The number of words contained in an obituary is, of course, no tool of measure of those who have passed away. But the brevity of some tributes highlight the unease that the glorious dead can cause among the far-from-glorious living.

The announcement earlier this month of the death of 97 year-old Raymond Aubrac, a heroic figure of the French Resistance movement, was followed by a short, 120-word communiqué from the French presidential office. That was just half of what was written in the Elysée Palace communiqué about film director Claude Miller, and just a third of what was contained in its tribute to the Paris Political Sciences School director Richard Descoings, who both also died in April.

But there is nothing surprising in this, at least if one supposes that Aubrac’s public support for Socialist Party presidential candidate François Hollande was not the only explanation for the meanness of the communiqué. In his life and the causes he espoused, by his convictions and his loyalties, Raymond Aubrac (click here for a detailed obituary) was quite the opposite of the national degradation incarnated by the current French presidency. This was true right to his very manner of being, a man whose approach was a mix of discretion, irony, curiosity, acuteness and subtlety.

In 2009, the path of the man who co-founded the major wartime Resistance movement Libération-Sud indirectly crossed that of Nicolas Sarkozy, when he attended the third annual meeting of the association Citoyens résistants d’hier et d’aujourd’hui (Resistant citizens of yesterday and today). The association was created in 2007 in outraged response to Sarkozy’s political misappropriation of the memory of the heroic combat led against the German army in the French Alps by the Resistance group the Maquis des Glières.

Aubrac was joined at the event by another celebrated French Resistance veteran, Stephen Hessel. The pair were there not only on behalf of the causes they had both espoused throughout their lives, but also because they were among those who initiated the 2004 Appel des résistants (‘Appeal of Resistants’). That appeal was launched on the 60th anniversary of the presentation of the programme of the National Council of the Resistance in defence of the policies of national solidarity the Council proposed. These included the creation of the social security welfare system, the right to a proper retirement pension, freedom of the press and the right of access for all to education and culture. The 2004 appeal underlined its opposition to “the current international dictatorship of financial markets which threaten peace and democracy”.

It was this chain of stable and coherent beliefs, joining the present from such a full past, that led Stephen Hessel to publish what became his international best-selling essay, Time for Outrage (originally titled Indignez-vous !), and which drew from a speech by Hessel at the mountain table of the Plateau des Glières.

In his speech before the 2009 annual meeting of the Citoyens résistants d’hier et d’aujourd’hui, Raymond Aubrac spoke of the necessity for unity and the need “not only for a common programme, but also common projects”.

“There lies one of the greatest shortcomings of our time and of our country,” he warned. “We don’t know where we are heading, in a world that is more and more complex. We need these projects, by respect for those who fought so that this promise of the future be elaborated. We also need this optimism shared by all members of the Resistance, without exception, as they advanced towards their goal; more liberty, more equality, more fraternity.”

The importance of optimism

For Aubrac, optimism was a key notion, a value to be cultivated and a principle to be transmitted, especially towards the young. It was an element of the mind that provides the energy for reaction, for acts of resistance that transform themselves into creations.

