After months of contact via intermediaries, the meeting with Amedy Coulibaly finally took place on December 31st 2008. Wary of journalists and because of the risks he ran, he had until then been reticent about accepting an interview.

Coulibaly arrived at the emptied offices of an association situated at the centre of the Grande Borne neighbourhood in Grigny, a run-down Paris suburb characterized by high-rise housing estates situated about 20 kilometres south of the capital.

Coulibaly, then aged 26, born in France and whose family came from the West-African former French colony of Mali, was a tall and physically imposing figure. He was polite, amiable and spoke in a composed and clear manner. Nothing gave a clue that he would in a few years become one of the killers of the January 2015 terrorist attacks in Paris.

Coulibaly shot and killed a policewoman and seriously wounded a street maintenance worker in the Paris suburb of Montrouge on January 8th 2015, the day after the massacre of 12 people in and around the offices of Charlie Hebdo magazine perpetrated by brothers Chérif and Saïd Kouachi. Coulibaly would claim that he was acting in coordination with the Kouachi pair, who were longstanding acquaintances.

The following day, January 9th, when the authorities issued a 'wanted' notice for his arrest, Coulibaly, heavily armed and claiming to act in the name of the Islamic State group, attacked a kosher supermarket on the south-east edge of Paris, at the Porte de Vincennes, where he took staff and customers hostage before shooting dead four of them. At the end of a four-hour siege, Coulibaly was himself shot dead when police commandos stormed the store.

Back on that day of December 31st 2008, Coulibaly, arms folded and with a fixed stare, had decided to answer all the questions about his time in prison, speaking about what had most affected him and about his future. “Jail transformed me,” he said. He was known by the nickname ‘Doly’, and also ‘Hugo’, which he used to remain anonymous. He didn’t reveal his identity because he had, with four fellow prisoners, illegally filmed life in block D3 of the Fleury-Mérogis prison.

Some of the images Coulibaly recorded were included in a video recorded before his attack on the Hyper Cacher kosher store, and which was posted on the internet two days after the attack. In it, Coulibaly claimed allegiance to the Islamic State group and announced: “You attack the caliphate, we attack you.”

Situated about 30 kilometres south of Paris, Fleury-Mérogis is the largest prison in Europe. According to figures published by the French-based International Observatory of Prisons, Fleury-Mérogis in 2008 housed 3,900 prisoners, well over its capacity of 2,400. The prison is divided into five blocks, where prisoners are grouped according to the region they reside in.

Asked why he was given a jail sentence, Coulibaly replied: “I had a quasi-normal school record, with a [secondary school professional qualification] BEP diploma [...] I was caught at 17, in September, just before the new school year for the baccalauriat. I was sentenced to three months as an example after the theft of a motorbike. It was a set-up.”

“The trigger was the first incarceration, but I would have been [sent] there in any case,” he said.

He was given a second jail term for what he said was “a fight”. He then decided, he said, that if he was going to be sent to prison “it might as well be for something”. He went on to commit armed robbery, targeting banks and discotheques, while minimizing the violence involved and the fear his victims might have felt; “There’s worse,” he said. “I spent 18 months in prison. After two-and-a-half months on conditional bail I went back.”

He described his first stay in prison: “I was terrorized,” said Coulibaly, who said he felt “hate against the justice system, the police, the prison administration.” In a reference to black people and Arabs, he said “they’re harder with foreigners”. After what he said was another armed robbery he committed, and dealing in cannabis, he spent the period between the ages of 20 and 23 in jail. “That was when we filmed,” he said.

He and his jailmates recorded their daily lives in Fleury-Mérogis, capturing the poor conditions of the cells and the showers, the bare toilets placed in the cells, and the communications with other prisoners - called 'yoyos’ - by a system of pieces of ripped sheets hung out of the windows. Coulibaly said he shared a cell with an old acquaintance who went, variously, by the names of “Karim” and “Ficelle”. It was with him that Coulibaly shared the filming project, which he said was to prompt public debate about the dehumanizing conditions prisoners lived in. “You always see the same faces,” he said. “Prison - you’d think it was the neighbourhood.”

