terrorist had been killed. Abdeslam escaped before being arrested alive on March 18th. Meanwhile a photo of the el-Bakraoui brothers was published in the press. Ibrahim stayed glued to the television in the flat in rue Max-Roos and was “not happy and even a bit shocked”, said Osama Krayem. “He wasn't expecting the police to arrive. He wasn't expecting for this hideaway to be discovered.”

Then Najim Laachraoui left a final message for Abu Ahmed. Despite the rush the group had picked up information from a “brother” about Zaventem, Brussels' airport. “In the morning there are American flights, Russian flights, Israeli flights. We're going to try to hit them,” he declared. There was no time left to prepare the attack, no time left to hit France or Britain. Laachraoui was going to hit the nearest target, Brussels. “Inch'Allah the targets will be … the airport and the metro lines. You see? The most immediate.”

The operations centre for attacks

The other el-Bakraoui brother, Khalid, sent Swede Osama Krayem to ask passers-by which was the closet metro entrance. For though Khalid el-Bakraoui had grown up on the outskirts of Brussels he was lost. But when on March 22nd 2016, they got to the nearest metro entrance Osama told Khalid he would not go into it with him. Khalid el-Bakraoui shouted at him in the middle of the street and then, at the end of the altercation, went down into the station. He got on board a carriage and blew it up, killing 17 people. Osama meanwhile went and emptied the contents of his explosive jacket in the toilets.

Just an hour earlier Ibrahim el-Bakraoui and Najim Laachraoui had killed 15 people in their suicide bombing mission at Zaventem Airport. As for Mohamed Abrini, having pushed an explosive device in a luggage trolley, he decided against heading for paradise and instead went on the run.

This meant that one terrorist, Khalid el-Bakraoui, had got lost in the city where he was born while three others (if one includes Abdeslam's failure to join the Paris attack) had refused to die. There had also been Sid-Ahmed Ghlam who shot himself in the thigh, thus preventing him from carrying out an attack on a church at Villejuif near Paris in 2015, and in the same year there was the case of Ayoub el-Khazzani who was armed to the teeth yet who was disarmed by three tipsy American soldiers on a train. The IS groups were well used to working in secret but sometimes less effective when it came to the attack itself.

IS shared this pointed of view. Abdelhamid Abaaoud told his cousin and friend that he had “come to France to lead the suicide bombers because there has already been a lot of failures”. The DGSE considers that their “particularly flexible method of operation” gives the IS groups considerable adaptability in the carrying out of terrorist attacks. But “its corollary is the uncertain effectiveness of the attempted actions, dependent on young and inexperienced participants”.

Yet despite the incompetence of some of its fighters Islamic State can claim 317 deaths and 1,458 injured during the 17 attacks carried out in the European Union in the last three years up to September 2017 (on top of more than 1,500 deaths in the rest of the world). The jihadists may be fallible but the unit in charge of external attacks inside the Amniyat remains formidable.

Western intelligence services have failed to hold them in check. In France several spies have sensed the approaching danger and some wrote notes that were passed on to the highest levels of state. But like their American cousins before 9/11 these agencies underestimated the nature of the adversary they were facing. They focussed their attention on the solders, who were portrayed as empty-headed, destitute or people with psychiatric disorders. And when, in the summer of 2015, they finally grasped that their enemy had a knowledge of counter-espionage and logistics like that of any state apparatus it was too late.

In the United States of the 1920s the emergence of the criminal underworld gave rise to the notion of organised crime. Today with Islamic State it is appropriate to talk about organised terrorism.

***

One note from France's external intelligence agency makes this point:

DGSE – DEFENCE CONFIDENTIAL - February 19th 2016 – No83645 – THE PROJECTED DECISION-MAKING CHAIN OF THE ISLAMIC STATE THREAT

The intelligence drawn from recent attacks carried out in the Levant by Islamic State (IS) has enabled us to prove the existence of a structured decision-making chain, responsible for the terrorist organisation's external operations …

The common points between the latest external operations:

- line of command involving the organisation's high command

- existence of levels of operational supervision

- centralisation of the planning of operations

The increase in number and the professionalisation of Islamic State's operations planning result from the progressive consolidation of the framework formed by the organisation's intermediate level leaders.

***

Three months after this note was written, Bernard Bajolet, at the time head of the DGSE, told an parliamentary committee of inquiry: “We now have good knowledge of the organogram and the organisational method of the so-called Islamic State … we have indeed made progress on these issues.” He did not want to say more. Here Mediapart tries to fill in the gaps.

