A tangle of sheet metal embedded in a concrete wall, a shattered windscreen. A scooter that has split into pieces in a sea of oil and blood, fire crews running with a stretcher. We all know what a road accident looks like.

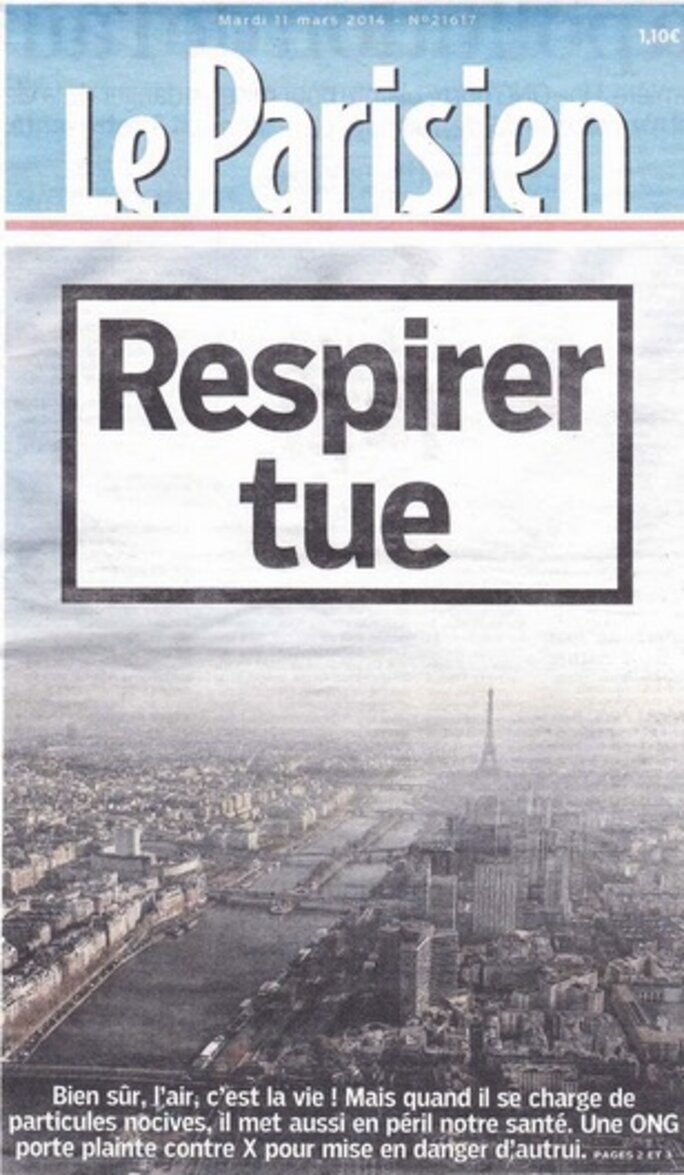

But what about dying from air pollution? What are the visible signs of that? We never see crowds of pedestrians collapsing when the Paris sky turns grey from nitrogen dioxide, nor bodies piling up by the sides of gridlocked streets. We do not see the deaths caused by pollution. The tiny particles kill those who breathe them, but no one sees them.

Yet in Paris alone the number of deaths caused by air pollution can be numbered in the thousands. A recent figure suggests that 2,500 people a year die in the French capital because of the air they breathe. This little-known figure can be found in an annex to a report by the public health body Santé Publique France published in June this year. You have to wade through to page 116 of the thick document to find it. It is a disturbing figure because it is difficult to understand. It is not the result of a body count but stems from a statistical estimate. The mayor of Paris, Anne Hidalgo, has even suggested that as many as 6,500 people in the greater Paris region die each year as a result of polluted air.

“You don't die from the pollution, you die from the illnesses that stem from it,” explains Bernard Jomier, a doctor who is in charge of health issues at City Hall in Paris. “You can publish the photo of someone who's died from diabetes but not that of a pollution victim.” To measure the number of lives cut short by dirty air in Paris, researchers had to extrapolate from French and European epidemiological studies linking atmospheric pollution to local residents' state of health. In concrete terms, it means measuring the additional risk caused by air pollution. “This work is the culmination of quite a process,” explains Sabine Host of the Paris regional health observatory the Observatoire Régional de Santé d’Ile-de-France. There is, then, some uncertainty over the nature of the figures.

