“The problems of corruption and Mafia-like crime appear to have been erased from the agenda of political parties,” wrote Italian public prosecutor Roberto Scarpinato in the opening of his 2008 book Il Ritorno del Principe (The Return of the Prince). “Corruption has disappeared under a concrete floor, even though its irrepressible proliferation has a global cost that is evermore insupportable for the country.”

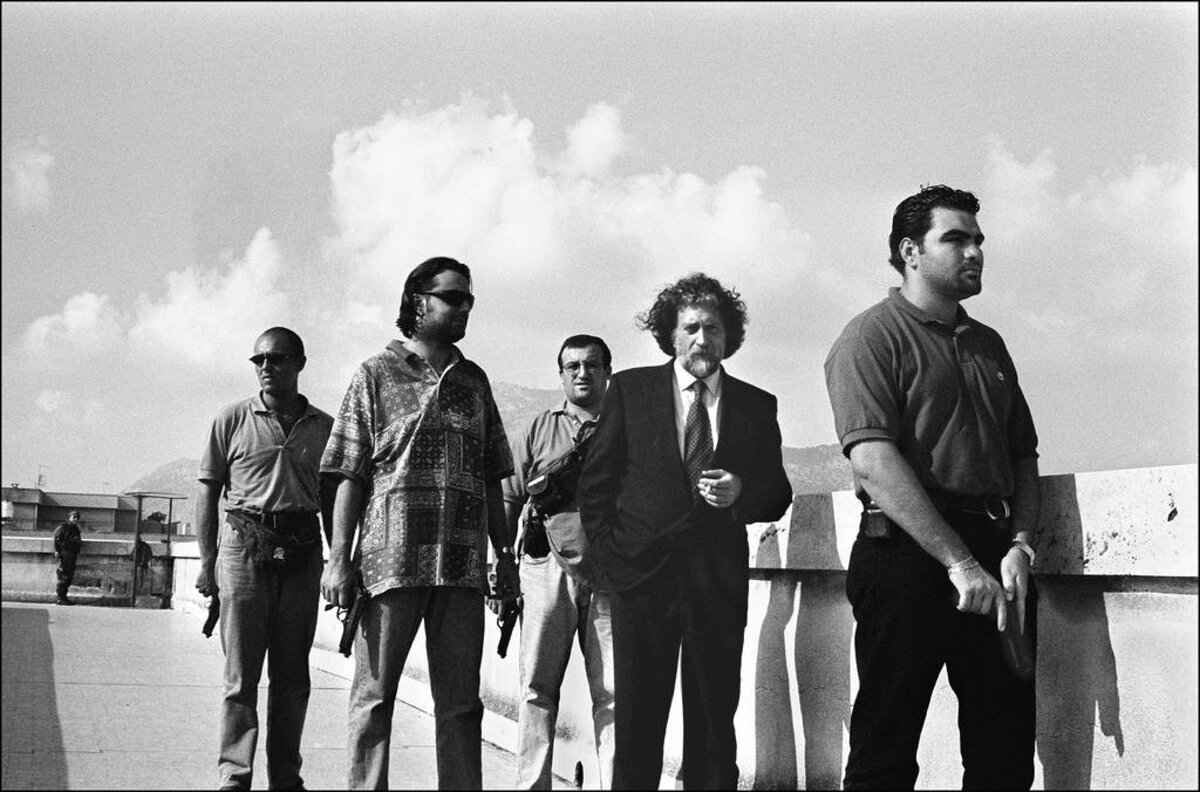

Enlargement : Illustration 1

It suffices to read those two lines to understand why the decision to invite Roberto Scarpinato’s as a speaker at the public debate, organised in association with Mediapart, in Paris on October 19th, entitled ‘Corruption ça suffit’ (Enough of Corruption), was an obvious one.

