It is now 15 years since a ground-breaking accord was signed setting a timetable for self-determination for New Caledonia, the French Pacific Ocean territory with a population of just under 250,000. Importantly, the Noumea Accord recognised for the first time the wrongs of colonisation and the human and cultural identity of its inhabitants, the Kanaks.

The archipelago, sitting 17,000 km from France which annexed it on September 24th, 1853, "was not empty", says the accord which underlines: "Grande Terre and the islands were inhabited by men and women who were called Kanaks. They had developed their own civilisation with its traditions, languages and customs that regulated social and political life. Their culture and their imagination were expressed in diverse forms of creation."

This art and culture features in a rare exhibition, Kanak, l'art est une parole, running at Paris’s Quai Branly Museum until January 26th (see more details bottom of page 4). Its timing has a strong political significance as the Kanaks are due to embark on the final steps in the process of self-determination laid out in the Noumea Accord as of 2014, when one or several votes on independence will be organised, and those remaining governmental functions managed from metropolitan France will be transferred.

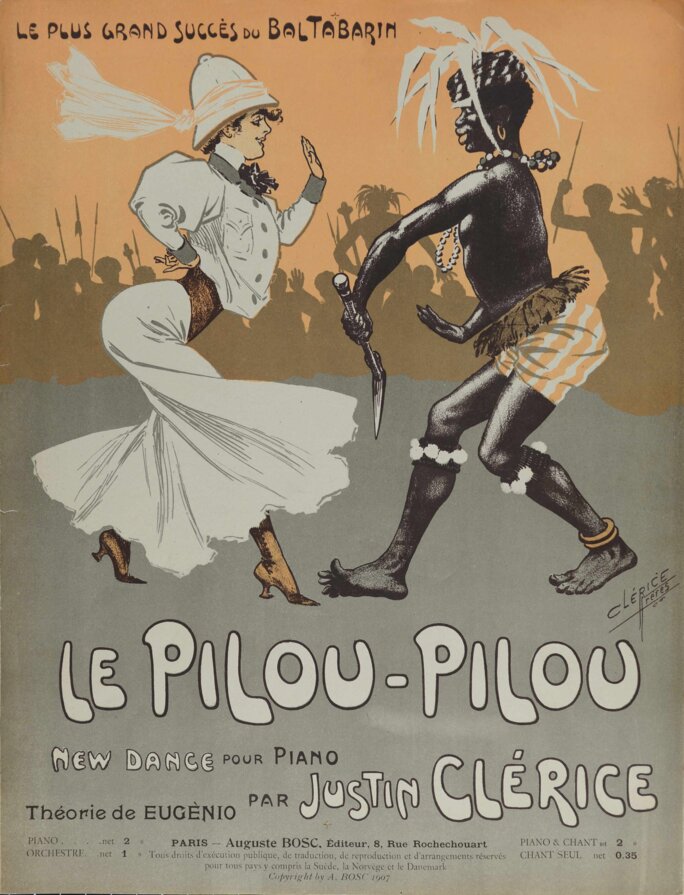

Enlargement : Illustration 1

Over the 1980s, separatist protests in New Caledonia brought the islands to the attention of the public in mainland France. These protests came to a head between the two rounds of the 1988 French presidential election with a hostage crisis in caves on Ouvea island, where the intervention by the French military left 21 people dead. Shock over the handling of the hostage crisis led to the so-called Matignon Agreements, which in turn paved the way for the 1998 Noumea Accord.

The exhibition now on at the Quai Branly museum, Kanak, l'art est une parole, (roughly translated as 'Art is a voice'), was put together by two heavyweights on things Kanak, Emmanuel Kasarhérou, former director of the Agency for the Development of Kanak Culture (ADCK), and ethnologist Roger Boulay. Their choices bring key aspects of Kanak culture and history to the forefront.

Firstly, instead of choosing to exhibit everyday objects, they picked high quality artefacts that demonstrate the universality of art, challenging notions of a Western monopoly on artistic expression. There are bamboos with delicate, detailed engravings, magnificently carved wooden doors, flèches faîtières, the carved spears or spires that adorn Kanak houses, and ostensorium axes, so-called because they resemble the monstrance, or ostensorium, used in Catholic rituals. These objects are singular works created by identifiable, recognised artists and artisans, contrary to the prejudice that such societies do not possess authors.

