They have fled bombardments, travelled thousands of kilometres, crossed dozens of state borders and risked their lives in crossing the Mediterranean sea. But the ordeal for this handful of Syrian families in Paris is still not over. They have set up a makeshift camp in squalid conditions close to the main ring road, the périphérique, in the north of the French capital. Tents, mattresses and blankets are laid out on a narrow strip of dusty ground next to a road that is regularly used by buses returning to their depot and which narrowly avoid the migrants' children as they pass. In one corner there lies a baby walker, in another some toy animals. Two little children are running around.

It's a Thursday afternoon and around ten men, aged between 20 and 30, are chatting as they lean against a little wall that runs along the side of the slip road leading to the main carriageway. A woman gives some biscuits to her daughter while another woman, who is pregnant, takes a rest in a fold-up chair. The camp first attracted attention two or three weeks ago and is temporary home to between 15 to 60 people at any one time, its residents coming and going depending on whether they can find the money for an hotel room. Or, in some cases, depending on whether they have left to continue their journey. French organisations who help migrants say it is the first time in a year they have seen Syrians sleeping in the streets, in Paris at least.

Enlargement : Illustration 2

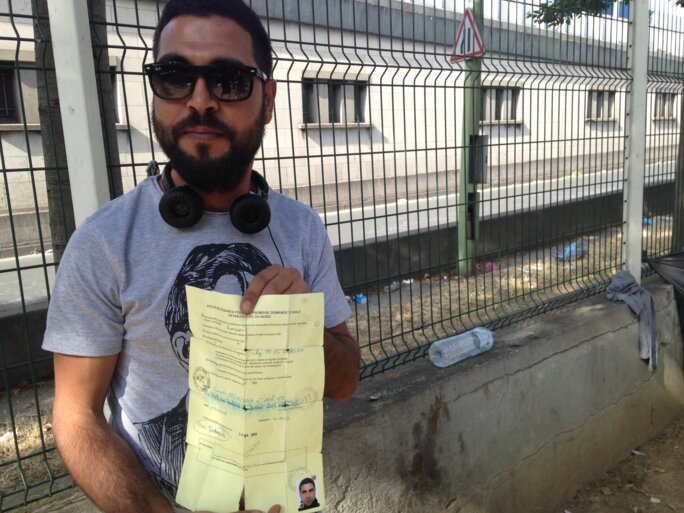

Standing apart from the others is Mustafa, 26, who removes his headphones and suggests that Mediapart listens to the music of the famous Syrian singer George Wassouf. The volume on his mobile phone is turned up to maximum but such is the noise of traffic on the périphérique that the music is almost inaudible. He then agrees to tell his story. “It's a real war back there, half of my family has been wiped out,” says Mustafa, surprised to be asked why he has left his home in Syria. “I was away one day. When I came back my father and brother were dead.”

Mustafa is from Latakia, Syria's main port city situated on the Mediterranean coast. “Syria is no more. The Syria that I knew no longer exists. What can you do?” he asks. He had never thought about leaving his homeland before civil war erupted in 2011 and speaks of his earlier life there as a distant but happy memory. “I was a painter and decorator. I had work, my family, my friends, a house, I lived well there. I had absolutely no wish to leave.”

However, the deaths of those close to him persuaded him it was time to go. He had a vague plan to go to Belgium, a country he had heard about through word-of-mouth in the district where he lived in Syria. After collecting his belongings and all the money he could lay his hands on, Mustafa set off to the Lebanese capital Beirut where he worked for several months, without ever planning to settle. “There were too many Syrians there, there was too much competition on the work sites,” he explains.

Using false Lebanese papers he headed for Tunis and then crossed Algeria by taxi. Having arrived at Melilla, a Spanish enclave on the Moroccan coast, all he needed to do was scale the town's high fences. A document bought from a Moroccan businessman gave him the right to enter the European Union. He survived this difficult journey unscathed and indeed, with his close-cropped beard and fake Ray-Bans in his hands, the young man is rather smart in appearance. “I'm single, it's easier” he explains.

