In recent months two separate films have been under preparation about the life of the iconic French fashion designer Yves Saint Laurent, who died in 2008. One of them, entitled Saint Laurent, is directed by Bertrand Bonello, the other, called Yves Saint Laurent, by Jalil Lespert. On the face of it, the rivalry between the two films should simply be one of artistic merit and box-office success.

But this is no ordinary big screen contest between two competing productions. For the saga has been complicated by the intriguing intervention of Pierre Bergé, a powerful figure who was Saint Laurent's long-term partner and co-founder of the Yves Saint Laurent fashion house, and who is today a prominent businessman who part owns France's best-known newspaper Le Monde. Bergé has been discreetly refereeing between the two rival productions from the sidelines, while strenuously trying to avoid looking like a censor, even though he has clearly taken sides.

The essential ingredients for understanding this drama within a drama were contained in an interview given by Bergé on the Le Petit Journal programme on cable and satellite broadcaster Canal+ on 21st June (see below). The TV appearance also highlighted the imprecise nature of Bergé's role in relation to the films, his method of doing things and, above all, the reason behind his preference for the Lespert film over Bonello's. The interview also revealed the paradoxes of this major personality, who is as well-known for his generous gifts and his commitment as for his rages, whims and his threats.

At one point in the interview the presenter Yann Barthès showed the businessman a photo of the actor Jérémie Rénier and asked: “You don't want this actor to play you in the cinema? Jérémie Rénier was going to be in the planned film on Saint Laurent by Bertrand Bonello...he's been blocked for the moment.” To which Bergé replied: “Not by me.”

Pierre Bergé apparently learnt via the press that Bertrand Bonello was planning a film on Yves Saint Laurent. He did not know Bonello personally but was assured that he was a talented director. The problem was, Bonello had started his project without going to see the businessman first. Moreover, Bergé had also learnt that another film on the same subject was being made, this one directed by Jalil Lespert. And Lespert did come to see him. That changed everything. “Yes, I am putting Yves Saint Laurent's clothes at [Lespert's] disposal so that it's the genuine clothes that will be paraded in the collections that he will obviously show,” Berge told Le Petit Journal. “If Monsieur Bonello had sought me out, perhaps my attitude would have been different.”

The question of Pierre Bergé's role in supporting or hindering a film that involves his life is an important one, and one with wider implications. It highlights the influence of certain networks at the heart of French cinema and also the interest that some powerful people take in their image and legacy. It also poses a question that is set to crop up again and again: what public stories involving famous people do we have the right to film? And under what conditions?

Moral rights

Pierre Bergé insists he has not sought to block Bonello's production. The film, produced by brothers Eric and Nicolas Altmayer and which was handed to Bonello in September 2011, was due to have a budget of around twelve million euros; but it will ultimately be made with less. As a result the director has recently spent several days tightening the narrative, following the principle of French film director Jean-Luc Godard: “Tell me how much money I have and I'll tell you what film I can make.”

