At number 1 avenue Debidour, an apartment building on a small, residential street in north-east Paris, a plaque is affixed to the whitewashed façade. The inscription in French reads: “As of 1940, in this building, France Bloch-Sérazin had set up a laboratory where she prepared explosives for the Resistance. Arrested on May 16th 1942, sentenced to death, transferred to Germany, she was decapitated on February 12th 1943 in Hamburg.”

The story of France Bloch-Sérazin was told in brochures published after France's liberation from German occupation, and was more recently the subject of two documentaries, but it still remains largely unknown today. Now, a biography of her short life has been published in France, and which also presents a rich account of the Resistance movement in the French capital under the 1940-1944 occupation by Germany.

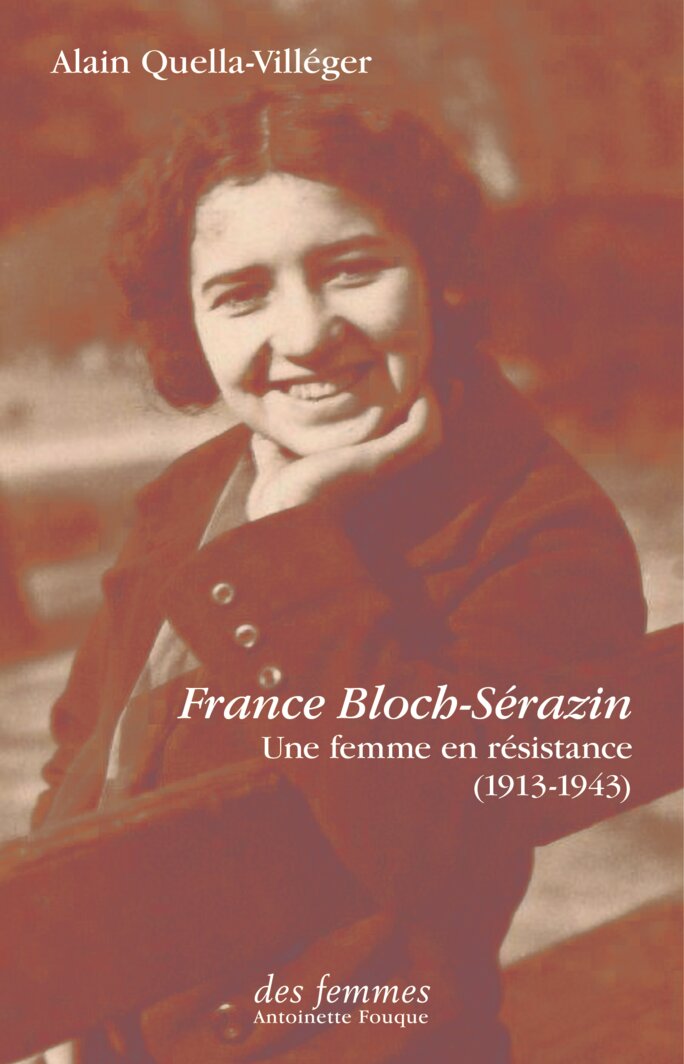

