The Ecole Bilingue Active Jeannine-Manuel (EABJM) is a unique and sought-after Paris school that offers the offspring of the rich, famous and powerful an elite educational training and the chance to later become part of an international club of professional high-flyers.

This semi-private school in the 15th arrondissement of Paris specialises in teaching in both French and English, from the pre-school entry class for three year-olds right through to the school-leaving Baccalauréat exam. It was recently classified in daily La Tribune as the third-best lycée [1] in France after Henri IV and Louis-le-Grand, the state high schools in Paris which regularly get the top ratings.

The sons and daughters of political figures like former president Nicolas Sarkozy, the head of his conservative UMP party, Jean-François Copé, or captains of industry like Arnaud Lagardère or the Dassault family that owns the aviation company of the same name, have all rubbed shoulders there. Parents fight tooth and nail to find a place for their children who – even when aged three years-old - must pass a test to be admitted.

Not only is there bilingual English-French teaching from pre-school onwards, but pupils also start learning Chinese at age 8 in the junior section of the primary school.

The school boasts a 100% pass rate at the Baccalauréat, and the latest results showed 96% of its pupils who sat the exam received its highest award, a "mention". The premises are impressive, with a 1,500 m2 science building, a theatre and a spacious arts room. There are cultural outings, a range of after-school activities – practically unheard of in the French state system – and school trips to China or Japan.

The school, like most private schools in France, operates under a system known as a ‘contract with the state’, which means it receives a public subsidy in return for fulfilling certain conditions, which include teaching the French national education syllabus. But unlike most private schools in France, which are managed by the Catholic Church [2], it is secular. The subsidy helps keep fees lower than at similar establishments in other countries – parents pay 4,500 euros per year to send their children to the EABJM, whereas elite British private schools usually charge more than that per term [3].

Its status allows the school to combine different teaching methods with a traditional French approach. "On the Anglo-Saxon [4] side there is an active pedagogy, and on the French side the solidity of the syllabus. EABJMis a mixture of both," the school’s deputy head, Florence Bosc, wrote in an internal document.

Other attributes include a debating club, set up to help pupils who have difficulty speaking in public develop this ability – important for the oral exams that form part of the Baccalauréat – and also lunches organised for the school’s exceptionally gifted pupils to discuss their difficulties.

Teachers offer a comparatively unusual degree of availability. One teacher at the school, whose name is withheld here, said he constantly receives e-mails from parents, sometimes until 11 p.m. "I am supposed to reply to them as quickly as possible otherwise I will be in trouble," he said.

But at EABJM parents are paying for more than an elite education. Their children are also introduced to a web of influential international contacts. "It is true that the economic power of parents is well above the average and, at the end of the day, on the pretext of an opening onto the world we are preparing an international network for our children," commented one parent in the December bulletin of the school's Parents’ Association.

-------------------------

1: Lycées take pupils aged 15-18 to study for the Baccalauréat, the French school-leaving examination.

2: In France, 17.5% of school students are enrolled in private schools. Of these, 98% attend schools run by the educational arm of the Catholic Church, l’Enseignement Catholique.

3: By comparison, for the 2012/2013 school year, day pupils at Shrewsbury School in Britain pay £6,860 per term, or £20,580 a year (about 25,220 euros). Eton, the school attended (among others) by British Prime Minister David Cameron, charges £10,689 per term or £32,067 per year (roughly 39,290 euros), although this includes the cost of boarding.

4: In France, the term 'Anglo-Saxon' is widely used to describe what is Anglophone.

A cause 'in the general interest'

As if to illustrate this point, Bernard Manuel, son of the school’s founder and also chairman of the EABJM Association, had this to say in a promotional video: "Four of our former pupils who happened to be in the White House cafeteria noticed they were all speaking French." When they inquired as to how come the others spoke the language, he continued, they discovered they had all been pupils at EABJM in Paris.

