In 2006 Todd Shepard, now an associate professor of history at John Hopkins University in Baltimore, published a book in which he developed a theory explaining the roots of contemporary France – The Invention of Decolonization: The Algerian War and the Remaking of France. His thesis is that France's imperial and colonial history, particularly the conditions under which Algeria wrested its independence from France, shaped the country's modern institutions and continue to affect France today. But Todd Shepard also maintains that the strong presidency and weak parliament that have since characterised the Fifth Republic were not France's only constitutional options. And that the country has turned its back on the distinctive and innovative republican approach to nationality, citizenship and governance seen from 1958 to 1962 during the war of independence. Here he develops his views in an interview with Mediapart.

-------------------------------------------------

Mediapart: How do you analyse the situation in France after the local elections and the government reshuffle?

Todd Shepard: It is a disaster to see someone in the job of prime minister who has celebrated 'whiteness' (1) and rejected the Roma and Islam, as if that were the way to respond to the rise of the Front National and the Right. I was in Marseille just a few weeks ago and I was particularly disturbed by the lack of candidates from immigrant backgrounds in the elections, by the way Samia Ghali was dealt with, and by what [Socialist candidate Patrick] Mennucci said about same-sex marriage having lost votes for the Left (2).

I was also recently in Algeria, and I thought that with the election of Hollande it would at least become possible for France's Algerian side to be recognised, and that people of North African origin would no longer be stigmatised all the time. But even on these issues the socialist government has been disappointing. I want to express my solidarity with you, because the situation in France is very difficult and sometimes desperate. When I talk to my French friends on the phone, I wish them “good luck”.

Mediapart: What are the main stumbling blocks you identify, in French society but also in French politics, given the crisis it is clearly in, as can be seen from the scandals and the hardening of the line among a large section of the Right as well as the powerlessness and disengagement of a broad swathe of the Left?

Enlargement : Illustration 2

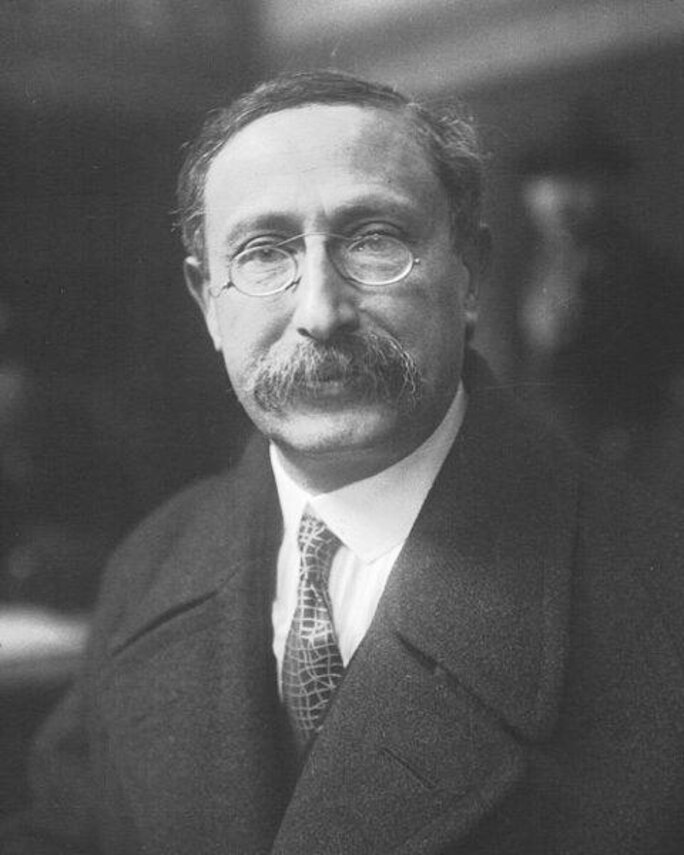

T.S.: For me, the stumbling blocks are linked to having abandoned a progressive perspective, having forgotten entire parts of the French Republic's history, and to France having withdrawn into itself. My personal journey led me to become interested in French history in the 1980s, in the midst of the Reagan period on my side of the Atlantic. I remember being struck by Léon Blum's maxim that even when socialism is not in a position to achieve new social and political advances, it needs to hang on for dear life to the gains it has made.