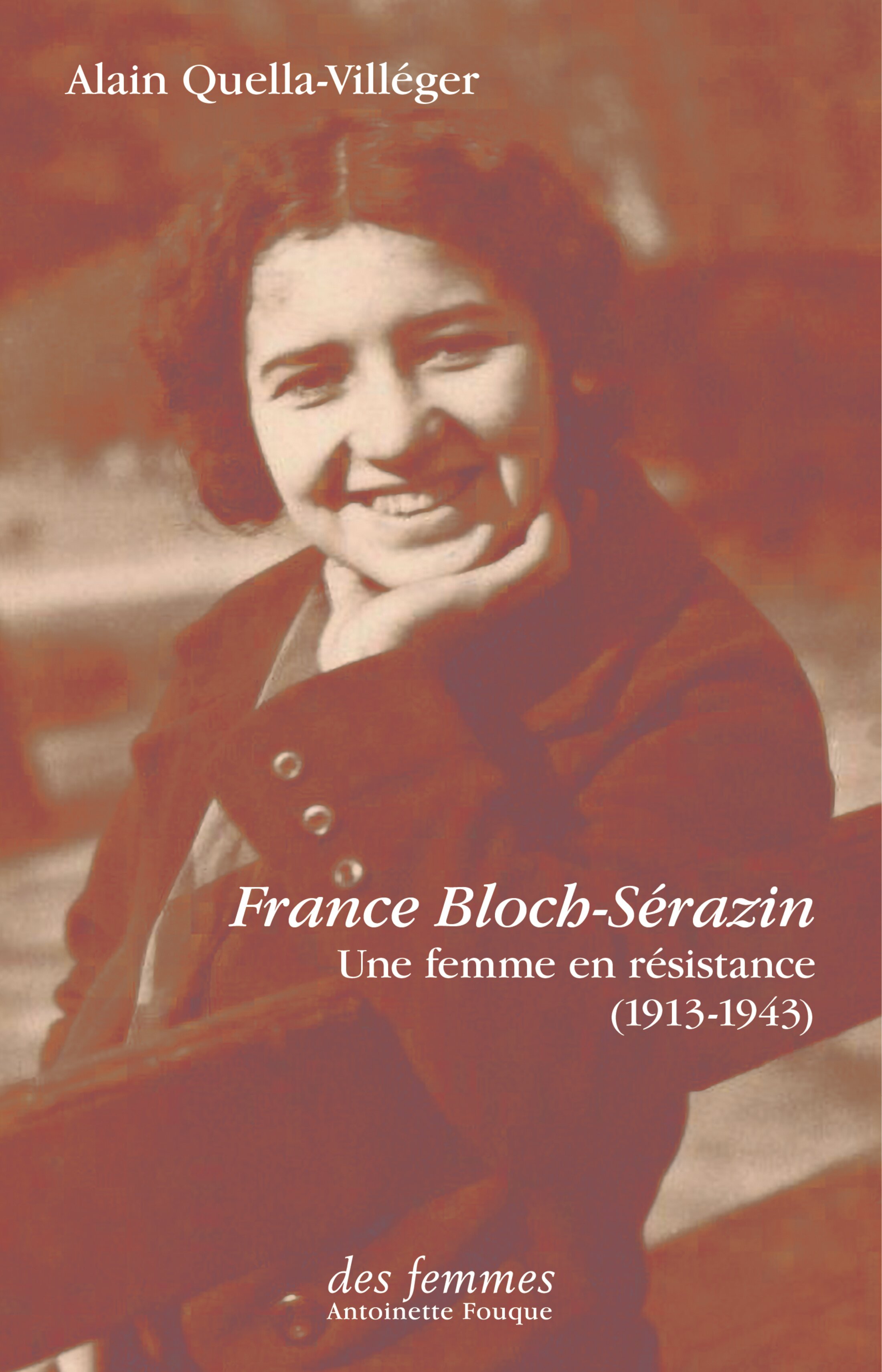

In France Bloch-Sérazin – Une femme en résistance (1913-1943), historian Alain Quella-Villéger tells a moving story that is all the more compelling because of the precision of his historical research. Leaving behind the rhetoric of the “shadow” army, the historian fully succeeds in presenting the strength of the determination of those who joined the Resistance movement, and the heroic normality of their existence.

France Bloch-Sérazin was born on February 21st 1913 into a French middle-class family of intellectuals. Her Jewish father was the writer Jean-Richard Bloch, the joint editorial director of a daily newspaper called Ce soir, and a member of the editorial board of the review Europe. Her mother, Marguerite Herzog, was the sister of Émile Salomon Wilhelm Herzog, better known as the novelist and essayist under the pen name André Maurois.

