Cargèse, a village of just more than 1,300 inhabitants, lies on the western seaboard of the French Mediterranean island of Corsica, known as “the island of beauty” for its stunning scenery, coastlines and wildlife, but also known for its clans, underworld, blood feuds and for having a murder rate well above the average in mainland France.

On March 31st, Mickaël Carboni, who hails from Cargèse, walked free from the law courts in Corsica’s capital town of Ajaccio, where he had been sent for trial along with four other men for the murder of Jean-Michel German, a mechanic who had a past history of small-scale trafficking in cannabis. On September 16th 2016, as German left his home in the suburbs of Ajaccio, he was hit three times in the back by shotgun fire, then executed with one bullet from a handgun.

During the ten-day trial in Ajaccio, the public prosecutor had called for Carboni, who he identified as the leader of the killers of German, to be handed a 25-year jail sentence. But the lawyers for Carboni and his co-accused successfully pointed to the flaws of the investigation, and the jury, after seven hours of deliberations, finally acquitted him and the four other defendants of murder on the grounds of insufficient evidence. The public prosecutor appealed the verdict.

The defendants were however found guilty of receiving the stolen vehicle that was found burnt out close to the scene of the crime, but because of the duration Carboni had already spent in preventive detention he walked out of the court a free man, despite the four-year jail sentence that had been handed to him.

The crime had taken place almost under the noses of the police, who had been watching the movements of the defendants for several weeks as part of an investigation into drugs trafficking. The stolen Citroën C4 vehicle found burnt out close to the scene had even been wired by police to record the conversations of the men, who were arrested the day following German’s murder.

But the police had inexplicably interrupted their surveillance shortly before the killing. The taped recordings proved inaudible except for a few minutes before the C4 was set on fire. The police chief in charge of coordinating the surveillance operation went on sick leave the day he was due to testify in court.

In Cargèse (Carghjese in Corsican), the verdict was met with both surprise and fear. Over a period of almost two years, the village has been blighted by several assassinations and talk of vendetta. One of the victims was Mickaël Carboni’s brother Jean-Antoine Carboni, nicknamed “Tony”, who was murdered on August 12th 2020.

Previously, Cargèse was above all known as a fiefdom of the Corsican nationalist movement demanding independence from France, and is notably the home village of Yvan Colonna, a separatist who was jailed for life for the assassination of Corsica’s prefect Claude Érignac – the highest representative of the French state on the island – on February 6th 1998. But since then, the militant Corsican National Liberation Front, the FLNC, has abandoned armed action, and in Cargèse other forces have taken up their place. “The inhabitants are gripped in fear,” said a police source whose name is withheld. “After the acquittal, nobody now dares to testify about anything at all.”

Contacted by Mediapart by phone, lawyers representing Mickaël Carboni declined to be interviewed.

Early on the morning of September 12th 2019, Massimu Susini, was shot dead as he opened up his seafront café-restaurant on Cargèse’s Peru beach. The 36-year-old was a militant Corsican nationalist; his restaurant was called “1768” in reference to the year when France annexed Corsica, ending the independent republic led by Pasquale Paoli. Susini was hit by several bullets fired by a hidden gunman lying in wait.

The judicial investigation into his killing, led by magistrates in Marseille, has still not concluded on why he was murdered, nor by who. However, those who were close to Susini believe that he was murdered for opposing a local criminal gang, and immediately after the killing an anti-mafia association, the Collectif antimafia Massimu Susini, was created by Susini’s uncle, Jean-Toussaint Plasenzotti.