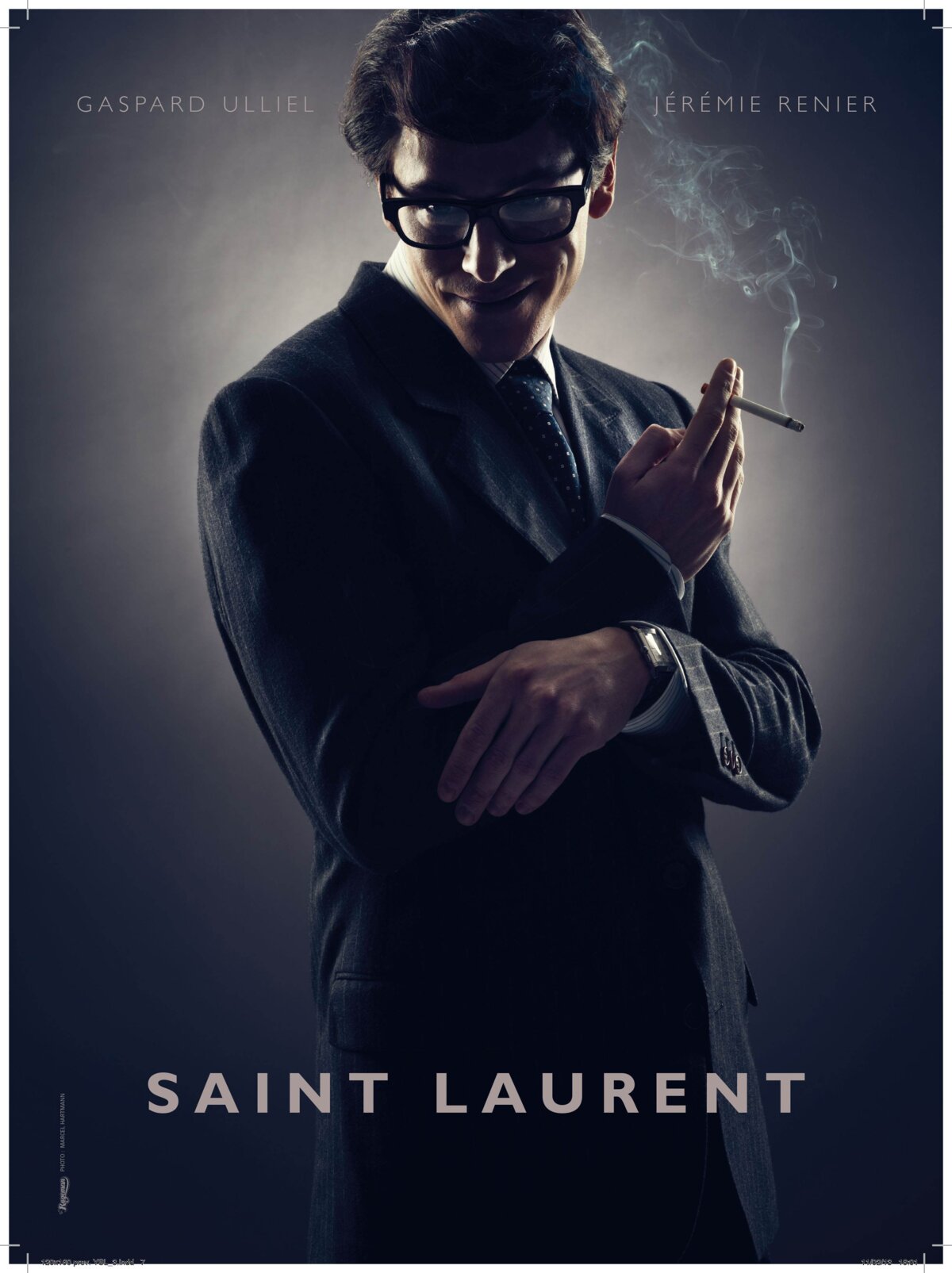

Enlargement : Illustration 1

Filming of Saint Laurent was supposed to have started this June. Instead, and after the project came close to being scrapped altogether, it will now start on 30th September. The executives in charge of films at Canal+ - which backs many French film productions - had initially come down in favour of Bonello's movie over the rival one on Yves Saint Laurent. But in the end the TV station will financially support both of them. Why the change in direction? Quite simply because Yannick Bolloré, son of the billionaire French businessman Vincent Bolloré, who is the principal shareholder in Canal + owners Vivendi, has become the majority partner – with 97% of the shares – of producer Wassim Beji at WY Productions. They are the producers of Lespert's film.

During the Berlin Film Festival in February, when both film productions were presented to international buyers, Beji told the film industry magazine Screen International that Bertrand Bonello would not have permission to use Yves Saint Laurent's clothes collections. As a result he compared the film to La Môme (La Vie en Rose in the English-speaking world), the movie about singer Édith Piaf, which did not use all of Piaf's own versions of her songs. In his Le Petit Journal interview, Pierre Bergé also hinted as much.