The organisation's high command

The first rung is the Caliph. According to Osama Krayem, Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi received Abdelhamid Abaaoud “around a table in Iraq” to talk about the plan for the November 13th Paris attack. Otherwise the first person consulted, the person whom the DGSE says “oversees the structure based at Raqqa” - when it still existed - was Sheikh Abu Mohamed al-Adnani. With his deep knowledge of the Koran and Islamic law, the IS spokesman brought a note of caution to the projects that were agreed on.

Less well-known is the role played by Ali Moussa al-Shawak, alias Abu Luqman, the man who supposedly ordered the execution of the English MI6 mole in Aleppo (see the second article in this series here). A member of the Aqeedat tribe, this Syrian law professor who is also a graduate of the military academy at Homs, was close to Abu Musab al-Zarqawi, the founder of Al Qaeda in Iraq, the forerunner to IS. According to the United Nations, in July 2015 Luqman was named wali or “prefect” in Raqqa and the IS's head of security. As such he ran the Amniyat and is regarded as being implicated in the November 13th Paris attacks and the March 2016 attacks in Belgium, even if as far as Mediapart is aware there is no material proof of this.

Operational supervision

Several French-speakers who worked under the orders of Abu Luqman in Aleppo in 2014 were involved in these attacks. Najim Laachraoui, of course, is one, but also Abu Ahmed from whom he took his orders. His real name is Oussama Atar, a Belgian, who led the transfer of Western prisoners from Aleppo to Raqqa in January 2014. These two Belgian terrorists were not the only ones to feature on the list.

Enlargement : Illustration 7

Before hastening to Zaventem Airport Laachraoui had targeted another form of mass transportation and wanted to know how many kilos of explosives would be needed to knock over a moving train. In a message to Abu Ahmed he had once asked for someone called “Mahmoud” to carry out a test on an decommissioned railway line “on the outskirts of Raqqa”. The Belgian daily newspapers Dernière Heure and La Libre Belgique revealed that “Mahmoud” is really Ahmad Alkhald, a 25-year-old from Aleppo who while in Belgium between September and October 2015 made the explosive belts that were later used in Paris on November 13th, before returning to Syria.

Najim Laachraoui had his doubts about the railway as a target. Before heading to Europe to commit his crimes there he apparently consulted another specialist called “Mohamed Ali”. Laachraoui said: “He told me, for that, you need a plasma saw, you see? Secondly ... at the moment that you're going to cut the pieces of rail, there are sensors between them. So when you're about to remove one end of the rail ...well, that will be seen by the people who are in charge of railway security...”

Officially the Mohamed Ali who was consulted on the feasibility of such an attack has not been identified. Police and anti-terrorist judges strongly consider him to be Salim Benghalem. And not simply because, along with Atar and Laachraoui, he guarded Western prisoners in Aleppo.

Benghalem, a construction site driver in France, started his career in the Islamic State driving lorries. During one phonetap he is heard saying how he “missed a crazy opportunity”, to join a hit squad, because he is “more useful elsewhere, in the machines there...” But despite his technical uses he ended up joining the external operations branch of the Amniyat where, according to the French domestic intelligence service DGSI, he enjoyed the trust of “important IS leaders”.

Finally there is the matter of his kounya, his assumed name or nom de guerre. Originally Benghalem chose the name Abu Mohamed al-Faranzi, with the last part meaning 'the Frenchman'. But there were many people in Syria at the time to whom this name could apply. So as a Facebook page created by his brother shows, Salim Benghalem instead chose the full name of his son who was born after a troubled pregnancy in which the unborn baby kicked out or 'boxed' inside his mother more than is usual. As a tribute to this they called him Mohamed Ali.

'We're going to kill your supporters!'

Two days before the Brussels attacks the DGSI arrested Reda Kriket, an armed robber from the Paris region who had been part of the same Molenbeek network as Abaaoud and Laachraoui. At a hideaway in the north-west Paris suburb of Argenteuil, police discovered five Kalashnikovs, seven handguns and, in a Tupperware box, a kilo of TATP, the explosive used in both the Paris and Brussels attacks. As Mediapart had revealed, the investigators suspected Boubaker al-Hakim of being involved in the “conception and running” of Kriket's planned attack. According to Le Monde, after the discovery of the weapons haul one accomplice apparently sent a message via the encrypted message system Telegram to a contact in Syria, who asked him for his “guarantor”. The accomplice responded: “Listen, I've got Abu Muqatil. If he's close to you you can ask him!”

A few months later the DGSI wrote that the role of Boubaker al-Hakim - alias Abu Muqatil - had “recently” been highlighted in the “cell charged with external operations” and that he was planning attacks targeting Europe and North Africa. Could it be that this was the Tunisian based at Raqqa who spoke “very good French” whom the convert Nicolas Moreau said was the person who validated the “dossiers”, the plans for attacks selected by Abdelhamid Abaaoud?