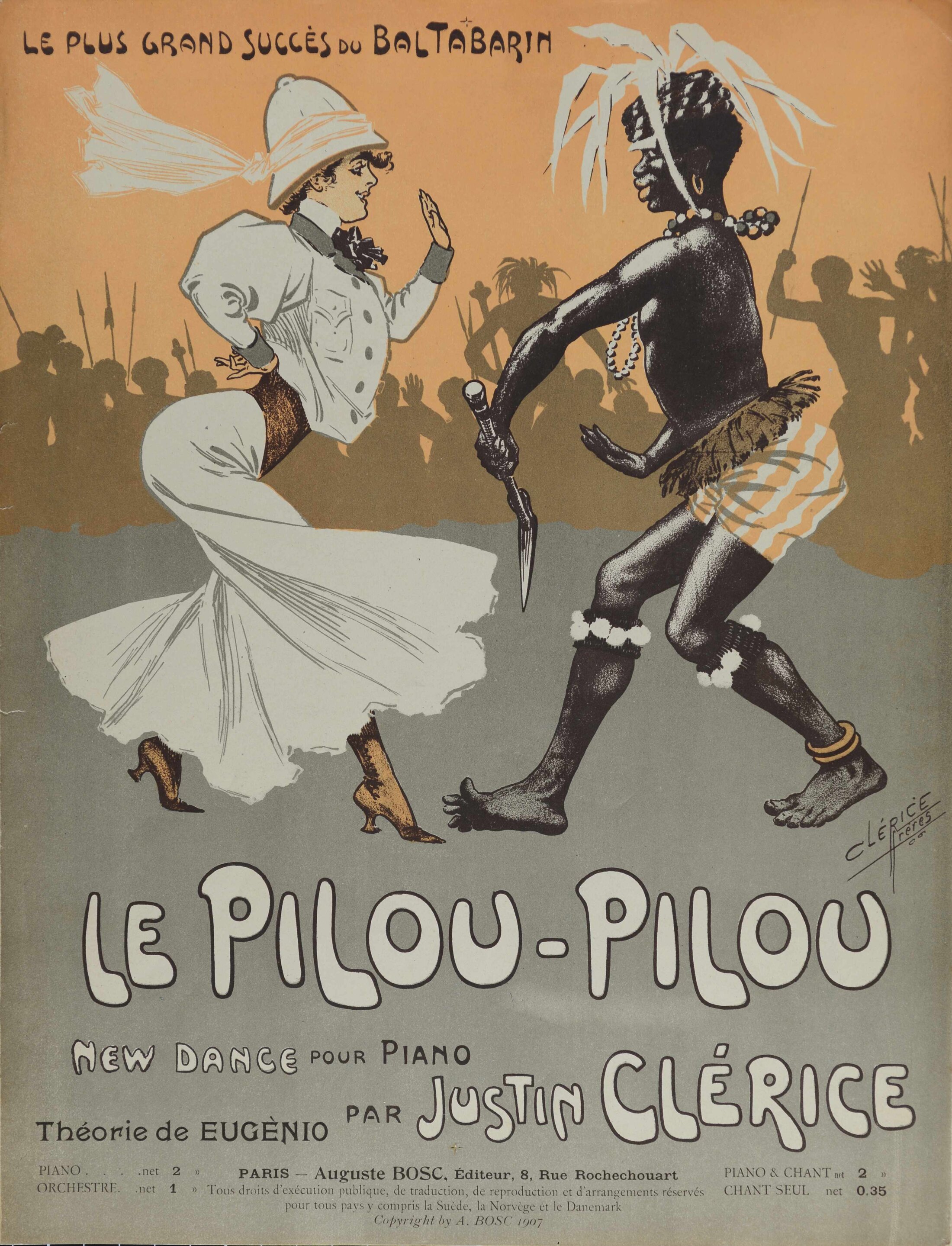

Enlargement : Illustration 2

Secondly, there is an emphasis on the importance of the word. This reflects the relative overdevelopment of oral traditions in societies that initially lacked writing, but also brings out the other meaning of the term "word" as a promise, an undertaking.

"The word, whether kept or not, has been a leitmotifof the Kanaks' struggle, " says anthropologist Alban Bensa, a Kanak specialist at the prestigious Paris social sciences institute EHESS.