However, these comments blur over the facts. For neither Bonello nor Lespert need the permission of Bergé to use the clothes. The originals are conserved in trunks and there is no real question of getting them out. As for the rights to reproduce them, that is down to the permission of the luxury brands company PPR (now known as Kering), who own the Saint Laurent Paris brand, and not Bergé. The boss of Kering, François-Henri Pinault, has given his permission to Bonello. Bergé has thus uttered a half-truth which, because of his link with Saint Laurent, his fame and his fortune, has quickly become accepted as fact.

When contacted by Mediapart, Bergé's lawyer Emmanuel Pierrat pointed out that his client is the “legatee, legal holder of the moral rights of Yves Saint Laurent's work” and that these rights are “the most important rights that exist for a designer's work, which easily take precedence over brand rights, property law. It's the right in respect of the name, the right in respect of the man.” This seems undeniable. However, while such rights may give rise to legal action once the film is completed, they in no way authorise attempts to stop it from existing from the start.

Yet that is what, in effect, has happened: Bergé has tried to stop the Bonello film from getting off the ground. And he was close to succeeding. Indeed, when Mediapart first spoke with Bergé's lawyer Emmanuel Pierrat at the beginning of May after it had been announced that the Bonello film would not be filmed in June, the lawyer said: “For the moment I've put the case to one side. When a movie's filming gets postponed there's a chance the film won't get made. At the moment cinema funding in France is a difficult thing...”

The makers of the rival film have not made life easy for the Bonello production, either. Lespert and Beji have sought to sign up several actors who had already been approached by Bonello for his movie; for example they announced, without informing her, that Léa Seydoux would be in their film. In fact she will play model and fashion muse Loulou de la Falaise in Bonello's version. It is even rumoured that, despite having only having started filming this June, they would be ready to compete in this year's Venice Film Festival just three months later. In fact, there is no need for Lespert's film crew to rush now; given that their rivals will not be filming until September they are sure to come out first. WY Productions did not reply to Mediapart's questions on this. Pierre Bergé's office said that he had spoken enough on the subject.

'Climate of terror'

