The French authorities in Paris regularly insist they are open to reforms of the Franc Zone, which brings together the 14 African states and former colonies that share the CFA franc currency (see Mediapart's first article on the subject here) which was created 70 years ago. For example, the then-minister for the economy and finances Christine Lagarde said in May 2010: “It's not for France to determine if the current system is appropriate or not, if one should leave it or not. That era is over. It's for the states concerned to take responsibility.” The current minister of finances, Michel Sapin, took a similar line when he said in April 2016: “France's isn't there to decide in the place of the countries concerned. If some ideas, if some proposals are made by the political leaders of the countries concerned, France is obviously open to any change.”

The reality is rather different: France has never envisaged giving up its role as the driving force of the Franc Zone. So when France moved from the franc to the euro in 1999, Paris arranged it so that the rules did not change in relation to the CFA franc. “The adoption of the euro could have resulted in the disappearance of France's power of guardianship over her former colonies, yet France ensured that the monetary co-operation agreements of the Franc Zone were not affected by European integration,” says the France-based non-governmental organization (NGO) Survie, for whom the CFA franc “perpetuates the asymmetrical and neocolonial relations between France and the countries of the CFA zone”. A few years later, in 2002, the French authorities rejected an idea from Charles Banny, the governor of the West African central bank the BCEAO, to remove the word “franc” from CFA bank notes.

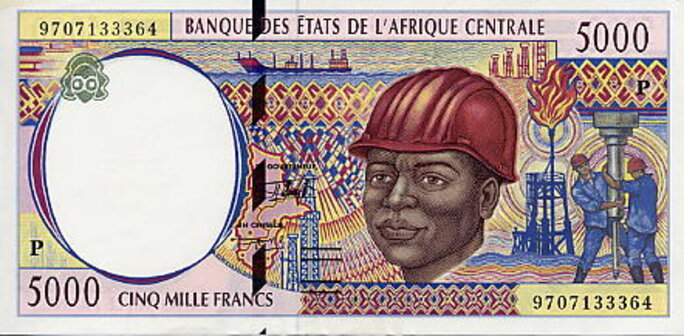

Enlargement : Illustration 1

The CFA franc, or FCFA as it is known in French, has long been a delicate, even taboo issue and the French authorities do not take kindly to criticism of the system. At the start of the 1960s some African heads of state did question it, though as it happens they did not last long in power. Among them was Togo's Sylvanus Olympio (1902 -1963). He became president in 1960 when his country became independent and, wanting to create a national Togolese currency, he sought to review the monetary agreements signed with France. He was assassinated during a coup d'état in 1963. In Burkina Faso President Thomas Sankara, killed in a coup d'état in 1987, was another African leader who wanted to break the economic dependence introduced by Paris. In 1984 he had told the Cameroonian writer Mongo Beti: “The CFA franc, linked to the French monetary system, is a weapon of French domination. The French economy and, therefore, the French market capitalist bourgeoisie, builds its fortune on the backs of our people through this link, this monetary monopoly. That's why Burkina is fighting to put an end to this situation through our people's struggle to build a self-sufficient, independent economy.”

More recently the Ivory Coast economist Mamadou Koulibaly was directly targeted by the French for questioning of the system. When in 2000 he was his country's minister of the economy and finance the French president Jacques Chirac intimated to his Ivory Coast counterpart, Robert Gueï, that the minister should be removed from the government because of his anti-CFA stance. Koulibaly had just opened the campaign for the socialist opposition politician Laurent Gbagbo ahead of the October 2000 presidential election in the Ivory Coast. According to one of the minister's closet aides, Koulibaly had opened it “on the theme of criticism of the fixed and rigid rate of the CFA franc and called for more flexibility and a fluctuating rate, before denouncing the [monetary] cooperation agreements”. However, for domestic political reasons, President Gueï did not in the end remove his minister.

In 2007 Paris was opposed to the nomination as governor of the BCEAO central bank of the Ivory Coast economy minister Paul-Antoine Bohoun Bouabré, Koulibaly's ex-chief of staff. According to journalist Théophile Kouamouo, a keen observer of the period, France did not want Bohoun Bouabré “because he was pro-Gbagbo [editor's note, then president of the Ivory Coast and seen by Paris as an adversary]. His profile as an academic and as a 'non-insider' at the BCEAO was equally worrying: he was liable to suggest reforms that could change everything”. In 2004 Bohoun Bouabré had also sponsored an “international conference on reform of the Franc Zone” in the capital Abidjan. The minister is also credited with having enabled Gbagbo to govern without external financing during a difficult period in terms of security and political problems.