This sensitivity was demonstrated in the reluctance of Kanak negotiators to allow the 1988 Matignon Agreements to remain purely a diplomatic text. They sought and obtained a referendum, which backed the road map to self-determination laid out in the agreements although participation was low.

Thirdly, and perhaps most importantly, the exhibition does not only show pre-colonial objects and the colonial period, but also brings the perception of Kanak culture right up to date with contemporary artefacts. This means that rather than portraying Kanak culture as intangible or fixed in time, Kanak identity is revealed as dynamic, powerful and open.

Tensions around traditions, modernity and missionaries

Stéphanie Wamytan, a young Kanak artist, offers her own interpretation of the so-called mission dresses that missionaries introduced to hide the nakedness of the "natives". Her version of the dresses is covered in erotic designs. Yet mission dresses – which, legend has it, were originally designed by the couturier Paul Poiret – have become an integral part of Kanak culture. Nowadays the wearing of mission dresses pits the older generation against young Kanak women, who prefer to wear shorts or trousers.

The exhibition is certainly a fitting homage to the vivacity of Kanak culture. But, as in the example of the mission dress, it incites questioning of what constitutes Kanak identity rather than professing a single identity.

Kanak society offers plenty of similar examples, such as the impact missionaries had on Kanak marriage customs. "As far as we know, before colonisation, the marriage ceremony was not very important […] It was missionaries who came at the end of the 19th century, from a rural France that was already worried about maintaining its traditions, who would impose a much more significant marriage ritual on the Kanaks, " said Bensa, the anthropologist.

From involving only small exchanges of money and food, marriage ceremonies then became a much bigger event, lasting for up to two weeks, with many speeches and the exchange of very large gifts, he said. "What is presented as the custom was in reality reformatted by missionaries."

The way the exhibition presents Kanak culture echoes the concept Jean-Marie Tjibaou, a renowned Kanak independence leader, advocated for understanding Kanak identity: looking ahead rather than clinging to established traditions or dwelling upon the impact and suffering of the colonial period.

The colonial period is of course represented at the exhibition. It includes a particularly moving short film on the role of Kanaks in World War I, showing how 1,400 were sent to the battlefields of Europe and 400 died there. Yet their names were not carved on war monuments until the mid-1980s.

The dynamic image the exhibition gives of Kanak culture has particular political relevance right now, Bensa says, as some Kanaks in New Caledonia are withdrawing into external markers of identity. "They are not the majority but they are influential, and they have just published a 'Basis for Kanak Values', which is hardly compatible with the idea of an identity that is in constant evolution, nor with the idea of a common destiny, " he said.

Bensa added that there is palpable tension over what constitutes Kanak identity between some of the older generation, who are often unelected, and new generations "who are more taken up with finding a job". This is particularly so at a time when many people are experiencing economic difficulties and the benefits of nickel mining are unequally distributed.

There are also divisions between men and women. Traditional ‘coutumier’ judges have a recognised role under the ‘coutumier’ – or customary - legal statutes that cover New Caledonia’s Kanaks on anything to do with traditions and customs, particularly family and inheritance matters. But many Kanak women, particularly those who benefited from laws on parity of the sexes and now serve on municipal councils, are unhappy that ‘coutumier’ law could get a wider remit, as it does not recognise equal inheritance rights, for example.

The upcoming referendums on independence and self-determination will be testing the idea of a common Kanak destiny, enshrined in the Noumea Accord between Kanaks and Europeans living in New Caledonia. There is no knowing what the outcome might be, since even the questions to be put in the referendums have not yet been decided.

Much has changed since the Matignon Agreements 25 years ago, and the political context in the archipelago has never been straightforward. Bensa notes that some young Kanaks are not necessarily in favour of independence since they did not live through the troubled 1980s and grew up in Noumea, or had training and education linked to the territory's ties with France.

Some Europeans, he adds, consider that as Northern Province has done well out of its nickel mines, independence could allow them to enjoy the benefits of nickel mining without paying a tithe to France. However, France’s role has already been waning, illustrated by how Northern Province has forged agreements directly with China, the top customer for its nickel.

Bensa agreed to be Mediapart’s guide for a six-step visit, mapped over the following pages, to this remarkable exhibition, which does far more than simply portray Kanak history. It also provides a clearer perspective on the potential destiny of an archipelago that may even no longer after the impending referendums bear the name New Caledonia – the name the British explorer James Cook gave it when he ‘discovered’ it in 1774.