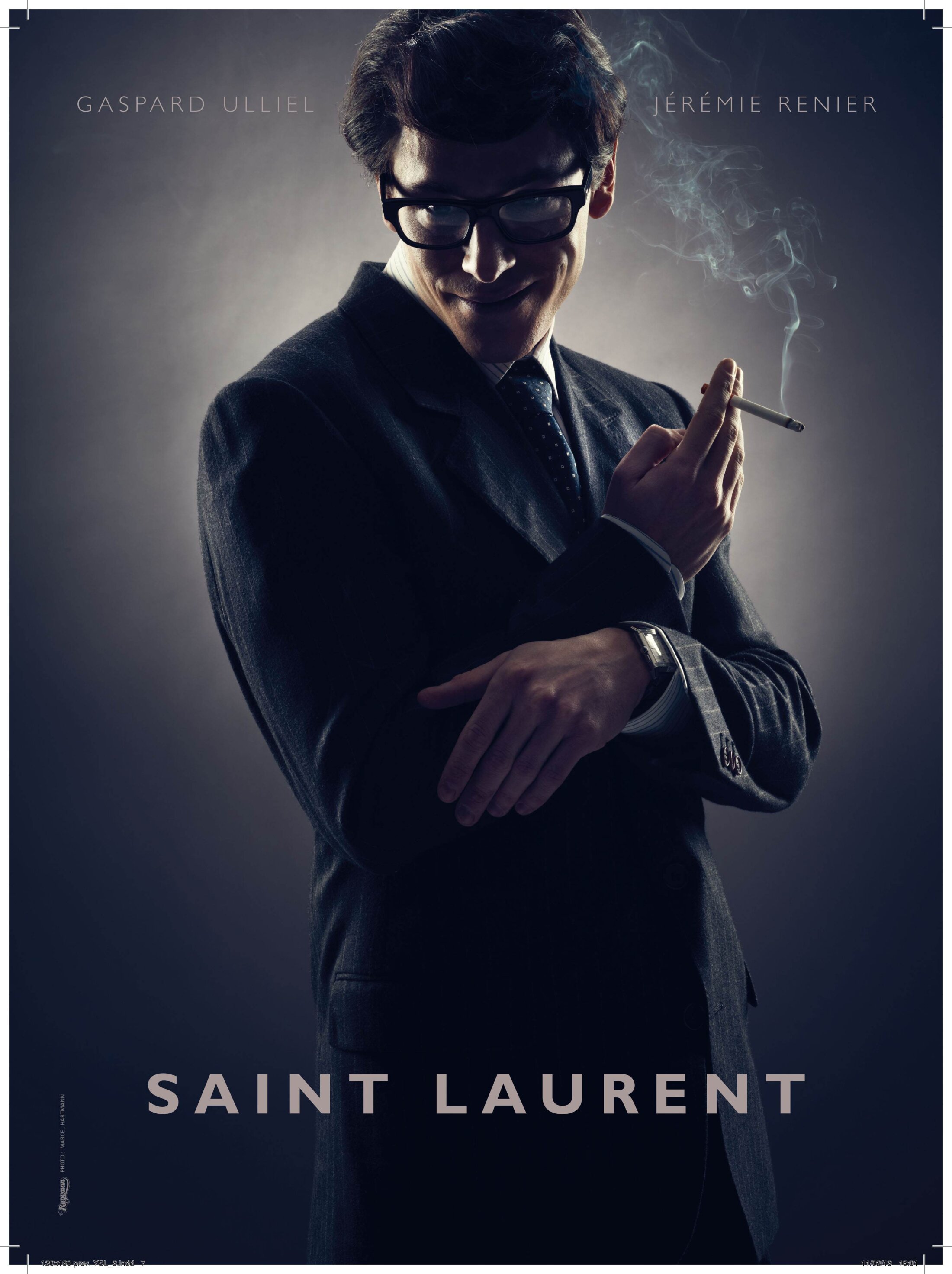

Enlargement : Illustration 2

Bonello believes that Bergé has managed to create a “climate of terror” around his film. Whether that was his intention or not, the businessman has certainly taken a firm stance over legal issues relating to the movie. For example, there was a Tweet from Bergé on 18th January which some consider contained a veiled legal threat: “2 films on YSL? I hold the moral rights in YSL's work, his image and mine and I have only authorised Jalil Lespert. A court case on the horizon?” Hugues Charbonneau, producer at the production company Films de Pierre – Pierre as in Pierre Bergé – has also Tweeted on the matter, writing early in February about a “question of respect”.

There was also a barrage of letters sent by lawyer Emmanuel Pierrat to all the people contacted by Bonello and producers Mandarin Cinéma in relation to their film: distributors, television stations, film investment structures known as SOFICAs, broadcasters and financiers.

These letters stated: “In this matter, Monsieur Pierre Bergé will not tolerate any interference in the sphere of his private life and the use of his image, of whatever nature. Moreover, in his capacity as holder of the moral rights relative to the entire works of Yves Saint Laurent, Monsieur Pierre Bergé is particularly interested in keeping watch with regard to the integrity and the quality of the work of the artist, in line with the measures in L.121.1 and subsequent articles of the [French] Code on intellectual property.”

The letters continue: “As a result, all reproduction, use, broadcast of Yves Saint Laurent's designs on whatever media support must necessarily obtain the assent of Monsieur Pierre Bergé. This prior authorisation is imperative for all of the artist's designs and covers notably the clothes but also the paintings, drawings, sketches, shows, writings of all natures, press interviews and television appearances.

“Failing this, any such use of the original Yves Saint Laurent works themselves or possible imitations in constructing a scene would be characterised as acts of infringement of rights and would give rise to legal proceedings.”

This could all be simply be sensible caution on the part of the businessman and his lawyer. After all, it is Pierre Bergé's life that is at issue here. It seems, though, that the mere mention of his name was enough to dissuade several potential parters from signing up to the project. Not because they thought they would be in the wrong, but to protect themselves against any possible reprisal.

