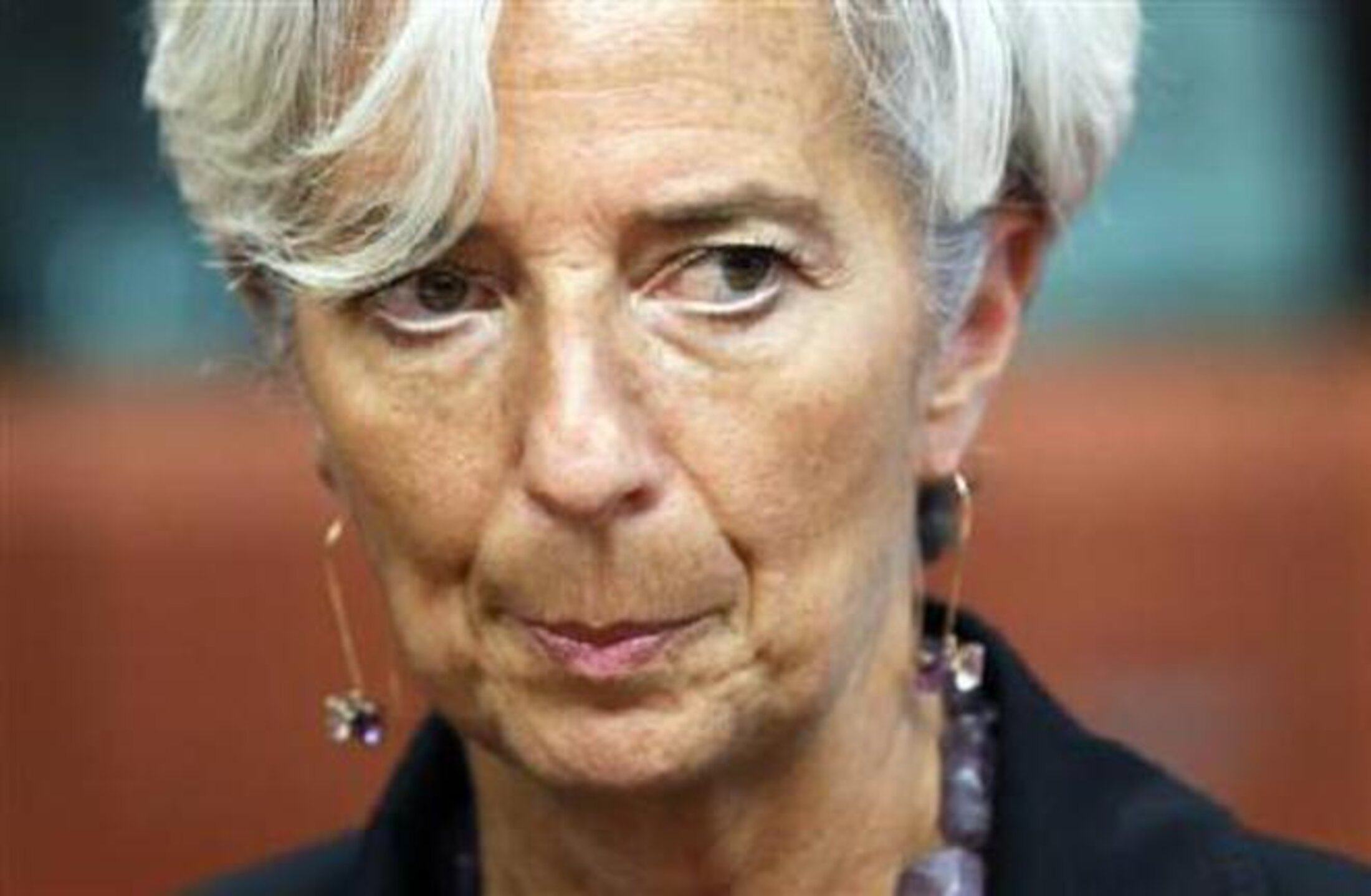

International Monetary Fund (IMF) managing director Christine Lagarde is to be tried by France’s Court of Justice of the Republic on the charge of “negligence by a person in position of public authority” over her role, as French finance minister, in the awarding of more than 400 million euros of public funds to French tycoon Bernard Tapie in 2008, Mediapart has learned.