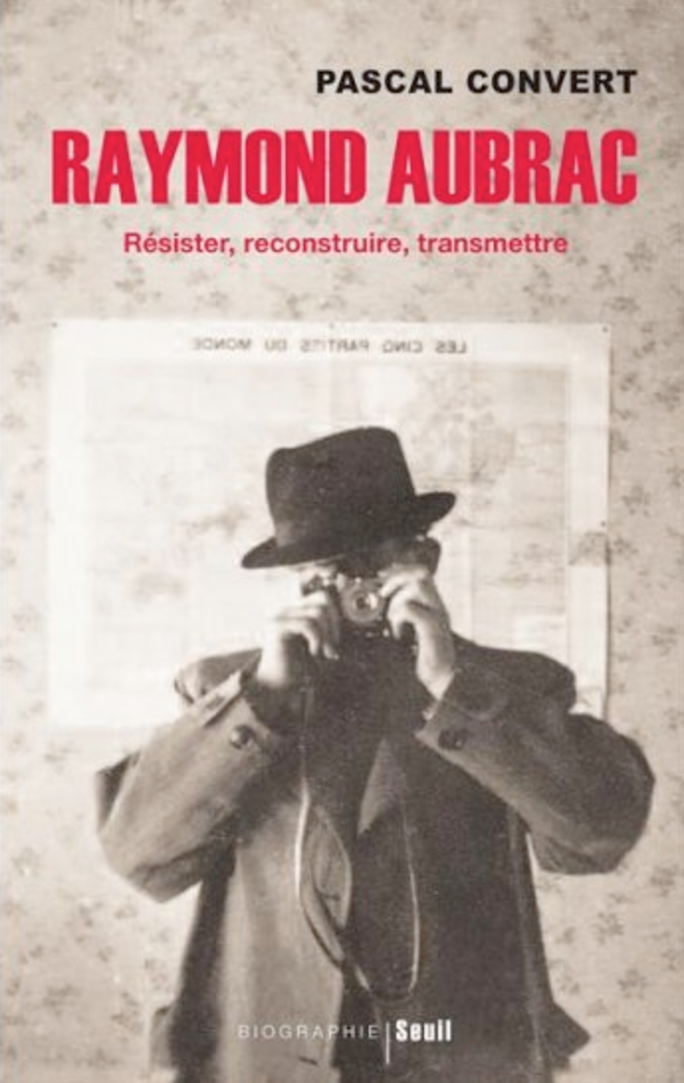

Quoted in a biography of him published last year by Pascal Convert, Raymond Aubrac. Résister, reconstruire, transmettre, Aubrac insisted: “One must be optimistic, it is that which is the spirit of the Resistance. All the people who engaged in the Resistance or with General de Gaulle, they are optimists, people who don’t give up, who are convinced that what they will do will serve a purpose. You must be confident in yourself, be optimistic and believe that these battles are useful.”

His refrain was already present in his own autobiography, Où la mémoire s’attarde, published in 1996, and notably in a book, published last year, of conversation and debate with his grandson, Renaud Helfer-Aubrac, who served in the French military during the conflicts in the former Yugoslavia and in Afghanistan. In that book, Passage de témoin, Helfer-Aubrac discusses with his grandfather the subject of personal engagement, beyond the political notion, in the sense of defiance, risk and daring. “Mathematically, audacity would be the sum of optimism and courage?” he asks Aubrac. “Exactly,” the elder replies, before then carefully detailing what he meant by optimism.

“An optimist,” Aubrac explains, “is not a satisfied individual, happy with the current situation. It is someone who thinks he can do something that will serve something. That’s what I explain to kids when I speak about the Resistance to them. De Gaulle was optimistic on June 18th. All those who entered the Resistance were optimists. In fact,‘optimistic’ is not the right word. It is more like ‘active hope’. But the word ‘hope’ has a religious connotation that only half pleases me. Priests talk all the time about hope and love. So let’s come back, without anything better to hand, to the word ‘optimism’. I say again, de Gaulle was optimistic when he said ‘We have lost a battle, but we haven’t lost the war’. It is therefore not surprising that the programme of the Resistance was a concentration of optimism, placed into being by an optimist called de Gaulle.”

This insistence about optimism was a life lesson. In an epigraph to his biography of Aubrac, Pascal Convert cites a phrase from 17th-century philosopher Baruch Spinoza’s work Ethics, in his ‘Proposition 67’: “A free man thinks of death least of all things; and his wisdom is a meditation not of death but of life.” Convert, a sculptor who notably created the monument that stands on the Mont Valérien memorial site close to Paris in commemoration of those executed there by the Germans, defines his own path of creation as an “archeology of architecture, of infancy, of history, of the body”. The present is what archeologists always exhume: a present past, the past in the present, what is present from the past.

In Raymond Aubrac’s meditation on life with Convert, an unhurried and flowing conversation, optimism figures not as a past message but, rather, as a value for today. It is an invitation to shake out of our torpor, to throw off our resignation or worry; to refuse fear, and to fight those who cultivate it and maintain it and exploit it; to step out of our closed boundaries, to cross limits and frontiers. His interest in the world and the lives of others is another example of the total incompatibility between the life of this Resistance fighter of yesterday and today with everything that represents the current French presidency – and which, let us hope, is about to come to an end.