Kissing the oriental slipper

It is hard to understand such hostility, even more so as the nature of the two films themselves has seemingly played no role in Bergé's view of them. Indeed, Berge's tough stance over Bonello's film seems to go against his own aesthetic leanings: he is attacking a project that is clearly closer to his own world. He grudgingly recognised this in the Canal + interview. In private he has apparently even expressed a leaning towards the “underground” nature of Bonello's film.

In fact, it is easy to see why Mandarin Cinéma gave the project to Bonello. With its lushness, its tale of twelve women trapped inside a 1900s brothel and its painting-like settings, his film L'Apollonide – known in English as the House of Tolerance - is the depiction of a form of parade, set against the backdrop of a bygone era. Here, already, was incarceration inside a kingdom of beauty. In his directing Bonello drew on the work of German expressionist filmmaker Paul Leni and Italian director Luchino Visconti but also the writer Marcel Proust, who was a powerful influence on Saint Laurent, to the point that he often travelled under the pseudonym Swann – a reference to 'Swann's Way', the first volume in the author's seven-volume Remembrance of Things Past. The designer also named bedrooms at his home in Normandy in north-west France after characters from the novel.

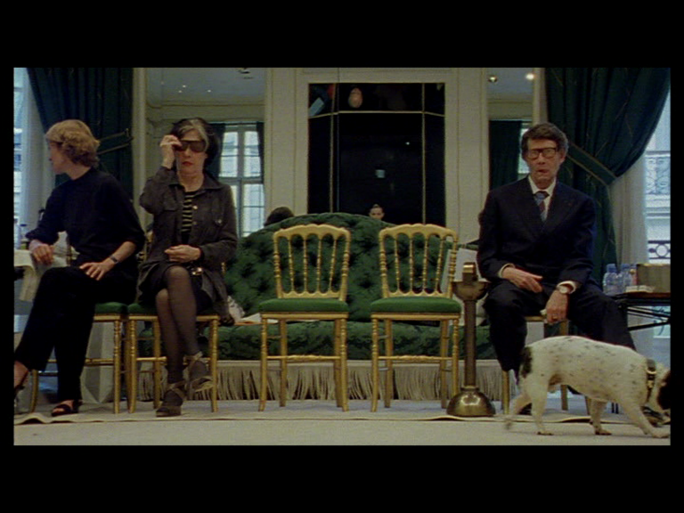

Enlargement : Illustration 3

Jalil Lespert is an entirely different proposition. He is noted as a marvellous actor, especially in the films Ressources humaines (Human Resources) and Le Petit Lieutenant (The Young Lieutenant) and has directed two full-length films, 24 mesures (24 Measures) and Des vents contraires (Headwinds). Some consider these works of no great significance, and they are certainly far removed from the imaginative world of Saint Laurent. It's hard to see the connection; apparently, even for Bergé too.

Bergé's views of the films do not seem, either, to depend much on the stories they actually recount. Certainly some of Lespert's film is narrated by Bergé's character; at the auction of the Saint Laurent collection that he organised at the Grand-Palais in Paris in 2009, Bergé retraced the steps of his life, as happens in biopic movies. It's true, too, that Bonello's film, which covers the years 1967 to 1976, opens with the arrival of the designer at the Sofitel Hotel at Porte-Maillot in Paris where he books a room under the name of Swann. From here he calls the press for an interview – whose publication Bergé immediately wants banned – in which he says he is prepared to tell all about his stay at a French military hospital in Paris where he was sent soon after being conscripted into the French Army in 1960 to fight in the Algerian War of Independence. In the hospital he was given sedatives and electroshock therapy. So it would seem that Bergé's character is given more benign treatment in Lespert's film. However, that seems not to be the cause of the problem either.

This is for at least two reasons. For one thing, Bergé had no knowledge of Bonello's script. For another, Bergé had little to fear from whatever revelations the film might contain, for he has always publicised his relationship with the great designer, including its more inflammatory aspects, most notably in the posthumous letters that he published in the book Lettres à Yves (Letters to Yves) published in 2010 and in the 2010 documentary L'Amour fou (Mad Love) directed by Pierre Thorreton and produced by Les Films de Pierre.