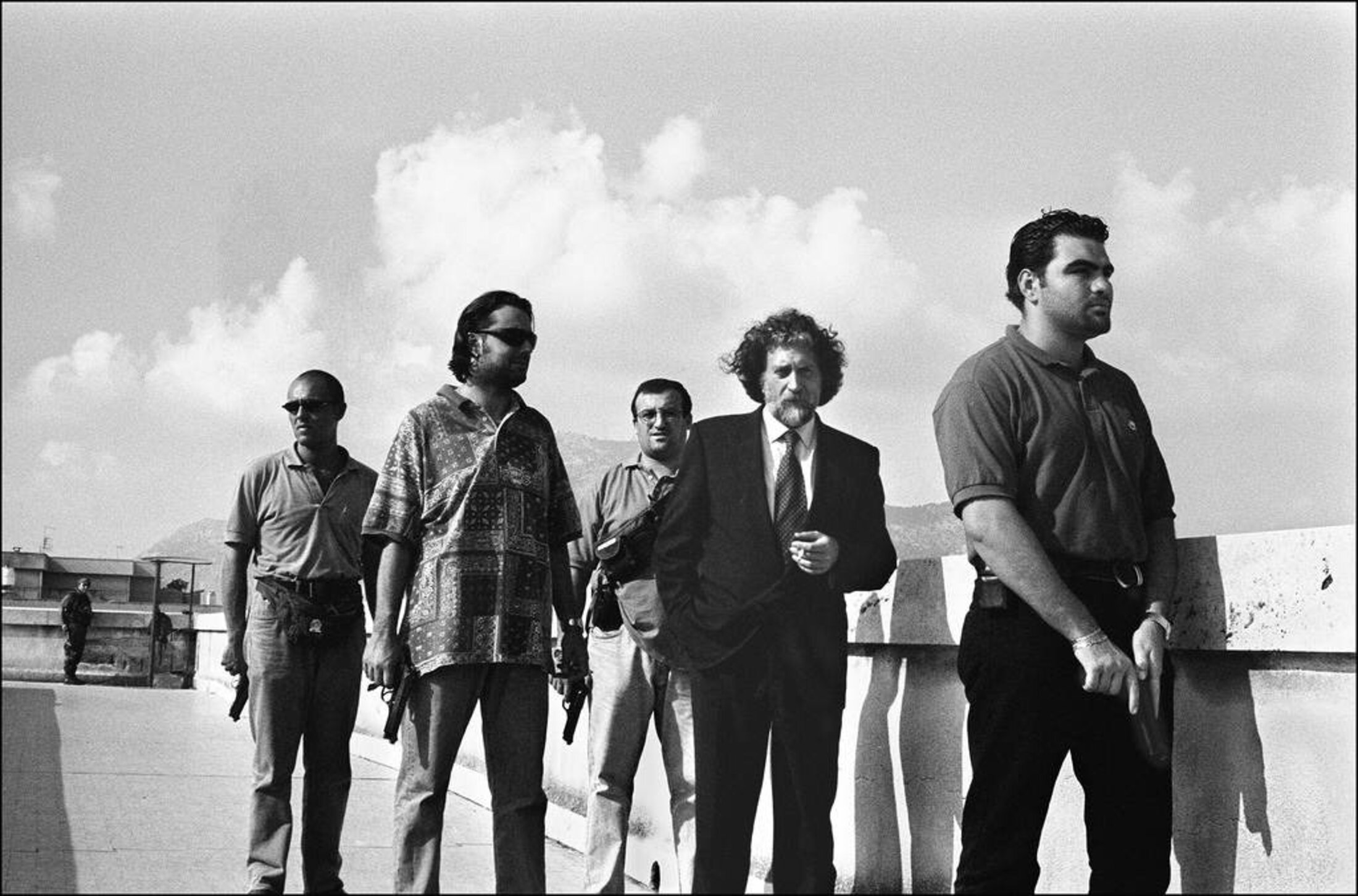

Enlargement : Illustration 2

The debate brought together representatives of diverse professions, including journalists, magistrates, lawyers, police officials, economists, sociologists and thinkers who, at the end of the evening of discussion, launched a public appeal and petition for effective action against corruption.