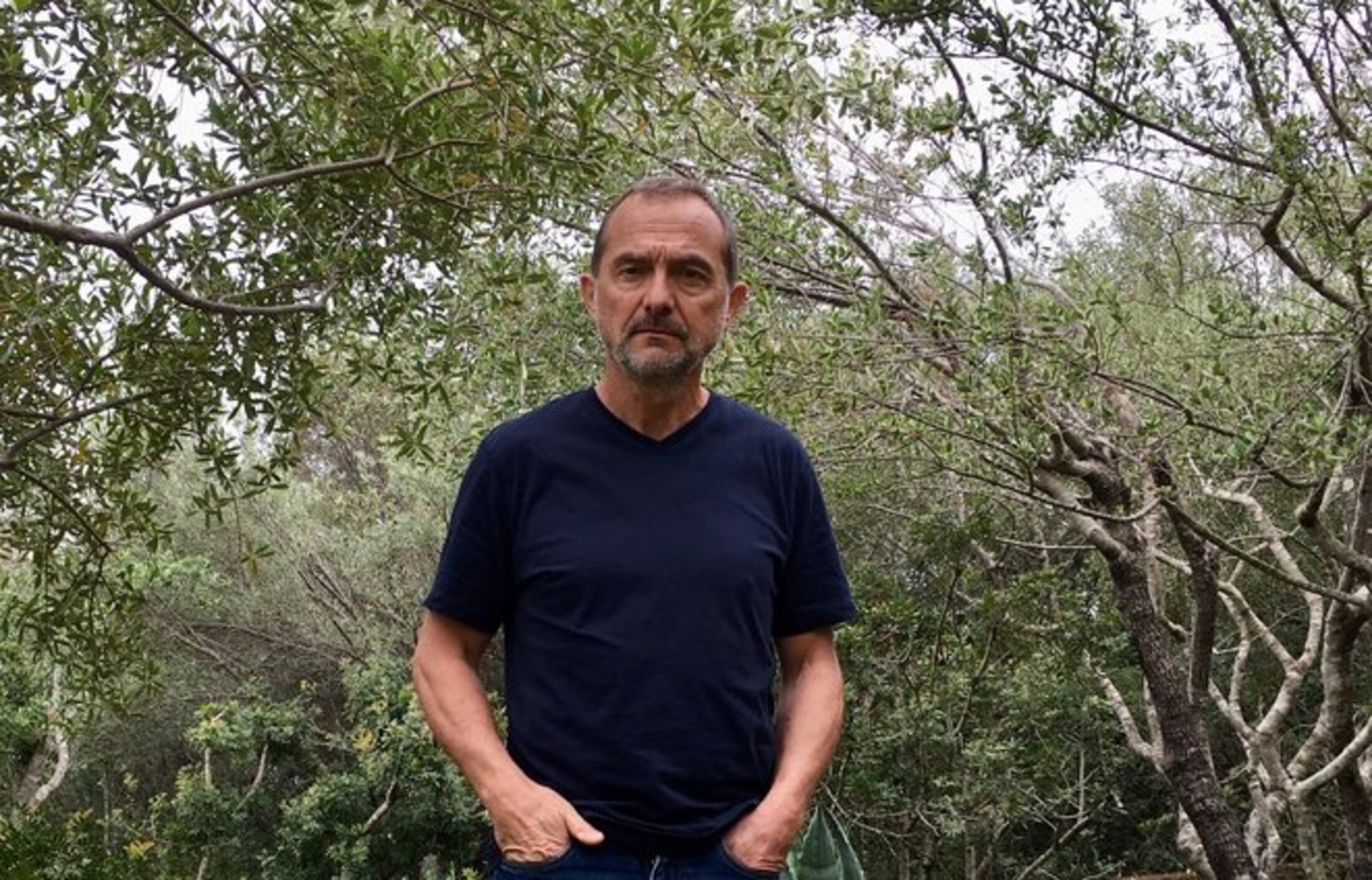

Enlargement : Illustration 1

In its manifesto, presented online in French and in English, the collective denounces the “relative impunity” enjoyed by the criminal groups operating in and around Cargèse. “Massimu verbally and physically opposed such schemes,” it reads. “He put his very skin at stake on the table, and he was aware of it. Without changing his lifestyle, because he refused to yield an inch of ground to the hooligans […] Massimu’s murder aimed at achieving two objectives: clearing the ground for their predation activities and raising fear in order to foster them even more. No one will escape their influence unless we take action now. Those who think they can remain in the shelter of their villa unconcerned by these issues will understand soon, and probably too late, that no one will be left in peace unless they pay the mafia their share. It is merely a question of time.”

In public, Plasenzotti has never named the criminals in question, but in Cargèse most, if not all, know who they are.

Eleven months later, at 4am on August 12th 2020, Tony Carboni, also 36, was leaving a birthday party at Ota, an inland village about 35 kilometres north-east of Cargèse, when he was murdered by several shots from a hunting rifle.

