It is a situation that has existed for decades but one which has been largely ignored, even hidden: France is the only country in the world which still manages the currencies of its former colonies. More than 70 years after 14 African countries achieved their “independence” from France, they are still using the 'CFA franc' currency which remains under the effective control of the Ministry of Finance in Paris. More and more people in Africa are beginning to criticise a situation which is seen as perpetuating French domination over those countries. In addition many economists warn that the FCFA, as it is known in French, is holding back economic development in the countries that use it.

The CFA franc was officially created on December 26th, 1945. Six years earlier, at the start of World War II, France had already established a “Franc Zone” by passing legislation that brought about changes across its colonial empire. The country's aim was to “protect itself from the structural imbalances in a war economy” and continue to supply itself with low-price raw materials from its colonies. At the time the initials CFA stood for 'colonies françaises d’Afrique' or 'French colonies of Africa', then from 1958 the meaning changed to 'communauté française d’Afrique' or 'French community of Africa'. After France granted independence to its African colonies at the start of the 1960s, the currency system was imposed on the newly-independent states. From then on CFA came to mean 'communauté financière africaine' or 'African financial community' in West Africa and 'coopération financière en Afrique centrale' or 'Financial Cooperation in Central Africa' in Central Africa.

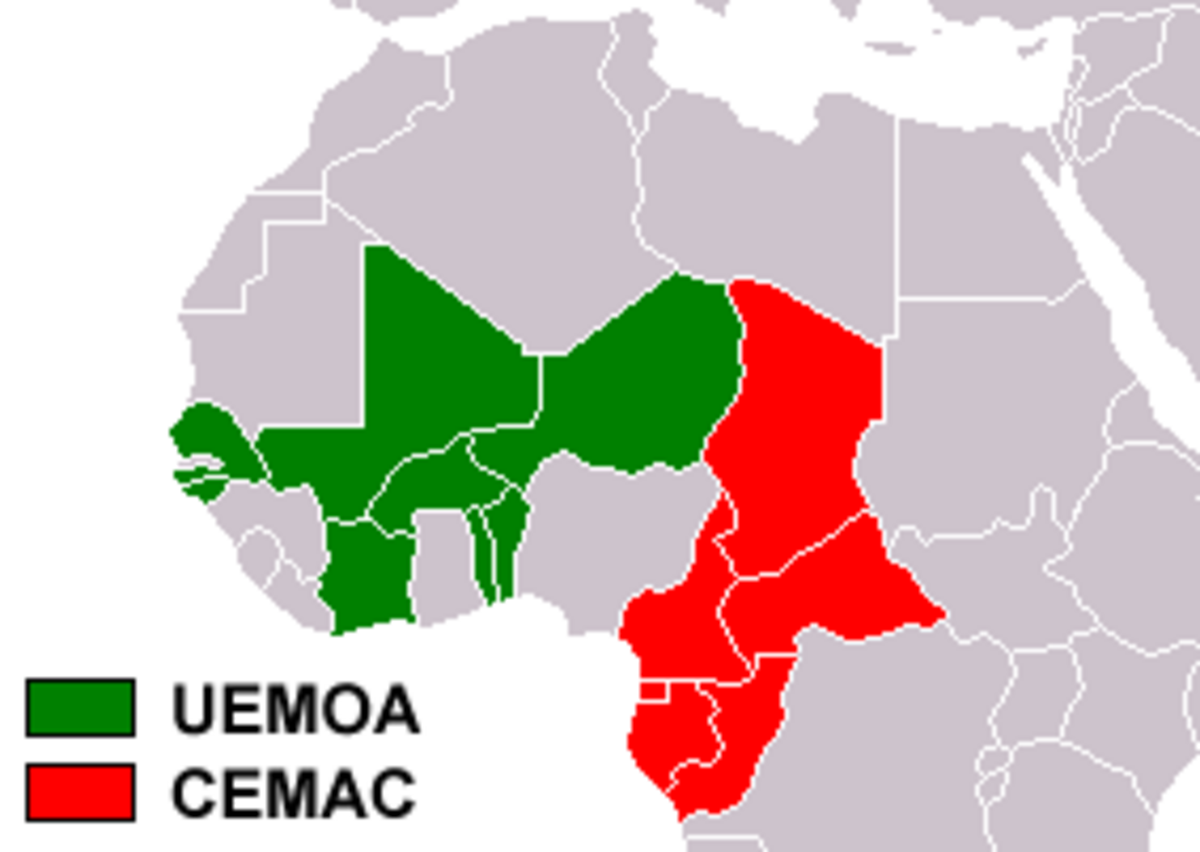

For there are in fact two separate CFA franc currency areas in Africa. In the west there is the UEMOA Union Économique et Monétaire Ouest Africaine (UEMOA) or West African Economic and Monetary Union which has eight member countries, Benin, Burkina Faso, Ivory Coast, Guinea-Bissau, Mali, Niger, Senegal and Togo. In the centre of the continent there is the Communauté Économique et Monétaire de l'Afrique Centrale (CEMAC) or Economic and Monetary Community of Central Africa, whose six members are Cameroon, the Central African Republic, Chad, the Republic of the Congo, Equatorial Guinea (a former Spanish colony which adopted the CFA franc in 1984) and Chad. Each of these groupings have their own central bank. The central bank for West Africa, the BCEAO, is based in Dakar while the central zone's bank, BEAC, is in Yaoundé.

Though both CFA francs are guaranteed by the French Treasury the West African CFA franc cannot be used in Central African countries, while the Central African CFA franc is not legal tender in West African countries. Just to complete the picture another former French colony, the Comoros off the east coast of Africa, is also part of the Franc Zone, though not part of the CFA franc, and has its own central bank.