Enlargement : Illustration 1

And that uncertainty is precisely the problem. It will never be possible to give air pollution as the cause of someone's death. “It's not a specific illness, but an additional risk factor,” says Sabine Host. Nonetheless six or seven people die as a result of it each day in Paris. “You can't escape pollution,” Host points out. For while one can chose whether to smoke or not, you cannot chose which air you breathe. “One should take these figures with a lot of caution,” says Bernard Jomier from City hall. “History shows that the impact of pollutants on health is always underestimated. We had the same thing with lead poisoning, which was denied by City Hall in Paris in the 1990s.” A study by Santé Publique France says that if Parisians were able to breathe air free from human-caused pollution they would gain more than two years in life expectancy.

This human toll sheds light on the controversy over the pedestrianisation of the Georges-Pompidou highway on the right bank of the River Seine in Paris. On Monday September 26th, city councillors voted to ban cars from this 3.3km stretch of urban motorway. Politicians on the Right, who voted against, are up in arms over the pedestrianisation project and see themselves as standing up for discontented motorists. The ruling majority of the Left backed the measure despite the unfavourable opinion of a commission of public inquiry. In this delicate political period, after the Right took power on the Paris regional council last December, and a few months before the presidential election campaign, the place of the car in Paris's life has become the object of bitter political disagreement. But amid the discord the crucial issue at the heart of the debate is often forgotten: that of the health of the inhabitants and their inequality in the face of pollution.

“Air pollution kills and causes illness,” states Bruno Housset, head of the respiratory department at the Créteil hospital in south-east Paris and vice-president of the respiratory foundation the Fondation du Souffle. “The types of impact on health are not peculiar to Paris.” For people who suffer from respiratory illnesses, exposure to polluted air can lead to cardiovascular problems and finish them off, he says. Jocelyne Just, head of the allergy service at the Trousseau hospital in Paris notes: “Pollution exacerbates the condition for people who suffer from asthma or coronary heart disease, for people who have had strokes.”

'More than the number of lung cancer deaths'

Air pollution is a complex cocktail, made up of primary pollutants directly emitted by road traffic, industry, heating and farming, plus substances produced by chemical reactions in the atmosphere, such as nitrogen dioxide. By studying minute particles 2.5 micrometres in diameter - particulate matter 2.5 or PM2.5 - the pollution indicator most monitored for its effects on health, researchers at Santé Publique France have estimated that they are responsible for the deaths of 48,000 people a year in France. That is 9% of the national mortality rate. “It's more than the number of deaths from lung cancer, which kills around 30,000 people a year,” says Bruno Housset. Some 78,000 deaths a year are attributed to tobacco use.

The people who die are hit by the harmful effects of pollution peaks but are also affected by background pollution, in other words the permanently dirty air that they breathe. And the bigger the urban areas, the higher the concentration of PM2.5. According to the European Environment Agency more than 90% of city dwellers in Europe are exposed to pollution levels considered to be harmful for the health by the World Health Organisation. Scientists now consider air pollution to be the main environmental cause of premature death in the world.

Enlargement : Illustration 2

Who dies from air pollution? “It's difficult to say,” says Jocelyne Just. “You can say who suffers: it's vulnerable people. Newborns, infants, the elderly and people with chronic illnesses.” In Paris the risk of dying from pollution is low but it is a risk that affects everyone. The tiny particles, emitted in particular by diesel combustion, penetrate deep into the lungs and enter blood vessels. Once they are in the blood they have an inflammatory effect and stimulate platelets, a part of the blood that stops bleeding, and this creates coagulation problems. This situation can encourage clots to form and cause cardiovascular events, and can result in cognitive disorders. In some people this can aggravate diabetes, while exposure to air pollution can also stimulate pollen allergy. Lung development in infants is also impaired by air pollution.

“We find particle pollution in the macrophages [editor's note, a type of white blood cell] in the lungs of asthmatic infants,” says Jocelyne Just. A child can even be affected in the womb if its mother breathes in polluted air. In some pregnant women monitored with sensors, researchers have detected the appearance in the umbilical cord of genes linked to the development of asthma. And following delicate operations to wash the lungs of infants with severe asthma, allergy experts at Trousseau hospital have discovered “black particles” similar to those found in smokers' lungs. “It's quite worrying. What will that lead to? Probably chronic inflammations and the onset of illnesses,” says the doctor.

In a study published in July by the journal Epidemiology, researchers compared death rates in Tokyo, where the number of diesel vehicles has been drastically reduced, and Osaka, where there have been fewer restrictions and for a shorter period. The finding was that the rate of deaths in Tokyo resulting from pulmonary diseases was 22% lower than in Osaka, 11% lower from cardiovascular diseases and 10% lower for heart disease.