In fact, the real reason for Bergé's anger towards Bonello's film is both simpler and more absurd. Bergé had no hesitation in giving it during his interview on Le Petit Journal: “As he didn't ask me for anything, it doesn't interest me.” In other words, it is all about respect for position and hierarchy. In the world of films and fashion there is a particular expression for visits made expressly to seek someone's approval, and without which, it seems, nothing is possible. It is called “going to kiss the feet” (1).

Lespert did kiss feet. That is why he has the support of Bergé who in January organised a cocktail reception in honour of that film's international distributors. At this gathering actor Pierre Niney welcomed the guests dressed and made up as Saint Laurent, causing Bergé to tweet: “Yesterday, at YSL's, with Pierre Niney who will be Yves in Jalil Lespert's film, disconcerted by the resemblance I almost said Welcome Yves.”

Bonello and Mandarin did not kiss feet. They stuck to their “artistic integrity”. One can understand them. Was it not Bergé who produced and narrated L'Amour fou, a worthy but pious film that concludes with the delighted expression of the old man at the end of that incredible auction at the Grand-Palais? Had he not also, in Lettres à Yves, re-written posthumously the story of his life with the designer? And does he not have a long history of rages and threats?

-------------------------------------------

1. In the French the word used is 'barbouche' which is an oriental or Turkish slipper. The sense is of going to pay court to a potentate.

History repeating itself?

One of the most puzzling aspects of this current affair is that there is a precedent to it. In 1998 Olivier Meyrou was signed up by Bergé to direct a documentary on the designer, called Célébration. Filming and then editing took place with no problems, up to the point where the distributors MK2 expressed an interest in distributing it. Meyrou then received word from Bergé that he reserved the right to take legal action the day the documentary was broadcast.

Bergé doubtless feared that this portrait of Saint Laurent, made at a time when the designer was exhausted and who gave the impression of being a survivor from the dying era of haute couture, was too gloomy. Except that, once again, the problem seems to have lain elsewhere. Meyrou was apparently the victim of Bergé's anger against the filmmaker's companion Christophe Girard, who had previously worked with Bergé until the two had a professional disagreement in 1999.

