The fate of French Prime Minister François Bayrou appears sealed. Following his surprise announcement at a press conference on Monday that he will submit his government to a vote of confidence by Members of Parliament (MPs) on September 8th, it is certain that, save for a most unlikely turn of events, Bayrou will be shown the door.

The centre-right prime minister was already facing a likely defeat of his government’s draft legislation for the 2026 national budget, due to be debated in parliament in October, when an inevitable vote of no confidence would also have precipitated his departure. He faces fierce opposition to the steep cuts he has announced in public spending, and notably the axing of two of the country’s 11 public holidays, in his quest to reduce yearly public spending by 43.8 billion euros.

Bayrou has justified the spending cuts in repeated public warnings over the “gravity” and “immediate danger” of France’s huge public debt, which in 2024 stood at more than 3,305 billion (3.3 trillion) euros, representing 113.2% of its Gross Domestic Product (GDP).

In his announcement on Monday, Bayrou said he was calling the confidence vote as a “first stage” ahead of presenting his draft budget legislation. “The first stage [is] that we come to an agreement on the gravity of the situation and the urgency,” he said. “If there is not this minimal agreement, there’s no point, we won’t get there.”

“That day [September 8th], I will engage the responsibility of the government in a policy speech,” he said.

In all political logic, Bayrou will lose the vote, in which case the constitution demands that he leave office. Such a scenario will plunge France deeper into the political chaos created by President Emmanuel Macron’s decision in 2024 to dissolve parliament following the success of the far-right Rassemblement National party in European Parliament elections in June that year, when his own party was roundly defeated.

Macron justified the snap general elections as a means of clarifying the political situation, believing that the electorate would in a national poll shy away from handing the far-right the same success it garnered in the European elections, regarded by many as unimportant. But he was spectacularly wrong; the result saw the far-right become the largest single party in parliament, and the leftwing Nouveau Front Populaire coalition of the radical-left, socialists, communists and greens, outstripping the number of seats of Macron’s centre-right party.

