It was an episode in French industrial history that took place more than six decades ago. But the bitter memories of the 1948 coal miners' strike in the industrial north of France still remain for those few strikers still alive and their families who continue to battle for justice. Now journalist Dominique Simonnot of French investigative weekly Le Canard enchaîné has written a book about this major two-month industrial dispute, which was crushed by a socialist government with the help of 80,000 troops and which led to six deaths, jail for many strikers and the sacking of 2,950 miners.

Her book plunges into the archives both of that period and the modern day, drawing on documents which detail the ongoing struggle of families to get full justice for those miners who were, in many people's views, unjustly convicted of crimes at the end of the dispute. But perhaps the key contribution of Plus noir dans la nuit ('Blacker by night') lies in the accounts of the men and women who took part in the dispute, and whose lives, and those of their children and even grandchildren, have been blighted by it ever since.

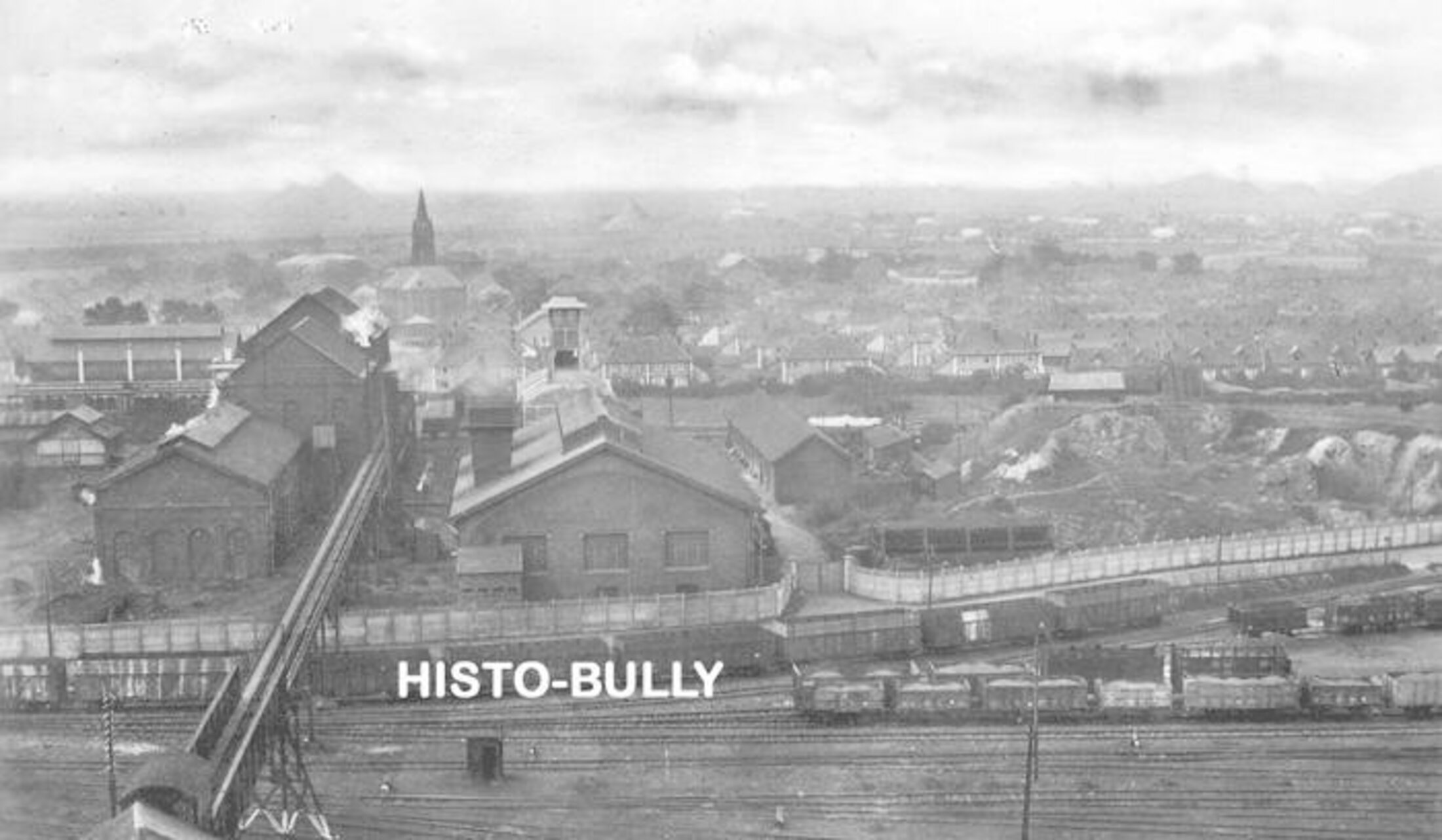

One of those colliery workers is Norbert Gilmez, 92, who took part in the strike, was later convicted and who is still battling for justice. Indeed Norbert, a life-long communist from Bully-les-Mines in northern France, seems to have provided inspiration for Dominique Simonnot's book. “When I got into the train for Paris, Norbert stayed on the platform, until it left. And that evening, watching his thin silhouette disappear, I resolved to go over everything that he had just finished telling me,” writes the author.

For the inexhaustible Norbert – who might write someone a letter of 'only' 28 pages because he's not feeling at his best – the strike that began in October 1948 was the miners' “epic saga”. But he also reveals the personal cost to him, his family and others. After the end of the dispute his wife Lucienne led a reclusive life and, three generations later, family members bearing his name still encounter problems when looking for a job or pursuing their studies. He says: “We've had a little life, an ugly life.” In material terms, that is certainly true.

And yet the strike itself had started with high hopes. The action had the backing of 84% of around 259,000 miners across a swathe of northern France from Alès to Firminy, and from Merlebach to Béthune, as the colliery workers tried to protect their hard-won rights and wages that were threatened by a fall in production. But what is remembered most today is the level of repression used against the miners who took part, led by the socialist interior minister of the time Jules Moch. His name is always pronounced 'moche' by strike veterans, evoking the French word for 'ugly' - in this context, 'ghastly'. He mobilised around 80,000 riot police and reservist troops, equipped with tanks and cannons, to subdue hard core strikers, resulting in six deaths, while nearly 3,000 mineworkers were jailed or sacked for having gone on strike.

