In 1952, Ginette Bac had been married to Claude Bac for four years. They lived in a cramped apartment in Saint-Ouen, a working-class, industrial suburb just north of Paris, and already had by then three young children. Ginette, who had, since her birth, suffered from a paralysis of her right arm, was becoming submerged by the domestic tasks of preparing meals, cleaning the home, and washing nappies and clothes by hand.

Then Ginette, who like Claude turned 23 that year, discovered she was pregnant with their fourth child. Despite logistical help from her mother-in-law, Léonie, Ginette found herself increasingly unable to cope. When Danielle, a girl, was born that summer, Ginette fell into what would today be diagnosed as postnatal depression, while Claude, who worked for a building firm, took on more and more overtime and was ever less present at home.

In January 1953, Ginette was devastated to find she was pregnant with a fifth child. Her mental health rapidly collapsed further; living behind closed shutters, she hardly fed or washed her children. In their admirably researched 2019 book (footnote 1) about the story of the couple and its aftermath, Tristes Grossesses (“Unhappy Pregnancies”), French historians Danièle Voldman and Annette Wieviorka write that the Bac’s apartment was “transformed little by little into a squalid hovel”.

Alerted by Léonie, who had become less present following a dispute with the couple, a social worker and a police assistant would occasionally visit the apartment. Then, in February 1953, eight-month-old Danielle died from malnutrition and lack of care.

A judicial investigation was opened, and Ginette and Claude Bac were placed in preventive detention. In what was a rare occurrence for the time, the magistrate in charge of the investigation had harsh words for the husband. “You do not appear to have considered, in making Ginette the mother of such a large family, the psychological and moral task that you imposed upon a young woman of 22-years-old,” the magistrate told Claude, as recorded in the papers of the case file. “Your moral responsibility begins there.”