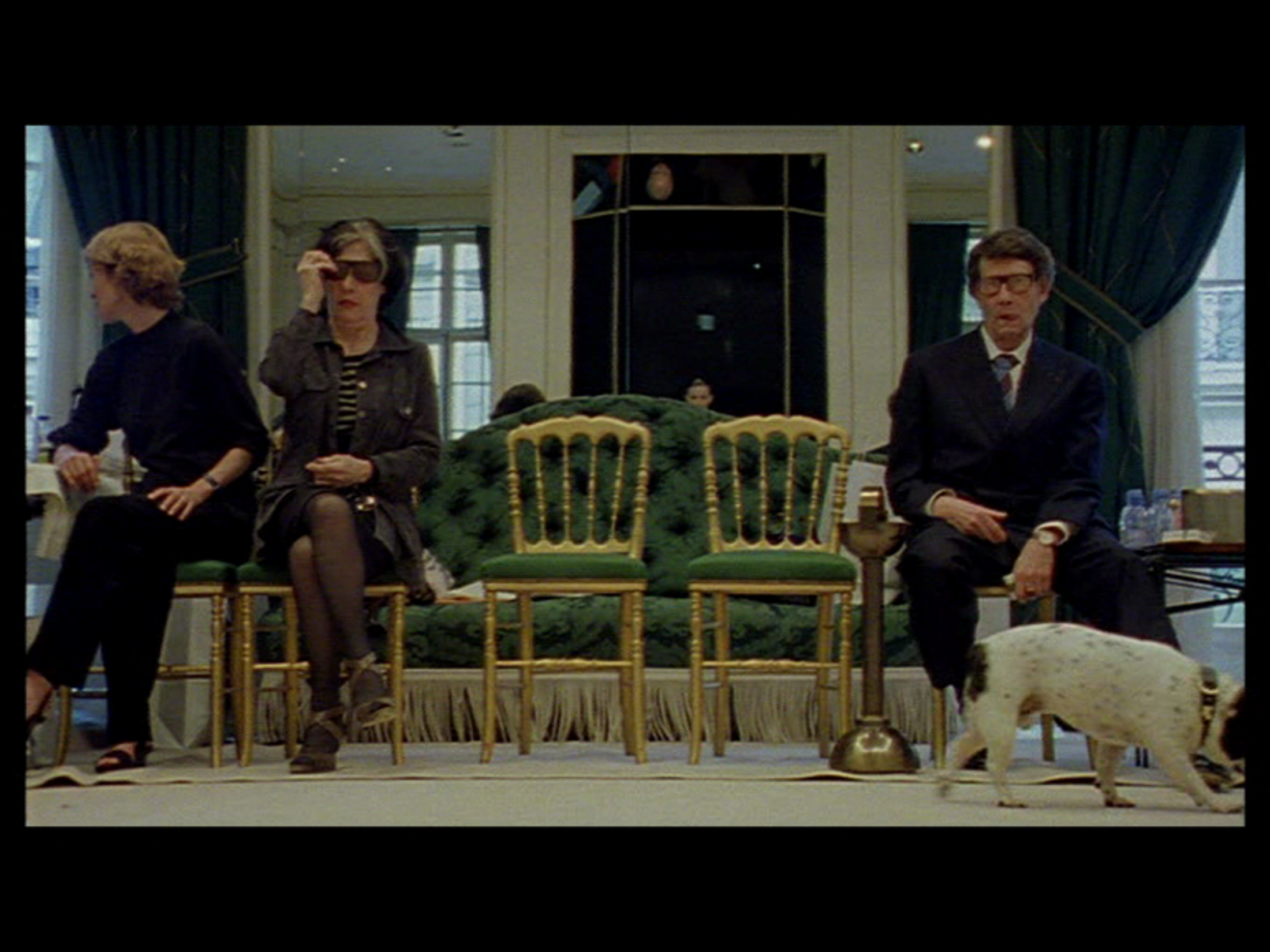

Enlargement : Illustration 4

Meyrou received a letter from lawyer Georges Kiejman warning him about Bergé's “power to support or be a hindrance over the long term”. In other words, about the businessman’s ability to make or break the career of someone who was at the time a very young filmmaker.

The result was that Célébration was screened at the 2007 Berlin Film Festival but never shown in cinemas. It has since been very difficult to see this beautiful film in which the designer comes across as a hunted animal, a man so shy that even his assistants approached him on tiptoe. From that same period there remains just one other film – which is no less beautiful – made by David Teboul and called Yves Saint Laurent, 5, avenue Marceau, 75 116 Paris. This was the only film that Bergé said he had “authorised”, the expression also used by the businessman in his tweet in January this year about the current films. History is thus repeating itself almost exactly.

In Célébration there is a phrase that seems like an admission. Bergé recalls the certainty that he had in the middle of the 1960s that Saint Laurent was the greatest of the design houses. It was a hasty judgement, he makes clear, as at the time 'Coco' Chanel, founder of the brand that bears her name, was still alive. And he adds: “You have to live your assertions for them to become convictions and to enable you to share them with others.”

There is no doubt that the remark expresses a grandeur that is inseparable from the “insincerity” that Berge confided on Canal + was his greatest fault. It also betrays what, according to Oliver Meyrou, has always been the personality's fear: that history would not remember his name, particularly and above all alongside that of Saint Laurent. That fear would explain why he feels so strongly about being in charge of the narrative of the place that he will occupy in a history that is, clearly, catching up with him.

Meyrou refers to a “man who ceaselessly generates his own story-telling”. That's why the actual content of the narrative does not really matter. The only thing for Bergé is to be in charge of it. Meyrou wonders if there is not a wider problem at stake here: would it be possible today to make a film about prominent French businessmen and billionaires Bernard Arnaud or François Pinault without their authorisation? It is as if what matters are not the images themselves but the authority that allows – or stops – their publication. It is as if one no longer fights to control the story but instead its ownership.

------------------------------------

English version by Michael Streeter