Miners wrote on the colliery walls venting their anger at the action of the Compagnies Républicaines de Sécurité (CRS), the formal name for the riot police who played a prominent role in the suppression of the strike. Two decades later in the social protests of 1968, the student revolutionaries may have thought that they were the originators of the slogan 'CRS = SS'. But in fact it was the colliery workers in 1948 who first coined it. In 1948 the SS were still fresh in the memory and many of the miners had personal experience of them. For in 1941 around 100,000 miners in northern France had carried out an heroic but high-risk strike in a bid to deprive the occupying Germans of much-needed coal. This strike, one of the first high-profile acts of resistance to the Nazis in France after the Occupation began, was brutally suppressed, with a number of executions and 270 people being deported.

Interior minister Jules Moch had himself played an active role in the Resistance during the Second World War. But this did not stop him – and others – branding the strikers in 1948 as members or supporters of the communist international movement Comintern. During one strident four-hour speech in the National Assembly Moch claimed the existence of a secret note from Soviet official and Comintern organiser Andrei Zdanov, urging the workers to go on strike and even spark revolution, though the note may well never have existed. He also spoke of Romanian fascists being transported in and of gold being shipped in from Bulgaria. These, of course, were uncertain times, the start of the Cold War and of the Marshall Plan aimed at putting Europe's shattered economies back on their feet.

Enlargement : Illustration 2

So it was that the coal-face workers, the heroes of 1945 and the heroes of 1946, too, when they exceeded production targets, had by 1948 become enemies of the “republican regime” when they embarked on an autumn strike. There were several reasons for the industrial action. The rights that miners had worked so hard to acquire, in particular over industrial illnesses and conditions such as silicosis, and accidents at work (which killed a number of miners every year), were being eroded. Production had also reduced, and wages with it. Though industry minister Robert Lacoste apparently considered miners' living conditions to be perfectly acceptable, poverty was never far away in the miners' cottages at a time when inflation was causing the price of bread to rise by 200%. A reporter on L'Aurore, a newspaper not known for its left-wing trade union sympathies, wrote at the time: “The number one ally of Comintern is butter at 950 francs a kilo.”

All such details appear in Dominique Simonnot's book, for which she combed through reports, newspaper cuttings, archives and letters. But she also went much further in her research, and this is one of the most interesting aspects of Plus noir dan la nuit. She went with Norbert Gilmez around the Brebis housing estate – what remains of it – in Bully-les-Mines, learning the history of the houses, the evictions and also the story of friends, many of whom have since disappeared. All the time she asked lots of questions, including difficult ones.