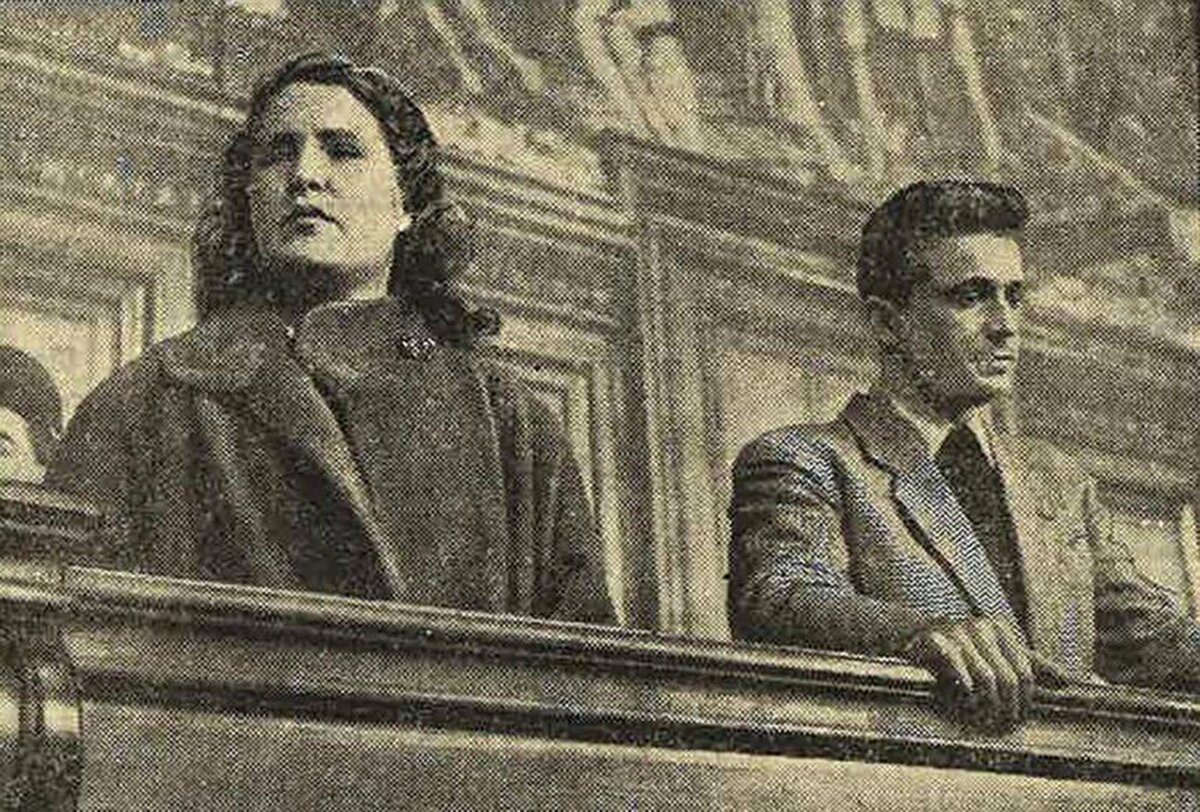

In those files, the magistrate also underlined the affection that Ginette, now freed of her endless domestic duties, showed towards her fifth baby, born while she was in detention. When the couple finally stood trial, in June 1954, the civilian jury, made up of seven men, found them “guilty, with mitigating circumstances”, no doubt in part due to the speech of Ginette’s female defence lawyer who had underlined her difficulties of handicap, the suffering brought about by the closeness of her pregnancies, and the financially precarious situation of the couple.

Enlargement : Illustration 1

The pair were each sentenced to seven years in prison, while Claude was deprived of what was then called in French law “paternal power”, a notion whereby the father was the head of the family (now known as “parental authority”, exercised equally by the mother and father). Their children were made wards of court. The trial was reported in the media as a story of passing interest, at the same level as that of dramatic accidents, bank robberies and murders. But when, one year later, the couple were sent for a retrial, it was to play an essential role in the emergence of the fight in France for access to contraception.

At the time when Ginette Bac had five pregnancies in the space of five years, abortion and the promotion of contraception and the sale of contraceptives were still strictly prohibited in mainland France, as set out by a law promulgated on July 31st 1920. In France’s overseas territories, however, such as the Caribbean islands of Guadeloupe and Martinique, and the Indian Ocean island of La Réunion, the French state led policies to limit the birth rate, including not only the dissemination of information about contraceptive methods, but even the practice of forced abortions and sterilisations.

In mainland France, where the outlawing of abortion was rooted in the 1791 criminal code, the 1920 law prohibited what was termed “anti-conceptional propaganda” – a crime which carried a jail sentence of several months. The legislation followed political concern over the strong decline of population numbers due to the First World War, which caused the deaths of more than 1.5 million French people.

But in the 1950s, despite the continued legal repression (2), women were having abortions. In the absence of contraception, it was “a sociological phenomenon, a habit contracted by all layers of society, a sort of necessary wrong”, wrote the late French investigative journalist Jacques Derogy in a first-ever study on the subject, first published in a series of articles in 1955 and then in book form in 1956 under the title Des enfants malgré nous : le drame intime des couples (published by Les Éditions de minuit).

According to some estimations, there were then around 800,000 abortions carried out per year, which was almost equivalent to the annual number of births. Most clandestine abortions at the time would have been carried out either alone or with the help of a friend, a sister or a neighbour. Beyond the use of catheters, the omnipresence of domestic objects, as well as their variety, is startling. Detailing them from his lengthy research, Derogy wrote of an “astounding bric-à-brac of hair pins, knitting needles, tooth picks, penholders, umbrella ribs, […], roots, chicken bones, […] injections of soapy water, tincture of iodine, spirits of salt, rye ergot fungus extract, […] ether, alcohol or glycerine, […], curling tongs, compasses, […] pieces of sealing wax!”.

