Strangely for a businessman used to making dramatic announcements, Patrick Drahi's latest transaction was a particularly discreet one, in contrast to the fanfare with which his purchase of NextRadioTV, owner of broadcasters BFM and RMC, was announced on July 27th.

Yet it is infinitely more important for the future of his group, Altice, and for its main shareholder, Drahi himself.

An extraordinary Altice shareholders' meeting held on Thursday August 6th in Amsterdam approved a motion to transfer the company's headquarters from Luxembourg to the Netherlands with 91% of the vote in favour. The transaction involved setting up a new company in the Netherlands that bought up Altice SA, a merger that became effective on August 9th. Since August 10th, Drahi's holding company has been quoted on the Amsterdam Stock Exchange.

This may appear to be nothing more than a simple financial transfer, but it is critical for 52-year-old Drahi. Both Luxembourg and the Netherlands are known for welcoming financiers and protecting their interests, but stock market legislation in the Netherlands allows a company to have several types of shares which do not all confer the same rights. This allows dominant shareholders, often families, to retain control over the company and protect themselves from a takeover even if they no longer own the majority of the capital. Fiat Chrysler made a similar move last year, helping the Agnelli family consolidate its control of the company.

The advantages of this set-up did not escape Drahi's notice. The change of fiscal base was accompanied by the creation of two classes of Altice shares, 'A' and 'B' shares, with entitlement to the same dividends but not the same voting rights. While each 'A' share carries a single vote, 'B' shares confer a staggering 25 votes per share. On top of that, the 'B' shares are not quoted, so they can remain in friendly hands.

Enlargement : Illustration 1

The main beneficiary of the change is Drahi himself. He owns 58.5% of Altice Luxembourg through his personal company, Next LP. According to documents published for the transaction, if Drahi were the sole beneficiary of the 'B' shares, he would find himself with 92% of the company's voting rights. And to avoid any criticism later, the merger's auditors warned that certain situations could arise involving conflicts of interest at a later date. Drahi's own interests, as the company's CEO and practically sole decision-maker, might not always converge with those of the company, they said.

So, with a sleight of hand, Drahi has managed to reorganise his holding company in such a way as to keep it under his control regardless of what happens to the actual ownership of the company's capital. With such exorbitant voting rights he has no need to worry about being diluted by outside shareholders and can use the share capital as he sees fit, paying for future acquisitions by issuing new shares. His dizzying spiral of acquisitions can continue, and this is what the transaction was all about.

"Mark Zuckerberg has more than 52% of the voting rights in Facebook with only 18% of the capital," commented a spokesman for Altice. The transaction, he added, "will allow the group [Altice]to pursue its expansion policy without losing control", in a confirmation of his CEO's predatory ambitions.

And these ambitions seem to be vast. In less than 18 months, Drahi has managed to increase his group's turnover from barely 2 billion euros to over 15 billioneuros. And on the personal front, he took 57th place in the world league tables of billionaires in 2015 with a fortune estimated at around 16 billion dollars, or some 14.5 billion euros, according to Forbes magazine, even though just three years ago he could not have laid claim to any rank at all in that league. So why stop now?

"Patrick Drahi is today's Jean-Marie Messier," said an investment banker whose name is withheld, referring to the former CEO of Vivendi whose acquisition spree in the early 2000s almost bankrupted Vivendi. This comparison has often been used in the press, and it is tempting. Except for Drahi's reluctance to expose himself to the glare of media attention compared with Messier’s love of it, the two men have many things in common – like a taste for speed, conquest, an avalanche of transactions, risky financial constructions and creative accounting.

Just as Messier launched into a wave of acquisitions after the 2001 merger between Vivendi and Seagram of Canada, Drahi too seems to place no limits on his plans since he bought SFR, the French mobile phone company – from the post-Messier Vivendi – in autumn 2014, not even a year ago. His group suddenly changed league. From then on there were no holds barred.

Hardly a month goes by without a new announcement. In October last year, before the purchase of SFR was even finalised, he bought Virgin Mobile's French operations. In December he bought Portugal Telecom from the Brazilian telecommunications firm Oi for 7.4 billion euros.

In February this year he snapped up seven magazines from Belgium's Roularta, including magazines l'Express and l'Expansion, for under 10 billion euros. And still in February, he bought out Vivendi’s remaining 20% in SFR for 3.9 billion euros.