Anthropologist Alban Bensa commentates the exhibition 'Kanak. L'art est une parole'

Enlargement : Illustration 3

Alban Bensa on the exhibits of flèches faîtières (click above for audio, in French only):

“These are sculptures that adorned the top of huts and which were made by sculptors whose names we know well, whose clan names were well identified, and which were of course taken by the missionaries, sometimes given to missionaries, as a sign of allegiance the flèches faîtières were the political glory of the Kanak villages […]” Bensa explains that the artwork of these carvings is recognised as the work of named individuals, who the population recognise and remember. “The ancient Kanak societies were not authorless societies but quite the opposite, very, very individualized […] each person has his own things to tell.” The European-made cloth in the middle of the room is an example of what the missionaries brought with them and which they often used as extra covering for Kanak girls and women who they judged insufficiently and immodestly dressed.

Enlargement : Illustration 5

Alban Bensa on a series of photos of Kanak chiefs (click above for audio, in French only):

“These are posed-for photos, a little traditionalised, from around 1880.” Here, chief Mindia is wearing a skirt of cloth given by missionaries, instead of the traditional loin cloth because “they mustn’t be shown naked, they had to be a little ‘folklorised’”. Post cards, explains Bens, “were a huge market, used notably by missionaries to make money [...] they had their own services to make and sell them.” From around 1870, the French colonial authorities gave a number of Kanak chiefs, notably those recognised as triumphant warriors, titles such as ‘The Big Chief’ and special powers by to levy taxes and police their regions, acting as a relay to the colonial administration. Bensa explains that later, as other photos in this part of the exhibition show, they were given French-style military uniforms and medals. “This situation has endured up until today, because these administrative chiefs still exist,” says Bensa. When the Kanak population became French citizens after World War II “the first thing the population did was to no longer recognise the authority of these chiefs, who became a little like junk chiefs.”