Women suffered, stuck in a vice between the law and their refusal to have a child. When they had to go to the hospital in an emergency after a blundered private abortion, they sometimes faced a sort of disguised vengeance of society, for example doctors who carried out a curettage without anaesthetics. Tens of thousands of women died from makeshift abortions, and thousands of others became sterile. To all evidence, in previous times like those of today, the outlawing of abortion does not stop the practice but instead makes it fatal (as underlined on the placards of those currently mobilised around the world against the moves to remove or restrict the right to terminate pregnancy).

Paving the way for the family planning movement

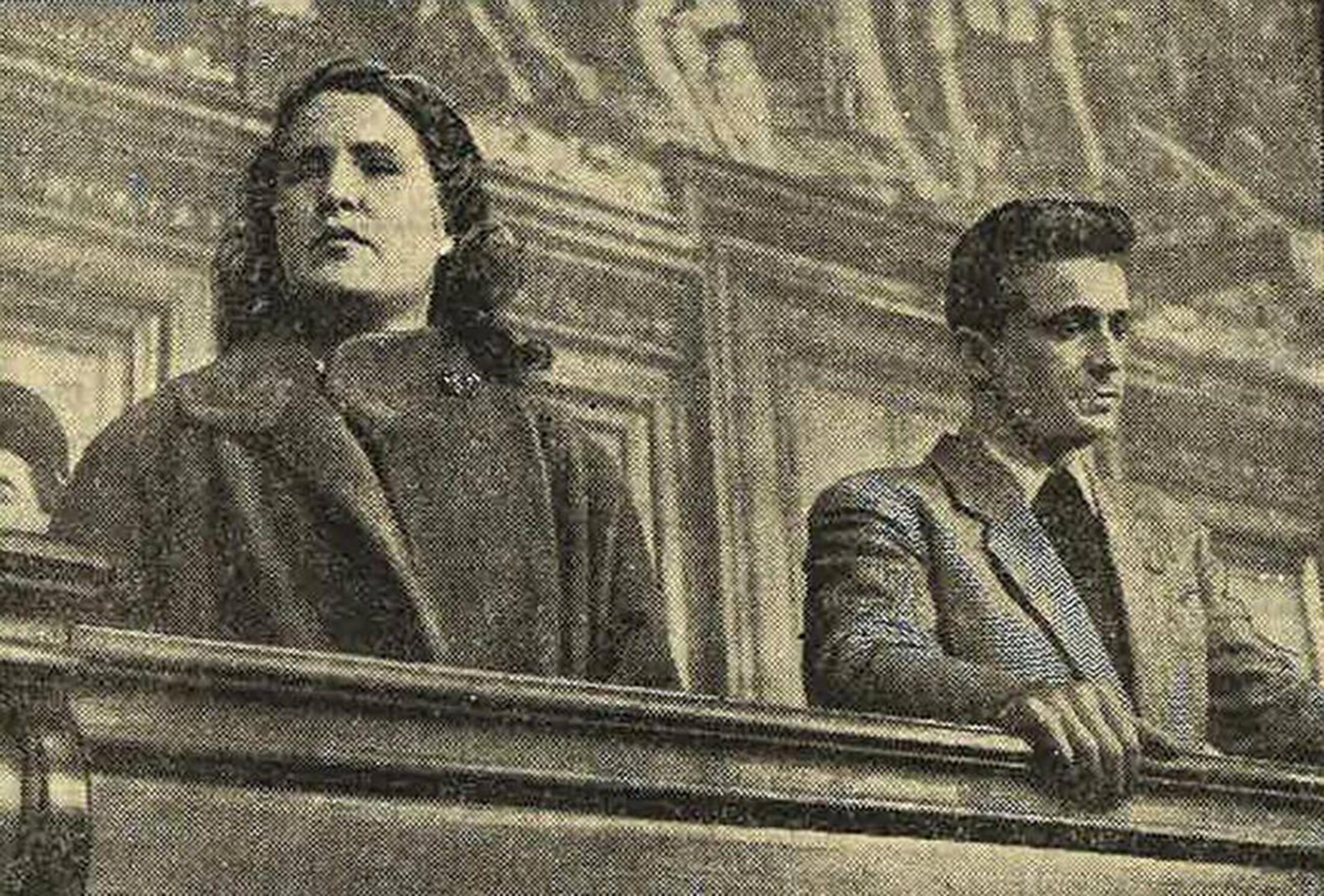

It was in that context that emerged in France a movement in favour of contraception as a sort of ‘remedy’ for abortion, championed by gynaecologist Marie-Andrée Lagroua Weill-Hallé (1916-1994). A leftwing Catholic, her future commitment was sparked in the late 1930s when, during a placement in a hospital surgery unit, she witnessed the mistreatment by young doctors of women who had aborted. During a trip to New York in 1947, she met birth control activists, including Margaret Sanger, the feminist and founder, in 1921, of the American Birth Control League. Lagroua Weill-Hallé visited the league’s clinics. These provided couples with the means to limit the number of births according, as Sanger set out, to their economic, physical and moral capacities. The onus was on the happy family, rather than the large family.

Enlargement : Illustration 2