In May he took control of French daily Libération, into which he had already injected cash last year. And still in May, he announced the purchase of 70% of American cable operator Suddenlink for 9.1 billion dollars (8.3 billion euros). In July came the purchase of NextRadioTV and formation of a joint venture with its boss, Alain Weill, for 1 billion euros, of which 800 million euros were borne by Altice.

And had he not run up against an implacable refusal from construction group Bouygues, he would have forked out 10 billion euros more to buy Bouygues Telecom in June. In August, Altice shelled out 67 million euros to continue buying up shares in its Numericable-SFR subsidiary, in which it has a near-70% stake.

Over just two years, Drahi's group has ploughed over 40 billion euros into acquisitions, and these have been entirely financed with borrowings. It has not yet finalised its purchase of Suddenlink, yet it is already carrying over 33 billion euros of debt.

'Drahi plays the system very skilfully, very cynically'

The comparison with Jean-Marie Messier, however, has its limits. Unlike earlier business leaders, he doesn’t seek the honours, prestige and power linked to a company quoted on the CAC 40 stock market index. Even if he claims to be influenced by US billionaire John C. Malone, founder of Liberty Media, Drahi is above all a financier of his times.

Enlargement : Illustration 2

Like many of his generation, he understood the significant merits of private equity, building a private fortune in all discretion with the money of others. He knows all the fashionable financial techniques, the jackpots provided by leveraged buyouts.

Like many financiers, he is highly knowledgeable about the workings and circuits of tax havens. His personal company, Next, is based in Guernsey as a trust (a financial status that the OECD has recommended should be scrapped because of its opacity). All his companies were registered in Luxembourg before the holding company at the top was transferred to Amsterdam. His private home is in Zermatt, a Swiss mountain resort popular with the rich and where taxes are almost non-existent.

But beyond his financial skills, Drahi’s success is above all down to the very particular moment following the 2008 financial crisis where the central banks poured stacks of liquidity on the markets, where money is worth nothing. “No Drahi without Draghi” rightly commented French financial daily Les Échos, although in this particular example Drahi is more a creature – a creation even – of Ben Bernanke and Janet Yellen, the successive heads of the Federal Reserve System. His financial operations are first made in dollars and in the US.

“Patrick Drahi plays the system very skilfully and very cynically,” commented a merchant banker whose name is withheld. “He makes the very best out of our period when money is worth nothing anymore. The managers of pension funds, of investment funds, who are looking for returns are ready to subscribe blindfolded to every product that gives them a few returns. That allowed Patrick Drahi to finance his expansion in all haste, with loans of 6% when he should normally have paid 11% to 12%, or even more. Without that, he would never have been able to have the itinerary that he’s had.”

After having worked at Philips and in the Swedish group Kinnevik, Drahi launched a consultancy firm in 1993 called CMA. Among its clients was notably United Pan European Communication (UPC). Already at the time he believed that cable communications were the technology of the future. He helped with the purchase of bits of cable networks in France, the remains of the former cable project launched with much trumpeting by the French state in the early 1980s. As of 2004, his company bought into cable companies around France and in 2005 he took over Numéricable and Noos.

From that moment Drahi was to benefit from powerful financial backers, such as US investment funds Carlyle and Cinven, French private equity firm Pechel Industries and the bank Société Générale. Along with this, he was advised by François Henrot, managing partner of Rothschild & Cie Banque. He was notably a senior advisor to former France Télécom boss Michel Bon who left the group in a state of near bankruptcy in 2002, with 70 billion euros of debt that it is still paying off.

But depite all his backers, Drahi was still just dabbling. While his group was presented as the biggest cable operator in France, its activities remained limited while the sector never truly developed. His principal company, Noos, a former subsidiary of Suez-Lyonnaise des eaux, had such a wretched commercial reputation that he had to get rid of the name and place its activities under the single operating name of Numéricable.

Drahi only really took off in 2009, when the Federal Reserve brought its rate down to zero and when investors were ready to try anything given there was no longer any risk involved. The banks were all the more inclined to take part in the development of Altice given that they acted as simple intermediaries. “If they carry the risk of one operation over 15 days it’s an absolute maximum,” said a source well informed of Drahi’s ascension, speaking on condition of anonymity. “Once they raised debt financing, they hasten to sell it on on the market to investors who only look at the returns.”

SFR cost more than 60 million euros in consultancy fees

From 2009, Altice became an assiduous client of the high yield market (what was formerly known as junk bonds). That allowed him to feed his hunger for further acquisitions. Drahi bought cable operator Hot, followed by Mirs, a small Israeli mobile phone company and which placed him in competition with one of French businessman Xavier Niel’s closest allies. Drahi bought up cable and mobile phone companies in Belgium, South Africa, the Dominican Republic, and in the French Caribbean islands of Martinique and Guadeloupe, as well as in Mayotte, the French Indian Ocean archipelago.