The last senior African figure to be sanctioned over his CFA franc views was Kako Nubukpo, an economist and minister for planning and forecasting in Togo from October 2013 to June 2015. He lost his post under the direct pressure of the BCEAO central bank and of Alassane Ouattara, president of the Ivory Coast. They complained to Togo's president Faure Gnassingbé about Nubukpo's critical analysis of the FCA franc and of the management of the central banks in the Franc Zone. In 2016 the French Treasury was also opposed to Nubukpo's appointment as chairman of the evaluation committee in the French development agency the Agence française de développement (AFD). However, senior officials at the agency nonetheless approved his appointment.

In West Africa Alassane Ouattara, a former official at the International Monetary Fund and former governor of the BCEAO, today plays the role of keeper of the flame and guardian of the current Franc Zone system. His support is essential for the continuation of the FCA franc; on its own the Ivory Coast represents close to a third of the combined economies of the economic and monetary union in West Africa, the UEMOA, which brings together the West African nations who use the CFA franc. Since becoming president in April 2011 Ouattara has shown that the French were right to back him and he remains a safe ally for France's Ministry of Finance. It was he who opened a symposium organised by the French ministry in October 2012 to celebrate the 40th anniversary of the last monetary accords signed between France and the countries of the Franc Zone.

Then in April 2016 Alassane Ouattara sought to call into line African economists who were demanding changes in the CFA franc system. “I was governor of the BCEAO and I am moreover still honorary governor of the BCEAO,” he declared. “And I can tell you that the CFA franc has been well managed by Africans. So I really ask African intellectuals to show some restraint and above all discernment. If one looks over a long period, 25-30 years, this currency has been useful to the people. The countries in the Franc Zone are the countries which have had the most continued growth over a long period, they are the countries which have had the lowest rate of inflation, it's one of those rare zones where the rate of cover of the currency [editor's note, the reserves to back the currency] is almost at 100%. But listen, what else do we want? Perhaps it's the term CFA franc that irritates, but at such a time we can change it. However, on the fundamentals, I consider that our option is the right one.”

Ouattara's attitude contrasts sharply with that of his predecessor Laurent Gbagbo, who was chased from power by France and the United Nations in 2011 and who clearly represented a potential danger for the continuation of the system. Gbagbo's party, the Front Populaire Ivoirien (FPI), has regularly called into question the continued existence of the CFA franc and has demanded complete sovereignty for the Ivory Coast.

The Elysée and French finance ministry on different wavelengths

“While Ouattara is in power the region's heads of state will not adopt positions contrary to his: they are terrified of him,” says one analyst who asked not to be named. “Is it because they think he's all-powerful or is it that in him they hear the voice of France who installed him in the presidency?” the analyst wonders. The fact that several of these regional leaders have themselves come to power after controversial or dubious elections does not help their cause either. “They don't have the necessary legitimacy to engage in a power struggle with France, they can't rely on their populations,” notes the analyst. “So they're trapped. If they were free they'd have criticised the monetary agreements a long time ago. They know it's not them who decide, but France.”

An academic, who also asked not to be named, explained Gabon's situation. “For Gabon's politicians the FCFA is a non-issue: no party or leader has made a speech on it still less made it part of their campaign,” the academic says. “The politicians are all too 'francafricanisé' [editor's note, referring to the close sometimes over-cosy ties between France and its former African colonies] to speak out on this subject. Worse still, the opposition which should raise this kind of issue, simply counts on France to get to power. So, mum's the word!”

Nonetheless, in April 2016 the 'Makya' column in Gabon's newspaper L'Union, a column that generally reflects the views of the country's leaders, showed that the underlying mood is to question the CFA franc. “Let's not forget that for 56 years we have been 'masters' of our own destiny,” it pointed out. “Algeria, Nigeria, Ghana, the Democratic Republic of Congo, South Africa … have been too, and completely, each with their own national currency. Are they doing worse that those from the French sphere of influence whose monetary policy is decided in Paris? Right, it's time to know what we want and where we're heading....”