The Franc Zone rests on four main principles: 1) The French Treasury guarantees the unlimited convertibility of the FCFA into euros (previously the French franc); 2) the exchange rate of the FCFA with the euro is fixed (1 euro = 655.957 CFA francs); 3) to ensure this rate, foreign exchange reserves from the countries in the Franc Zone are centralised in their central banks, who must in turn deposit half of those reserves in a current account called an 'operating account' lodged with the Bank of France and managed by the French Treasury; 4) there is free transfer of capital between the Franc Zone and France.

From France's point of view, and by extension Europe since the arrival of the euro, these rules are of considerable economic interest. Thanks to the fixed FCFA/euro exchange rate France can carry on buying African raw materials such as cacao, coffee, bananas, wood, oil and uranium without drawing on its currency reserves, while its companies can invest in the Franc Zone without the risk of the value of their money depreciating. Thanks to the free circulation of capital there are no obstacles to these companies bringing their profits back into Europe. French multinationals such as Bolloré, Bouygues, Orange and Total have taken particular advantage of this. “This system guarantees profits for European groups, who pay nothing for this guarantee: it's African citizens who, via the currency reserves deposited in the French Treasury, pay for the stability of the exchange rate,” says Bruno Tinel, a senior lecturer in economics at Paris 1 University.

The African exchange reserves deposited in the 'operating accounts' bring France a little money. Of course the African central banks, the BCEAO and the BEAC, also earn on these assets but the returns are low as the assets are aligned to the very accommodating monetary policy of the European Central Bank the ECB. They are paid “at the rate of the marginal lending facility of the European Central Bank (ECB) (1.5% since July 11th, 2012) for the obligatory portion of the deposits, and at the minimum rate of the BCE's main refinancing operations (0.75% since July 11th) for assets deposed above the obligatory portion,” says the French Treasury's own website. Meanwhile nothing stops the French Treasury from investing these African assets at better rates, when monetary conditions allow, and pocketing the difference.

In 1996 the president of Gabon, Omar Bongo, explained: “When you ask a French person in the street he'll tell you: 'Ah, we spend a lot of money on Africa.' But he doesn't know that France collects in its turn, as a form of compensation. One example: we're in the Franc Zone. Our operating accounts are managed by the Bank of France in Paris. Who profits from the interest that our money fetches? France.” One thing is certain: the African foreign exchange reserves enable France to pay a small part of its public debt: 0.5% according to Bruno Tinel's calculations. In 2014 the sums deposited in the operating accounts amounted to 6,950 billion FCA francs or 10.6 billion euros.