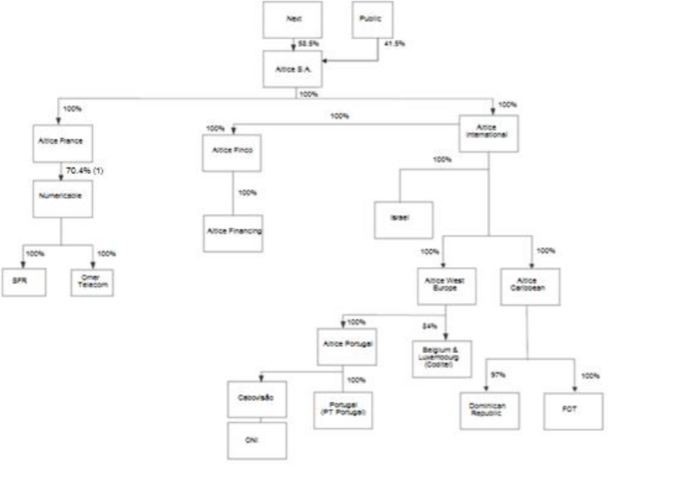

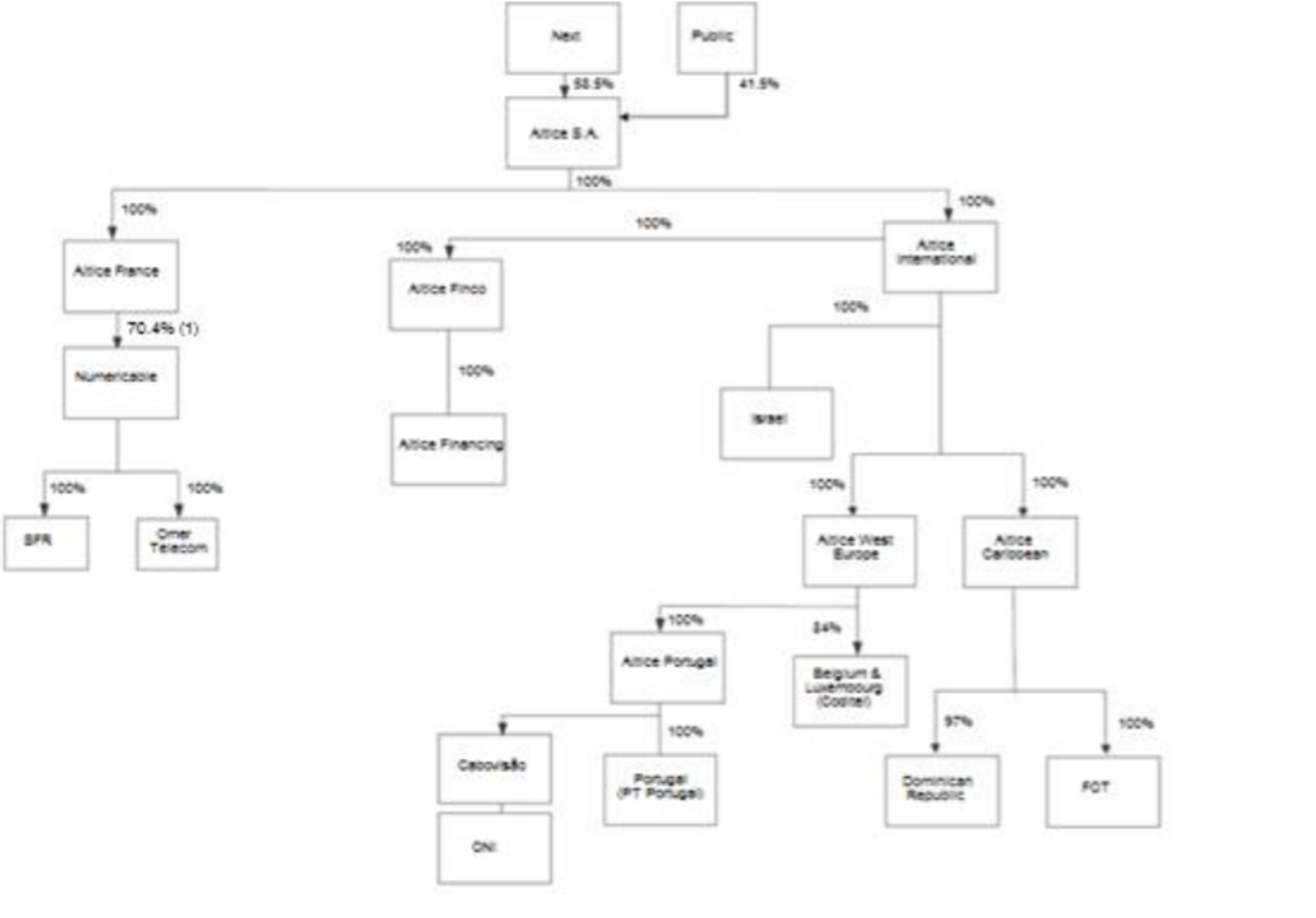

Enlargement : Illustration 3

On each occasion, Altice acts as a holding company. All its operations are carried out in the same manner: an entity is created in Luxembourg and receives a pinch of capital from the principal investment fund that groups together the interests of Altice. This structure has a leverage effect, offering the guarantee of the assets repurchased against the debt taken on. Over the past few years, about 20 companies were in this manner registered in Luxembourg, including Altice Africa, Atlice Carribean, Be Ready.

Meanwhile, a number of companies were created to offer financial incentive for managers. Since Altice became a listed company in 2013, the system has hardly changed. In compensation for the stock option plans that had become invalid, Drahi and his management team, notably including Dexter Goei, Dennis Okhuijsen and Jérémie Bonnin, awarded themselves a stock option plan of 250 million euros over five years, of which 75 million euros was for Drahi alone.

Everyone was happy, from merchant bankers, legal advisors to the banks – all of them picking up commissions along the way. According to documents made public by Numéricable, the acquisition of SFR cost more than 60 million euros in consultancy fees. The transfer of Altice SA from Luxembourg to Amsterdam generated more than 11 million euros in commission payments, most of which went to auditing and legal consultancy firms KPMG and Deloitte (which are apparently key players in Luxembourg, as illustrated by the revelations of LuxLeaks).

However, the purchase of SFR has changed the situation. While the acquisition of France’s second-largest mobile phone operator gave a new dimension and means for Altice, it has also upset its organisation. The 17 billion-euro cost of the transaction was too high for Numéricable alone to handle, with equity of 265 million euros and debts of 2.8 billion euros, and even the most adventurous bankers would not have supported it. Parent firm Altice therefore had to pass over use of investment funds and fully engage itself alongside its subsidiary in the operation. On top of subscribing to the 4 billion-euro capital increase launched by Numéricable, Altice took on debt of 7 billion euros for the purchase of SFR for which it had to offer almost all its shareholdings as a guarantee.

