The three-day trial in Bordeaux of Eric Woerth and Patrice de Maistre on charges of influence peddling is the second court case to be heard in the vast, so-called ‘Bettencourt Affair’, a story of corruption, fraud and money-laundering involving the entourage of Liliane Bettencourt, the 92-year-old billionaire and heiress of the French cosmetics giant L’Oréal, first revealed by Mediapart in 2010.

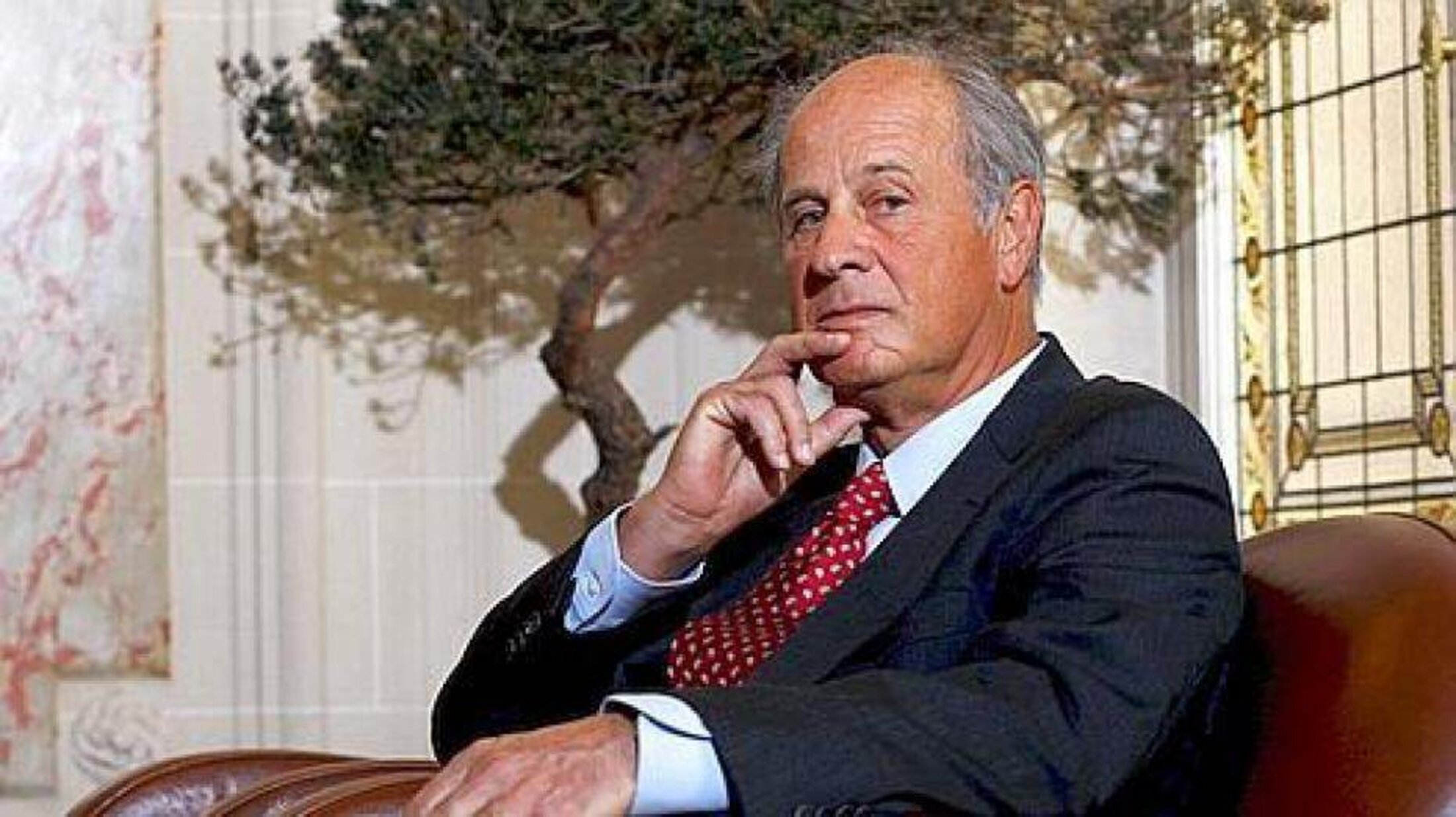

Woerth, 59, and Maistre, 66, were already among the defendants in a five-week trial that ended in February of ten people, including lawyers, solicitors, high-society dandies and nurses, accused of financial profiteering from the mentally frail Bettencourt, who suffers from a degenerative form of dementia. The verdicts in that case are expected to be announced in May.

Liliane Bettencourt is ranked by Forbes as the richest woman in Europe, and the tenth-richest individual worldwide, with a wealth estimated at just under 35.5 billion euros (42 billion US dollars).