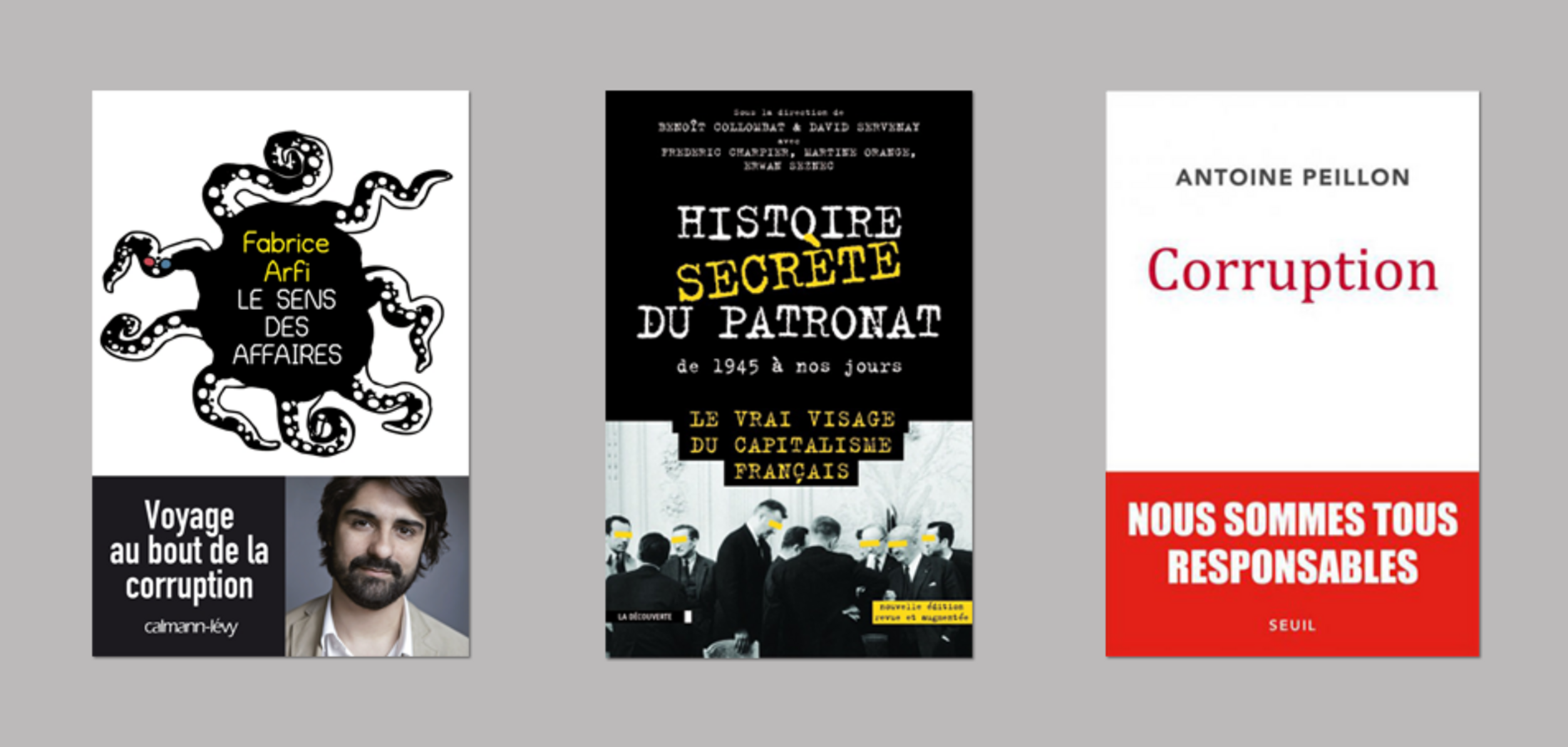

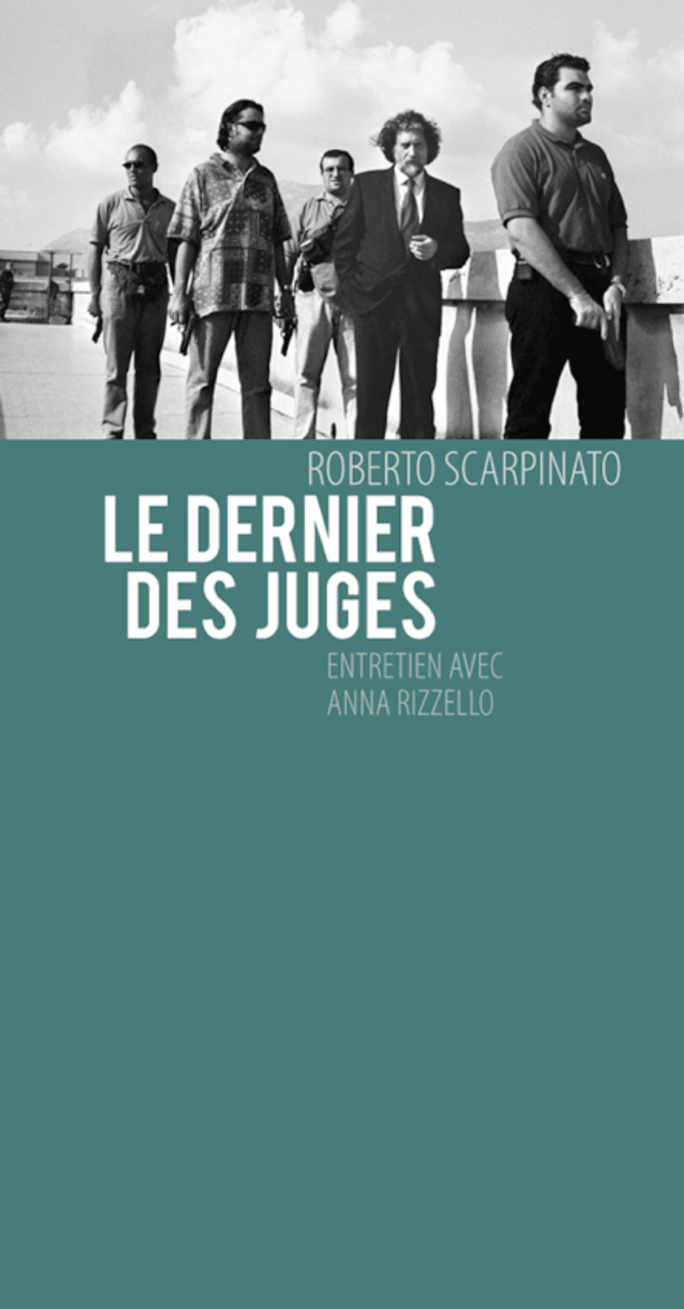

A former colleague of murdered Italian anti-Mafia investigating magistrates Giovanni Falcone and Paulo Borsellino, both assassinated in 1992 within 57 days of each other, Scarpinato is now a senior magistrate with the public prosecutor’s office in Palermo, Sicily. Living for more than 20 years with a permanent police escort, his investigations have unveiled the links between the ‘lower’ Mafia of the traditional, violent organised crime mobs, and the ‘upper’ Mafia of ‘respectable’ society, where business dealings dove-tail with political arrangements, a system in which the former is subordinate to the latter.

Born in 1952, Scarpinato is also a man of his generation, loyal to the democratic, social and moral aspirations of his youth, to the point of envisaging his profession, in an Italy where the public prosecutor’s office is independent of the political powers, as an engagement.

Scarpinato is the living symbol of what the three initiators of the debate (journalists Fabrice Arfi from Mediapart, Benoît Collombat from France Inter radio and Antoine Peillon from daily newspaper La Croix) had wanted to do. That is, to place the issue of corruption at the top of the political and media agenda, to measure the damage it causes and its banalisation, and to prompt a movement of resistance and revolt in face of this scourge that saps our democracies. With the simultaneous publication by each of books which share a common view, Arfi, Collombat and Peillon opted for solidarity rather than competition by joining together to give a greater echo to what they reveal. Namely that corruption is not a marginal issue, but is at the heart of a system which has promoted money and power as the only values of reference.