Without intending to, Patrick Draho finds himself in the same uncomfortable situation as Jean-Marie Messier with Vivendi in 2002: with a heavily indebted holding company that has no other revenue than than the dividends of its shares. What is more, these are particularly weak because all the resources of the different companies are mobilised to refund acquisition debts.

Until now, credit rating agency Moody’s appears to be the only one that is concerned by the group’s frenetic acquisitions and accumulation of debts. In May, following the announcement of its purchase of 70% of Suddenlink Communications, Moody’s announced it was placing Altice under ‘review for downgrade’ while the group’s debt was placed in B3 category, the equivalent of junk bonds.

While the climate on the financial markets tightens, the support Drahi has received over the past years from financial circles could be withdrawn just as swiftly as it was gained. An initial and indirect warning came earlier this month, when US media groups, including Viacom and Times Warner, which had also juggled with their capital and debts these last few years were heavily penalized after their poor financial results. Their debts were given a rough ride on the markets, underlining that the times when investors closed their eyes to it was coming to an end.

“Patrick Drahi is smart,” commented one analyst, whose name is withheld. “He knew how to benefit from every opening that was presented to him. He understands well what is happening now.” After the reorganisation of Altice’s share structure earlier this month, a number of financial analysts and observers foresee an obvious next stage: Altice will take over control of its subsidiary Numéricable, paying for the missing 20% of capital with its shares before delisting it. That would allow Altice to have total control of a subsidiary which represents more than two-thirds of the group’s turnover and results. Thus the holding would be able to place its assets and income against its debt.

But will the markets give Drahi the time do so and to be able to put SFR-Numéricable on its feet? The magnate now finds himself in a race against time to succeed in stabilising his group before the climate definitively changes.

-------------------------

- The French version of this article can be found here.

English version by Graham Tearse and Sue Landau