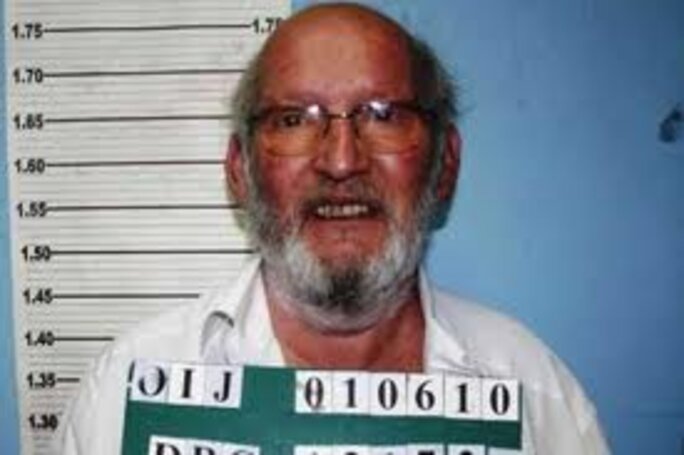

In 2010 the PIP breast implant scandal erupted after the French medical watchdog AFSSAPS discovered that they were being made with a gel that had not been approved for medical use. By the time that Jean-Claude Mas, founder of PIP, and four other executives were convicted in late 2013 for their involvement in the affair, the media had already highlighted the company's many failings, including the way it fiddled safety inspections to hide the poor nature of its products. And last October Mediapart revealed how AFSSAPS itself – now known as the Agence nationale pour la sécurité du médicament (ANSM) – had been slow to react to the problem.

Now Mediapart can disclose that a large number of surgeons who bought and implanted the products for patients were also increasingly aware of the implants' defects well before the scandal came to light publicly. Internal PIP commercial documents from the years 2005 to 2009 seen by this website show that the firm's sales team – who dealt first-hand with clients and were the first to hear complaints – were worried by the growing suspicions of surgeons over the quality of the implants and the gel they contained, and frustrated at the lack of company action to allay those concerns. In particular the documents show that by late 2006 and certainly by early 2007 – three years before the scandal broke - the sales team was seriously concerned about the number of implants that were rupturing. They also reveal that certain surgeons even suspected the company of falsifying its safety inspections in order to conceal the defects. Finally, the sales reports also show that PIP still managed to enjoy the confidence of some key experts in the medical world, and had a close relationship with cancer centres around the country.

- From 2005 there were concerns about a lack of quality and poor management by PIP

In March 2005 the sales personnel at PIP were afraid they were losing an important customer, a Dr Guy-Henri Muller based at Strasbourg in the north-east of France. “Following numerous problems encountered with PIP (extrusions, cases where large amounts of serous fluid formed during reconstructions, shortages of stock) this very big client has let it be understood that he could very soon move to a competitor. This would be very damaging as Dr Muller has a very big reputation,” says a note from one of the sales team.

Meanwhile two other customers protested about the presence of hairs, bubbles, fluff, stains or traces of silicone on the implant shells. Following a complaint by loyal customer Dr Dominique Antz, from Mulhouse in east France, about problems with the texture, a salesperson asked the question: “How can shells with this kind of fault get past quality control?” The same author also regretted the fact that the surgeon had to “open seven boxes of PIP implants...and eliminate 5 ...and put in 2!”

The sales personnel also highlight numerous delivery delays on various products and recurring problems with packaging and labelling. In September 2005 Dr Richard Abs from the Phénicia clinic in Marseille was “very unhappy not to be able to obtain prosthetic bottoms (umpteenth reminder)”. In November 2007 the teaching hospital at Toulouse, the CHU de Toulouse, received “catastrophic deliveries” of inflatable breast implant sizers – designed to give an idea of the correct implant that should finally be fitted – packaged in a chaotic way. “Sometimes they put two of them in a plastic case, sometimes just one. They are sometimes sent in small transparent briefcases with a blue background. The two cases can be used in the same delivery! Sometimes they are sent in cases, in bulk, in cardboard boxes.” In April 2008 a salesperson noted: “Dr Mage has opened a 205 cc [editor's note, the implant's volume] box at the Antoine de Padoue clinic in Bordeaux. Inside, a 470cc!” Less that a year later the same doctor had a similar experience.