'You either kill time, or time kills you'

The two men passed on the images they shot to acquaintances in their home neighbourhood in Grigny. Hours of rushes ended up with an independent production company, iScreen. I was involved with the company in producing a lengthy report based on the images which was broadcast by public TV channel France 2 on its current affairs programme Envoyé special.

After that, we produced a documentary about conditions in French prisons, interviewing former prisoners, their families, sociologists, a former justice minister, Members of Parliament, Senators, officials from the prison administration, prison guards and their union officials, and the governor of Fleury-Mérogis prison.

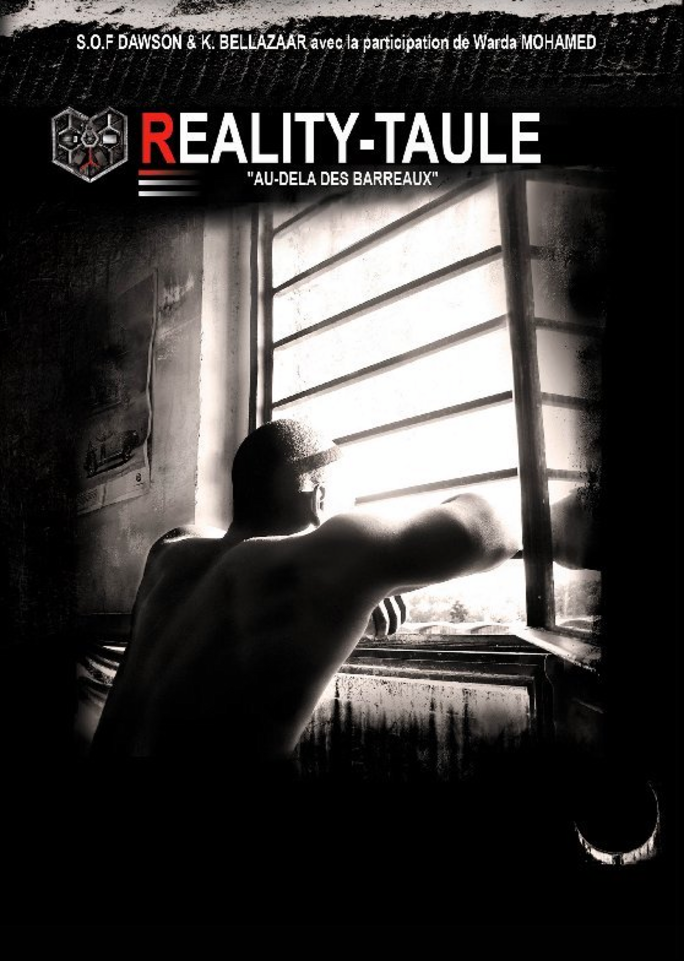

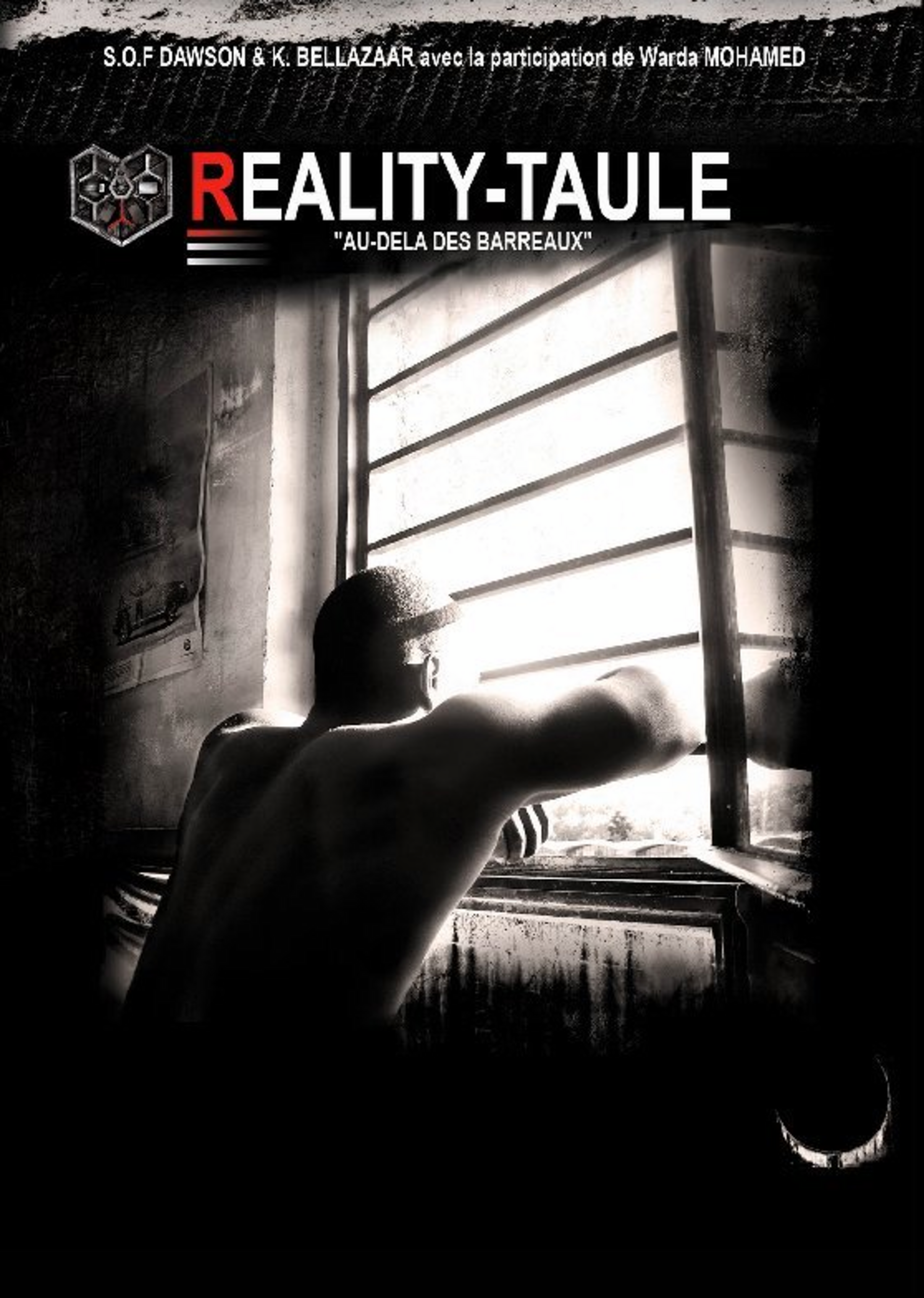

The documetary, called D3, reality taule (Block D3, Reality in the Clink), was screened in partnership with local associations and town halls, and for the first time in Fresnes. A book followed the documentary, made up of texts written by the prisoners and edited by the production company. On the cover of the book (which can be read online, in French, here), entitled Reality-Taule, au-delà des barreaux, (Reality in the Clink, Beyond the Bars), a photo shows Coulibaly, his back turned and looking out through the bars of his cell.

Enlargement : Illustration 2

In the first chapter, ‘Karim’, who, unlike Coulibaly, was in Fleury-Mérogis for the first time, recounts: “When you live in a neighbourhood that’s just beside the biggest prison in Europe, you don’t need to be the cleverest of tipsters to know that you have a real chance of one day going to ‘Club Med’ […] For the shape of the prison, they chose a hexagon. Does that remind you of a country? When you’ve had a stay in the place, you have the nationality for life, without having to request it.”

Fleury-Mérogis is an architectural monster that dates from 1968, and which the contemporary French architect Augustin Rosenstiehl has said did not appear to have been designed to house human beings. After our TV report was broadcast on Envoyé spécial, the prison administration contacted us and gave us permission to film inside the prison. Embarrassed by the images featured in our report, the authorities wanted to show the brand-new building that was to replace Block D3. The building was entirely renovated, with cells resembling sanitised hospital rooms and light-coloured paintwork everywhere, a world so very distant from the images of Coulibaly and his fellow prisoners.

After spending an afternoon in the place as a journalist – and so in conditions completely different to those detained there – it seemed like an eternity. “Either you kill time, either it’s time that kills you,” wrote Coulibaly – under the alias of Hugo - and Karim in their texts.