The 'red queen'

But above all the author met the women involved, Simone, Jeanne, Colette and others. Often widowed today, at the time they were deeply involved in the struggle. In the 1941 strike the miners' wives had dared to demonstrate, and the local German Commandant had in the end banned them from leaving their homes; but they forced the soldiers to retreat. One has only to look at the short documentary film that Louis Daquin made about the 1948 strike, La Grande Lutte Des Mineurs, to see that the women were also present in the post-war dispute. It is worth noting in passing that interior minister Jules Moch, fearing the impact of the film if it were broadcast, had the negatives seized.

The women remember the mood on the Brebis estate and the fallout after the end of the strike, as well as the feeling of solidarity. They recall the family rows, the difficult task of feeding and clothing children, and were all too aware of the invasive black dust that had to be removed every day. Though 1948 is not so long ago – these are not the days of Émile Zola and his novels depicting the grimness of life in the nineteenth century - on occasions people were forced to go out in the snow in their slippers because they had no shoes; and jumpers were unpicked ten times or more to reknit them.

The miners and their families knew what they were risking by striking, jeopardising their lives on the Brebis housing estate which at the time was seen as a desirable place to live, a triumph of the paternalism of the era. On the estate they had a house (though it was often small, shared and came after a long wait – all very different from the the mining engineers' homes), they had free heating – from coal, of course – a nursery, medical visits, a maternity hospital, a garden to grow vegetables and a communal hall. It was the time of free and republican schooling. There was a street market and an active social life. Of course, there were people who kept an eye on you, who would inform on you if your garden was left untended or you didn't make it to church mass. And there was also a weekly and obligatory cleaning of the streets.

Enlargement : Illustration 3

The toughest times for the miners were not the moments during the strike when they felt ready to sacrifice their life for the cause, but the long years that stretched out afterwards, the “ugly life” as Norbert Gilmez put it. But one must also remember the extraordinary solidarity that greeted them at the time. This was largely based around the CGT trade union, but it was not only activists who got involved; miners' children were taken in, fed and kept warm by thousands of families, including most famously the Belgian Queen Mother Élisabeth, who was to earn the nickname of 'red queen' for her sympathy towards socialist regimes.

Nor should one forget people such as Dr Charles Coucke and his wife Paulette. He was the colliery doctor, fighting to get silicosis recognised as a killer disease, a condition which most salaried doctors played down, regarding as healthy even those men who were laid low by it. She helped organise handouts of clothes and shows, even getting mining engineers to contribute, and put up a Christmas tree when all around was grim and sombre.

Things got tougher later. Though it is interior minister Jules Moch who is remembered for his hard-line stance against the miners, his colleague André Marie, the justice minister, was almost as implacable. Although many miners had been arrested during the dispute, the charges against them soon looked flimsy. A number were accused of firing at the army, yet 22 journalists and photographers gave written evidence to the contrary. And blows had certainly been exchanged, but in particular with members of other unions. There was also a claim that a group of CRS officers had been herded off into a mine shaft for a night. This was true, but they were all allowed out the following morning in one piece. Meanwhile at Alès a cannon shot smashed into the young miners' sporting association building. All in all, the judges might have been tempted to pass suspended prison sentences on the strikers.

'Collaborators did well while the workers suffered'

But in the end it was a story of summary justice, lawyers being prevented from doing their job, mass arrests and a succession of short jail terms for “obstructing the freedom to work” and “obstructing the proper functioning of the national collieries at Bully-les-Mines”. An extraordinary atmosphere reigned among the judges, who were ordered by ministerial circulars to be tough. One reluctant prosecutor was suspended from duty, and some judges were denounced for the “deplorable weakness” in their sentencing. At the National Assembly, meanwhile, the journalist, Resistance fighter and politician Emmanuel d'Astier de La Vigerie contrasted what he saw as the indulgence of the state towards those who had engaged in lucrative economic collaboration with the German occupiers in the war with the “scandalous repression against the working class”.