In April 2005 there was a problem of a different nature: Dr Alfred Fitoussi, who worked at the Curie Institute and the St Jean-de-Dieu clinic in Paris, “was again asking for his fee concerning a report delivered at a conference in Israel in agreement with the local distributor”. The doctor continued, though, to take part in PIP presentations and workshops even if in February 2006 he was still “very unhappy” about not having been paid.

In a report in May 2005 we also learn that Dr Fitoussi had “withdrawn his request over the real sizes of the asymmetric implants”. These asymmetric implants were an exclusive PIP product aimed mainly at reconstruction surgery for patients operated on for breast cancer. They sometimes produced better results that the normal round implants, but PIP clients often complained that the range of products was too small and did not include enough sizes. Moreover, in certain cases these asymmetric implants became round.

'One day the medical watchdog is going to find this strange'

The reason why Fitoussi had initially asked for the real sizes of these implants is explained in a note from October 2006, which reports an exchange between surgeons during a conference organised by pharmaceutical company Astra Zeneca. One surgeon described how he had chosen a certain model of implant based on the PIP catalogue. “Dr Fitoussi responded that PIP had told him that the dimensions for the implants were false and that the official dimensions were specified for the approval of AFSSAPS without taking into account the real sizes.” This suggests that the catalogue did not give the real sizes for the implants, indicating just how PIP viewed the regulatory side of the industry.

The sales reports talk about several clinical trials on the silicone gel used in the PIP implants. In May 2005 one representative said: “It's now become a matter of urgency to get an update on the clinical trials (silicone gel). Doctors concerned: Dessapt and Muller. The trials began in 2001 and were scheduled for two years! Several requests have been made to the quality assurance department, without success.” Nothing had changed by July. “I am today asking the quality assurance department to find out the situation on clinical trials of the silicone gel in this area (still no response...),” they wrote.

The gel was also studied by Dr Maurice Félix, from the Phénicia clinic in Marseille, one of PIP's biggest customers. In September 2005 Dr Félix had “sent the 'patient monitoring' files concerning the gel trials. Request for settling the account (€305 per file x 29, for a total of €8,845”. This study clearly did not detect the fraudulent composition of the gel. In February 2006 the implant for one of Félix's patients broke and led to siliconoma – inflammation due to the gel – and she threatened legal action. This prompted PIP to pay for all the costs of new treatment. At the start of 2007 Maurice Félix became one of the first to raise questions over the PIP gel, which he judged to be insufficiently “cohesive”.

To keep its clients, Jean-Claude Mas's company gave a certain number of surgeons large discounts or offered lengthy settlement terms. The sales team at PIP complained about the lack of coherence of the company's rates structure and the absence of a scale of tariffs based on quantities ordered. In September 2005 PIP had difficulties with two of its Parisian clients, the brothers Sidney and Jacques Ohana from the Pétrarque clinic. A salesperson complained that the Ohana brothers employed other surgeons on the same preferential rates that PIP had offered them. In the end the matter was sorted out. In January 2008 Dr Sidney Ohana was still a PIP client, but then another incident occurred. While the surgeon was “recording an operation for a television programme, a PIP implant ruptured as it was being implanted...in the end he had to put in a pair of Sebbin implants”.

• From 2006, an increase in the number of PIP implants rupturing

As they were in the front line in dealing with their surgeon clients, the sales personnel were the first to detect the rise in the number of cases of PIP implants rupturing. Often the patients were required to have new operations for which the manufacturer itself picked up the bill. In May 2006 a salesperson wrote: “In view of the more and more frequent cases of the rupturing of gel implants, the explanation that the thickness conforms with the required standard is neither appropriate or justified.” Several surgeons raised cases of broken implants leading to siliconoma.

This trend increased in the following year. In February 2007 a salesperson expressed their fear of a growing mistrust among clients, among whom the idea was “beginning to gain ground” that the ruptures of the PIP implants was due to a fault in the shell. The salesperson feared that some surgeons “I quote, are absolutely convinced they have implanted limited or dubious devices...”

In April 2007 another salesperson wrote: “We are handicapped by the instability of the PIP products. The numerous implant ruptures seriously affect our brand image with plastic surgeons. In the south-west sector a large number of surgeons no longer want to meet PIP.” In June 2007 a surgeon was talking about implant ruptures even though he had not personally experienced one, “proof, if it were needed, that the information passed on in lots of different ways is circulating and that it would in consequence be quite mad to underestimate their impact,” wrote a member of the sales team.