The charge carries a maximum sentence of one year in prison and a fine of 15,000 euros.

The move comes just three months after senior French public prosecutor Jean-Claude Marin in September recommended charges should not be brought against the IMF chief. Lagarde, 59, succeeded Dominique Strauss-Kahn as head of the IMF in 2011 after he was forced to stand down over a sex scandal.

After news of the story broke, Lagarde issued a statement in which she said she would be appealing to France's top appeal court, the Cour de Cassation, in the light of the “difficult to understand” decision to send her for trial.

The statement issued on behalf of the former minister said that she had “always acted in this affair in the interests of the state and with respect for the law. She considers, like the prosecution authorities at the Cour de Cassation, that there is no evidence that can be imputed to her”. The statement said Lagarde would be informing the IMF board of directors “about this latest development in the case”. Lagarde’s lawyer Yves Repiquet told French TV channel iTele that the decsion to make her stand trial was “incomprehensible”. IMF spokesman Gerry Rice said the organisation “continues to express its confidence in the managing director's ability to effectively carry out her duties”. He added: “The Board will continue to be briefed on this matter.”

Lagarde also received some backing from the French governement. “She's innocent until proven guilty, so I don't see how this should prevent her from carrying out her current duties,” finance minister Michel Sapin told reporters while in New York.

Enlargement : Illustration 1

The Court of Justice of the Republic (CJR) is a special court designated to investigate suspected malpractice by government members in the course of their duties, and to also judge them if charges are brought. The verdict in Lagarde’s trial will be decided by a judging committee made up mostly of French Members of Parliament.

The decision by a CJR panel of three magistrates to send Lagarde for trial, rejecting Marin’s recommendation, follows a more than four-year probe by the court’s investigating commission, which also revealed conflicts of interest among members of the arbitration panel.

The commission finally placed her under investigation in August 2014 (a French legal status that is one step short of being charged), along with five others including Tapie and the CEO of French telecommunications giant Orange, Stéphane Richard, who served as Lagarde’s chief of staff when she was finance minister.

There is no suggestion that Lagarde benefited personally from any decision she made, and she has always denied any wrongdoing.

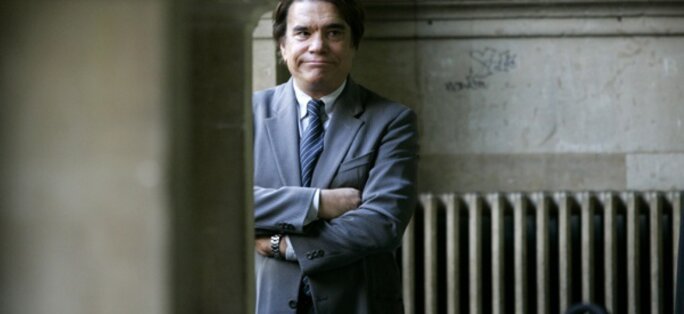

Tapie, 72, was ordered by the Paris appeals court on December 3rd to pay back to the French state the 404 million euros awarded to him by a panel of private arbitrators seven years ago. That award ended a longstanding legal battle until then played out in courts of law. The case centred on Tapie's alleged spoliation by the former state-owned bank Crédit Lyonnais during its mandated sell-off of Tapie's business interests, notably his controlling share of the Adidas sportswear and accessory company, in the early 1990s.

The appeals court ruling on December 3rd found that Tapie had not been defrauded by the Crédit Lyonnais.

The lengthy legal battle that opposed Tapie and the French state - in the form of the public agency responsible for managing the liabilities of the now-defunct Crédit Lyonnais, the Consortium de Réalisation (CDR) – began more than 20 years ago, after the Crédit Lyonnais collapsed following a high-risk lending scandal in 1993.

Shortly after the election of Nicolas Sarkozy as president in 2007, his first finance minister, Jean-Louis Borloo, a close friend of Tapie for whom he once served as a lawyer, took the decision of removing the ongoing case from the courts and placed it into private arbitration, a move that gave Tapie a significantly greater chance of winning a payout.