In 2015 researchers studied the effect of a reduction of air pollution in California on lung development in children. “We have shown that improved air quality in southern California is associated with statistically and clinically significant improvements in childhood lung-function growth,” said the authors of the study, published in The New England Journal of Medicine.

To give one concrete example: a patient of Bruno Housset from Créteil hospital declared that after returning to Paris following a holiday in the countryside he was no longer able to breathe as well. This type of statement is also not unusual among parents of children living in the Paris region, who sometimes observe a similar phenomenon in their children. “If there was no background pollution, which damages the respiratory function of the inhabitants, the [pollution] emission peaks would not have the same consequences.” says Bernard Jomier from City Hall.

More deaths among the disadvantaged

So breathing the Paris air kills. But it does not kill everyone and not in the same way. “The most vulnerable population groups economically have a higher risk of death,” says academic Séverine Deguen. In 2015 she and a group of fellow researchers published the first study on the links between air pollution and residential areas in the French capital. It turns out that economically disadvantaged people are more vulnerable to air pollution and potentially more sensitive to peaks in emissions, whose effects are multiplied by the chronic exposure of residents to nitrogen dioxide – the pollutant observed in this study.

Unlike in many American cities, working class areas in Paris are not necessarily more polluted than more affluent districts. If one looks at a map of the residential areas affected by the greatest concentrations of nitrogen dioxide particles, emitted in particular by diesel vehicles, they trace the line of the 'Périphérique' or ring road that goes around Paris, in the north as well as the south of the city. The great boulevards and the major Alésia crossroads in southern Paris, which are strongly exposed to pollution, pass through areas which are to a large extent well-heeled. However, many crèches, child care centres and nurseries are also situated close to the main ring road. According to a study from the Observatoire Régional de Santé d’Ile-de-France, proximity to major roads is responsible for around 16% of asthma cases among under 17s. In Paris and the surrounding region close to 30% of the population live less than 75 metres from a major axis road, defined as a route which is used by more than 100,000 vehicles a day.

However, it is their life circumstances that make disadvantaged households more vulnerable to pollutants. The researchers put this down to several explanations: a poor state of health due to a lack of aftercare (diabetes, obesity for example), lack of physical exercise, poor quality of housing, exposure to poor surroundings in the workplace and while travelling, and a low level of education which makes it harder for preventative health messages to have an impact.

Moreover, while better-off families can get away from Paris for the weekend or for holidays, poorer families are trapped in Paris and cannot escape from its polluted air. On top of the dirty air there is also noise pollution emanating from the major roads, a cause of stress and related illnesses. In 2013 in Lyon in eastern France researchers highlighted a possible link between exposure to noise and the mortality rate of infants born to disadvantaged families.

If it is clear that disadvantaged people are the most affected by air pollution, whose vehicles is it that put the most particulates and nitrogen dioxide into the Parisian air? A study of individual travel movements in the capital shows that car use is very low. On average just 10% of journeys are made by car. The exception is the capital's 16th arrondissement, where many very wealthy households live; here 19% of trips are made by car, nearly double the capital's average. However, this finding is not reflected in the travel patterns when they are analysed by job category. These figures show that 23% of journeys made by workers are in their car, against 12% for managers and executives. Jérémy Courel, a statistician at the urban development institute the Institut d'Aménagement et d'Urbanisme (IAU), says that the categories of workers who use their vehicles the most are artisans and tradespeople.

Ever since the 1990s research has been highlighting the impact of the French capital's polluted air on its inhabitants. The understanding of this phenomenon has gradually led the authorities to implement policies to reduce the role of vehicles there. Though the restrictions imposed on motorists are still a lot less than in many other large Western cities – for example Tokyo, Berlin and London – the reduction in road traffic has had a positive effect on the Parisian air. Between 2002 and 2012 emission levels of nitrogen dioxide and particulates fell by 30%. According to the association AIRPARIF, which is in charge of monitoring air quality in Paris, a third of this reduction stems from road improvements. It is an argument that backs up the case for pedestrianising the Georges-Pompidou way along the Seine; the fewer fast routes there are, the fewer cars there are and the cleaner the air is.

But the disappearance of the urban highway along the Seine will not resolve all of the problems, as recent history has shown. The growing use of diesel cars in Paris has offset some of the improvements in air quality, says AIRPARIF. Pollution emissions would have come down further if the number of diesel vehicles on the roads, especially those used for deliveries, had not grown. So, banning cars along the Seine will have only a limited effect; an inevitable confrontation with the automotive industry is yet to come.

-------------------------------------------------------------------------------

- The French version of this article can be found here.

English version by Michael Streeter