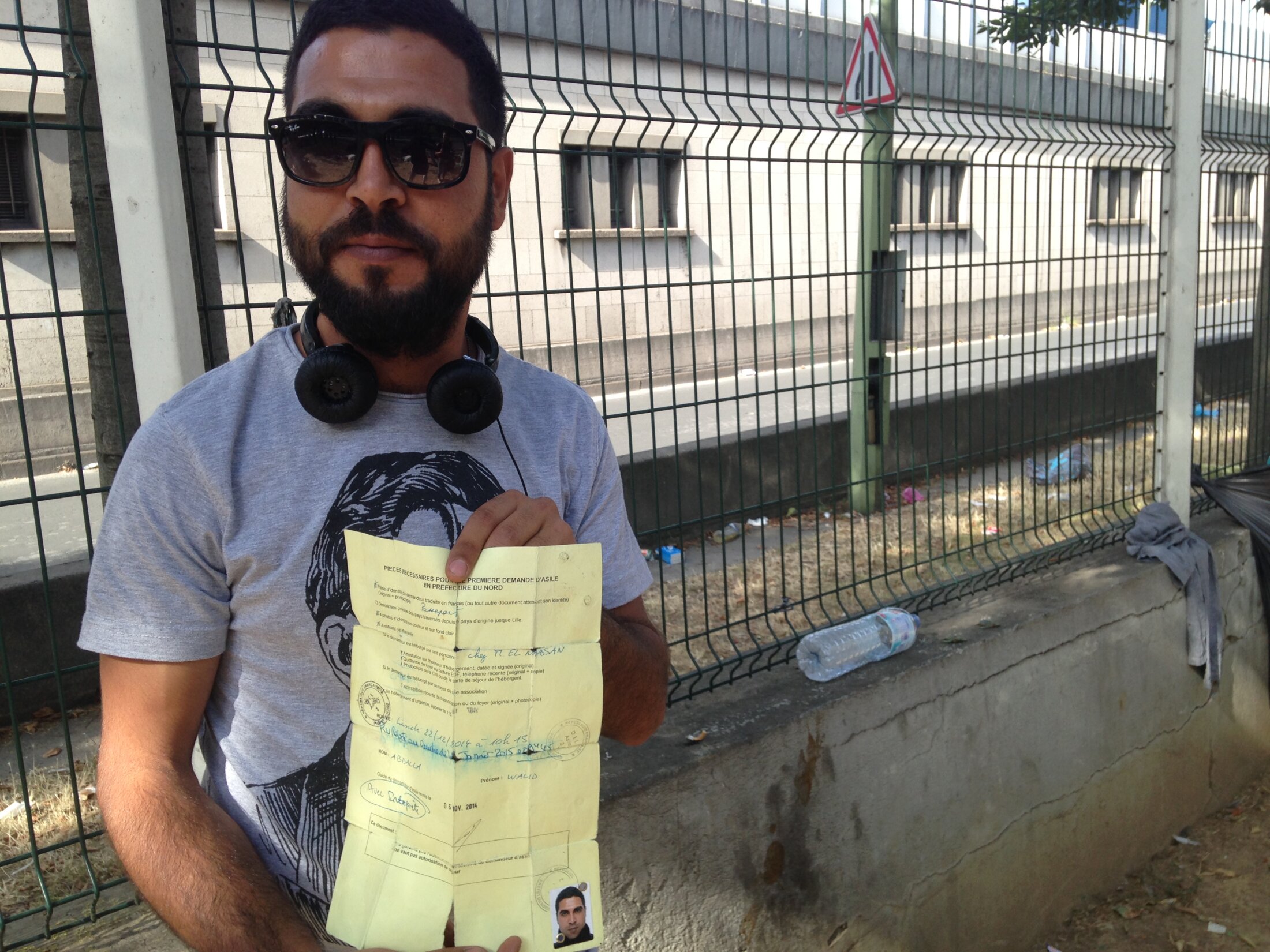

Once in Spain Mustafa took the train from Barcelona to Paris. That was a year ago. But his wandering has still not ended. A trip to Belgium left him unconvinced it was right for him. Back in France, he stopped off at Lille in the north of the country and began the process of applying for asylum. However, worried about the fact that he was met by the police at the prefecture when he made his application, and discouraged by the length of time the process was taking, he did not attend the meeting to which he was called several weeks later. It is hard to understand his reluctance to carry on with the administrative process because, as a Syrian, he has an almost 100% chance of obtaining refugee status in France. He says he was not aware of this.

Enlargement : Illustration 3

“There is something else,” he confides, as he folds and unfolds the yellowing price of paper on which the date of his missed meeting is written. “I deserted. If I am registered and they find me, I'm dead.” Fearing reprisals against his family back in Syria he says: “It's all pointless. What's more, they took my fingerprints in Spain. Is there a risk I'll be sent back there?” He is not wrong to be worried about being returned to Spain; under the so-called Dublin System member states send asylum seekers without the correct paperwork back to the first EU country that they entered (as long as there is evidence of that). So according to the law Mustafa could be “readmitted” to Spain, which is supposed to deal with his request for asylum. Despite his smile it is clear that Mustafa is lost: “I think about my mother all the time. I'm always worried about her and I don't have the means to save her,” he says despairingly. He communicates with her via WhatsApp. He shows his Facebook page and his list of 'friends' on it, and soon he is overcome by nostalgia. “I've had enough of it, I've lost all hope. I've nowhere to go,” he says.