One month later, in June 2007, Borloo, a close friend and former lawyer of Tapie’s, was moved to another ministry and replaced by Lagarde who pursued Borloo’s controversial decision, one made all the more questionable because Tapie, a flamboyant tycoon and former centre-left politician, was also a friend of Sarkozy’s, and gave public support to the latter’s 2007 election campaign.

In September 2007 Lagarde gave written instructions to senior civil servants to start the arbitration process. In July 2008 she signed instructions ordering the same civil servants not to appeal against the 404 million-euro award given by the arbitration process, and which included 40 million euros in damages.

In her several statements given to the investigating magistrates of the CJR since she was first questioned by them in early 2013, Lagarde has defended her role by suggesting her then-chief of staff, Stéphane Richard, now Orange CEO, was responsible for the principal decisions made regarding the arbitration process, while she has also claimed she was not kept fully informed.

'It was not easy reading'

On July 11th 2008, the day that Tapie was awarded the 404 million euros, finance minister Lagarde issued the following statement: “This arbitration, delivered by incontestable figures, was engaged upon by the parties [involved] to put a definitive end to the litigation proceedings that have been ongoing for almost 15 years. The greater part of the compensation decided by the verdict will return to the public purse, through the debt obligation held by the CDR and the payment of taxes and social contributions which were due to the State.”

During initial questioning by CJR magistrates on May 23rd and 24th 2013, she was asked about her description of the members of the panel of arbitrators as “incontestable”, (one of them, magistrate Pierre Estoup, was later placed under investigation for “organised fraud”), why her statement minimised the amount that Tapie would receive – which in reality was, after deductions, 280 million euros – and why did she suggest no appeal against the decision was being considered. “The statement had not been submitted to me before its publication,” she replied.

Enlargement : Illustration 2

One key part of the case against Lagarde will revolve around how, as a minister, she responded to the views expressed on the arbitration by the Agence des participations de l’État (APE), the body whose job it is to ensure the state gets maximum value from its stakes in any businesses.

On July 23rd, 2008, just more than two weeks after the arbitration award, this organisation wrote to Lagarde about whether the Consortium de réalisation (CDR) – the state body that took over Crédit Lyonnais's liabilities after it collapsed – should appeal against the arbitration outcome. The APE pointed out that while one expert lawyer consulted on the verdict had said an appeal had little hope, another, Benoît Soltner, had said the opposite and in forthright terms. In conclusion, said the APE, the CDR could be considered to have “serious” grounds for fighting the award.

In May 2013 the CJR judges therefore pressed Christine Lagarde on why she had not sided with the APE's view. She replied: “I had been given multiple and varied opinions. [The lawyer] Soltner, in the second of the opinions that he provided, expressed a view more favourable to the annulling [of the award] but his written [opinion] was not easy reading. In those circumstances the second opinion was not enough for me to go back on my initial position which did not lean towards an annulment.”

On July 28th, 2008, a few days after the APE letter was sent, the ministry of finance had issued another press release. It said that having taken legal advice “which considered that the chances of an appeal's success was poor” and noting that the parties involved had agreed to “renounce” their right to appeal in the process, Christine Lagarde was formally asking the state bodies concerned to back the decision not to seek an appeal. This statement dominated the news that evening. The release, however, was a lie. For as Mediapart has made clear, while two lawyers consulted by the state had been in favour of no appeal, two others, including Benoît Soltner, had been in favour.

The CJR judges, therefore, asked Lagarde how such a press release could have been issued in her name. She replied: “I did not have personal knowledge of the content of this press release before it was made public.”

An even more astonishing episode involves the emergence, some weeks after that press release, of the first doubts about the declarations of independence involving one of the arbitration judges Pierre Estoup. This is a crucial matter because it shows that as early as the autumn of 2008 the then minister of finance was aware of problems that could have led to the arbitration award being appealed against and eventually annulled; potentially saving the taxpayers 404 million euros.