Karim is the principal narrator in the book, in which it is explained that they got the idea of filming conditions in the prison after seeing a programme on TV. “With Hugo we were zapping around when we came across a report about prisons,” wrote Karim. “It’s crazy what you can be shown on TV and what you are not shown [...] It’s not Guantanamo, but again recently France was singled out by the Council of Europe and organisations like the Red Cross or the Interrnational Observatory of Prisons because of the detention conditions. But when journalists are authorised to come and film, they are shown new or recent cells, and the better renovated showers. You are shown images that are totally different from reality.”

“I suddenly had an idea when remembering a journalist who, during riots in my neighbourhood, approached me to find out whether I could give him images of the inside of a prison, through my contacts with those already there. I said to myself that it would be terrific if we could make our own report [...] Samy Naceri [a French actor who has served jail for assault], a guy like us, was filmed by a guard who sold on the images [...] and that didn’t seem to bother many people. So I don’t see why guys in the neighbourhood couldn’t film the clink and the guards and pass that on to the very same press.”

The financial aspect is discussed, although against the risks involved it does not appear the primary reason for recording the images. “Hugo says that for him, it’s not worth it because in a morning’s hold-up he can make 40,000 euros. Everyone was under pressure because the person who gets caught trying to enter something banned here goes down for at least a year in jail and a fine of 15,000 euros. It wouldn’t even cover our lawyer’s fees. To tell you the truth, I don’t even know what we run the risk of, and even the justice system doesn’t really know because it hasn’t ever been done yet.”

Karim then explained how they developed the project, with Coulibaly choosing the equipment from a TV home-shopping programme. “The presenter demonstrated a small camera that fits in the palm of his hand,” he recalled. To smuggle the camera into the prison, they hatched a plan that the person carrying it should wear a plaster-cast over a supposed injury so that when the security gate scanner alarm rings they could pretend to have surgical metal pins inserted. He recounted how they chose the best candidate for who would meet the person in the visiting room, when he would insert the camera and equipment in his anus, after which others who had permission to attend the visiting room that same day would be needed for him to pass on the equipment.

The book begins: “We dedicate this book to those who would do anything so as never to go to prison and those who would do everything to never return there – Hugo and Karim.” In the preface they describe a caricatural scene: “Everything begins and everything will end here, in a sensitive neighbourhood of the Paris suburbs. It is December 2005. The sirens of police cars wail, tyres screech, the air is full of teargas and dozens of youngsters aged 15-20 confront the police and riot squad who were already on the spot even before the violence began. As usual. […] In general, as of the age of 13-14, it’s unanimous, nobody appreciates the cops. It’s funny because when we were only little, we all wanted to be a police officer. Since then, it has to be believed, something surely happened in order that everything went wrong.”

'I’m optimistic, I’m not unhappy'

During that interview with me on December 31st 2008, Coulibaly spoke of the “death of my friend Ali”, who he claimed was “killed by policemen and I saw the police and justice system lie”. He appeared affected by the event he referred to. “They have no heart,” he said. “They bluff. Since then, I don’t believe in justice because it doesn’t exist.”

In the book they co-wrote, Coulibaly and his fellow prisoners are highly critical of the justice system, underlining what they saw as the relative clemency shown to white-collar defendants, while petit delinquents are sent down. “We are ‘jailbird 4 life’,” Karim writes. “Except that here, there’s no social mix. It’s the France below, the ‘France down under’ as they who live between these walls say. I would like to see more white-collar people here […] If you grab a bag from a granny you go to prison. But if as a banker you get hold of the savings of thousands of old people you can be sure that, at worst, you’ll be given a suspended sentence.”

Enlargement : Illustration 3

A sequence in the report broadcast by Envoyé spécial prompted particular controversy. The crew filmed what, in the words of the commentary, “is what could be called the proceeds of the day for one of the prisoners: banknotes, drugs. Of course, all these things are completely forbidden in prison […] We’re placed here so that we get out of an environment but we find the same, better organised, more concentrated […] and the objects have even more value, even the most simple ones. That makes the traffic even more propitious in prison life.” The book suggests the connivance of prison guards.

Back to the meeting with Coulibaly in December 2008. “I’ve seen everything of the parody of justice,” he said, explaining what for him prison had changed in his life. “It also gave me qualities, like patience and endurance and allowed me to see who liked me, who didn’t like me.” Asked if he had regrets, he answered: “No. In prison, you think of things you would never have thought about outside, because you never stop. It was a period of taking stock of my life. I had what was like an exterior view. Since prison, I know more about human nature. I didn’t know it was so bad.”