In March 1953, Lagroua Weill-Hallé published an article in a medical review, La Semaine des hôpitaux, in which she called for a reform of the 1920 law supressing contraception. But it received little reaction. As Danièle Voldman and Annette Wieviorka recount in their book Tristes Grossesses, for Lagroua Weill-Hallé to attract support for her argument, “there had to be a tragic story capable of moving opinion and to make it accessible [to understanding] what was at stake in birth control. It would be the Bac affair.”

The result of the first trial of Ginette and Claude Bac in 1954 was overturned on a technicality, and they were sent for retrial in Versailles in the summer of 1955. Lagroua Weill-Hallé was called as a witness for the defence to explain the wider questions that lay behind the tragedy. Her account impressed the court, as well as the numerous journalists attending the hearings, and the focus of the new trial shifted from that of the couple alone into a larger societal issue, bringing the 1920 law into question.

On July 7th 1955, the jury, composed of five men and one woman, pronounced a more lenient verdict than that of the first trial. Ginette and Claude Bac were found “guilty of having […] by clumsiness, carelessness, inattention and negligence, been involuntarily the cause of the death of their daughter Danielle”, and were sentenced to two years in prison, which they had already served in preventive detention.

The couple walked free from the court and were soon forgotten by the media. But their case paved the way for the creation of one of the largest feminist associations of post-war France, namely the Planning familial.