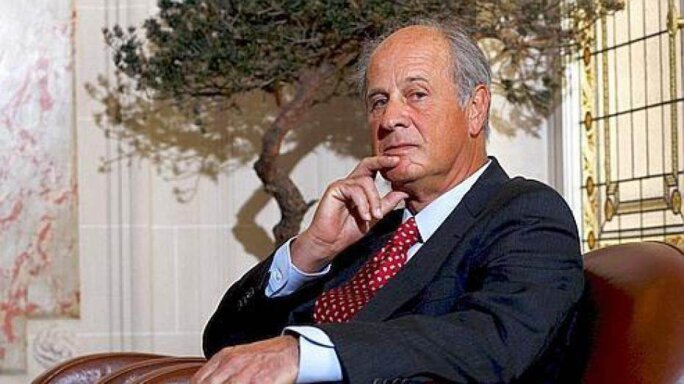

Woerth is the conservative UMP party Member of Parliament for the town of Chantilly, of which he is also mayor, and served under Nicolas Sarkozy’s 2007-2012 presidency as budget minister, then labour minister. Crucial to the case heard this week, Woerth also served as treasurer of the UMP from 2003 to 2010, and as the treasurer of Sarkozy’s 2007 presidential election campaign.

The charges of influence peddling against Woerth and Maistre centre upon the recruitment in early 2007, allegedly at Woerth’s behest, of Woerth’s wife Florence as a financial advisor for Clymène, the company that manages Liliane Bettencourt’s wealth from the dividends she receives as principal shareholder of L’Oréal, and which was headed by Maistre. Woerth, who had only known Maistre personally for a matter of months, subsequently lobbied for the latter to be awarded the Légion d’honneur, France’s highest award for civil merit. During the ceremony on July 14th 2007, it was Woerth, who had just been appointed budget minister under newly-elected president Nicolas Sarkozy, who personally presented Maistre with the honour.

Enlargement : Illustration 1

While Woerth, unlike Maistre, appears likely to escape sentencing in the first trial in February, the evidence stacked up against him in this week’s trial, which opened on Monday and closes on Wednesday, will provide a far more testing job for his lawyer Jean-Yves Le Borgne. Mediapart has gained access to the 66-page document prepared by the three magistrates who led the investigations into all the cases relative to the Bettencourt Affair, in which they detail why they sent Woerth and Maistre for trial. The detailed document dresses a damning account of illicit favours exchanged between the two men.

Under French law, investigating magistrates send their findings and conclusions at the end of a case for study by the public prosecutor’s office, which then offers its advice on whether to press charges. However, the investigating magistrates have the final word, and in the case of Woerth and Maistre, the judges - Jean-Michel Gentil, Cécile Ramonatxo and Valérie Noël – decided to send the pair for trial against the recommendations of the public prosecutor’s office.

“It seems perfectly established that, as of January 19th 2007, Eric Woerth asked Patrice de Maistre to meet his wife who wanted to give a new direction to her career, that contacts were made to that end, as of March 15th 2007, with a view to her being hired by the company Clymène, and that this recruitment occurred on November 12th 2007,” the judges write in their conclusions.

At the time in question, Patrice de Maistre had sought to recruit a young financial manager for Clymène, and had mandated Paris-based headhunting company Proway to find candidates. The salary for the new recruit was to be between 130,000-140,000 euros per year. In the event, the candidates who were presented to him were refused the job in favour of Florence Woerth, and who was granted an annual salary of 180,000 euros.

“Reciprocally, it is also established that Patrice de Maistre directly proposed to Eric Woerth, who had told him that his wife Florence Woerth sought a reorientation of her career, that he would meet her for that purpose,” the judges continued. “Patrice de Maistre subsequently allowed for Florence Woerth to be recruited outside of the procedure that had been put in place by the company Clymène through the intermediary of the company Proway, whereas Florence Woerth did not match the desired profile and that she was hired with a much larger remuneration than that initially planned. Such conditions constitute a real advantage in favour of Florence Woerth, wife of Eric Woerth.”

“It is also established that Eric Woerth had indeed, on March 12th 2007, been at the origin of obtaining the Légion d’honneur for Patrice de Maistre who had solicited him to that end. He had, however, only known him for a few months, and had only met him during brief moments. Eric Woerth proposed and transmitted the dossier for the obtainment of the Légion d’honneur while knowing that he had solicited Patrice de Maistre for advice for his wife Florence Woerth [who was] looking for a new job.”

The three judges concluded: “The link of cause with effect between the engagement made by Patrice de Maistre towards Eric Woerth to meet his wife to talk about her career, then her hiring and finally her recruitment within the company Clymène, and the benefit obtained or expected by him, namely the obtainment of the Légion d’honneur, is perfectly established by the chronology of events revealed [and] their happening, this despite the multiple denials of those concerned. Consequently, Patrice de Maistre and Eric Woerth will be sent for trial before court on these charges of influence peddling.”

