The scandal over alleged child abuse at the private Catholic school Notre-Dame-de-Bétharram near Pau in south-west France stretches back three decades but is now causing more shockwaves than ever. The case – known as the Carricart affair after Father Pierre Silviet-Carricart, a director at the prestigious school who was accused of raping a ten-year-old pupil – has also taken on a political dimension. Prime minister François Bayrou, who was a Member of Parliament for the area and whose political stronghold is in that region, has publicly denied that he had ever been made aware of the abuse allegations, despite evidence to the contrary reported by Mediapart.

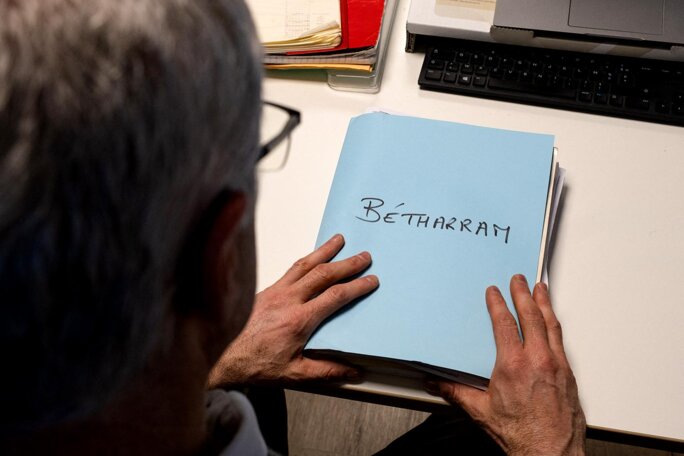

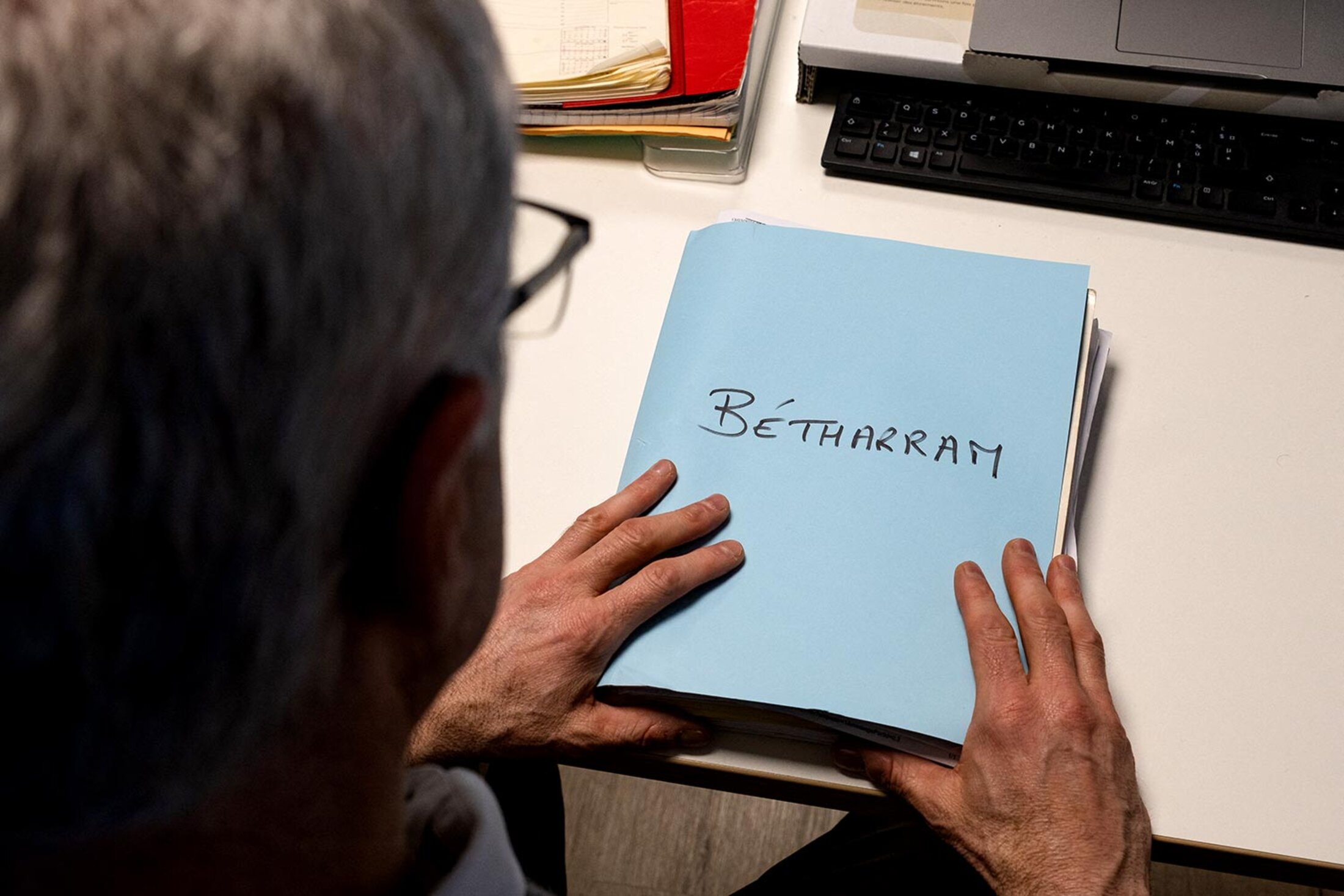

Gendarme Alain Hontangs, now retired, was the senior detective in charge of the investigations into the Carricart case at the end of the 1990s. Quickly released before being moved to Rome, the priest took his own life in 2000 before he could stand trial. Alain Hontangs says he wants full clarity surrounding this episode.

Speaking on the TF1 programme 'Sept à huit' on February 16th, the former gendarme described how he had been told that François Bayrou had intervened with the public prosecutor at the time of the criminal investigation - something the prime minister denies. Back then Bayrou was president of the Pyrénées-Atlantiques département or county council, having recently left his role as minister of education. Several of his children were pupils at Notre-Dame-de-Bétharram, where his wife, Élisabeth Bayrou, also taught. She later attended Father Carricart’s funeral in 2000.

In this interview with Mediapart, Alain Hontangs stands by his claims and backs calls for an administrative inquiry into how the case was handled, stressing the significance of the issue given the number of allegations that have since emerged.

Mediapart: On TF1, you described a surprising incident at the start of the investigation into Father Carricart in 1998. After you had questioned the priest following a complaint of sexual assault from a former underage pupil, his appearance before the investigating judge was reportedly delayed. You said the judge told you that François Bayrou had “intervened with the attorney general, who wanted to review the case file”. Can you confirm this?

Alain Hontangs: Yes, that is what I was told at the time. You can ask any detective in France - few will tell you that, during the appearance [in front of a judge] of a person in police custody, the chief prosecutor suddenly requests to see the file. I remember it clearly. I had the case file myself. And I was taking it to the Pau high court at the same time as I was escorting Carricart.