Michel Morzière tries to reassure Mustafa. Morzière is the co-founder of of the association Revivre, one of the few to help Syrian refugees in the Paris region, and he offers to sort out his problems one by one. He is used to cases like this, where the situation is complicated by the fact that people come and go and hesitate about what to do. “These situations are not easy to grasp. You need time to understand them,” he says, criticising the public authorities for leaving him to deal with these initial steps on his own. Yet France is not deluged with asylum applications from Syrians, who generally favour Germany or Sweden where they have family and where accommodation is immediately available. Indeed, since the start of the 2011 crisis France has taken in just 6,000 or so Syrian refugees out of a worldwide total of four million, most of whom are now living in countries bordering Syria.

“Many Syrians who come to Saint-Ouen are just passing through,” says Michel Morzière. “They're artisans, trades people, who are not really looking to settle. They have contacts in several European countries and the Maghreb [editor's note, part of North Africa]. They avoid talking about politics and are wary of administrative procedures.” Some of those he has met have refused to hand over their passport to the French state in return for refugee status because they fear they will never get it back and will never see their family again.

'The public authorities hope that the camp will disappear by itself'

Ramadan, who has arrived with his wife, mother and three sisters via Turkey, Greece and Italy, also sees no way out of his predicament. But in his case it is for a different reason: the 20-year-old has lost his passport. His belongings were lost overboard when he and his family crossed the Mediterranean. “I went to the embassy in Paris but the door was closed. I want to ask for asylum but I can't!” he says. Not having a passport will certainly make the administrative procedure of applying for asylum much more difficult, especially given the lack of contact between France and the Syrian civil authorities.

Ramadan is worried but at least, unlike Mustafa, he has found accommodation. One room, to be precise, rented for 400 euros a month and shared between eight people. However, he visits the camp frequently to find solace among his compatriots who, like him, were told that Saint-Ouen was a meeting point on the road to exile.

Enlargement : Illustration 4

Ali, who is 27, has also found his way blocked. A gaunt-looking figure, he is clutching in his hands the document showing that he has applied for asylum. Everything is in order; he turned up at the appointments as asked. But the accommodation he was supposed to be entitled to has still not materialised. “They told me they'd call me. It's gone on for three months. And still no news,” he says impatiently. In the meantime he, his wife and their children sleep in a car parked nearby.

“It's unacceptable,” says Michel Morzière. “The asylum system is so dysfunctional that people give up. You'd think that the state did it on purpose,” adds Morzière. He suggests to the Syrian that he goes with him to the official organisation that deals with asylum seekers, the Coordination de l’Accueil des Familles Demandeurs d’Asile (CAFDA), in Paris's 20th arrondissement or district, in the hope of speeding the process up. Ali agrees and thanks him, but gives the impression of not believing him, as he if has vowed never to expect anything from anyone again.

Enlargement : Illustration 5

Isolated in this corner of Paris, the Syrians at Saint-Ouen face going through the entire summer without support. Nearby, drivers wind down their windows and insult them. No one at the camp reacts. The Syrians say that some people in the neighbourhood bring them water, bread and clothes. But there is no support network of the kind that has sprung up in the La Chapelle, Pajol and Éole areas of the 18th arrondissement where migrants from Eritrea and the Sudan have been living in camps.

In Saint-Ouen police officers pass by the Syrians but do not stop. They have received their orders and just count the refugees. “The public authorities do the least possible. They hope that the camp will disappear by itself,” says Michel Morzière. “They hope that the people will move on, vanish into nature.” At City Hall in Paris officials insist they have been made aware of the Syrians' presence in the street and that they have been offered “support” - something the migrants themselves deny. “These people are mobile, they come and go. We don't know much about their intentions,” adds an official.

Yet the authorities already have recent experience of such a situation. In April 2014 around 200 Syrians with a similar background found refuge a few hundred metres from the current makeshift camp. Faced with an urgent humanitarian problem the organisation that deals with refugee and asylum seeker' welfare, the État et l’Office Français de Protection des Réfugiés et Apatrides (OFPRA), provided a tailor-made solution by setting up a form of one-stop administrative centre. Instead of the refugees having to wait weeks for successive meetings, everything was arranged in a day. At the same time as the migrants in that camp were given official notification that they had applied for asylum, half of them were allocated a place in an accommodation centre. Some were lodged at Roanne in the Loire département or county in central eastern France, while others were housed at Chambéry in south-east France. The tents disappeared.

Then in July 2014 a new camp of around 150 people sprang up, all of them Syrians. “Neither the state nor the city intervened for fear that it would encourage others to come,” says Michel Morzière. After several weeks, and with no help forthcoming, the families left of their own accord, without further ado – and without asking for what they were entitled to.

----------------------------------------------------------------------

- The French version of this article can be found here.

English version by Michael Streeter