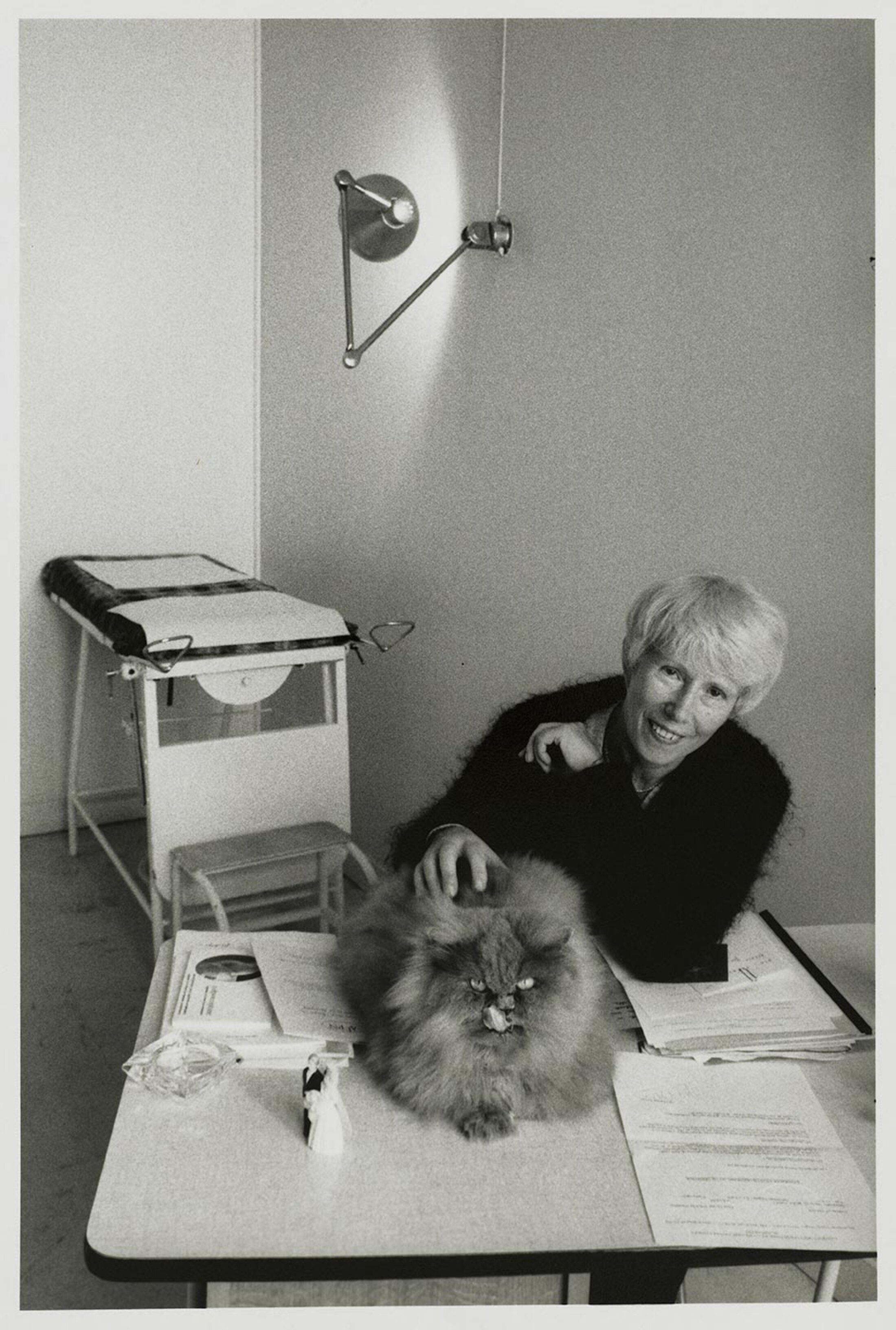

For it was a few months after the Versailles court verdict when Lagroua Weill-Hallé was contacted by Évelyne Sullerot (1924-2017), then a house-bound mother of four, who wrote to her to propose the creation of a women’s association for the controlled self-planning of pregnancies. “Who would have the courage to set in motion the chorus of women who have since thousands of years whispered in private?” wrote Sullerot. She received an enthusiastic response from Lagroua Weill-Hallé, and the project was launched.

To avoid problems from the authorities with regard to the 1920 law prohibiting the promotion of contraception, they chose a name that would arouse no suspicion: La Maternité heureuse (Happy Maternity). Joined in the adventure by Lagroua Weill-Hallé’s husband, Benjamin Weill-Hallé, an eminent paediatrician and bacteriologist who had a vast network of contacts, the two women convinced numerous women intellectuals, lawyers, doctors, and also the wives of influential men, to support their project.

Most of these women were the mothers of several children, a fact that would be at the heart of their strategy for ensuring their cause was not interpreted as being anti-family. On the cover of Lagroua Weill-Hallé’s 1959 book Le Planning familial (published by Librairie Maloine) was a photo of four happy-looking little children, one with a necklace bearing a Christian cross – clearly intended to win over Catholics.