All the jihadists in Syria knew Boubaker al-Hakim. Another convert questioned by the DGSI also mentioned this “high-placed” figure who “led the special forces group and who is contact with the IS spokesperson [Abu Mohamed al-Adnani]”. A third person recalled a cautious person who switched cars each time he travelled, sometimes using a taxi, sometimes a 4x4.

Boubaker al-Hakim had had no problem becoming part of the Amniyat hierarchy. He had gone to Iraq in 2003 just as it was about to be invaded by the United States. In Fallujah, the fiefdom of Abu Musab al-Zarqawi, el-Hakim oversaw the division of French and Tunisian volunteers into different groups and laid the 80kg mines which he set off when American convoys passed by. He was even congratulated by an imam, Sheikh Abdullah al-Janabi who, ten years later, would be a key preacher for Islamic State. When he returned to France el-Hakim boasted of having used flame-throwers.

Boubaker al-Hakim was an example of what the intelligence services and others describe as the “recycling of old global jihadi networks”. Islamic State relied on “around twenty French Al Qaeda veterans” to “carry out complex attacks on our territory”, say the intelligence services. They were the well-known “middlemen” in the organisation's ranks who provided the vital link between the terrorists on the ground and the leaders of the Caliphate.

During his conversation on Telegram Reda Kriket's accomplice had begged for help to be given in the name of a second guarantor “Abu Mouthana”. This was the alias of Abdelnacer Benyoucef, formerly of the Moroccan Islamic Combatant Group (GICM), who in the early 2000s had trained in the Pankisi Gorge region of Georgia, a support camp for Al Qaeda troops. In Syria he was the emir of the al-Battar brigade, whose ranks included several members of the units that later carried out the Paris and Brussels attacks. Benyoucef is also the person suspected of being behind the planned attack by Sid Ahmed Ghlam at Villejuif. Meanwhile the aliases of two IS operatives who dealt with Ghlam correspond to those used by Abdelhamid Abaaoud and Oussama Atar.

During preparations by the IS group in Verviers in Belgium and ahead of the Villejuif attack there was also mention of an old friend of Benyoucef called Samir Nouad, a veteran of the Armed Islamic Group or GIA in Algeria who had subsequently been in Afghanistan. In a note sent to the Élysée in the autumn of 2016 the French intelligence services highlighted how “between January 2015 and April 2016 Abdelnacer Benyoucef, Boubaker el-Hakim and Samir Nouad all appeared involved in projects targeting Europe planned from the Syrian-Iraqi zone”.

Enlargement : Illustration 8

***

Speaking from the Élysée after a meeting of the defence and security committee held on July 16th, 2016, in the wake of the Nice massacre, the then-interior minister Bernard Cazeneuve highlighted the “significant number” of attacks that had been thwarted thanks to the state's actions, in particular during the Euro 2016 football tournament that had just ended.

The minister was doubtless basing his remarks on the expert analysis of Najim Laachraoui's computer that had been found in a rubbish bin in Schaerbeek. In a message the bomb maker, who at the time was planning to attack France rather than Belgium, asked for the Islamic State's press service to prepare a statement stating: “This year there won't be any Euro! And we'll going to make you lose, we're going to kill your supporters.”

Questioned a fortnight after the Brussels attacks, the reluctant suicide bombers Abrini and Krayem confirmed the tournament had been a target. “They wanted to get the Euro football cancelled,” said Abrini. Krayem, meanwhile, played the fool during questioning.

“Perhaps … you're worried about Euro 2016,” he said.

“Why are you speaking about Euro 2016?”

“No, I offered that comment...”

Previously the terrorists had researched targets as varied as the Saint-Cyr Military Academy near Rennes in western France, nuclear power stations, the Port of Antwerp, bars in Brussels and the fundamentalist Catholic association Civitas.

From his base in Syria Salim Benghalem looked at an online report by Le Figaro Magazine on the DGSE and remembered where the secret services were based. Meanwhile, before trying to join IS a woman photographed an official order at a small claims court at Mâcon in east-central France that listed the identities of the police and gendarme officers authorised to validate proxy votes for elections in their area.

In recent months emergency service centres in the Paris region have been reconnoitred, with unknown figures on the public highway making sketches, taking photos and noting the call out times. One such person even made a video on their iPad before fleeing. In 2014 the Islamist in charge in France of verifying the declarations made by aspiring jihadists in Syria installed a spy camera opposite a building to film the comings and goings. At the time he had shown a desire to “blow himself and other people up with an explosive belt”.