Growth rates in CFA zone 'lower than other African countries in last ten years'

The worst aspect of the system is that these strict measures imposed on the Franc Zone do not shield it from devaluation, as happened in 1994. In that year, and against the advice of the heads of the African states, Paris devalued the CFA franc by 50 percent.

The backdrop to the devaluation was that for the first time the operating accounts had gone into the red, with the amount of reserves covering the issue of currency in the Franc Zone countries falling below the level of 20% level defined as the minimum threshold. Normally France should have made up the difference but did not do so. “In devaluing, France did not play its role of guarantor,” says economist Kako Nubukpo, the former head of economic analysis and research division at UEMOA and former government minister in Togo. He says that the episode showed that in reality “it's the reserves from the countries of the Franc Zone which have always covered their issue of currency. What France brings is confidence, not something material”.

So in reality Paris, which claims it takes huge risks in committing itself to come to the help of the African central banks when they have exhausted their reserves, overestimates its true role. Economists Francis Kern and Claire Mainguy from the University of Strasbourg also say that one must “put into proportion” the potential impact of deficits in the African operating accounts on France's budget. They write: “In 1993, the only year in which the BEAC [central bank] was in deficit (79 billion CFA francs), this balance represented only 0.58% of the French public deficit (293 billion French francs in 1993). Such percentages cannot raise doubts over France's economic policy objectives. What's more, in this same period the surplus of the BCEAO [the West African central bank] compensated for the BEAC's deficit, and since then the operating accounts of the two central banks have been considerably in surplus.”

In Africa the 1994 devaluation produced a violent shock: the price of imported goods, such as medicines, doubled. On the other hand the operation enabled France to reduce the price of its African imports, while French companies working in the Franc Zone were able to increase their exports. Among the figures behind the devaluation were Nicolas Sarkozy, who was then France's budget minister; Michel Roussin, then French minister of cooperation dealing with former colonies, and now a senior executive of the Bolloré group; Christian Noyer, then director of the Treasury, later governor of the Bank of France; and Alassane Ouattara, an ex-International Monetary Fund official who was then prime minister of the Ivory Coast, of which he is now president. At the time the French government justified the move as a way of boosting the African countries' economies. The prime minister of the period, Édouard Balladur, later said: “The CFA franc was devalued in 1994 at the instigation of France, because we felt it was the best way to help these countries in their development.”

For many economists it is no coincidence that 11 of the 14 African countries in the Franc Zone are today classified as being among the least advanced economies. “The growth rates in the CFA zone have been lower in the last ten years” in relation to other African countries, stated a 2013 report called 'Africa France: a partnership for the future', produced by former French foreign minister Hubert Védrine. The Franc Zone may not be the only factor behind this situation but it has significantly contributed to it.

For a long time the problems caused by the CFA franc were a taboo subject in Africa, but today they are being aired more and more often on television programmes, at public conferences and on social media networks. In France, meanwhile, there have been initiatives to inform decision makers and public opinion about the issue; indeed, one reason why the Franc Zone system has been so rigid for so long is that it has been shrouded in silence. So in 2015 the France-based Gabriel Péri Foundation devoted a symposium on the future of the Franc Zone, while during the national day marking the abolition of slavery on May 10th, 2016, the council of black associations the Conseil Représentatif des Associations Noires de France (CRAN) called for the end of “the CFA franc system”. A collective work, 'Sortir l’Afrique de la Servitude Monétaire' ('Taking Africa out of Monetary Servitude'), overseen by economists Kako Nubukpo, Demba Moussa Dembélé, Bruno Tinel and Martial Ze Belinga, is also due to be published by La Dispute in September 2016.