So I think it is worth preciously guarding some values, some narratives, and even words such as 'socialism' that Manuel Valls wanted to see disappear from the Socialist Party. But I don't think things are hopeless because France has a rich heritage of struggle and integration that can still carry it forward.

What disturbs me most is the intolerance and resentment towards others. This can be explained by a lack of confidence in the future, but it seems to me to be in flagrant contradiction with France's past tradition of integration. France's imperial and colonial history is a history of violence and domination, but also of confronting otherness.

France itself has been changed by wanting to change the idea of 'natives' into 'Gauls'. And I find this negation of a part of the world that has itself become part of France dangerous. To me the situation in France today is deadlocked and threatening because it is out of touch with its progressive republican values, and because the country has forgotten its ability to include 'the other' in its plans.

Mediapart: Your book The Invention of Decolonization: The Algerian War and the Remaking of France lays the blame for much of the dysfunction of the Fifth Republic on the circumstances under which it was brought into being in the middle of the Algerian War. Could you explain?

T.S.: The history of the French Republic has always been linked to its empire. In 1848, 1870 or 1945, when a republic was created the imperial context was a determining factor, and this context impacted the political situation in metropolitan France as well as the ways its institutions were defined. But this was even more the case in the period from 1958 to 1962 when the constitutional architecture and politics of contemporary France were put in place.

France's administrative structure and the nature of the relationships between its executive, judiciary and legislative powers were defined between 1958 and 1962. Electing the president by universal suffrage, which was decided in 1962, and the desire to have a strong executive with a weak legislature, both of these are direct results of the Algerian War and the wish to bring it to an end. The Conseil Constitutionnel (Constitutional Council), which for the first time in French history brought in the possibility for the judiciary to oversee the work of the legislator by verifying whether laws are constitutional, was created in 1958. So this weakening of the legislature's power and the power of Parliament relative to the other powers stems from this period. And we see the consequences today.

This does not just apply to institutions. That period also determined the structure of politics: the centre being attached to the Right; the fear of a new republican front situated to the left of socialists bogged down in their compromises; and the resurgence of a far right even though it had been discredited by collaboration [editor’s note, with the Nazi Occupation].

It was also the time when there was a 'Europeanisation' of how the French population was defined and when the republican promise of citizenship for all was abandoned. Between 1958 and 1962 all Algerians had French nationality, and also full rights as citizens. When Algeria became independent, in order to be able to say that the pieds-noirs [editor's note, French people born in Algeria], who were often of Spanish or Italian origin, would remain full citizens although other Algerians could not lay claim to this, the law was disregarded and instead common usage was invoked, saying that these people were French because they were European.

Enlargement : Illustration 3

We can still see the effects of this way of thinking on the way Arabs are seen as foreigners even when they are French, although it is easily accepted that Italians, Portuguese or Spaniards can become French, as [Spanish-born] Manuel Valls did. So it is no accident that the tensions and deadlocks in France focus on the question of the place of North Africans in French society and their legitimacy in the French imagination, and also on the imbalance between the executive and the legislature. The Fifth Republic was founded on these shaky foundations.

-------------------------------------------------------

1. In June 2009, thinking that his TV microphone was off, Manuel Valls complained about the lack of “whites” as he strolled around a secondhand sale in the streets of Evry, south-west of Paris, where he was mayor and MP at the time. The microphone from French TV station Direct 8, who were following Valls for a programme, heard the Spanish-born politician say “Great image for the town of Evry” before suggesting an aide get him “some Blancs, some Whites, some Blancos”, using the French, English and Spanish words for white people. His remarks caused a row on the Left, though Valls later explained away his comments, telling Direct 8 that he was against “ghettoisation” and that he had simply wanted to portray an image of a town that was more “diverse”.