When, during his July 2016 comments at the Élysée, Bernard Cazeneuve boasted about the “160 arrests linked with a terrorist enterprise” that had taken place since the start of that year, he neglected to mention that not one of them was linked with the “significant number of attacks” claimed to have been foiled during Euro 2016.

The reason for this, perhaps, was that out of the thirty or so threats dealt with by the anti-terrorist authorities during the sporting event, not one could be shown to be real, according to analysis carried out by the DGSI and corroborated for Mediapart by judicial and police sources. For example, when the tournament was already under way a “major” friendly foreign power alerted the French counter-espionage authorities in good faith to a Syrian mastermind who was dispatching “20 operatives into Europe” to attack the Louvre Museum in Paris. The problem was that this terrorist sponsor turned out to be a fantasist, and the rest of the information turned out to be equally worthless.

The DGSI regarded the “massive” emergence of such alerts during Euro 2016 as a “deliberate strategy” by Islamic State which it said had an intelligence and security apparatus “capable of disinformation manoeuvres” to slow down and impede the Western secret services with “diversion” tactics.

On June 17th, 2016, the British intelligence services passed on information about an imminent attack on a bar in the Marais district of Paris that is frequented by the lesbian community. The information was precise and credible, the football event had been running for a week and just five days earlier an American jihadist had carried out a massacre at a gay nightclub in Orlando.

“Be smart about how the information is used,” pleaded the British. Their source in Syria was already in the sights of the Amniyat. In Paris police officers were dispatched to stake out the area around the bar. No terrorist came, but the British let it be known that their source had stopped sending information for good. “IS pass on false information to see who the traitors are,” says an intelligence official.

In the autumn of 2016 the French secret services gathered information that Islamic State, faced with a military offensive against their Iraqi stronghold Mosul, wanted another “large-scale attack in the West”. A new November 13th. It was not a decoy this time and Boubaker al-Hakim was involved.

Infiltration in Europe

The voice of the Islamic State is no more. Sheikh Abu Mohamed al-Adnani was killed on August 30th 2016, near Al-Bab in Syria. A rumour did the rounds of the jihadists that he had been taken out by Abu Luqman, the head of the Amniyat who wanted to take his place at the right hand of the Caliph, until the Americans then publicly said that their missile had killed the IS spokesman.

Enlargement : Illustration 9

Far removed from such gossip, the Franco-Tunisian Boubaker al-Hakim, who was close to both men, was working hard on several fronts. In September of that year he ordered a bomb maker to carry our attacks against Christians in Morocco. In October he contemplated attacks on tourists in Algeria and was in contact with a Syrian in Germany about making an explosive belt.

In November 2016 France's domestic intelligence agency the DGSI identified him as the person behind plans for an attack that had been planned for several months by two people from Alsace in north-east France, both “Islamic State operatives” according to the tip-off passed by a powerful foreign intelligence agency. A second security agency warned that Germany was being targeted by a Moroccan passing through Marseille in southern France. As L'Express magazine and Mediapart have revealed, these plots were two sides of the same lethal plan being organised by Boubaker al-Hakim. Other potential targets in France were the headquarters of the DGSI and the headquarters of the French Foreign Ministry.

The fighters were arrested in Strasbourg and Marseille on the night of November 19th. A week later, on November 26th, al-Hakim's career as an international terrorist was ended when an American missile wiped him out as he drove around the football stadium at Raqqa where the Amniyat had offices and a prison. According to the French security services his death was an “important event in the fight against terrorism”. One week later the US Pentagon announced the death of three of al-Hakim's assistants suspected of being involved in the November 13th attacks in Paris and with the terrorist cell in Verviers. Again, this attack took place close to the football stadium in Raqqa.

The Western intelligence services had finally woken up and cooperated. Some of the attacks foiled in recent months have occurred thanks to information from Israel's Mossad or Britain's external intelligence agency MI6. The United States has helped France with the eavesdropping capability of its National Security Agency and drone strikes.

Following the targeted executions of its staff the Amniyat reacted by “moving everything” according to a senior official in the fight against terrorism. At the start of 2017 Mossad established that “some leaders involved in the planning of external operations” had moved to Mayadin. This town in eastern Syria had already been visited frequently by Abdelhamid Abaaoud before leading his fighters on the Paris attack.

Among the new residents of Mayadin was Samir Nouad who was in the process of hatching a plan to attack an airliner. He did not have time to put it in operation. On April 22nd 2017, he too was eliminated. During the summer of 2017 the international coalition claimed responsibility for the deaths of around 20 senior figures in Islamic State. However, there was no room for euphoria. For during the same period the attacks in Manchester, London and Barcelona showed that the Amniyat's capacity to strike Europe remained intact.