Enlargement : Illustration 1

As for the reasons that might have led Mr Bayrou to intervene, perhaps he acted as a parent of pupils. If my children had been at that school, I would have asked myself some questions too. Mr Bayrou knows full well that an investigating judge handling the case is not going to respond to him. So he has to find another person to talk to.

Mediapart: As it turns out, we now know that François Bayrou did personally meet the investigating judge Christian Mirande during the inquiry.

A.H.: I don't know that.

Mediapart: It's now been confirmed by both parties. Christian Mirande has never wavered on this point, while François Bayrou eventually admitted it after initially denying it. Does the fact this meeting took place surprise you?

A.H.: That Mr Mirande spoke to him - yes, that does perhaps surprise me. [Pauses.] You can even remove the “perhaps” from that sentence.

Mediapart: When asked about your statements regarding the possible intervention with the chief prosecutor - something he allegedly mentioned to you - Judge Mirande told us he had no memory of it, while still describing your testimony as “perfectly credible”. Conversely, François Bayrou has strongly objected to your account, arguing that “one would have to know nothing about how the justice system works to imagine a chief prosecutor intervening in such a manner”. How do you respond to that?

A.H.: He's responsible for his own words. I make no comment on them. And if I do have comments to make, I'll save them for the administrative inquiry.

Mediapart: A lawyer who has represented victims from Notre-Dame-de-Bétharram, Jean-François Blanco, has now formally called for an inquiry to be opened. Do you support that?

A.H.: I hope there is one, because I think it's important to look into how this case was handled, so that everything is made clear. There are people who could 100% confirm what I'm saying.

Mediapart: Who?

A.H.: I'll reserve my explanations for the inquiry.

Mediapart: Since your testimony on February 16th, have you been contacted by the judicial authorities or even by the gendarmerie?

A.H.: No, but these things take time to get going.

Mediapart: A key moment in the Carricart case was his release - just two weeks after being placed under investigation and remanded in custody - in a decision by the Pau Court of Appeal on June 9th 1998, following supportive submissions from the prosecution. What was your reaction at the time?