France emerged from schooling with both an arts baccalauréat, and another,which she passed one year later, in sciences. She took up a job as a researcher at the Paris Higher National School of Physics and Chemistry, in the Latin Quarter of the French capital. After the establishment of France’s collaborationist Vichy regime, following the German occupation of France, she was dismissed from her post in 1940 as a consequence of the new laws targeting Jews that were introduced by Vichy.

Enlargement : Illustration 1

As a schoolgirl she dedicated a notebook to quotations, and which included that of the 19th-century British prime minister Benjamin Disraeli which began, “Life is too short to be little” (and which continued, “Man is never so manly as when he feels deeply, acts boldly, and expresses himself with frankness and with fervour”), perhaps a touch grandiloquent for the statesman who died in old age but sadly relevant for France, a Resistance heroine who was guillotined by the Nazis one week before her 30th birthday.

Like many people who joined the Resistance, France Bloch-Sérazin entered the clandestine networks because she was continuing, with different means, a combat that she had begun a few years earlier. Her friends remembered her as someone who fervently pursued ideals of justice, and who “could not allow the slightest divergence between thought and action”. She joined the French Communist Party in 1936, drawn to the political movement by the positions of her family, and notably her father, who was also a Communist politician and militant anti-fascist. France Bloch-Sérazin deplored the fact that France did not intervene in the 1936-1939 Spanish Civil War alongside the Republicans, denounced the 1938 Munich Agreement with Germany, and when the Communist Party was dissolved by French prime minister Édouard Daladier at the outbreak of World War II in September 1939 she chose to continue her political activity in clandestinity.

She shared her political engagement and actions with her husband, Frédéric Sérazin, better known as Frédo, a metal turner and Communist trade union official. She had first met Frédo at the Communist Party’s branch in the 14th arrondissement of southern Paris, and the couple married in May 1939. They spent only a short while together before Frédo was called up to serve in the army. After the debacle of France's defeat, Frédo was a member of the Communist “Youth batallions” which fought against the German occupation, and was later arrested and successively placed in various internment camps. After escaping one of them for a second time, he was again arrested, in June 1944, but this time tortured and killed by the Gestapo in the town of Saint-Étienne, in central France.

France and Frédo had a son, Roland, born in January 1940. Roland still has a toy his father made for him and managed to send to him during those dark years of the war. France looked after Roland while keeping down her new job and serving the Resistance network, and also visiting, when possible, her imprisoned husband. Before she in turn was arrested, she managed to place Roland in the care of a cleaning lady who hid him from the authorities, thus avoiding the possibility that the child could be used by the police to force her to talk.

In 1941, France was a member of the “Francs-tireurs populaires” (FTP) branch of the Resistance movement in Paris, under Raymond Losserand – who would later be arrested at the same time as her and shot by firing squad in May 1942. At one point, she managed to meet up with Frédo after he escaped, for the first time, from an internment camp (he would be quickly re-arrested). “Claudia”, her pseudonym in the Resistance, wrote and distributed leaflets, and pasted posters on walls at night. For Bastille Day on July 14th 1941, she secretly placed little paper models of the French tricolour flag around the 14th arrondissement. But above all, using her expertise in chemistry, she produced explosives in a clandestine lab at number 1, avenue Debidour, to be used for sabotage operations. France escaped arrest when the lab was raided in November 1941, and set up new quarters elsewhere in the capital. But her cover had been blown, and she was now actively hunted by the police.

All she could leave loved ones was a small hairpin

Archives from the “Brigade spéciale” of the police intelligence services of the time reveal their report on France, described as “a terrorist” – the regular description for Resistance members. “Sérazin Françoise” it reads, using the common French administrative habit of identifying a person by their family name first. “Born Bloch. Of Jewish faith, living at 1 rue de Monticelli (14th), an active Communist militant. 1m58, about 20-years-old, graceful face, dark-coloured eyes, light chestnut-coloured hair. Speaks French with a stylish accent, of a student or Bohemian type, neatly clothed.”