In addition to making people aware of the issue, opponents of the FCFA are also putting forward alternative solutions. Some economists argue for the creation of national or even regional currencies. Others envisage evolving solutions which would be based on the existing institutions. In 2015 advocates of change organised a petition which called for “the end of fixed and exclusive tying of the Franc Zone to the euro and the introduction of controls over the transferability of capital within this zone”.

One of the ideas suggested by many observers is the introduction of a system of floating exchange to the current FCFA, based on a basket of currencies. Serge Michailof, who used to work for the French development agency the Agence française de développement (AFD) and the World Bank, favours a “rate that can adjust according to events and the international situation”, in order to avoid the CFA franc being overvalued. Such an approach seems even more vital given that fewer and fewer African imports are now coming from Europe. In relation to the rules imposed on the Franc Zone, economist Kako Nubukpo says: “At a minimum there should be more flexibility: the rate of inflation allowed needs to be reviewed and we must define an inflation target according to the rate of growth. The optimal rate for covering the issue of currency also needs to be revised and we should also know on what basis it is determined.”

FCFA depends on events in Eurozone rather than Franc Zone

The defenders of the FCFA, of whom there are more in France than in Africa, insist that it is an opportunity for the countries who use it, that it helps them to build regional economic integration and that it guarantees them good macroeconomic stability. Christian Noyer, who headed the Bank of France between 2003 and 2015, said in 2012: “The last 50 years have shown that the Franc Zone was a favourable factor for development.” But many African economists insist the exact opposite is true, putting forward several reasons, including two main arguments. The first is to do with the tying of the currency to the euro: that makes the FCFA dependant on events in the Eurozone rather than those in the Franc Zone and as a result gives it the same, strong value as the euro, unconnected with the economic context of the countries actually using the currency.

This overvaluation of the FCFA has two consequences, says economist Bruno Tinel: the Franc Zone states, whose economies are among the weakest in the world, do not develop their own industry or modernise their farming as it is cheaper for them to import low-cost manufacturing goods and agricultural produce. On the other hand, their exports are not very competitive. This means the Franc Zone states remain suppliers of untransformed raw materials. As they often produce the same produce as other countries inside the zone, member states trade very little between themselves even though they share the same currency. As a result trade between the region's countries is weak and does not help development. The fact that in the Franc Zone, unlike in the Eurozone, monetary integration preceded economic integration has hardly helped.

The second major reason why the FCFA is an obstacle to development is the way the fixed rate with the euro is maintained at all costs. To ensure this happens the Franc Zone states have very low inflation rate targets imposed on them, close to those of the ECB. Inflation in the UEMOA West African economic area must not exceed 2% while the target set for the CEMAC region of Central Africa is 3%. As a result the national banks ration their loans to businesses. This means that such loans now total just 23% of gross domestic product (GDP) in the Franc Zone, compared with 150% in South Africa and just over 90% in the Eurozone.

“The implementation of limits on monetary financing [editor's note, the direct central bank funding of government expenditure] of the states … creates a strong and healthy constraint for states' budgets,” Christian Noyer has insisted. The problem is that the rates chosen are not adapted to developing economies. “We're subject to the imperatives of the European Central Bank, obsessed by budgetary discipline and the fight against inflation, even though the priority of our under-developed countries should be employment, investment in productive capacity, the creation of infrastructure. That involves a major distribution of loans to the private sector as well as the public sector,” says Senegalese economist Demba Moussa Dembélé.

The economist and former minister for planning and forecasting in Togo, Kako Nubukpo, shares a similar view. “You don't get development without loans, and more inflation would encourage investment. There's a contradiction between talk about development, which calls for major funding, and the FCFA system. Our monetary policies don't take account of the objective of growth,” he told Mediapart. He is saddened to see national banks possessing significant untapped excess liquidity – cash reserves - because of the rationing of lending and the fact that the African member states are obliged to borrow on the international markets at high rates, above those of the BEAC and the BCEAO central banks.

Next: Can African states get rid of the 'colonial' franc currency?

-----------------------------------------------------------------------------

- The French version of this article can be found here.

English version by Michael Streeter