There were no witnesses to the scene, and the case was handed to the same inter-regional judicial investigations unit in Marseille that is in charge of the probe into the murder of Susini. For the time being, there is no firm evidence that the two crimes are connected, and no-one has yet been placed under investigation – a legal move that requires serious and – or – concordant evidence against them.

But the Carboni family issued a statement in which they said that Tony, “profoundly kind” and “very much liked by all”, was “the innocent target of vengeful assassins blinded by hate”. In conclusion, they announced what sounded like a warning of vendetta: “Despite our attempts to bring calm in this deleterious context, an unfortunately irreversible point has been crossed.”

'Silence vies with fear and life has little value'

That announcement was followed by a text published online by the Collectif antimafia Massimu Susini on August 14th 2020, in which it denounced “a statement of death threats targeting the collective and certainly all the people attached to Massimu Susini”.

“We take note,” it added. “[…] The affirmation that a gang of lowlifes was rife in Cargèse, that this gang of lowlifes had links with the mafiosi of the Ajaccio region is a recognised fact, including [as said] by the investigators in private […] No innocent person has been designated and no name has been given. We demand that the police does its job, and that the justice system removes these wicked people from a position to harm.”

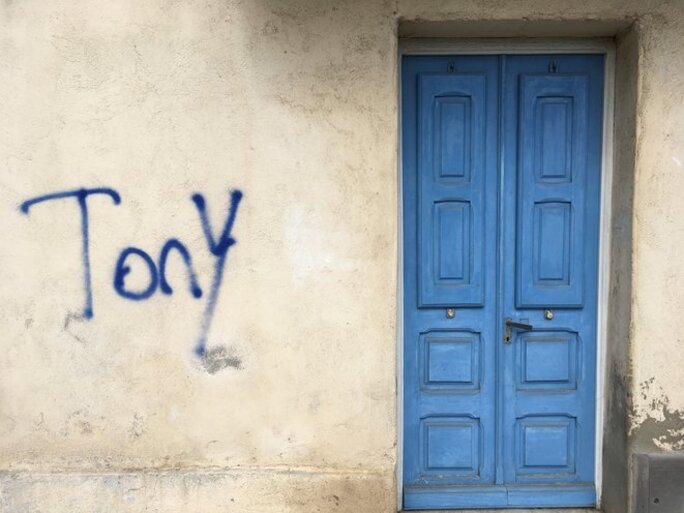

Enlargement : Illustration 2

The walls of several buildings in Cargèse are daubed with tags in memory of the two murdered men.

Enlargement : Illustration 3

Subsequent events were to raise tensions even further.

On the evening of November 17th last year, close to Ajaccio, a mobile patrol of customs officers stopped a vehicle that had been spotted by colleagues one month earlier as it descended from a ferry in the port of the town. This was an armoured Toyota vehicle with a Russian registration plate.

The driver was Louis Carboni, 64, the father of Tony and Mickaël. On the passenger seat was a briefcase in which the customs officers found a loaded .357 Magnum handgun, and in the boot of the car was a bulletproof jacket. Louis Carboni has spent half his life in prison, and his criminal record, notably involving drugs trafficking, includes 17 convictions and a combined total of jail sentences amounting to 50 years.

He was immediately arrested and presented before magistrates in a fast-track court hearing, when he was given a four-year jail sentence for illegal possession of a firearm. During the hearing, he insisted he was not planning a revenge attack for the killing of his son Tony, and that the pistol was intended only for his self-defence. “I was designated by rumour to be the next victim of a settling of scores since my son was assassinated, it was even written in the papers,” he was quoted as saying by the local daily Corse Matin.

On January 4th this year, three men close to the Carboni family were arrested, again near to Ajaccio. They had been under police surveillance since the murder of Tony Carboni. At the time of the arrest, they were travelling variously in a car and on a motorbike, armed and wearing bulletproof jackets, and were believed to be on the point of carrying out a killing.

The Marseille-based inter-regional investigating magistrates were appointed to the case and questioned Louis Carboni, who was by then serving his sentence at the notoriously insalubrious Baumettes prison in the Mediterranean port city. Subsequently, Carboni, the three men arrested on January 4th, and two other people, were placed under investigation for ‘criminal conspiracy to prepare crimes as an organised gang’.