Knowing she was being hunted, France went underground, variously leaving and returning to Paris, while planning an attempt to free her husband from internment camp. She continued to work as a Resistance liaison agent, but on May 16th 1942, “Claudia” failed to appear at a secret rendezvous with one of her comrades. That morning she had been arrested along with dozens of other FTP members as part of a vast roundup organised across France by the Vichy authorities. She was first placed in La Santé prison in Paris; as of June, letters she was initially allowed to receive were sent back to their senders with the cynical official explanation, “Left without a forwarding address”.

Enlargement : Illustration 2

After interrogation by the Gestapo, she was tried by a German military tribunal, along with 22 members of her Paris Resistance group, in a procedure which was called Nacht und Nebel (“night and fog”), defined by a 1941 decree that ordered such trials to be held “behind closed doors and in the utmost secrecy”. As a result, there are no documents that give an account of the trial, which was held at the Continental hotel in Paris and which ended with all the accused, with the exception of France Bloch- Sérazin, being sentenced to death.

However, in German military archives in Potsdam, a document marked “secret” lists the names those who were ordered to be shot for collaborating with “the enemy”. The list includes, “Raymond Losserand, furrier; Marie Besseyre, painter; Gaston Carré, plumber; Henri Douillot, locksmith; André Faure, metal worker; Lucien Micaud, riveter; Édouard Larat, boilermaker; Françoise Sérazin née Bloch, chemist”.

But France was allowed an appeal for pardon, and was transferred to several successive prisons in Germany while awaiting the outcome – which was in little doubt. It is mostly through the accounts of fellow prisoners that her final months of existence can be traced – with one notable exception; the woman director of the Hamburg prison where France spent the last two days before her execution. Friede Sommer appears to have been particularly moved by the fate of France and promised the young woman that she would ensure that the letters she wrote to her family and husband would reach them. Both women knew that, under the strict rules of the Nacht und Nebel procedure, without Sommer’s intervention, nothing France wrote would ever leave the prison.

On February 12th 1943, France Bloch-Sérazin was finally executed by guillotine in a German prison courtyard.

Sommer held good to her promise, recopying the letters and hiding them until the end of the war. Alain Quella-Villéger’s biography begins with extracts from France’s letters of adieux. Those she wrote for her husband would never reach him because of his execution in 1944. The letters, describing her love for those close to her, her love of life and her just combat, were joined with the only object she could leave them – a small hairpin.

Quella-Villéger’s France Bloch-Sérazin – Une femme en résistance (1913-1943) revives all the raw emotion and importance of a story that 70 years of political, pedagogic and cultural memorial could have numbed. Through its very knowledgeable account of the history of period, and by the inclusion of pertinent witness accounts, photographs, letters, police and interrogation records, the biography offers a new perspective to what was the Communist Resistance movement and the engagement of its members. The fascinating documentary aspect of the work is indissociable from the reflection it inspires into the heroism of women, a virtue often subordinated in popular imagination with regard to their greater duty towards parents, husbands or children.

France Bloch-Sérazin had a family, husband and child who, it appears, she had an immense love for, and which they knew. Her personal engagement, her life and her death are brought back in all that is evident, but also in a certain aspect of mystery. Quella-Villéger succeeds in combining the rigour of scientific research with the delicate evocation of a woman of outstanding and tranquil courage, a person with no vanity or arrogance, who remained true to what she wanted to be.

-------------------------

- This article by Claude Grimal is published simultaneously by Mediapart and the independent online French review of literature and art, En attendant Nadeau, as part of an editorial partnerhip between the two. The original French version can be found here.

Enlargement : Illustration 3

France Bloch-Sérazin – Une femme en résistance (1913-1943) by Alain Quella-Villéger is published in France by éditions Les femmes, priced 18 euros.