One of his colleagues drove the message home: “For two years I've raised the alarm over the problem with shell ruptures: several emails to management and to the services concerned (quality control, R and D, production). Not once have they replied to me. I think that this year we're going to reach 100 ruptures. It's serious and the consequences could be dramatic for us. Each time there is a DMV [editor's note a déclaration de matériovigilance under which a report of an incident involving a defective product is sent to the medical watchdog as well as the manufacturer]: one day [medical watchdog] AFSSAPS is going to find this strange! More seriously, the surgeons talk among themselves: at a national level they now have a discussion forum via the internet and having been with a client and read an exchange between them: the rumours are rife!! At regional level: the ACPO [editor’s note, group of 45 surgeons in the west of France]: 2 meetings a year, several of my clients have already spoken about it. In short I leave you to imagine the damage...” The concern of the sales force at PIP contrasts with the calmness of the medical watchdog AFSSAPS at this time, who were apparently not surprised by the rise in the number of declarations of incidents.

'My turnover is holding up but for how long?'

At the start of 2008 Professor Jean-Pierre Chavoin, head of service at the teaching hospital at Toulouse, and a PIP client, was nominated as a member of the national committee on medical product safety at AFSSAPS. At about the same period a doctor in his own unit, Dr Dimitri Gangloff, carried out checks on a PIP implant that he was about to use. The implant broke in his hands. An official declaration of the incident was made to the authorities, and the ruptured implant was sent to AFSSAPS. But the agency did not react to this notification, even though it was carried out by someone working for one of its own experts. As for Professor Chavoin, he ended up abandoning PIP implants as his unit had developed a software to carry out made-to-measure implants made by a rival brand Pérouse.

- The alert raised by surgeons in Marseille in 2008

In April 2008 the salesperson who handled the south-east sector of France reported that Dr Félix from the Phénicia clinic in Marseille would not be putting in any more PIP implants until the firm provided “evidence of the improvement of the shells and of our gel (because for him, not only must we resolve the problem of ruptured shells but also that of the gel which, according to him, is not cohesive)”. This surgeon had started to raise questions over the PIP implant's gel since the start of 2007. However that had not stopped the Phénicia clinic from being one of PIP's biggest customers. In October-November 2007 the clinic bought 150 pairs of implants and in 2008 held a stock of PIP implants worth around €50,000.

But incidents of implant ruptures continued among the patients of the three surgeons at the Phénicia clinic, Richard Abs, Maurice Félix and Christian Marinetti, the clinic's main shareholder. Relations between PIP and the clinic grew tense. Dr Marinetti indicated to PIP boss Jean-Claude Mas that he did not want to keep his stock of PIP implants. In May 2008 one of Dr Félix's patients had to have an emergency operation because the doctors feared that she might have metastasis. In fact she was found to be suffering from widespread siliconomas, a recurring effect of the gel.

At the same time Dr Abs suggested setting up a database on incidents linked to the implants, which could be consulted on 'Tam-tam', the internet forum used by plastic surgeons in France. The negative comments about PIP implants grew in number on this forum and the sales personnel became more and more worried. “My turnover is holding up but for how long?” wrote one salesperson in June 2008. Another noted: “My turnover is holding up only because of my relationship with the surgeons.”

In September 2008 Christian Marinetti spoke of a “toxic gel” in relation to the PIP products. He sent an email to AFSSAPS in November of that year, asking the agency to carry out a physical and chemical analysis of the PIP implant gel. But this alert had no more effect that previous ones, including the warning from Jean-Pierre Chavoin.

According to a report in February 2009 Jean-Claude Mas paid €42,000 to buy back Phénicia's stock of implants. The following month Marinetti's colleague Richard Abs met a PIP salesperson. According to that representative Abs “has discovered that there are different qualities of medical silicone and that the costs were considerably lower...these differences (which he was unaware of until now) caused him to have doubts about us, he is asking if the explanation for the great number of siliconomas at each implant rupture does not lie there...and, having doubts, he will not implant PIP any more. I explained to him that we were subject to rigorous inspections, to which he replied that it was possible to show proper files and samples and then to act differently later! And that he would be interested in having a ruptured implant that has caused siliconomas analysed by a laboratory that specialises in this type of research, and not by ourselves. However, he told me that he would not share his suspicions on Tam-tam. The doctor asked that this conversation remain between him and me...”