There has also been one historical example of an African head of state who publicly criticised the CFA franc and yet who did not suffer reprisals as a result. On November 22nd, 1972, during an official visit to his country by French president Georges Pompidou, the president of Togo Gnassingbé Eyadema took France by surprise in publicly criticising the monetary cooperation accords signed between the two countries. A year later the French agreed that the Franc Zone countries could deposit 65% of their foreign exchange reserves with the French Treasury, rather than 100% as had been the case until then.

More recently, two other African leaders have expressed discordant views on the subject too. In April 2010 Abdoulaye Wade, Senegal's head of state, said: “After 50 years of independence, we must review monetary management. If we regain our monetary power we will manage [the currency] better. Ghana has its own money and manages it well; that's also the case with Mauritania, Gambia, who finance their own economies.” But there was no follow up: Wade, whose relations with Paris had become very difficult, left the presidency in 2012 at the end of his second term of office.

Then in August 2015 the president of Chad, Idriss Déby, an old ally of France, added his voice to the debate. “There are some clauses that are out of date,” he said about the agreements governing the CFA franc. “Those clauses have to be reviewed in Africa's interest and also in the interests of France. These clauses drag Africa's economy down.” Déby added: “We must have the courage to say that the moment has come to cut the cord which stops Africa from taking off. This African currency must now really be ours.” However, his words did not lead to any change. In reality, Déby had a serious budgetary problem and for him it was all about putting pressure on the board of the BEAC central bank, of which France is a member, to persuade it to unblock funds.

Déby's remarks did at least have one benefit: they showed that the Elysée and France's Ministry of Finance no longer share the same approach to the CFA franc. Having understood the Chad president's real motives, the French finance ministry quickly dispatched a delegation to the BEAC's headquarters in Yaoundé, to find a solution to Chad's financial difficulties. However, at the Elysée itself, presidential advisors were ready to open discussions around potential improvements that could be made to the CFA franc system. President François Hollande's team certainly seem to have less conservative ideas on the issue than officials at the Ministry of Finance. One presidential advisor, Thomas Melonio, writing in a 2012 report by the left-wing Fondation Jean-Jaurès, described the obligation on Franc Zone countries to deposit 50% of their currency reserves with the French Treasury as “an incongruity which is at the very least surprising fifty years after independence”. He added: “Would those countries whose currency is tied to the euro not benefit from freeing themselves monetarily?”

The stance taken by Hollande's advisors has meanwhile led the president himself to suggest that the African central banks could lower the level of their reserves deposited at the French treasury. “I'm convinced that the Franc Zone countries should be able to handle the active management of their currency and use their reserves more for growth and employment,” Hollande told Senegalese MPs in 2012. However, officials at the French Ministry of Finance seem in no hurry to make Hollande's wishes come true.

A classified document revealed by WikiLeaks highlights the differences that already existed within France over monetary policy involving Africa back in 2009. A senior official from the BEAC central bank told United States diplomats at the time that “technocrats from the French Treasury were relatively progressive in encouraging the francophone governments to be more autonomous, but that the Banque de France continued to exert an outsized influence”.

Even in France itself it is difficult to be critical of the current system. In 1995 the Ministry of Finance reacted badly to a report written by French economist Béatrice Hibou for the French Foreign Ministry's analysis and forecasting centre the Centre d’Analyse et de Prévision (CAP), which was negative about the impact of the CFA franc system and recommended that it be abandoned. The finance ministry protested and demanded a right of reply, while its board of directors in charge of external economic relations asked for the CAP to stop all analysis work on African economies.

Nonetheless, economist and former Togolese minister Kako Nubukpo says he is optimistic. “Inside the French institutions involved one has the impression that more and more people are favourable to changes: they clearly see that the situation of the Franc Zone countries is catastrophic,” he says. Now what remains is to convince the rest of the official apparatus. According to one academic from Central Africa, whatever the obstacles are “we're going to have to get out of this voluntary servitude”. He added: “There will never be genuine independence with a currency controlled by another, whoever it is. Of course there are risks. But it's better to confront them rather than this endless running away.”

See also: Why France still controls ex-African colonies' currency

-------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

- The French version of this article can be found here.

English version by Michael Streeter