Enlargement : Illustration 7

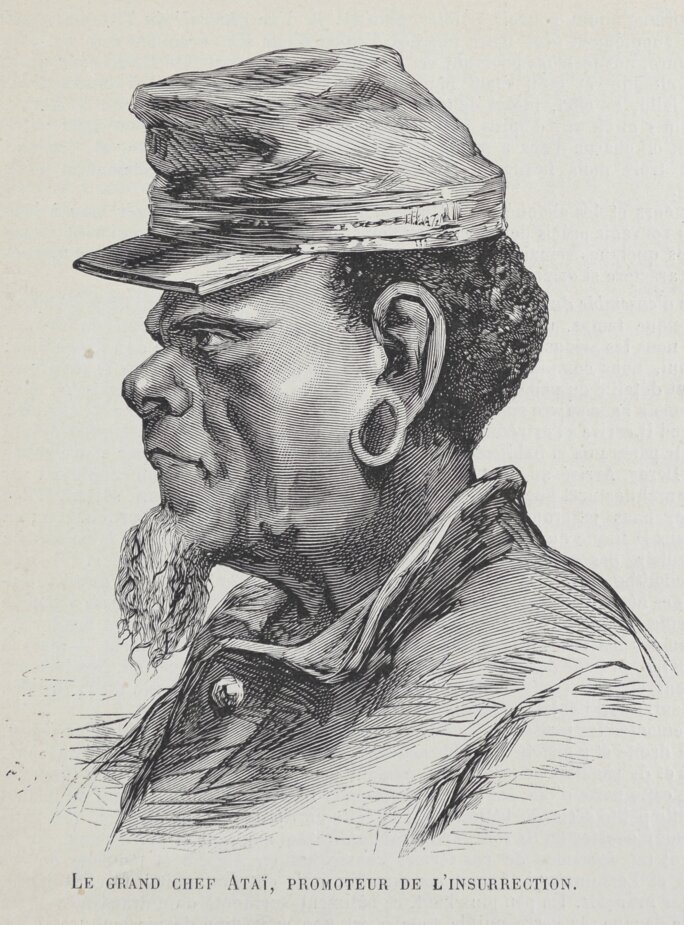

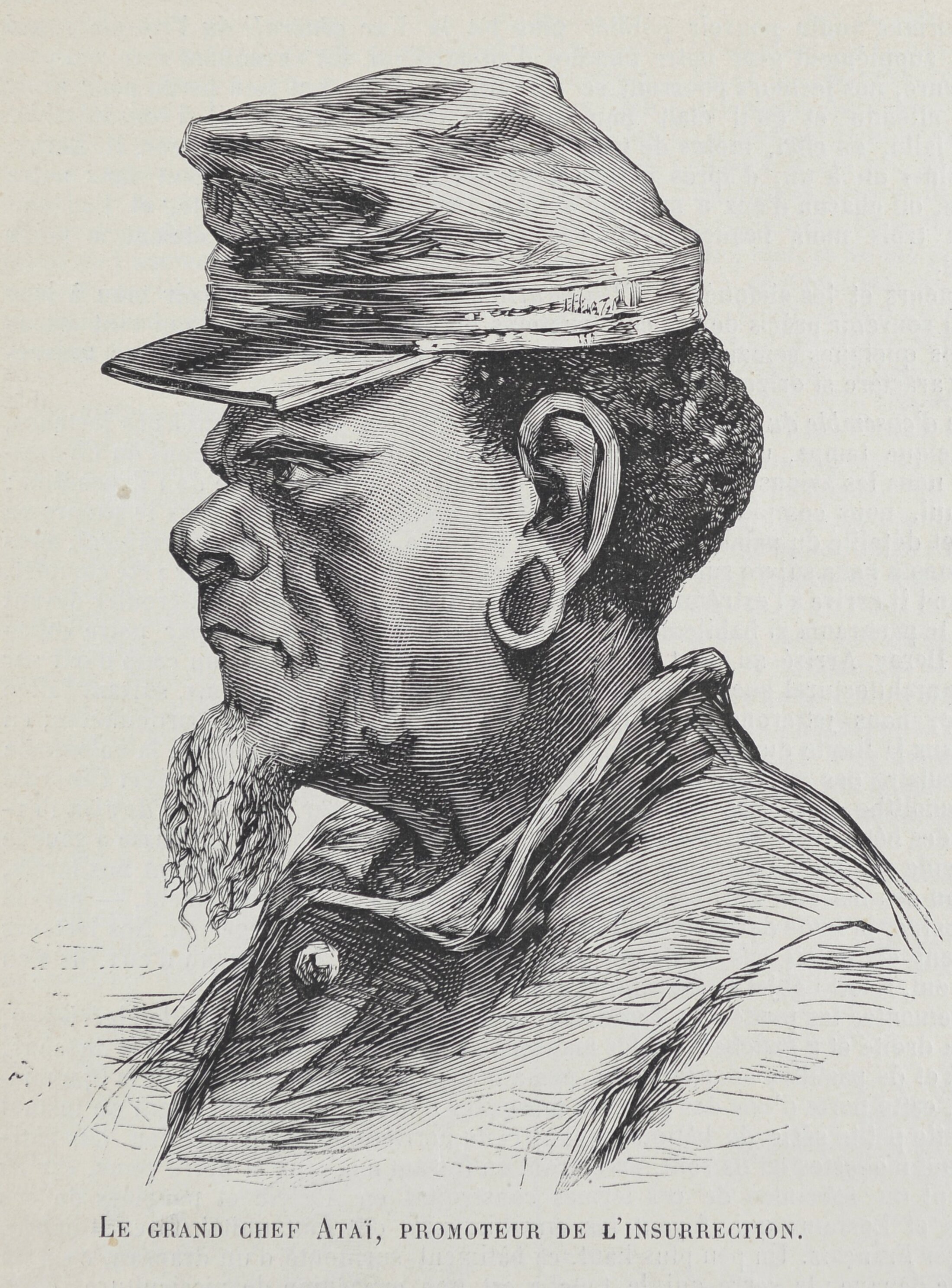

Alban Bensa on a drawing of Chief Ataï, leader of a major Kanak rebellion against the French colonial power (click above for audio, in French only):