'It would have been preferable if I'd taken more of an interest'

On the 3rd and 13th, November 2008, the CDR held meetings to decide its course of action. However, according to Lagarde's testimony this issue was not a pressing one. “During the almost daily meetings with the head of my ministerial office, he quickly talked about a problem relating to the third arbitration judge, Monsieur Estoup,” she told the judges. “He indicated to me that the necessary consultations had been made and that the problem had been sorted. At that time I did not pay particular attention to this problem. Today I obviously realise that it would have been preferable if I had taken more of an interest in it.”

Lagarde's difficulties over her handling of the advice from the APE do not stop there. During her appearance before the CJR in 2013 she told the judges on numerous occasions that she had not been aware of notes that the APE had sent to her regarding the arbitration affair.

These memos first of all warned about agreeing to an arbitration process and the risk of illegality in the process, then after the award had been made they drew her attention to the possibility of an appeal. “I want to make clear, following your question, that I have discovered, after the event, a certain number of memos from the APE which had not been brought to my attention, or that I did not have at that time,” she said.

However, the judges persisted and observed that the head of APE at the time Bruno Bézard – today the director general of public finances – had written a note on January 9th, 2007, setting out that body's point of view. It made clear that in the ongoing judicial saga between Tapie and the state-owned CDR, the state was in a strong legal position after a judgement by the court of appeal the Cour de Cassation. Lagarde told them: “I was not aware, at the time I took office, of the memo of January 9th, 2007 from APE.”

The judges then referred to another letter from Bézard, this one dated August 1st, 2007, in which he formally told the minister: “I can thus only advise the minister against the arbitration route, which is justified neither from the state's nor the CDR's point of view.” Why had the minister not paid attention to the head of a state body that knew the case better? “As I indicated previously, I had no knowledge of this memo at the time it was drawn up. I cannot therefore reply to that question,” Lagarde told the judges.

Enlargement : Illustration 3

It would seem from her replies to the judges, therefore, that Lagarde did not read any of the memos setting out the APE's formal position, even though this was a controversial case. Yet, though the judges did not press her on this, this position poses a problem for the head of the IMF. For it contradicts what she had told members of the National Assembly's finance committee on September 23rd 2008 during their own investigation into the Tapie affair. Having informed MPs that the APE was “regularly consulted” on such issues, she added: “It sent me memos right throughout the case. In general they involved relevant analysis that was often conservative in its view of how well-founded was such or such a step; in particular it engaged in an analysis of the legal consultations that had been provided.” Lagarde told the MPs: “I took notice of their recommendations with interest and I compared them with the other opinions that were sent to me.”

So while Lagarde told the judges she had no knowledge of the memos from APE, or at least not until afterwards, the IMF boss told MPs nearly five years ago that she had “taken notice of them with interest”. Clearly Lagarde was lying on one of these occasions; but whether to the MPs or to the judges one does not know.

The former minister’s capacity to mislead is also shown later during her questioning when the judges referred to a letter that Christine Lagarde wrote on October 23rd 2007 to the head of the public body, the Établissement public de financement et de restructuration (EPFR), which oversees the CDR. This is an important letter for up to this point the CDR had hoped that, based on an old contractual clause, it would get Crédit lyonnais to agree in writing to compensate it to the tune of 12 million euros. Crédit lyonnais's refusal to do so had blocked the use of arbitration. In Lagarde's letter she stipulated that obtaining this guarantee was no longer a prior condition to going to arbitration. It was this letter, therefore, that gave the arbitration process the green light.

'The way it was presented to me did not attract my attention'

However, Christine Lagarde told the judges that she was not responsible for this letter, suggesting that her then chief of staff Stéphane Richard – now boss of telecommunications giant Orange and himself under investigation for conspiracy to defraud in relation to the Tapie case – had perhaps used her ministerial 'signature stamp' to send it. “The letter that you have just reminded me of poses me a real problem,” Lagarde told the judges. “I don't think that I would have signed a letter of this nature if I had been in a position to read it over. I would add that it is clearly not a letter drafted by APE and that it was probably written during my absence from Paris in as much as its date corresponds to the time of the general assembly of the IMF in which I took part in my capacity as minister.”

Lagarde continued: “In this respect I undertake to find and send to you a document that confirms what I'm saying. In addition I note that this letter of October 23rd, 2007, bears a signature that has used the 'signature stamp'. At your request I make clear that the signature stamp could only be used with the prior agreement of the chief-of-staff [of the ministerial office] or their deputy, on the one hand, and of the director of the office on the other.”