This report suggests that the Marseille surgeon had strong suspicions that PIP was falsifying its inspections. Then in October 2009 Christian Marinetti sent a recorded delivery letter to the agency's management, without talking about fraud. At the same time AFSSAPS received an anonymous letter, including photographs, which proved the presence at PIP's manufacturing site of products that didn't conform with regulations. However, it was not until March 2010 that the agency decided to carry out an on-the-spot inspection.

- The cancer centre market

In June 2008 PIP won a hard-fought battle for the cancer centre market, or more precisely the 14 cancer centres that had, since the start of 2008, used central purchasing. This unhoped-for success was achieved even though PIP was in the process of losing many customers, was in a dispute with the Phénicia clinic and was the subject of a campaign of denigration on the plastic surgeons' internet forum Tam-tam. It may then, on the face of it, seem curious that these cancer centres, which are supposed to be particularly rigorous in their choice of implants, took on PIP as a supplier. Two factors played an important role in this. For one thing, PIP was the only manufacturer offering 'asymmetric' implants as well as conventional round ones. Secondly, for a long time Jean-Claude Mas's company had had relationships with surgeons working in or who had worked in cancer centres.

'Following certain rumours...'

The asymmetric implants were invented two surgeons, Marie-Christine Missana and Arnaud Rochebilière. Missana worked in France's biggest cancer centre, the Gustave-Roussy Institute (IGR) at Villejuif, Paris, while Rochebilière had a practice at Toulon on France's Mediterranean coast. The invention was patented and PIP regularly paid royalties to the two doctors. According to an accounts document seen by Mediapart these royalties reached €19,700 for each of the inventors in 2005.

In addition, Jean-Claude Mas's firm had maintained close relations with several cancer centres. PIP worked with surgeons who had been at the Curie Institute in Paris, notably Dr Alfred Fitoussi, mentioned earlier, and Dr Krishna Clough, who set up the Institute du Sein – the Paris Breast Centre - in Paris. The sales team's accounts show that Dr Fitoussi had, as noted earlier, carried out presentations and staged workshops for PIP. For example, in respect of a conference held in June 2006 at the Léon-Bérard cancer centre in Lyon, a PIP salesperson noted: “During the conference Dr Fitoussi gave a very good presentation on our asymmetric implants. Professor Chavoin spoke to say that he was fully satisfied with these implants.” And during a seminar on oncoplastic surgery in March 2007, for which PIP funded the buffet, Dr Fitoussi gave a report, as did colleagues from the IGR, Marie-Christine Missana and Lise Barreau. These talks were accompanied by film of operations.

It seems that PIP had some difficulty in gaining a foothold in the Gustave-Roussy Institute, despite the presence there of Dr Missana, who was associated with PIP though her patent. According to the commercial team’s reports, the IGR were at first opposed to the choice of PIP. A report in December 2005 states that DR Missana and Lise Barreau had initially refused to meet the salesperson from PIP, who was only able to present his range of products after the intervention of Arnaud Rochebilière. The go-ahead was finally given in 2006, and by May 2007 the IGR had become the number one client in that geographical sector, ahead even of Dr Sidney Ohana's Pétrarque clinic.

A third cancer centre client for PIP was the Claudius Regaud Institute (ICR) in Toulouse in south-west France. Surgeons at that institute, Ignacio Garrido and Hélène Charitanski, had already worked with PIP. Garrido had led a workshop on the asymmetric implants at a 2006 conference. In addition, Françoise de Crozals, a pharmacist at the ICR, held the key position of coordinator for the cancer centres' central purchasing unit in 2008.

If PIP was successful in the bidding for cancer centre contracts, the situation turned sour at the start of 2009. A report from the commercial team in January of that year noted that the Claudius Regaud Institute “puts in almost no more asymmetrics”, in particular because the implants became deformed and were liable to rotate “as often as anatomically-shaped ones”. By November 2009 Françoise de Crozals, the pharmacist in charge of central purchasing, was beginning to get annoyed. During a meeting with PIP executives she complained that the implant gel was not the same as it had been at the beginning of the deal. Then she sent a letter to the company’s management in which, “following certain rumours”, she asked for the full details of the file comprising “the quality assurance in relation to the origin of the constituent silicone gels of your implants”. In short, there was no longer much trust towards PIP products.

Nonetheless the deal with the cancer centres lasted for more than a year, having been struck at the precise time when a good number of PIP customers were already turning to competitors. This remains one of many anomalies in a tortuous affair of which the judicial process merely scratched the surface.

------------------------------------------------

English version by Michael Streeter