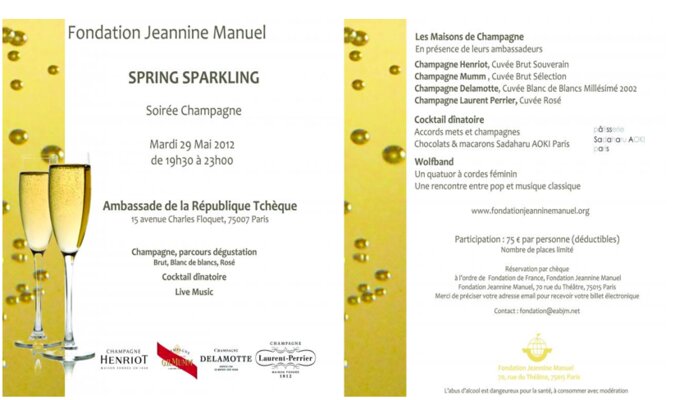

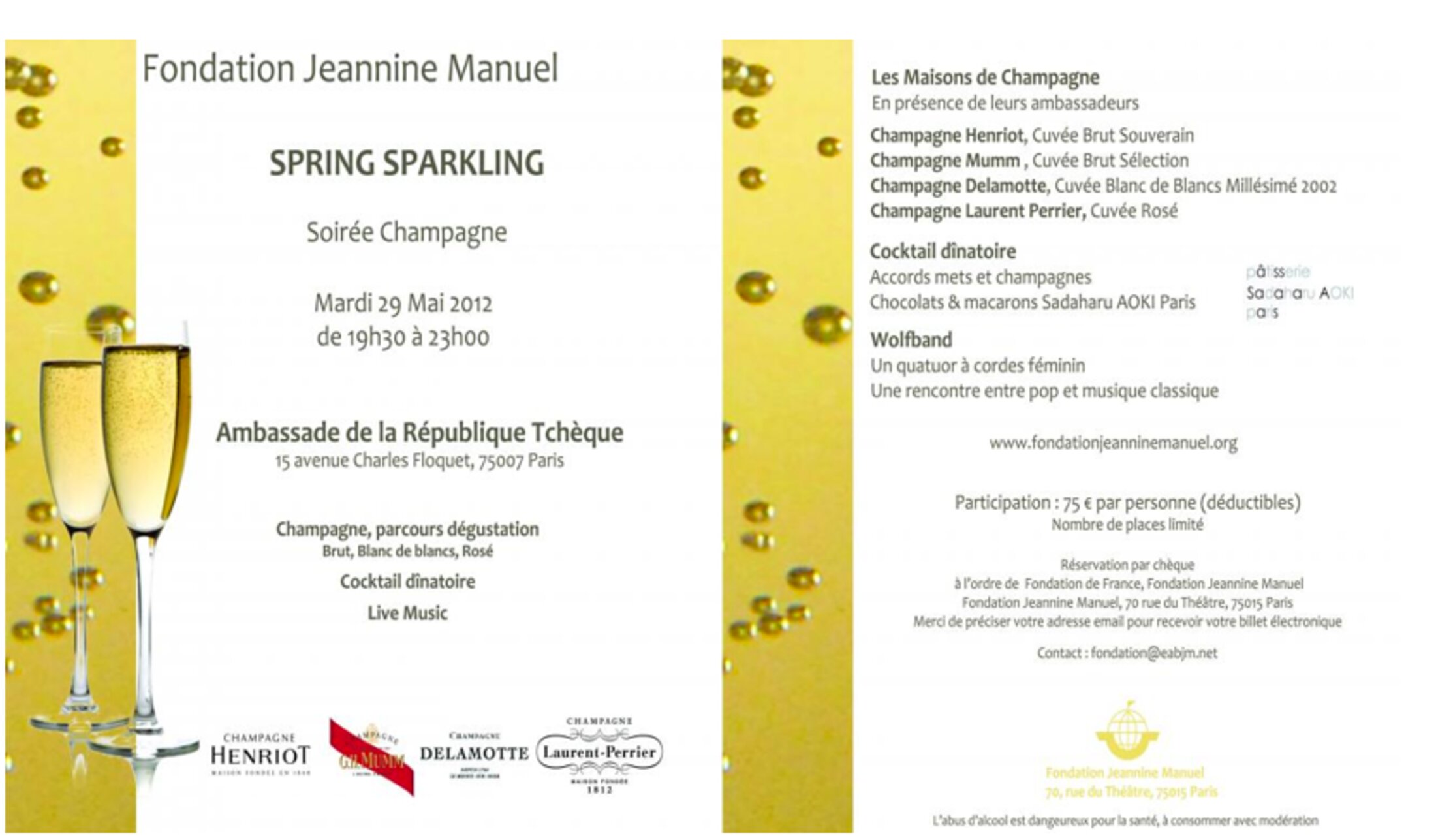

And to keep this networking alive, the school organises glamorous events. Last May it held a champagne evening at the Czech Republic’s Paris embassy, and it finished 2012 with its swish annual gala in the salon d’honneur at the Grand Palais museum in Paris. This was a charitable event to raise cash for the Jeannine Manuel Foundation.

Enlargement : Illustration 2

The Foundation, set up in 2004 to "promote international understanding through bilingual education", raises significant sums of money from donors, who are usually also parents of pupils at the school. It comes under the auspices of the Fondation de France, and its statutes give it a considerable advantage; the money it collects is eligible for a 66% tax reduction.

Headmistress Élisabeth Zéboulon justifies the school’s fund-raising efforts on its website. "Without innovation, this school would no longer be able to live,” she notes. “So if we want this school to continue to live, to progress, to have multiple projects, well then, we must find ways to finance it."

Zéboulon reportedly earns a monthly income of close to 18,000 euros, equivalent to almost three times the salary of the head of a state-run university in France. This is made up of both her salary as headmistress and also as the manager of a company, called Remi, which sells learning books, published in several languages, to the school’s pupils.

The Grand Palais gala began with an auction presided by Pierre Cornette de Saint Cyr, head of the eponymous auction house. "Parents bring the lots – paintings, furniture – and the participants bid," said a person who regularly attends these events, whose name is withheld here. The evening ended with a disco dance organised by musician, stylist and DJ Béatrice Ardisson, a school parent whose ex-husband is a prominent French television show host.