Soon after, on the morning of January 31st, another shooting took place in Cargèse, and which remains officially unexplained. Salah Klai, a 68-year-old retired gardener of Tunisian origin, was hit in the back three times by shotgun fire as he crossed the village square to buy a packet of cigarettes. He collapsed in front of the memorial to locals who died in the two World Wars, and died in hospital four days later.

Why Klai, who lived on a shoestring pension and aid from the charity Secours Populaire, was targeted has baffled villagers. The investigation, based in Ajaccio, has so far found no clues. “The victim was an ordinary person whose life presents no notable clues,” said Ajaccio public prosecutor Carine Greff. “Was he killed by a jealous husband? Was he a mistaken target? We’re looking at every hypothesis.”

The murders over such a short time in and around Cargèse stand out, even in Corsica. According to official figures, between 2018 and 2020, the homicide rate in Corsica, at 0.034 per one thousand inhabitants, was three times greater than the national average, at 0.013 per thousand people. In 2019, there were 13 murders on the island, of which six were regarded by investigators as score settling, and six attempted murders. In 2020, the figures were identical but for an increase in attempted murders, up from six to 21.

Over the first three and a half months of this year – precisely, up until April 16th – there have been five murders, two of them believed to be a settling of scores, and six attempted murders, according to data provided by the office of the official prefectural ‘coordinator of security in Corsica’.

Some regard the unsolved shooting of Salah Klai as part of a deadly atmosphere of criminality that weighs on Cargèse, as elsewhere on the island. In a homage paid to him on March 6th on the village square, organised by the anti-racist group Avà Basta, representatives of Corsica’s two anti-organised crime associations joined in the gathering of around 50 people. One was Dominique Bianconi, a member of the collective Maffia no, a vita iè (Corsican for “Mafia No, Life Yes”). She gave a speech in which she spoke of “the compassion towards the solitude of he who comes from elsewhere to die elsewhere than at his home, by the hand of someone who, as an executioner, placed themselves outside of any humanity.”

“Salah Klai,” she continued, “died in front of the war memorial. […] We who live on this island, we are in a position to understand this pain of brutal death, of barbaric death, of these deaths which are unendingly repeated in the din of bullets and a silence of words, because there reigns here an impunity that favours the installation of a system whereby silence vies with fear and where life has only little value.”

One local source, who asked to remain anonymous out of fear of reprisals, spoke of a more specific hypothesis for the motive of the murder. “The assassination of Salah Klai would have been perpetrated by a group of young people wanting to join a criminal gang, and so in need of proving their capacity to kill by executing an innocent victim,” said the source. Which if true, would also suggest that Klai was not a random target, because killing an Arab rather than a Corsican would not prompt the same reaction among locals. As evidence of this, the tribute paid to him on March 6th was not organised by the inhabitants of Cargèse but by individuals from other regions.

“My intuition, without any precise information but based on my experience, is that the death of Salah Klai was a first test,” said Jean-Toussaint Plasenzotti, uncle of Massimu Susini, and who had attended the gathering in early March. “When someone wants to work for the mafia, he is asked to go and kill someone, just to see if he is capable of doing it.”

Since the murder of his nephew and the creation of his collective, in which he exposes himself by taking a public stand against the criminal gangs, he knows only too well that he is under threat. Plasenzotti limits his travel and was forced to abandon his job as a teacher to avoid being targeted during his commute between Cargèse and his secondary school in Ajaccio – a one-hour, 50-kilometre journey each way – where he taught the Corsican language. One of his sons left Corsica for the French mainland because of the perceived danger.

“Fear is a feeling that permanently accompanies me,” said Plasenzotti. “For particular reasons, but also for more general reasons, because I think we are all in danger, even those who are not busy with anything.”

-------------------------

If you have information of public interest you would like to pass on to Mediapart for investigation you can contact us at this email address: enquete@mediapart.fr. If you wish to send us documents for our scrutiny via our highly secure platform please go to https://www.frenchleaks.fr/ which is presented in both English and French.

-------------------------

- The original French version of this report can be found here.

English version by Graham Tearse