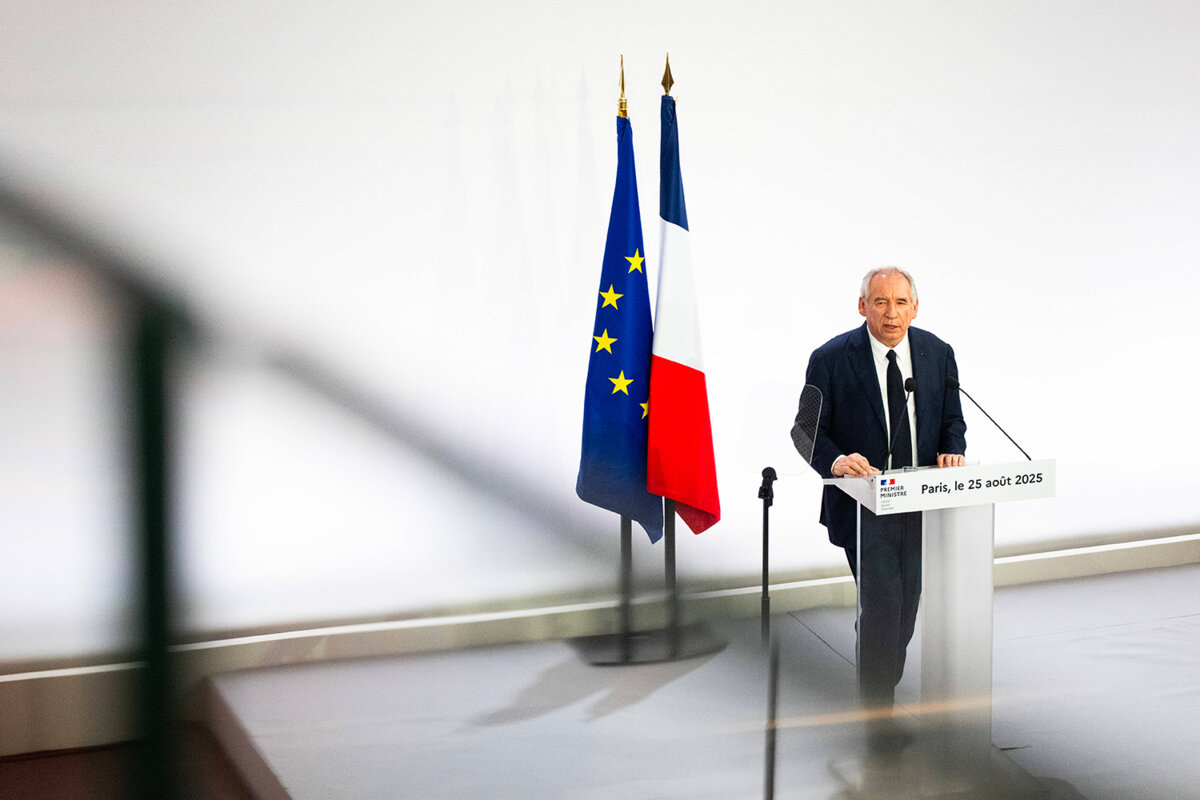

François Bayrou in an impasse

Ruling with a parliamentary minority, unpopular within his own camp and even more so among the public at large, and facing a day of strikes and protests on September 10th over his proposed budget cuts, Bayrou, 74, whose own future is chained to that of his draft budget legislation, knew he would fall with it.

Mayor of the south-west town of Pau, his political fiefdom, Bayrou, leader of the centre-right MoDem party, a doyen of parliament, which he first entered in 1986, and who twice served as a minister, has had a turbulent eight months as prime minister, with an IFOP opinion survey in July recording a record level of public dissatisfaction with a prime minister, at 81%.

After a summer of reflection, this longstanding ally of Emmanuel Macron decided to accelerate what would have been, whether sooner or later, his inevitable departure, given the nature of France’s hung parliament. It is an exit dressed in the togs of the democratic procedure of a vote of confidence, in contrast to his three predecessors under Macron’s second term – Élisabeth Borne, Gabriel Attal and Michel Barnier – who instead by-passed parliament to establish laws by decree.

Enlargement : Illustration 1

Very soon after Bayrou’s press conference on Monday afternoon, the far-right announced its voting intentions. “We will obviously vote against confidence in the government of François Bayrou,” said far-right figurehead Marine Le Pen, whose Rassemblement National party (RN) has 120 seats (123 with its allies) out of parliament’s total of 577. Le Pen, leader of the RN parliamentary group, has until now saved Bayrou by ordering her party to abstain from nine no confidence votes prompted by the parties of the Nouveau Front Populaire (NFP) leftwing coalition. But Bayrou’s unpopularity among the far-right electorate has reached a level so high that changing tactics became an obligation for Le Pen.

Parti Socialiste (PS) first secretary Olivier Faure also announced on Monday evening that it was “unimaginable” that his party would vote in favour of confidence in the prime minister, but it took until Tuesday morning for Boris Vallaud, leader of the PS group in parliament, to clearly announce that all of the party’s 66 MPs would vote against the government. The spokesman for the group, Arthur Delaporte, underlined that Bayrou had made no attempt to contact Faure during the summer recess to explore the possibility of negotiations over the budget.

Some among the ranks of Bayrou’s centre-right MoDem party, allied since 2017 to Macron’s renamed, centre-right party, Renaissance, were, in public at least, loyal to Bayrou’s stand. “There are a certain number of socialist MPs who will hesitate,” forecast MoDem MP Erwan Balanant, referring to the official announcement by the PS that it will oppose the confidence motion. “They could still abstain, everything will depend on the days to come.” Ludovic Mendes, spokesman for the Ensemble centre-right parliamentary coalition that includes both the Modem and Renaissance parties, applauded what he said was a “courageous act” by Bayrou, adding that “between now and September 8th lots of things can happen”.

Bayrou has thrown us under the bus .

But apart from the loyal few, no-one in the centre-right camp have any doubts about the outcome for the prime minister. “I don’t understand the press who continue to talk about a ‘gamble’ or who make believe that Bayrou is going to come through,” said one MP close to the Renaissance parliamentary group’s leadership, and who spoke on condition his name is withheld. “What he has done is a bloody selfish political suicide,” he said. “There was a mousehole [editor’s note, a tight possibility of surviving the budget bill vote], that of negotiating a confidence vote agreement with the PS over 10 billion [euros less of cuts]. But Bayrou has gone over all our heads to save his image, even if not saving his skin.”

The general mood in the Macron camp was not one of pondering whether the prime minister will survive or be sent packing, which appears a given, but rather to imagine the possible scenarios post-Bayrou. However, few have a clear idea, less even than when Bayrou’s predecessor, Michel Barnier, similarly faced – and lost – a no confidence vote in December last year. That was also related to a budgetary bill, which Barnier forced through by decree. “Frankly, I don’t see any way out, it’s going to be hell,” said the Renaissance party MP cited immediately above. “Bayrou has thrown us under the bus, and now the pressure is upon the president.”