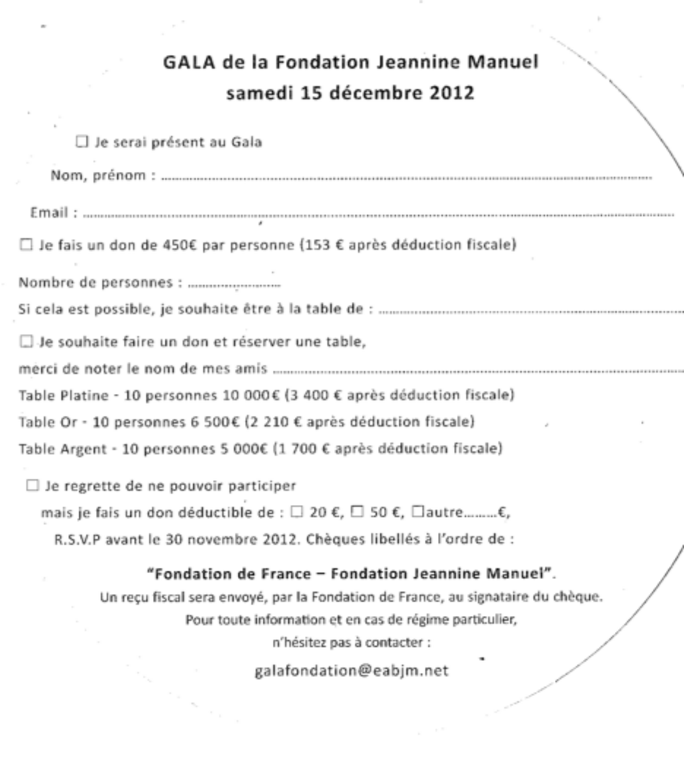

The ticket for dinner cost 450 euros which, as the invitation was at pains to point out, came to only 153 euros after tax deductions. There was also a "platinum" table for ten priced at 10,000 euros, but after being subsidised by the taxpayer this would only cost them 3,400 euros (just as a "gold" table at 6,500 euros came to 2,210 euros after deductions). All donations made during the gala were eligible for the same tax break.

According to the Fondation de France, which acts as the guarantor of the Jeannine Manuel Foundation’s accounts, there is nothing untoward about this. "Supporting the teaching of excellence is a subject in itself,” said Dominique Lemaistre, donations director at the Fondation de France. “It has benefits throughout the country. It is important to promote bilingual education when language teaching in France is struggling." In France, charitable work in education tends to be oriented only towards social issues, she added.

As to whether there are more urgent causes for the fiscal system than that of helping the most privileged people with their private education, Lemaistre argued: "Fiscal law puts all causes in the general interest on the same level. We think it is dangerous to try and prioritise causes."

The Jeannine Manuel Foundation is not under any obligation to provide further information, nor even to publish an annual report. Foundations appear to escape the terms of a law passed in 1991 which brought in transparency requirements for associations seeking donations from the public following a scandal over misuse of funds by French cancer charity ARC.

Positively discriminating

While the school's science and arts building cost 7 million euros, of which 1 million came from the Jeannine Manuel Foundation, the Fondation Lagardère financed the building of a theatre. According to information obtained by Mediapart, the 600,000 euros it spent to equip the theatre was also eligible for a 66% tax reduction. Contacted by Mediapart, the Lagardère Foundation said it had "a problem with its archives" and could not confirm this. The latest addition to the school, paid for via the Jeannine Manuel Foundation, was the construction of an impressive climbing wall.

Two years ago the Foundation launched what is described as "a magnificent project" called ‘Grandir ensemble’ (Growing up together). Mirroring a programme inaugurated by the elite Paris political sciences faculty, Sciences-Po, which 11 years ago opened up places specifically for students from educationally deprived areas, the EABJM’s ‘Grandir ensemble’ programme sought to diversify the social layers from which it recruits pupils.

But since its launch, only two pupils from socially modest backgrounds have been admitted into the primary school entry class. Lemaistre at the Fondation de France said this was because the project is recent. "They need to be given time," she said.

However, another explanation was offered by a source at the school, who spoke to Mediapart on the condition that their name is withheld. "They tried to forge partnerships with schools in the suburbs but they were turned down,” said the source. “Strangely enough, the idea of selecting a child from Créteil and bringing him or her to the posh part of town by taxi every morning and taking them home in the evening, all in the name of social mixing, they didn’t like it much.”

The school then began to look for children who could bring it a better social balance among the population of the Paris district in which it is based. The school’s deputy head, Florence Bosc, who is also the Foundation’s development director, said in an interview with the Parents' Association that the potential pupils it sought "must have very high ability, be from immigrant backgrounds and come from underprivileged families." Several stages of selection were undertaken in the local pre-schools, following which the children then had to take a WPPSI intelligence test and a test of their speech and language capabilities.

-------------------------

See more Mediapart English articles on education issues in France:

- How Sciences-Po management clan spent public funds on behind-doors pay hikes and perks

- Defining France's 'school of tomorrow'

- French schools' study tackles discrimination taboo

- How French school books keep it a man's world

- Shelved report reveals true picture of France's 'schools of excellence'

- 'Fed up and ready to change jobs': how French teachers see the crisis in education

-------------------------

English version: Sue Landau

(Editing by Graham Tearse)