2. Samia Ghali, a local politician of Algerian origin, failed to win the Socialist Party's nomination as candidate for mayor of Marseille against Patrick Mennucci, an established member of the party’s hierarchy. In March's local elections Mennucci came third, behind the Front National, which won in one arrondissement, and the long-standing right-wing mayor, Jean-Claude Gaudin, who was re-elected.

'Schools, hospitals and universities are being used as weapons against a minority'

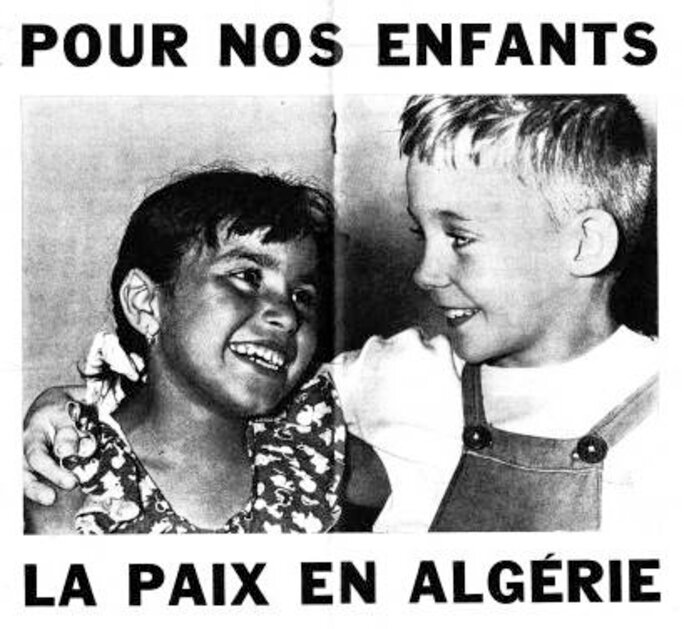

Mediapart: The prolonged exclusion of Algerians from citizenship, even when they were considered French, has led to a very French disconnection between citizenship and nationality. What is implied in France's move from recognising Algerians' struggle by giving them access to full citizenship in 1958 to taking for granted their exclusion and foreignness in 1962?

T.S.: It is a paradox that when you sweep colonial history under the carpet, you conceal not only the violence perpetrated on the imperial dominions but also a period in which republicanism was inventive, when a completely different republican idea was being mooted from that advocated by intransigent, narrow-minded republicans. Before 1958 Algerians had French nationality but they were not citizens, on the pretext that they had a specific civil status called 'Koranic law' for matters such as marriage, the status of family members or inheritance. I looked at this astonishing time between 1958 and 1962 when Algerians were able to become citizens while keeping their civil status as 'Koranic law'. In 1958, then, the principle of a unitary law under the Republic was broken.

It was without doubt an idea that came from less narrow-minded republicans who accepted individual variations, as long as these differences fell within in the spectrum of the republican motto 'Liberty, Equality and Fraternity'. That motto is valid for all citizens, even if they are not all the same. This was a time when the Republic showed itself able to ally universal principles with taking differences into account, instead of pigeon-holing people in distinctive identities in the name of great principles that are not effective, as happens today.

So there we have a turning point at which this inconsistency between nationality and citizenship could have been reduced; an inconsistency that women also suffered from, being excluded from universal suffrage for much longer in the land of 'Human Rights' and the French Revolution than in the United States, for example.

In 1958 the French Republic was seeking ways of moving towards more equality, even if part of the Left and Algerian nationalists found the proposals hypocritical or irrelevant, given the extreme violence that accompanied them and the fact that demands for independence were being ignored.

It was also a time when a policy of positive discrimination aimed at Muslim communities was being implemented in the recruitment of prefects and to the ENA, [editor's note, France's elite school producing top civil servants, politicians and captains of industry] a sort of precursor of an affirmative action policy. Nowadays we think that kind of policy comes from the United States or from abroad, but you just need to look at the history of France to find a time when there was an inventive and creative Republic with a solid base and an openness to change. There was a whole range of political options that the Algerian situation forced people to consider in 1958, and it has been forgotten.