Another Resistance hero and left-wing MP Maurice Kriegel-Valrimont also attacked what he saw as double standards. “The well-known outcome is that the traitors come out of it well and that the workers are mercilessly hammered,” he said. And the communist newspaper L'Humanité stated: “While he closes the files on the collaborators, Monsieur Marie broadcasts the names of judges who do not punish worker activists enough.” André Marie, who had himself been active in the Resistance and endured 20 months in Buchenwald concentration camp, was forced to resign in February 1949 over accusations the government had been overly lenient towards an economic collaborator. But the convictions, prison sentences – between 15 days to three months on average – and the sackings continued.

The collieries occupied a central role in this region of France and the powers-that-be had long memories. A short story, briefly recounted in Simonnot's book, sums up the harassment meted out by the authorities. In 1942 a 36-year-old communist Resistance activist Émilienne Mopty from the nearby mining town of Harnes – who as a miner's wife herself had been a key figure in the women's protests during the 1941 strike - was arrested by the Gestapo and tortured, transferred to Cologne and beheaded. In 1948 her remains were identified and her body was repatriated to be buried with dignity. But two key people were absent from the ceremony – her sons. Both communists like their mother, they were in prison for having been involved in the strike action, and they were not allowed to be present at their mother's funeral ceremony.

The suffering of the former strikers continued for years. Some miners who had earlier achieved the status of non-commissioned officers in the army after volunteering their services for their country saw themselves stripped of their rank when they were sacked from the collieries, something they never dared to tell their children. Other miners had to wait 17 years to get mains water connected, were evicted from their homes altogether or found themselves forced to live in an unhealthy blockhouse which was designated as their tied accommodation. As for employment, they were barred everywhere, picking up a half-day or one day's work at most, unable to work for firms that were still dependent on the collieries. Their priority was to find a place to stay and keep it. No one was interested in them any more.

Twenty years later and it was the turn of the miners' children to get knocked back in their careers, including in the gendarmerie, because of “father's past”. Yet despite the many difficulties some families kept going through it all and prefer to remember the house full of friends, the solidarity shown by others, or an incredible 15-day dream holiday in Albania laid on by the French Communist Party.

In 1981, and with the arrival of a socialist government under François Mitterrand, there was renewed hope for former strikers who were still alive. An amnesty law passed by the new government formally decreed that the miners' dismissals had been carried out following strike action, an official recognition of the facts that paved the way for legal action. The wrongful sackings, the ruined lives and the convictions were finally being recognised and were to be compensated. Former miners such as Georges Carbonnier and Norbert Gilmez pulled together all the information they had. Then the judicial marathon began and so did the many letters that had to be written, as the various socialist ministries appeared to play a giant hand of Old Maid, the card game in which the player left holding the 'odd' card at the end loses. The labour, justice, industry ministries...each one “examined the case with the greatest attention”, and then referred it on to the next ministry.

But the number of ministries is not unlimited, and so the case went round and round in circles. Nearly quarter of a century later – enough time for many of the former strikers to have disappeared – and it was, ironically, the right-wing Nicolas Sarkozy, then minister of finance, who found in the strikers' favour when in 2004 he awarded the former miners or their families €14,550 in compensation over lost heating allowances and accommodation from that era.

The legal battle was almost as arduous, despite the work carried out by militant lawyer Tiennot Grumbach until his death in 2013. It was not until 2011 that the French court of appeal finally recognised the wrongful nature of the sackings and awarded €30,000 damages to the miners or their families. But the then finance minister Christine Lagarde – in office under President Sarkozy – successfully appealed against this ruling in 2012 and the strikers were unable to get their hands on the money. It was not until the following year, 2013, that the new finance minister Pierre Moscovici - under President François Hollande - agreed that notwithstanding the court's ruling the men and their families could keep the compensation. This was, he said “in order to take into account the particularly strong human dimension of this case”. However, the miners' cause is still not fully won. They had hoped for an amendment in a proposed law in 2013 that would have given them a “social amnesty” for the events of 1948. But in April 2013 that planned legislation was shelved.

March 2014 saw a political postscript to the story. In France's local elections the far-right Front National performed strongly, winning control of the town hall at Hénin-Beaumont in northern France, another of the places where the 1948 miners' strike took place. But a few kilometres away, in Bully-les-Mines and neighbouring Mazingarbe, the electorate voted overwhelmingly for the Left.

---------------------------

Plus noir dans la nuit ('Blacker by night')

by Dominique Simonnot

267 pages, published by Calmann-Lévy, €17.50

The French version of this story can be found here.

English version by Michael Streeter