He spoke of what had affected him most in jail: “People and freedom. It’s an incredible thing, it has no price. I refused to think outside, it hurts. At the very least, prison serves as a lesson. I believe the judge says to himself ‘at least he isn’t doing anything for three years’. That’s not a solution. Afterwards, there's repeat offending because there’s no reinsertion.”

Coulibaly was the only brother of nine sisters. “They suffered,” he said. I am the only boy and a delinquent never stops. But I’m normal. I’m not evil. There’s worse. Like those who exploit, the politicians with the army, the wars, paedophilia, rotten cops.” Coulibaly, who said during his time in prison he was mixed with “those suspected of terrorism, the Basques, the Muslims and the Corsicans”, categorized violence and crimes.

Asked about his relationship with Islam, he answered: “I learnt about the Muslim religion in prison. Before, it didn’t interest me. Now I pray. If only for that, I’m happy to have gone to prison.”

When Coulibaly left prison he returned to his home neighbourhood in Grigny. In December 2008 he said he wanted to move out. “Others see me as crazy, bitter” he said. “I’m not confident with people, I’m a loner and I don’t need them. In prison, I wanted a single cell so as not to talk with anyone but I was already like that before.” He spoke enthusiastically about his job as a floor operator with Coca-Cola, but remained evasive about his private life. “With conditional bail, I live for the present,” he said. “I get by, and bounce back. I’m optimistic. I’m not unhappy.”

“I want to change my environment and not return to Fleury,” he insisted. “In prison, if people are sentenced for not having a driving licence or for a terrorist attack, they have the same detention conditions. That pushes towards more serious crimes.”

Throughout the interview, Coulibaly was concentrated, and gave precise answers to questions, because, he said, he had the clear aim of recounting his experience to prevent another youngster from “falling”. With a somewhat blasé manner, a touch boasting, he said he considered himself destined to return to prison, as if a fatality. “It’s not like before,” he said. “Youngsters are no longer afraid of prison. But it’s a school in crime. You leave with an agenda full of contacts for armed robbers, with plans, with missions. You are even mixed with terrorists.”

-------------------------

Warda Mohamed writes: Why did I wait one year before publishing this article? When the ‘wanted’ notice was issued concerning Amedy Coulibaly, in which his photo appeared, I thought I recognised him. I did not know his exact identity, for my colleagues had [in 2008] hidden it both to protect him and myself in case of legal action. I was 99% sure but because the accusations against him were so serious I questioned myself, as a journalist and as a citizen, about what I should do. I had interviewed a delinquent, not a terrorist.

Following the terrorist attacks in January 2015, I spent time trying to contact Coulibaly’s family, and former cellmate ‘Karim’ in the hope of meeting them for an interview. I waited in vain until January 13th 2016.

-------------------------

Mediapart English editor’s note: under French law, Amedy Coulibaly cannot be tried posthumously. Compelling evidence suggests he murdered policewoman Clarissa Jean-Philippe, aged 26, in a street shooting attack on January 8th in the Paris suburb of Montrouge on January 8th 2015. A local municipal worker was also seriously wounded in the shooting.

During his attack on a kosher supermarket, the Hyper Cacher at the Porte de Vincennes, on January 9th 2015, Coulibaly shot dead four hostages: they were François-Michel Saada, 63, Philippe Braham, 45, Yoav Hattab, 21, and Yohan Cohe, 20. By the end of the siege, nine people were wounded, including three police officers.

During the siege of the kosher supermarket, Lassana Bathily, 24, a Malian employee of the store, of Muslim faith, hid six hostages in a cold store.

The parallel attack against the offices of Charlie Hebdo magazine, led by the brothers Chérif and Saïd Kouachi, left 12 dead and another 11 wounded. Chérif and Saïd Kouachi were killed in a shoot-out with police, minutes before the police assault on the Hyper Cacher store on January 9th 2015, after they took refuge earlier that day in the offices of a printing company in Dammartin-en-Goële, north of Paris.

-------------------------

- The French version of this article can be found here.