"Chief Ataî launched the great insurrection of 1878, in the south-west of New Caledonia. It took France a while to put it down, and it succeeded with Kanak enemies of Ataï, playing on internal divisions.” After the earlier slaying of a French officer in charge of suppressing the rebellion – and who had underestimated the military strength of the Kanaks - Ataï and his magician were subsequently killed and their heads were sent to the Paris anthropological society. “The representation of Ataï is interesting, because it’s a European who did it for the armed forces. He popularised this image, with his cap and so on, without us having any other image of Ataï - there’s no photo. So this image imposed itself, a sort of symbol of the revolt, of the resistance.” When the Kanak nationalist movement gained momentum in the 1960s, this same image of Ataï was adopted by them. “What was a colonial image became an image used by the colonised to claim their Kanak identity,” explains Bensa. Two years ago a cast of Ataï’s bust was discovered at the Paris anthropological society. “If it is his real head, as is believed, it means we have something of his real face which has little to do with the image we have know for so long,” adds Bensa.

Anthropologist Alban Bensa commentates the exhibition 'Kanak. L'art est une parole'

Enlargement : Illustration 9

Alban Bensa on the 'Pilou-pilou new dance' (click above for audio, in French only):

At the end of the 19th century, the traditions of French colonial territories were caricaturised –“tainted by racism, it must be recognised” says Bensa - in music and on stage, notably cabarets, in mainland France. Pilou-pilou means “to dance” in Kanak, and the spectacular choreography of such dances were staged in a folkloric manner which, says Bensa, illustrated them as naked savages and cannibals. “This constructed an imagery that you find in Tintin, in the Red Sea Sharks, where among the insults that Captain Haddock shouts at the savages [...] is ‘Kanak’,” he observes, adding that the negative connotations of an undeveloped people continue to stick to the name in France today. “For people who manage the world’s second-largest nickel extraction plant it’s a bit annoying to be relentlessly referred back to this very colonial imagery and which France has a lot of difficulty in shrugging off,” concludes Bensa.

Enlargement : Illustration 11

Alban Bensa on Kanak 'currency' (click above for audio, in French only):

“What is called Kanak currency is not really money in fact,” says Bensa. “These are precious objects, which are exchanged between groups to demonstrate a strong relationship […] for marriages, or when someone has died to excuse oneself for not having succeeded in keeping them alive, to purchase a pirogue, for someone chased away to be welcomed into a tribe, to be leant a piece of land and so on.” When these precious objects are given, the custom is for the receiver to give another in return. “Sometimes they are kept in a sacred basket, and become a sort of treasure for a clan.” These objects which are often artworks are made from sea shells, and the one featured here contains mother-of-pearl, along with pleated hair from bats. They are still used today in marriage ceremonies and funerals. Bensa cites the case of a Canadian mining company which, when completing the signature of an agreement to build a nickel-processing plant in Koniambo, in northern New Caledonia, exchanged just such precious pieces with the tribe that owned the land. "I don't how the Canadians found the currency!" joked Bensa. The objects are symbolic of a person’s word and intentions. “They are linked to the person, and it is the trace of an agreement,” says Bensa.

Enlargement : Illustration 13

Alban Bensa on the Kanak national flag (click above for audio, in French only):

“The Kanak flag appeared in the 1980s, exactly when we don’t know », explains Bensa. It emerged along with the nationalist movement, as a necessary reference to prepare for independence. There’s no country without a flag, there’s no flag without a country […] the green stands for nature, the red is blood […] the Kanak idea is that the maternal uncles transmit the flesh and the blood […] by marriage the blood circulates from one clan to another, the clan being patrilineal. The blue is the sea. They added the symbol of ancient Kanak political authority which is the flèches faîtières, inside a sun.” During the discussions of the Noumea Accord, a national anthem was agreed but not a new name for the territory or a national flag. Concerning the latter, the Kanaks are against the proposition by the European population that the French tricolour be represented. “The debate is still ongoing, for the moment the two flags are there,” comments Bensa. “Will things stay like that? Maybe, perhaps that’s a solution. But it marks out the adherences of two communities which wasn’t exactly in the spirit of what was set out, which is that of a common destiny.”

- The exhibition 'Kanak, l'art est une parole' is on now and runs until January 26th 2014 at the Quai Branly Museum in Paris. Address: 37, quai Branly, 75007 Paris. Open from 11 a.m. to 7 p.m. Tuesday, Wednesday and Friday, and from 11 a.m. to 9 p.m. Thursday, Friday and Saturday. More details available here.

-------------------------

English version by Sue Landau and Graham Tearse

(Editing by Graham Tearse)