'Her husband was finance minister, he asked me to do it'

Questioned during the investigation, Patrice de Maistre maintained that Eric Woerth had played no part in his nomination for the Légion d’honneur, and said that it was rather friends of his within the then-ruling conservative UMP party who had used their influence for him. Under questioning, Eric Woerth just as cautiously declared that he could no longer remember what role he played, claiming that the dossier to justify the granting to Maistre of the Légion d’honneur had already been prepared.

However, evidence seized by the judges, and witness statements given to them, illustrated the opposite. It was through Eric Woerth’s personal intervention that Maistre received the honour in 2007, while the two men had known each other only since the end of 2006. That fact is clearly exposed in a letter dated March 12th 2007 that Woerth sent to Nicolas Sarkozy. At the time, Woerth was Sarkozy’s presidential election campaign treasurer.

Enlargement : Illustration 2

It was Maistre who asked for the Légion d’honneur. A member of the conservative UMP party’s Premier Cercle club which, headed by Woerth, brings together the richest donators to the party, the investment manager appears as a man in constant search of networks, status and money. Awarding Maistre with the Légion d’honneur was clearly of importance to Woerth, who, in his printed letter to Sarkozy, added at the end of the page in handwriting: “It would be good to agree to this request. I’ll talk about it with you.”

As in the first trial in January, when 10 people answered charges of manipulating Liliane Bettencourt for personal financial gain, the transcripts of the conversations secretly taped by Liliane Bettencourt’s butler provided crucial evidence. Between May 2009 and May 2010, Bettencourt’s long-serving major-domo, Pascal Bonnefoy, recorded hours of conversations between the l’Oréal heiress and her advisors, including Maistre, using a digital Dictaphone hidden behind a chair in Bettencourt's private office in her town mansion home in Neuilly-sur-Seine, just west of Paris.

Bonnefoy later explained that he had done so to expose the manipulation of the elderly woman, who was already suffering from a degenerative dementia, by her entourage. Indeed, the conversations revealed, among other things, evidence of money-laundering, tax evasion and improper interference in judicial procedures, but also the influence peddling for which Woerth and Maistre were eventually charged.

The judges noted a passage of conversation, recorded on October 29th 2009, between Maistre and Bettencourt, who was then aged 87. The two had met to talk about a project to create an ‘André Bettencourt auditorium’, in honour of Bettencourt’s late husband, within the venerable Institut de France – which would finally never take place. In the conversation cited by the judges, Bettencourt, who also suffers from partial deafness, asked only basic questions of her wealth manager.

The passage (which below includes hesitation stops) begins with Liliane Bettencourt asking “who is this man?”:

Patrice de Maistre: “Well it’s the husband of Madame Woerth, who you employ, who is one of my staff, who’s not very tall, voilà…and…but him, he is very nice, and he’s our budget minister, and it’s he who allowed the Institute to takeover the building in which the auditorium is to be created.

Liliane Bettencourt: “No?”

Patrice de Maistre: “He’s very nice, and what’s more, it’s him who looks after your taxes, so…I find it’s not idiotic. He’s the Minister of the Budget. So there you are.”

Liliane Bettencourt: “(no clear reply)”

Patrice de Maistre: “And he’s a very nice man, he’s a friend.”

Liliane Bettencourt: “She too? Less so.”

Patrice de Maistre: “Less so. She, she pushes a bit . She tires me a little.”

Liliane Bettencourt: “Oh yes?”

Patrice de Maistre: “Yes.”

Liliane Bettencourt: “She…”

Patrice de Maistre: “She sees herself a bit as the minister’s wife.”

The judges also cite another conversation between Maistre and Bettencourt, dated April 23rd 2010, when Florence Woerth is again mentioned.

Patrice de Maistre: “I, I have…I made a mistake when I hired her. That’s to say that in fact, to have the wife of a minister like that, it’s not a plus, it’s a minus. I made a mistake. Why? Because as you are a woman, the richest woman in France, the fact that you have the wife of a minister for you, all the newspapers, all the things, say 'Oh yes, everything is mixed together'. OK, I admit that when I did it, her husband was Minister of Finance, he asked me to do it.”

Liliane Bettencourt: “Ah!”

Patrice de Maistre: “I did it to please him."

The secretly-taped conversations of that April 23rd 2010 also revealed that when Florence Woerth was finally sacked from her job in Clymène, Maistre insisted on meeting Eric Woerth to announce the move. “A little career mover,” Maistre said, describing to Bettencourt what he saw as Florence Woerth’s ambitious streak. “And so she is here, and voila,” Maistre said. “Right, and if you like, today, without making any noise, with the trial and with Nestlé, we must be very manouevering, and we can no longer have his wife. And then we, then we will give her money and voilà. Because it’s too dangerous.”