Aubrac, whose heroic late wife and former Resistance fighter Lucie was an integral part of his being, was not only a former wartime hero. He was also, if not above all, a man concerned by the affairs of the world, driven by an untiring curiosity for its peoples, civilizations and cultures. That is clearly revealed in Pascal Convert’s biography, the jacket of which is illustrated with a photographic self-portrait by Aubrac (see above left), taken in 1940 in front of a mirror in which is reflected a map entitled ‘The five parts of the world’.

A bridge-builder by profession and conviction

Raymond and Lucie Aubrac ceaselessly toured the world, from the US to the then-Soviet block countries of Eastern Europe, from Morocco to China. Not forgetting Vietnam, where he met Ho Chi Minh in August 1946, and which led him, during the 1970s, into a successful secret diplomatic mission with the Americans to seek an end to the war in South-East Asia. Aubrac had studied in the US during the 1930s where, Convert writes in his biography, he was enthused by the understanding “that only he who migrates leaves behind [the issues of] identity”.

If he had had but one compass, it could have been that of international fraternity, the belief in a common humanity over and above origins, identities and adherences. That conviction also explains both his relationship with the communist movement – not withstanding his criticisms of it and the distance he kept from it – and his professional path as an international civil servant, beginning as director of the United Nations’ Rome-based Food and Agriculture organization, and subsequently as an organizer of cooperation projects at UNESCO.

“Raymond Aubrac was a traveler of the 20th century,” concluded Convert in his biography. Commenting a photo of double self-portraits of Raymond and Lucie, taken in 1940 shortly before the couple entered into clandestine resistance, Convert comments: “The faces of Raymond and Lucie Aubrac, entirely masked by the camera, undo the issue of identity.” Born by the name Raymond Samuel to a Jewish family from the town of Vesoul, in eastern France, Aubrac forgot none of the injurious use of identity by successive waves of anti-Semitism, racism and xenophobia. But he always doggedly rebuffed them and busied himself with building bridges above confrontation.

Indeed, building bridges was the first professional activity of Aubrac, an engineer by training. An opponent of any form of sectarianism, he saw a profound significance in bridge-building - linking opposite river banks, establishing relations, creating exchanges and circulation – as he explained to Convert. “Bridges in Ancient times were built by pontiffs. That means that there is something magic, after all. It’s true that to build a bridge, one needs the confidence of those between whom you are going to establish a link. They must know you, you must know them. How that happens, I don’t know. No-one can define it. Generally, people become pontiffs because they built bridges that lasted. It’s as simple as that. […] I always try to understand what are these two territories that one wants to link. What are the problems, why is there an obstacle, what can one suggest to get over the obstacle? It either works or it doesn’t. But one needs to employ a certain amount of patience, it’s generally very long. It can take a lifetime. You must try to obtain confidence and, above all, to keep that confidence. You must not try to trick reality, and engineers know this rule. […] One must try to understand what is real, to accept it, and not try to forget it.”

It is for us to follow along the path of this man who, Convert wrote in his biography, believed in “better helping his country by establishing bridges with other countries, with other cultures, rather than adding his voice to those, already too many, believe they are performing an act of patriotism in their lamentations about a France relegated to a second role […] They, the nationalists, the sovereigntists and the xenophobes always ready to reject foreigners, illegals, the young from deprived and ethnically mixed neighbourhoods [1], and all the young, he fights them relentlessly.”

- Edwy Plenel is Editor-in-Chief, and a co-founder, of Mediapart, and was formerly editor of French daily Le Monde.

-------------------------

1: Referred to as "banlieues", literally meaning suburbs, in the original French text. The word banlieue is now synonymous with high-rise, low income neighbourhoods that ring France's urban cities, where often higher-than-average unemployment blights largely disenfranchised populations of youths from mixed ethnic backgrounds.

English version: Graham Tearse