Among the possible options he sees is that Macron swiftly appoints a new prime minister in order to keep to the agenda of presenting the draft budget legislation. One of the names of potential replacements already circulating is that of armed forces minister Sébastien Lecornu. He would better suit the far-right, but would not please everyone in the centre-right parliamentary coalition. “I don’t see how Lecornu could reach a majority,” said Ludovic Mendes. “A section of those among us could not accept that he be appointed prime minister.”

Whoever Bayrou’s successor might be, Macronist or semi-Macronist, if they are expected to lead a policy that is broadly identical to his they will surely end up, and more rapidly still, dismissed by a no-confidence vote.

The Left obliged to make it up

Another option for Macron would be to again dissolve parliament, prompting new legislative elections, even though he firmly excluded the possibility in an interview with weekly news magazine Paris Match this month. But that was before Bayrou’s bombshell announcement on Monday. If snap parliamentary elections were called, they could be catastrophic for the leftwing NFP coalition, engaged in infighting throughout the summer, and which would find difficulty this time around in organising a list of common candidates from the four parties it represents. “That’s why we must today prepare for September 9th and not wait for the evening of September 8th,” said MP Pouria Amirshahi, whose Green party, Les Écologistes, is part of the NFP. “We would be mad to let ourselves be pushed at the last minute to the corner of a table.”

He said he believed if the broad Left, ranging from the radical-left La France insoumise (LFI) party to the PS, and including the Parti Communiste and Greens, fail to rally together, “Macron can succeed with the gamble he lost in 2024” – a reference to the snap legislative elections that year which led to the enduring parliamentary chaos. Macron’s “gamble” was that a divided Left would collapse, to the benefit of his own party which would become the only alternative to the far-right. That of course is to believe the so-called “republican front” – the term given to the rallying of the leftwing electorate behind any candidate fighting a far-right candidate – can still be mobilised.

It was thanks to the “republican front” that Macron was comfortably elected in 2017 and again in 2022 when he faced Marine Le Pen in the final, two-horse second rounds of both presidential elections. It was also how conservative Jacques Chirac was re-elected as president against Jean-Marie Le Pen, Marine Le Pen’s father, in 2002. But the deep sense of betrayal following Macron’s two elections, after which he gave little or no acknowledgement in form of policy concessions to the Left, leave a major question mark over it ever happening again today, or at least with any significant result.

The PS and LFI remain vague about any electoral alliance strategy. The issue was to be debated by the socialists at a meeting of their national bureau on Tuesday evening, and one internal source said that, at the very least, an agreement is envisaged for an alliance with the Greens and the communists. Jean-Luc Mélenchon’s radical-left LFI party, which continues to believe that the deepening political chaos would lead in the end to Macron’s resignation and presidential elections in January, has surprisingly not ruled out an alliance with the PS, with which it shares tense relations, in the case of snap parliamentary elections.

In an interview with Mediapart published on Tuesday, LFI parliamentary group leader Mathilde Panot left the door open for possible common candidates with the PS (i.e. one candidate representing both parties in a given constituency, so as not to dilute the vote), but said these would be handpicked. “We won’t have an alliance with those who have today rendered the Parti Socialiste detestable, meaning, for example, [former French socialist president, now again an MP] François Hollande,” she said.

“On the Left, our votes in [the lower house, the National] Assembly converge for ninety percent of legislative texts […] So we must show that we’re ready to govern” said Pouria Amirshahi.

Socialist MP Philippe Brun, however, is hardly optimistic. “If we return to the polling booths, the RN will win,” he warned. “Emmanuel Macron cannot dissolve [parliament] before testing the Left in power, and we are 100 votes short for putting a budget in place. We therefore have to seek an agreement with centrists to avoid a no-confidence vote for the [hypothetical] next budget.”

The French president dithered for weeks on end before finally appointing Michel Barnier as his first prime minister following the snap parliamentary elections that created the current hung parliament. But now, between the probable overthrow of Bayrou on September 8th, the day of strikes and protest marches against the budget proposals on September 10th, and the need to gain parliamentary approval for a 2026 budget by December 31st, Macron will have to swiftly announce his intentions.

-------------------------

- The original French version of this report can be found here.

English version by Graham Tearse