Enlargement : Illustration 3

Roberto Scarpinato discovered this before them, and it was a painful experience. “Do you know what’s written in the Ecclesiastes? He who increases his knowledge increases his pain.” That comment by Scarpinato is cited by his French translator, Anna Rizzello, writing in the introduction to Le Dernier des juges (The Last of the Judges), a book of conversations between Scarpinato and her, published in France in 2011. “He knows, and this knowledge has changed his life irrevocably,” she wrote. “The pain of knowing is engraved on his face, and in his gestures.”

With his keen interest in classical culture, Scarpinato recalls, in the opening of his book The Return of the Prince, that the oracles of ancient Greece were often blind, as in the case of the best known among them, Tiresias. “To reach the essential, it is necessary to make oneself blind to the inessential,” explained Scarpinato.

It is in this manner that veritable justice and authentic journalism are in part joined together. Concerning us, the latter, this is about uncovering information of public interest and avoiding attention upon diversionary trivia.

'The vocations of heroes and martyrs is rare these days'

Indeed, everything is done to prevent us seeing properly, that is, to identify what’s essential. Far from this being a new feature of our societies marked by the immediacy and superficiality of the media, it is an old tactic employed by every dominant power. Cardinal Jules Mazarin, a Jesuit of Italian origin who served as Chief Minister of France and who was close advisor of the Sun King, Louis XIV, once commented that “the throne is won by swords and canons, but it is kept by dogmas and superstitions”.