A curious delay in the case

Patrice de Maistre and Eric Woerth first met at a cocktail party given by the UMP party’s big-money donors' club, the Premier Cercle, at the end of 2006, when Maistre was Liliane Bettencourt’s wealth manager and Woerth treasurer for both the UMP and for then-interior minister Nicolas Sarkozy’s campaign for the May 2007 presidential elections. In this context, their several subsequent discreet meetings during the run-up to the official launch of the presidential election campaign, along with the evidence that has been heard suggesting cash payments were passed by the former to the latter, as well as the officially-declared funds given to the UMP by Maistre and Liliane Bettencourt and her late husband André, who died in November 2007, have a clear sense: the alleged influence peddling – the hiring of Florence Woerth in exchange for the Légion d’honneur – appears less of a simple, one-off event of backscratching, but more as an illustration of a larger, opaque system.

According to Woerth’s own documents, handed over to the judges during the investigation, the Bettencourt couple, between 2003 and 2010, made six donations to the UMP totaling 35,200 euros, as well as donating 7,500 euros each to a political support committee for Nicolas Sarkozy, called the Association in Support of the Actions of Nicolas Sarkozy (à l’Association de soutien à l’action de Nicolas Sarkozy) at the end of 2006. In March 2010, just less than three years after Sarkozy was elected as French president, Liliane Bettencourt also contributed 7,500 euros to another support committee in favour of Eric Woerth – the no less awkwardly-named the Association for Funding the Association of Support for the Actions of Eric Woerth (l’Association de financement de l’association de soutien à l’action d’Éric Woerth). All of these officially-declared donations represent perfectly legal practices.

But in the judges’ summary of the reasons for sending the two men for trial, they refer to their investigations into the suspicion that Maistre and Woerth were involved in secret and illegal political funding. “The investigations carried out did not allow to establish either the destination of these funds, or their acceptance at any date by a political party, by an association in support of the action of a political figure or by an association for the financing of this action.” Thus, potential charges of “illicit financing of a political party, of the illicit financing of an electoral campaign, of complicity and handling in these crimes” were definitively dismissed by the magistrates.

But the judges dismissed earlier arguments presented by the public prosecutor’s office for recommending that all charges against Maistre and Woerth be thrown out, and they also ruled as invalid the prosecutor’s claim that in any event, the illegal political funding suspicions in the case were subject to a statute of limitations that meant they could not be prosecuted even if the judges had wanted to pursue the matter.

The public prosecutor’s office, in its own summary of the case against Maistre and Woerth, noted that “the proof of cause and effect between the recruitment of Florence Woerth and the awarding to Patrice de Maistre of the Légion d’honneur has not been possible to formerly establish.”

It added that “quite more certainly, the support given by Eric Woerth to the candidature of Patrice de Maistre [for the Légion d’honneur] could be an expression of gratitude for his diligent involvment in politics, notably expressed on a substantial financial level”.

“However shocking it may be on a moral level, this other posibility – which was not envisaged under the terms of the placing under investigation of Eric Woerth and Patrice de Maistre and which concerned events today covered by the statute of limitations – opens up a degree of doubt that is the benefit of those concerned.” On the second day of the trial on Tuesday, public prosecutor Gérard Aldigé called for the charges to be thrown out.

Meanwhile, the judges included in their document an interesting observation that appears to imply a suspicion of undue interference in the judicial process of the Bettencourt affair. The initial investigations were led by Judge Isabelle Prévost-Desprez in the jurisdiction of Nanterre, close to Paris, but the openly conflictual relationship between her and the Nanterre prosecutor Philippe Courroye prompted a decision by the Paris appeal court to transfer the case to the judges in Bordeaux. In their summary, the judges noted that that decision was taken on November 17th 2010, but that the case files only arrived in Bordeaux on December 15th 2010 “being almost one month after the designation of our jurisdiction”, they wrote, “and the day that followed when Eric Woerth recovered his parliamentary immunity”. That referred to the fact that Woerth, who had been forced to step down as labour minister – a post he took over after serving as budget minister – returned to the national Assembly in his position as Member of Parliament (MP) for Chantilly. Under French law, MPs cannot be subjected to any legal move to restrict their movements, and notably that of preventive detention.

The verdicts in the trial this week will be announced in the coming weeks, and possibly as late as May. Eric Woerth’s more-than 30 years in active politics is in the balance, as is Maistre’s continuing career in finance. If found guilty of the charge of influence peddling, the maximum sentence they each face is ten years in prison and a fine of 150,000 euros, as well as being stripped of their voting rights and the right to hold public office.

-------------------------

- The French version of this article can be found here.

English version by Graham Tearse