Enlargement : Illustration 3

Évelyne Sullerot later wrote how, when registering the statutes of the association La Maternité heureuse at the administrative offices of the prefecture, she did so sitting with her baby on her knees, prompting an approving comment from the female registrar. “The Happy Maternity? Ah, I see!”, she recalled the woman as saying. “She never suspected that we were going to change society.”

Vigorously opposed by the French Communist Party

Pioneers in France, where no resources for their project existed, Sullerot, Lagroua Weill-Hallé and their colleagues approached similar organisations in those countries where contraception was fully authorised, such as the United States, Britain, Sweden and Belgium. French historian Bibia Pavard, specialised in research into the struggles for the right to contraception and abortion, described what she called a “militant transfer” in the meetings of the International Planned Parenthood Federation (IPPF), which La Maternité heureuse became a member of in 1959. French doctors and nurses were sent for training in methods of contraception, visiting clinics and acquiring, among other things, pills and diaphragms.

In France, the Maternité heureuse militants faced hostile opposition to their cause, and adapted their language accordingly. Instead of talking of “planification familiale” or “contrôle des naissances”, which might have sounded like policies imposed by the state, or even recall for some Nazi eugenics, Lagroua Weill-Hallé coined the term “planning familial” (family planning) in France, which she defined as “all the measures aimed at favouring births when the social, material and moral conditions allow”. By using the notion of “planning familial”, argues Bibia Pavard, she created “an instrument of a vigorous natality in order to win over the natalists” opposed to her cause.

Meanwhile, La Maternité heureuse also faced another major opponent in the form of the then-powerful French Communist Party (PCF). While some of those close to the party supported the family planning campaign, like Jacques Derogy, its leaders considered the cause to be that of a bourgeoisie, neo-Malthusian, and imported from the United States. In an open letter published in the communist daily L'Humanité on May 2nd 1956, PCF general secretary Maurice Thorez addressed Derogy, who had recently published his book Des enfants malgré nous, detailing his lengthy investigation into the horrors of clandestine abortions, and how they might be prevented. Advising Derogy to read Lenin’s view of neo-Malthusianism instead of “inspiring yourself with the ideologies of the large and small bourgeoisie”, Thorez declared that “the path of the liberation of women is through social reforms, through social revolution, and not abortion clinics”.

Derogy later recalled how, shortly after that, Thorez’s wife, Jeannette Vermeersch, a leading figure of the party and who was vice-president of the French Women’s Union (UFF), also addressed him: “Since when would working women [supposedly] have claimed the right to attain the vices of the bourgeoisie?” she asked. “Never!”

Such arguments, which ran counter to the reality of society, caused distress and anger among the family planning militants and among doctors who were PCF sympathisers. In their book, historians Danièle Voldman and Annette Wieviorka estimated that the alliance against the militants created between the PCF and Catholic members of the parliamentary lower house, the National Assembly, delayed by “around 12 years” the possibility for French women “to freely access contraceptive means”, surely resulting in yet further deaths and suffering.

From early activism to the legalisation of the contraceptive pill

It was in 1960 that the association Maternité heureuse became renamed as Le Mouvement français pour le planning familial (The French Movement for Family Planning), or MFPF, and began operating on a much larger scale, opening centres around France. In her 2012 book Si je veux, quand je veux (3), Bibia Pavard writes that, while continuing its “lobbying for legislative change”, the movement now sought to disseminate information to the greatest number possible about contraceptive practices and sexuality, in the hope that the 1920 law “would end up falling by itself into abeyance”.

The MFPF opened its first centre in the city of Grenoble, in east-southern France, in 1961, followed months later by another in Paris. These were places where the 1920 law was stepped around by allowing access only to members of the association, and by acting to the letter of the law which did not precisely prohibit the use of contraceptives (which doctors would purchase in Britain) but rather their sale and “anti-conceptional propaganda”.

Through the initial support of trades unions and local groups including freemasons, Socialist Party branches and secular associations, the Family Planning movement grew in its sociological spread, notably attracting members among the teaching profession. It was also soon a time of the first internal conflicts between the movement’s ‘experts’ and newly arrived ‘militants’ who wanted to politicize its actions. Lagroua Weill-Hallé criticised the latter for what she called their “crusade for secularity”.