Scarpinato believes he has found the most explicit theorisation of this system of dominance, and there is no shortage of irony here, for it is a text written by Joseph de Maistre 1753 - 1821, a French count and counter-revolutionary, who is the ancestor of Patrice de Maistre, the former wealth and investment manager of L’Oréal heiress Liliane Bettencourt, and who will next year stand trial on corruption-related charges (see more here). “If the governed crowd can believe itself to be equal to the small number that governs, there is no longer any government,” wrote Joseph de Maistre. “Power must be beyond the understanding of the crowd who are governed. Authority must be constantly kept above critical judgment, through the psychological instruments of religion, patriotism, tradition and prejudice.”

To fight corruption is also to unravel and unmask such a strategy. That is why what is at stake with this fight is not only judicial but is fundamentally political. Corruption is at the service of a cultural system in which a distance is kept between the governors and the governed, just as also between those who possess and those who are exploited. In short, it is one which isolates, disarms and disorientates the people because this distance relies on a situation of incomprehension, a confusion of bearings and the lowering of ideas.

“Every path towards liberation, both personal and collective, implies a process of de-structuring of the cultural impostures which impregnate our lives from the youngest age,” comments Scarpinato towards the end of The Last of the Judges. “That is why the battle to build a [system of] political power that is at the service of men, and not over men, necessarily involves the field of knowledge. As long as we don’t create knowledge that is free of the chains of political power, the latter perpetuates itself, equal to itself, maintaining individuals within an illusion that they are determining themselves in an autonomous manner.”

From journalism to the judicial services, this battle for knowledge, against its confiscation by those who hold power and wealth and who are sheltered by secrecy and lies, is decisive. It is decisive in order to restore politics to being for the common good, and to encourage the renewal of politics, from the base to the top. Otherwise we will be left to live under the reign of an oligarchy disguised as a democracy, and it will be our own fault: through indifference towards corruption, by tolerating its amorality, and by keeping silent in face of the damage it wreaks (the stealing of assets, the disregard of principles, the acceptance of servitude, the toleration of impostures, and so on).

Enlargement : Illustration 4

To make this better understood, to the point of becoming aware that what is at stake here is not only essential but also eternal, Scarpinato looked back in time. In this exploration, he demonstrates to us that while there may be differences, according to a given period, in the violence employed, there is no difference in nature between the tactics of criminal organizations and those of oligarchs.

The word imposture has its roots in the Latin verb imponere, meaning to impose. Scarpinato points out that in ecclesiastic language, imponere at times designated the act of making someone hold a belief by using deception. “The history of power, including in its criminal form like the Mafia, corruption and terrorism, could therefore be re-written as being an account of a journey in the kingdom of imposture, the land of the construction and perpetuation of false beliefs that are useful for the maintenance of power,” observes Scarpinato.

He underlines that the word obscene has its roots in the Latin ob scenum, indicating something that is out of the scene. Out of the scene and thus not part of the setting. “Veritable power is always obscene,” says Scarpinato. To unveil this obscenity is the most effective way of shaking it, in a strategy of the weak before the strong, a revelation that causes surprise, revulsion or indignation. In other words, to reveal what is off-scene in order to smash the code of silence which allows those with power to escape the shame of revelation. Shame in Italian is vergogna, from the Latin vereor gogna for “I fear pillory”.

As has already been illustrated in France by the Bettencourt affair, including the imposition of censorship, and as is illustrated today by Nicolas Sarkozy’s campaigns of stigmatization and discredit targeting magistrates and journalists, the question of true fact, concrete and material, that of witnesses, of documents and recordings, is decisive - and therefore the most disputed – in this path towards justice upon which the powers that be are threatened with being uncovered.

Scarpinato explains this in one of the rare passages where he refers to his experience as a public prosecutor, and with the sadness of he who has seen and heard the obscene. “The vocations of heroes and martyrs being rare these days, only the machines, from time to time, break the artificial silence with which power is surrounded,” he says. “When the results of criminal trials are made public, the recordings from spying microphones and phone taps allow citizens without power to hear, directly and without censorship, the secret voice of power. And it’s like lifting a piece of a curtain and seeing a degrading reality, behind all the whitened sepulchres that line the front of the scene.”