When this revelation was later leaked, it was suggested in several newspapers that Lagarde had been deceived by chief-of-staff Stéphane Richard and the head of the CDR at the time, Jean-François Rocchi. However, this interpretation is open to question, for it is not hard to establish that the ex-minister's comments are not reliable.

For it turns out that on Tuesday October 23rd, 2007, Christine Lagarde was not in Washington for the IMF general assembly but was instead in Paris. It is not hard to establish her movements through media reports of that day. In the morning she gave an interview to France Inter radio about consumer spending power, then later presided over a conference on employment at the ministry of finance. A press release also indicates that at midday the minister had taken part in a press conference with two other ministers.

So it is clear that Lagarde misled the judges over the date. But on the substance of the issue Lagarde's reply was equally astonishing. For a look back at what the then minister told MPs in September 2008 reveals that not only does Lagarde talk about that 2007 letter – she claims ownership of it. “I willingly confirm having given instructions [to the managers at EPFR] that they support the decision of the CDR to go to arbitration. I have never hidden that, I take responsibility for the written instructions that I gave on that occasion...”

Once again it appears that Christine Lagarde lied about this; either to the judges in 2013 or to MPs in 2008.

In fact, when one studies Lagarde's replies to the court closely, it becomes clear that she was not blinded by the machinations going on around her or so inconsistent as to not read the memos provided by the APE. It is very apparent that she supported the arbitration, including the most controversial parts of it, in particular those parts that awarded Bernard Tapie damages for moral prejudice.

In the instructions that Lagarde gave as finance minister on October 10th, 2007, to senior civil servants at the EPFR – the Établissement Public de Financement et de Restructuration (EPFR) the body that controlled the CDR – she wrote that the arbitration would be conducted “on a legal basis”, that the judicial decisions made would be respected, and that those decisions were under the aegis of “three incontestable figures” Pierre Mazeaud, Jean-Denis Bredin and Pierre Estoup.

The minister went on to say that the arbitration would deal with all litigation between the parties. The arbitration, she wrote, would also be accompanied by a reduction in the compensation for the opposing party, which would have a ceiling set at 295 million euros for the liquidators of the companies belonging to the former Tapie group, and at 50 million euros for the “liquidators for the Tapie spouses”.

In other words, Lagarde herself had accepted these exorbitant compensation levels and even a huge level of damages for moral prejudice – 50 million euros – even if she had not used that form of words herself. Later, she claimed that she had not been aware that the 50 million euros referred to damages for moral prejudice, and blamed it on others. “The way in which the costings were presented to me did not catch my attention, though my attention would have been drawn had those same 50 million euros been presented as corresponding to moral prejudice.”

In essence Christine Lagarde signed a letter which entailed a major commitment of public funds and later claimed to the judges that she had not at the time understood the impact of what she had signed.

One other curiosity of the case emerged following the search of a computer used by Bernard Tapie's lawyer, Maurice Lantourne. On it was a memo entitled “Lagarde” and dated September 20th, 2008. This was three days before the then-finance minister appeared before the National Assembly's finance committee to be questioned about the affair.

When she was questioned by the judges on the CJR it was pointed out that there were odd similarities between the lawyer's note and what Lagarde told French MPs three days later. “This document and its contents could lead one to believe that the opposing side's lawyer had taken part in preparing your line of argument at the National Assembly,” said the judges. Lagarde denied any knowledge of the note. “I was astonished when I discovered the existence of this document in the file. You're asking me if I can rule out that this could have been prepared and intended for one of my colleagues. I have no idea but that seems totally inconceivable to me,” she said.

Even before Christine Lagarde announced her candidature for the post of managing director of the IMF, it was clear that there were strong reasons to suspect she would face legal proceedings in the Tapie case. On the day she announced her bid to head the IMF, on May 25th 2011, Mediapart questioned her over the affair at a press conference in Paris (see below with English subtitles).

-------------------------

- The French version of this article can be found here.

English version by Michael Streeter and Graham Tearse