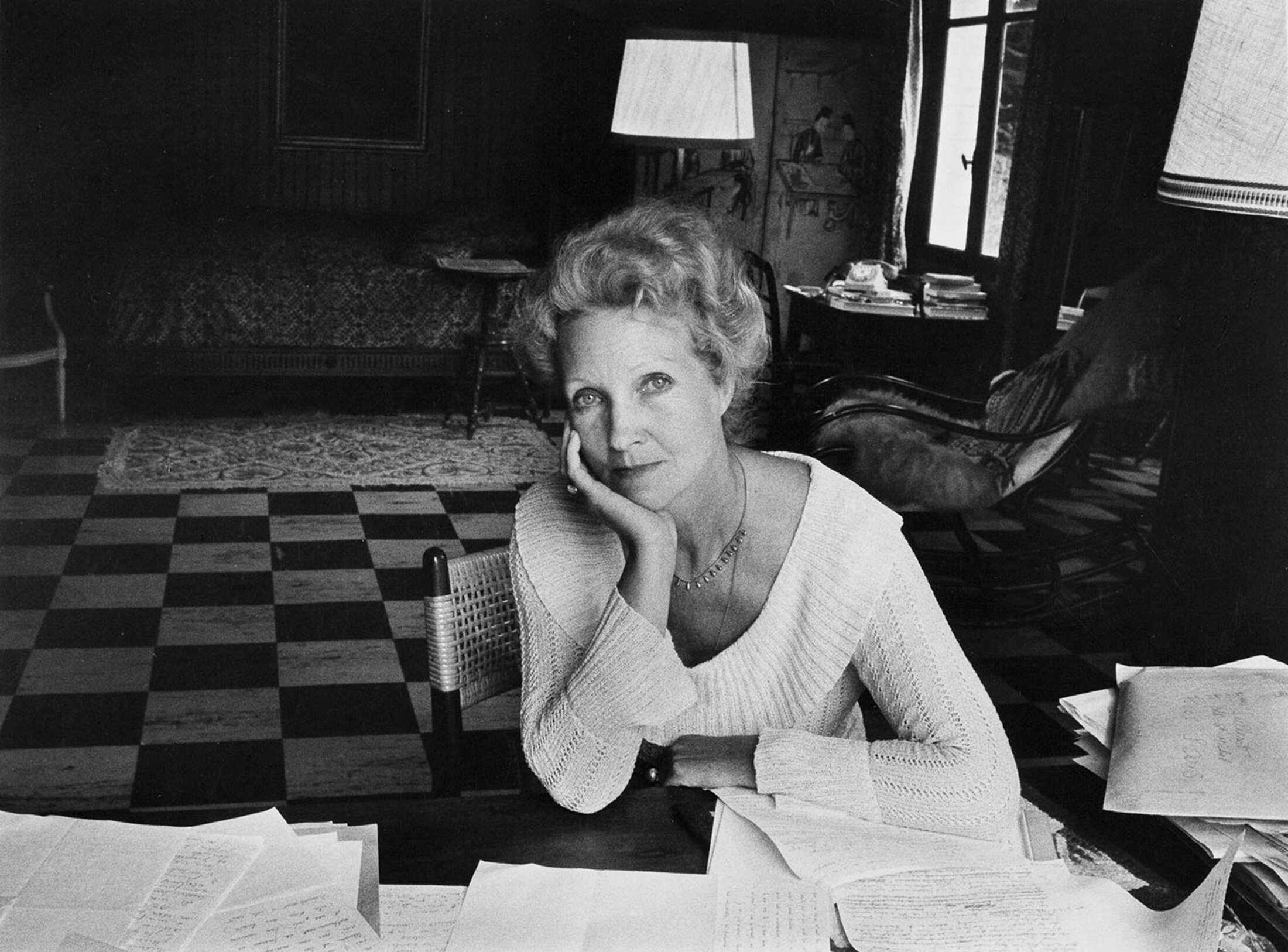

Enlargement : Illustration 4

In 1965, notably with the candidature of the socialist and pro-contraception François Mitterrand for that year’s presidential elections, contraception became an issue in national political debate. But it was an issue monopolized by men in dominating positions who were members of the circles where the outlines for a new legal framework were discussed. At the time, there were just eight women members of the National Assembly. “The ‘dining-room politics’ of the Maternité heureuse were substituted by muffled ‘salon politics’, where one smoked a cigar between men,” writes Bibia Pavard in her book Si je veux, quand je veux.

It was finally a Gaullist conservative Member of Parliament, Lucien Neuwirth, who proposed draft legislation to legalise the sale of contraceptives, and notably the contraceptive pill. What became known as the “Neuwirth law” was adopted by Parliament in December 1967, after lengthy debates and amendments which reduced its initial ambitions; written parental consent was required for access to the pill or a coil by a woman under the age of majority, which was then 21 (it became 18 in 1974). The price of contraceptives was not reimbursed by the state, and the publicity and promotion of contraception remained prohibited.

Marie-Andrée Lagroua Weill-Hallé left the Family Planning movement before the law was adopted, in part because she considered that her initial objectives had been reached, with the population largely in support of her cause. But her move was also over her disagreement with the politicization of the movement, which she would rather have preferred to become transformed into a sort of public service for contraception.

For feminist militants, whose influence was increasing and causing tensions within the Family Planning movement, the combat had only just begun. For them, the fight was now on for minors to have free access to contraception, for the refunding of the cost of contraceptives by the state healthcare system, and the introduction of sex education classes. Not least was the new battle for the right to abortion.

‘Big challenges remain’