A.H.: At the time, we thought it was a bit much, but we accepted it as just one of those things. After 20 years in the investigative branch, you learn to grow a thick skin. Today, together with what I've since read, I'd say my reaction is more one of anger. Releasing him was an irregularity.

I make a comparison with another case I handled some time earlier, also involving Mr Mirande. It concerned a father accused of incest by his daughter, who was placed in pre-trial detention. He spent more than three months in custody while I carried out investigations under [delegated powers] from Mr Mirande. In the end, I proved that the locations she described as the scene of the rape, which allegedly took place years before, did not exist.

There were also phonetaps which led to a recognition that she wanted to take revenge on her father. But in the meantime, he had spent three months in custody while the investigation took place. This farmer had not been defended by Mr Legrand [editor's note, a leading lawyer in Pau, who represented Bétharram and Father Carricart]. “Depending on your power or lack/ Judgement will paint you white or black”. [Editor's note, he is quoting here from a famous fable by 17th century poet Jean de la Fontaine about the inequalities of justice.]

Mediapart: Local newspaper archives from the time suggest that one of the reasons given for Mr Carricart’s release from custody was that the alleged offences dated from the 1980s and that he had “spontaneously” presented himself to the investigating judge, supposedly reducing the risk of flight...

A.H.: Yes, he came forward with divine blessing [laughs]. No, no, it was all carefully worded to suggest he was acting in good faith and had voluntarily gone to the investigators, but he did not know why he had been summonsed. When the time came to question Father Carricart, there were several options. The first was for Mr Mirande to issue a formal legal request to Rome [editor's note, where Carricart was living at the time]. The second was to persuade him to return to France. We chose the latter.

Enlargement : Illustration 2

I assigned a detective from the investigation unit, who spoke Souletin Basque [editor's note, a dialect of the Basque language], to call Carricart, who was also a Souletin Basque, and explain that it would be good for us to hear from him in his capacity as director of Bétharram as part of an investigation. I instructed this detective to write up a formal account of what was said. Carricart returned to France, and I went to collect him from Bétharram, where he was staying - that’s how it happened. It was far from being some form of divine intervention in which Father Carricart knocked on the door of the investigation unit asking: “What do you want from me?”

Mediapart: In January 2000, the cleric took his own life in Rome after being summoned in connection with a second complaint against him. 'Antoine' - not his real name - spoke about it to Mediapart. Do you remember him?

A.H.: Yes, he was one of the victims I had interviewed under [delegated powers from the investigating judge]. A boarder at the time, he initially told me: “No, no, nothing ever happened to me.” And then, over time, things changed. A year and a half later, he came forward to Mr Mirande.

If he had remained in Pau prison, the investigation could have continued, and he would have stood trial. [...] Perhaps the victims who are speaking out today would have spoken much sooner.

Mr Mirande had asked me to contact boarders who had been there at the same time as 'Franck' [editor's note, the initial complainant; this is not his real name]. The scope of the investigation was limited - we did not look before or after that period. But within that time frame, there was already one victim, and Franck himself had mentioned the possibility of other victims and other perpetrators.

Mediapart: And other potentially criminal acts that you could have investigated at the time?

A.H.: Yes, but when you're working under [delegated powers from the investigating judge], you're bound by the initial indictment [editor's note, a document issued by the prosecution that defines the scope of the investigation]. That indictment covered only the acts committed by Carricart against Franck. That said, I had indeed seen evidence concerning [editor's note, he mentions the name of a supervisor now under investigation in ongoing judicial proceedings], but I could not question him as I was prevented by the [delegated powers].

Mediapart: In the end, the investigation ended with Father Carricart’s death in Rome. What conclusions do you draw, given the number of complaints today alleging systemic abuse at the institution?

A.H.: One can speculate about what might have happened. Father Carricart was released under judicial supervision just after being remanded in custody by Mr Mirande. If he had remained in Pau prison, the investigation could have continued, and he would have stood trial. Whether he would have been convicted or acquitted at trial is another matter, but at least the victims would have felt supported. And perhaps those who are speaking out today would have felt included or would have spoken much earlier.

Put yourself in the shoes of a victim reading in the newspaper that the perpetrator of a rape has been released under judicial supervision just ten days [editor's note, in fact thirteen days] after being remanded in custody. Victims will wonder: “Will I be believed or not?” From what I read today, this is what many are saying. They tell themselves: “My family doesn't believe me, and the justice system will never believe me.” These victims didn't come forward at the time and, as a result, we've lost twenty years.

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

- The original French version of this interview can be found here.

English version by Michael Streeter