***

In an interview with daily newspaper Le Parisien on September 10th 2017, France's new interior minister Gérard Collomb focused on the reinforcing of measures to monitor civil servants. The minister was simply echoing the great fear of the security services: that they would be infiltrated by secret IS operatives. At the end of last June a police officer from Kremlin-Bicêtre south of Paris was arrested on suspicion of having consulted police files and accused of having made some explicit remarks to his brother – who had himself been held for his involvement in a jihadist network – about his own support for Islamic State.

The number of cases of infiltration is growing, though we do not know if we are dealing with cases that are being caught in time or whether the hard-pressed intelligence services are imagining plots everywhere. A member of Germany's domestic security agency the BfV, who was accused last year of a suspected bomb plot against the agency's headquarters in Cologne, was given just a one-year suspended prison sentence in September. No evidence of a plot was found and the 52-year-old insisted he had simply posed as an Islamist online as part of a “game”.

In the spring of 2017 it emerged that a FBI translator had spent two years in prison. She had fled to Syria in 2014 to marry a recruiter for Islamic State, the former German rapper Deso Dogg, the man she had been in charge of investigating. And during the summer of 2017 a sergeant in the US army was arrested and charged in Hawaii, after having allegedly tried to send classified documents and provide material support to IS.

“There are many examples of insiders, of infiltrators who are looking to gather information inside civil services or companies,” confirms Yves Trotignon, a former DGSE employee who is today a consultant in risk analysis and lecturer at Science-Po university in Paris. “In 2004 the Hofstad group who went on to kill the Dutch film director Theo Van Gogh had recruited a pharmacist seduced by one of its members. The pharmacist worked opposite the Dutch Parliament and she had access to the medical files of Dutch Members of Parliament and thus to their personal addresses. The terrorists wanted to kill an MP of Somalian origin,” he says.

Over the past two years the organisation that helps co-ordinate anti-terrorist efforts in France, the Unité de Coordination de la Lutte Antiterroriste (UCLAT), has held meetings with representatives from companies and local authorities to make them aware of the threat. Since the creation of the self-styled Caliphate, several sympathisers have taken part in the entry process to join services such as the DGSE and also large companies such as oil giant Total. They have been spotted during the administrative enquiries that take place before candidates are hired. “The situation reminds one of the 1970s when we were faced with the Eastern Bloc,” says one former intelligence agent. “The only difference is that they infiltrated the intelligence services to spy on us. The terrorists infiltrate us to attack us.”

The best-known example remains that of the Jordanian doctor who blew himself up at the Camp Chapman CIA station in Afghanistan in 2009, taking seven American agents with him. To lend credence to his cover story as an informer he had guided drone strikes against lesser Al Qaeda operatives. So when he demanded an urgent meeting the Americans were not suspicious. A recent jihadist manual boasted about this attack, calling it the “worst attack ever carried out against the CIA, including at the time of the Cold War with the KGB”.

***

French police and judges wondered if they, too, were not victims of propaganda when the Belgian Tarik Jadaoun, suspected of involvement in the Brussels and Paris attacks, appeared in May 2017 on an undated Islamic State video. The police file of this man from Verviers, plus those of two other jihadists supposedly on the way to carry out attacks in France, had just been published on Twitter. It led to the evacuation of the Gare du Nord railway station in Paris where a ticket clerk wrongly believed he had recognised the faces of the terrorists.

Moreover, was the broadcast of a video showing Jadaoun in Iraq two weeks later simply the terrorists thumbing their noses, or a decoy aimed at hiding his real presence in Europe? Security officials were left wondering whether the man described by some as the “new Abaaoud” was biding his time, just like the Laachraoui cell which was prepared to wait for eight months before striking, or whether he had actually never left the Caliphate at all. In fact, it has since emerged that Jadaoun is now being held in Iraq and has been questioned by American security officials.

During a committee hearing at the National Assembly in February 2017 Patrick Calvar, then head of the DGSI, reminded politicians that despite their current difficulties “some plans drawn up by Daesh [editor's note, the Arabic name for Islamic State], of the same type as the November 13th, 2015 attack in Paris, have been stopped but we don't know what others are in progress”.

From the Brussels group to the cell in Strasbourg, the European think tank the Center for the Analysis of Terrorism (CAT) has listed 41 Islamic State terrorists as having been arrested or killed in Europe since the summer of 2015. Abdelhamid Abaaoud had spoken of 90 suicide bombers already in place.

-----------------------------------------------------------------------------

- The French version of this article can be found here.

English version by Michael Streeter