Those who believe in only power and money

Just like his compatriot Roberto Saviano, journalist and author of a book about the Mafia, Gomorrah, Scarpinato cautions us against concluding that there is a reduction in Mafia-like criminal activity because there is less visible violence perpetrated by the ‘lower’ Mafia, that which is anchored in social misery and despair. “The Mafia method is losing its visibility, not because it is disappearing but because it is propagating,” he writes, slamming the “media vulgate according to which the Mafia is nothing but a rotten criminal business featuring sawn-off shotguns and the dissolving of corpses in acid.”

“Mafia-like association is characterised by its particular finality,” Scarpinato underlines, citing the Italian code of law, “which does not consist of simply committing crimes, as is the case of ordinary criminal association, but in illegally conquering spaces of power, economic and political in particular.” The “finality” in question requires a means which is “this obscure ill which gnaws at those in power”.

In his exceptional maieutic, Scarpinato cites Tiresias, the blind but clairvoyant prophet of Greek mythology when he provlaimed “The offense against the truth was the origin of the disaster.” Scarpinato recalls that in Sophocles’ tragedy Oedipus Rex, the tyrant of Thebes questions Tiresias as to the whereabouts of his father’s killer, whose continued freedom is reportedly the cause of a plague in the town. “The assassin who you seek is you,” Tiresias tells Oedipus. It is a manner of telling us that in face of corruption we will all be the assassin if we continue to look at the inessential and ignore the essential. Otherwise put, we would be complicit in a ‘Mafiasation’ of the world, that spreads under the cover of our indifference and passivity.

Roberto Scarpinato is one of the exemplary ‘just’ who won’t resign themselves to this. He has made a personal motto of the ancient Greek maxim “Live today as if you were to die tomorrow, but think as if you were eternal”, a saying that he considers to be “the apogee of human wisdom”. On July 19th 2012, he enacted that motto when he made a rare public appearance to render homage to his late friend and colleague Paolo Borsellino, 20 years to the day after he was murdered in a car bomb explosion in Palermo.

Scarpinato’s speech was in the form of a direct address to his late colleague, and he began right away by exclaiming his surprise at the presence of, “in the front rows, in the places reserved for the authorities, personalities whose behaviour appears to be the very negation of the values of justice and equality for which you were assassinated”.

“Equivocal personalities past and present whose lives give off, to use your words, this stink of moral compromise that you reviled so much and which opposes itself to the fragrance of liberty,” continued Scarpinato, who implored them to have the grace of keeping quiet, if not to stay away. “You who believe in nothing other than the religion of power and money, and who are not capable of rising above your petty personal interests, keep quiet on July 19th, because this day is dedicated to the memory of a man who sacrificed his life so that words like State, Justice and Law had at last a meaning and a value in our poor and unfortunate country.”

In this moving speech, Scarpinato underlined the great contribution to democracy of magistrates Paolo Borsellino and Giovanni Falcone, a past that is so very much relevant to the present.

“You and Giovanni [Falcone] had above all been extraordinary creators of a sense. You have accomplished the historic mission of handing the State to the people, because it is thanks to you and men like you that, for the first time in the history of our country, the State presented itself with credible features to which it was possible to identify oneself, and to say ‘the State is us’ took on meaning,” he said. “You taught us that, to build together this grand Us which is the democratic State of law, it is necessary that each and everyone rediscovers and cultivates the capacity to fall in love with the destiny of others.”

“They underestimate you Paolo,” continued Scarpinato, “because you taught us something much bigger. You taught us that the sense of duty is nothing much if it is reduced to the detached and bureaucratic execution of our tasks and to obedience towards our superiors.”

Roberto Scarpinato ended his homage by pledging to “discover the truth”, meaning about that of the “obscure and powerful forces” who are hidden behind the hand of the killer. He kept his promise. After having been summoned before the Italian high council of magistrates in reprimand for his strong speech, and subsequently cleared amid widespread popular protest, and after having been appointed as public prosecutor (attorney-general) in Palermo by the very same council in early 2013, he recently launched proceedings against a former Carabinieri general and colonel for their links with the Mafia.

Shortly after, he found a letter placed well in sight in his office (which is in theory as inaccessible as a nuclear bunker) threatening him, and which was as well-written as it was well-informed. There was no trace of an intrusion on the images recorded by the surveillance cameras. Nothing, no clue, in the manner of making it understood that the threat lies at the closest level, from inside the State itself and the oligarchy that has appropriated it.

-------------------------

- The original French text of this article can be found here.

English version by Graham Tearse