Between the 1960s and today, the French Family Planning movement has undergone numerous changes, but its founding combat has remained at the heart of its actions. While the issue of contraception no longer makes headlines, not all of its original demands have been put in place, and there are still women like Ginette Bac who do not have the possibility of choosing when they become pregnant.

“The refunding of the contraceptive pill for the under-26s, the emergency pill free-of-charge for all – at a level of rights, there are advances,” commented Claire Ricciardi, who has been a member of staff of the French Movement for Family Planning for 20 years, and who is now co-president of the branch for the Bouches-du-Rhône département (county) in southern France. “But there remain big challenges, beginning with access for all to correct, and complete, information.”

“We still have [high-street] pharmacists who tell the young that the ‘morning after’ pill can cause cancer or cause sterility if one takes it several times, its astounding,” she said.

But there is also a lack of resources for effective prevention campaigns in secondary schools, where sex education courses remain rare, despite the requirement, under a 2001 law, for each school to organise three per year. “In interventions at schools, the accent, as a priority, is put on girl-boy relationships, sexist and sexual violence, the different sexual orientations, and in the end there is no time for talking about contraception,” added Ricciardi. “That’s how we find ourselves with youngsters who think that the pill protects against sexually transmitted diseases.”

-------------------------

1. Tristes Grossesses : l’affaire des époux Bac (1953-1956), by Danièle Voldman and Annette Wieviorka, is published in France by Seuil (2019).

2. In 1943, under the collaborationist Vichy regime during the German occupation of France, Marie-Louise Giraud, a woman of no medical training, and a doctor, Désiré Pioge, were both sent to the guillotine for having practiced abortions. While the 1940-44 Vichy regime was particularly repressive, with an average yearly 3,800 convictions for abortion handed down, there were still hundreds of others pronounced during the 1950s.

3. Si je veux, quand je veux : contraception et avortement dans la société française (1956-1979), by Bibia Pavard, is published by Les Presses universitaires de Rennes (2012).

-------------------------

- The original French version of this article can be found here.

English version by Graham Tearse