Mediapart: You demonstrate in your work that in its early days the Fifth Republic took its cue from the Algerian War to rein in individual liberties. Are there still traces of this, given that the Sarkozyist right is taking a leaf out of the far right's book on such things, and that the socialists have just chosen as prime minister an interior minister – Manuel Valls - who built his popularity on security issues?

T.S.: Yes, it is still visible, in the law for example. The clearest example is the requirement to carry identity papers that can be checked at any time. This obligation existed at other times in France’s history, but it was re-established in 1962 and continues right up to the present day.

Enlargement : Illustration 5

Another example is that from the French Revolution until 1962, both tradition and the law forbade the police from entering an individual's home after nightfall. That changed after 1962 on the pretext of fighting the OAS [editor's note, the Organisation de l’Armée Secrète, a French paramilitary group that opposed Algerian independence], and also to give the executive the power to apply the Évian Accords [which formally ended the Algerian War], although the archives show that no one thought the threat from the OAS was sufficient to justify this kind of anti-freedom measure.

So from 1962 there was a series of decisions to establish a form of state authority, and we can still see many vestiges of this today. To me it seems foreign to the republican tradition that came from the French Revolution, a tradition that was reinforced many times over before the restrictions related to the Algerian War.

Mediapart: Do you think the importance of the far right in contemporary France has its origins in poor management of both the Algerian War and memory of the colonial period? Isn't it oversimplifying to maintain there is such a continuity?

T.S.: I believe there is one. The far right used the theme of French Algeria to re-establish itself after its defeats in 1945. And in a deeper way, one of its main themes today – that the governing class is lying and only it can unmask this – derives from that time, from the ambiguity of government action, from government refusal to accept responsibility and from the lack of explanation of the consequences of the policies being pursued.

It is easy for the extreme right to say today to a growing section of the French population exactly what it was saying at the time of the pieds-noirs: “You're being badly treated by this Republic, trust us to be more republican that this Republic that is hurting you”, even if that is untrue.

Enlargement : Illustration 6

As it was at the time of the Algerian war of independence, France is today faced with fundamental questions about its political sovereignty and its place in the world, because of neoliberal globalisation and flaws in the European project. And, just as at that time, the extreme right takes advantage of the fertile territory provided by the confusion the government keeps showing on these issues.

Mediapart: The new prime minister is the voice of an uncompromising form of secularism favoured by a section of the Left. How do you read this very French situation?

T.S.: I don't defend an American position on this issue. I admire the history of French secularism because it involved a way of fighting against great powers, notably that of the Catholic Church. But I am appalled that the lessons, principles and the strategies of secularism, developed in a fight against reactionary authorities and enemies of the Republic, should now be used to attack a minority with no real power, namely Muslims, even those who don't practice.

In the past the schools, hospitals and universities were under the control of the enemies of the Republic and the enemies of secularism. Today these places are being used as weapons against a minority. For me the school's mission was to change people and to show them, through education, the advantage of religious neutrality. Today we ask everyone to come into the education system already stripped of beliefs and neutral, at the risk of being excluded from those very institutions that should teach and help people understand the advantages of neutrality. How could we have so forgotten the history of those struggles?

Mediapart: You have worked on the issue of minorities, so what do you think of the relationship that France has with them, whether they be religious, community or sexual minorities?

T.S.: Being homosexual myself, I am horrified when I hear someone such as Patrick Mennucci say that the marriage for all [law] cost votes on the Left, implying in this way that it was Muslims who didn't vote for the Left. I deplore socialists falling into the trap of competing claims of victimhood and setting one minority against another, by depicting Muslims as homophobes.

In the United States, too, it has long been said that Latinos and Blacks were more conservative than the population as a whole. But now that these populations are turning their back on the Republican Party we realise that the 'moral' vote is indistinguishable from a social and political programme. Even people who, because of their religion and their values, could be worried by progressive positions in favour of sexual minorities vote for the Left if the Left has a genuine left-wing political and social programme.

------------------------------------------------------------

The French version of this article can be found here.

English version by Sue Landau

Editing by Michael Streeter